Search Results for 'older'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

August 21, 2024 at 12:27 pm #7546

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Potters of Darley Bridge

Rebecca Knowles 1745-1823, my 5x great grandmother, married Charles Marshall 1742-1819, the churchwarden of Elton, in Darley, Derbyshire, in 1767. Rebecca was born in Darley in 1745, the youngest child of Roger Knowles 1695-1784, and Martha Potter 1702?-1772.

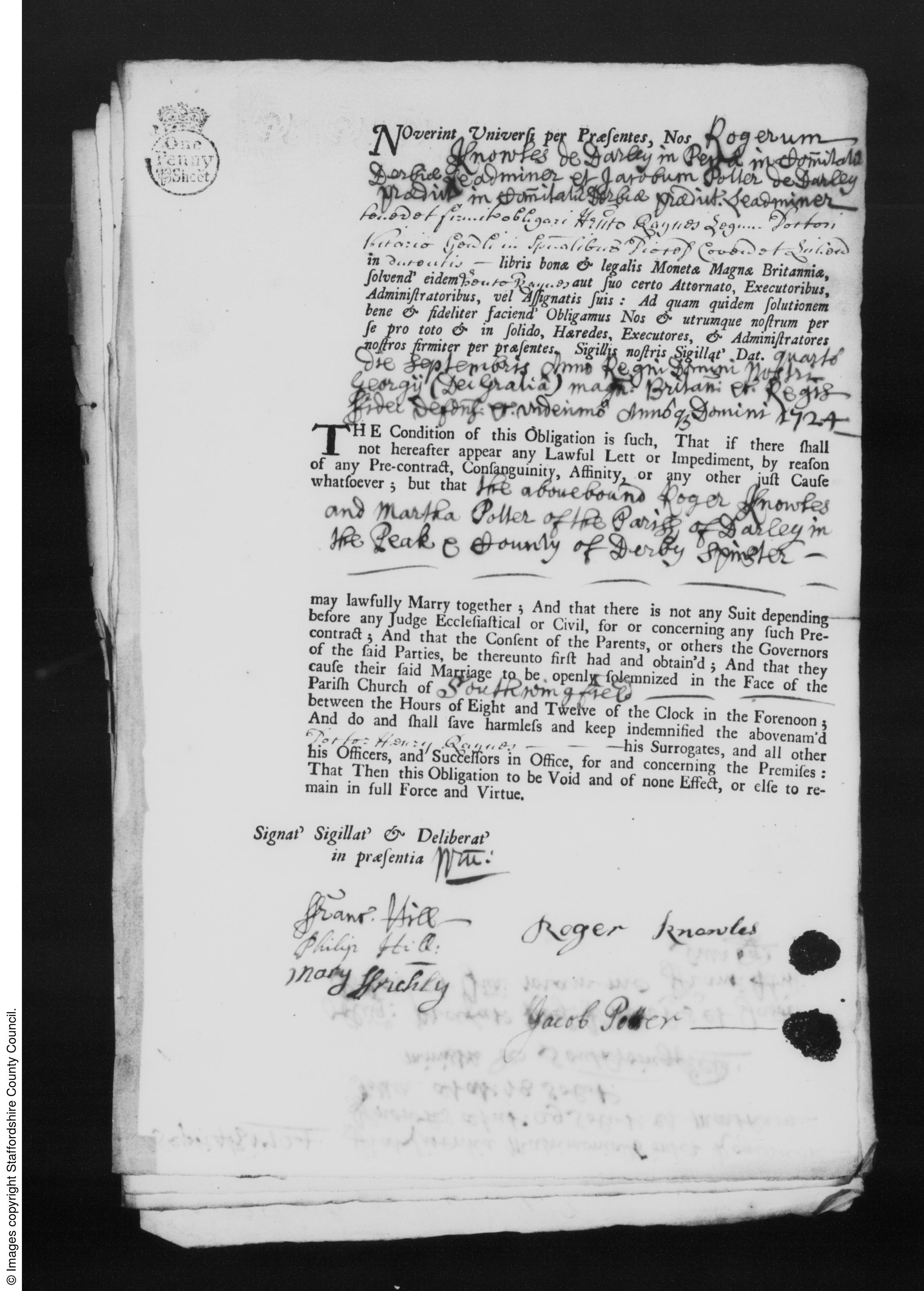

Although Roger and Martha were both from Darley, they were married in South Wingfield by licence in 1724. Roger’s occupation on the marriage licence was lead miner. (Lead miners in Derbyshire at that time usually mined their own land.) Jacob Potter signed the licence so I assumed that Jacob Potter was her father.

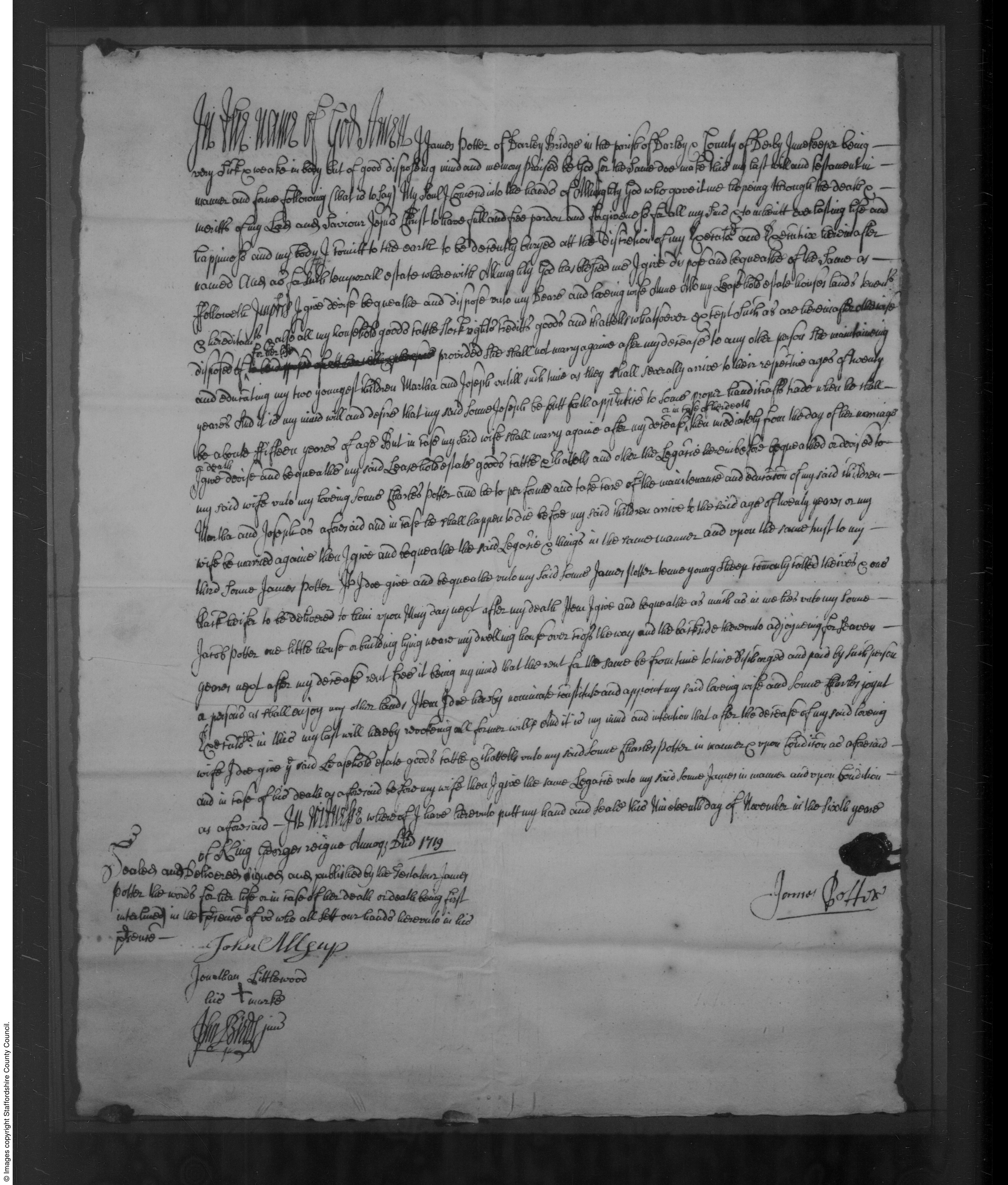

I then found the will of Jacobi Potter who died in 1719. However, he signed the will James Potter. Jacobi is latin for James. James Potter mentioned his daughter Martha in his will “when she comes of age”. Martha was the youngest child of James. James also mentioned in his will son James AND son Jacob, so there were both James’s and Jacob’s in the family, although at times in the documents James is written as Jacobi!

Jacob Potter who signed Martha’s marriage licence was her brother Jacob.

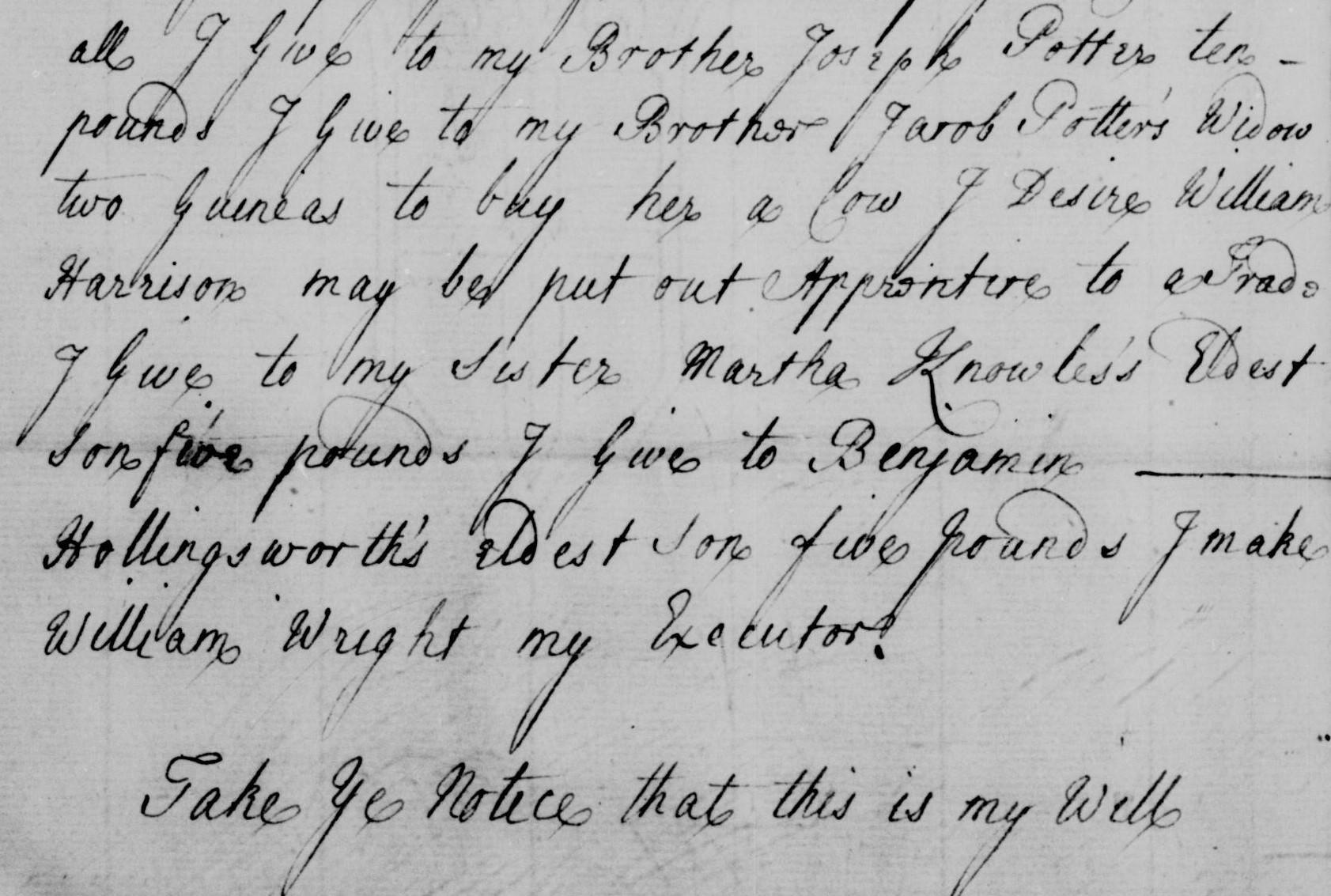

Martha’s brother James mentioned his sister Martha Knowles in his 1739 will, as well as his brother Jacob and his brother Joseph.

Martha’s father James Potter mentions his wife Ann in his 1719 will. James Potter married Ann Waterhurst in 1690 in Wirksworth, some seven miles from Darley. James occupation was innkeeper at Darley Bridge.

I did a search for Waterhurst (there was only a transcription available for that marriage, not a microfilm) and found no Waterhursts anywhere, but I did find many Warhursts in Derbyshire. In the older records, Warhust is also spelled Wearhurst and in a number of other ways. A Martha Warhurst died in Peak Forest, Derbyshire, in 1681. Her husbands name was missing from the deteriorated register pages. This may or may not be Martha Potter’s grandmother: the records for the 1600s are scanty if they exist at all, and often there are bits missing and illegible entries.

The only inn at Darley Bridge was The Three Stags Heads, by the bridge. It is now a listed building, and was on a medieval packhorse route. The current building was built in 1736, however there is a late 17th century section at rear of the cross wing. The Three Stags Heads was up for sale for £430,000 in 2022, the closure a result of the covid pandemic.

Another listed building in Darley Bridge is Potters Cottage, with a plaque above the door that says “Jonathan and Alice Potter 1763”. Jonathan Potter 1725-1785 was James grandson, the son of his son Charles Potter 1691-1752. His son Charles was also an innkeeper at Darley Bridge: James left the majority of his property to his son Charles.

Charles is the only child of James Potter that we know the approximate date of birth, because his age was on his grave stone. I haven’t found any of their baptisms, but did note that many Potters were baptised in non conformist registers in Chesterfield.

Potters Cottage

Jonathan Potter of Potters Cottage married Alice Beeley in 1748.

“Darley Bridge was an important packhorse route across the River Derwent. There was a packhorse route from here up to Beeley Moor via Darley Dale. A reference to this bridge appears in 1504… Not far to the north of the bridge at Darley Dale is Church Lane; in 1635 it was known as Ghost Lane after a Scottish pedlar was murdered there. Pedlars tended to be called Scottish only because they sold cheap Scottish linen.”

via Derbyshire Heritage website.

According to Wikipedia, the bridge dates back to the 15th century.

July 25, 2024 at 7:58 am #7542In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Shivering, Truella pulled the thin blanket over her head. Colder than a witches tit here, colder in summer than winter at home! It was no good, she may as well get up and go for a walk to try and warm up. Poking her head outside Truella gasped and coughed at the chill air. Shapes were becoming discernible in the dim pre dawn light, the other pods, the hedgerow, a couple of looming trees. Truella rummaged through her bag, hoping to find warm clothes yet knowing she hadn’t packed anything warm enough. Sighing, her teeth chattering, she pulled on everything she had in layers and pulled the blanket off the bed to use as a cape. With a towel over her head for extra warmth, she ventured out into the Irish morning.

The grass was sodden with dew and Truella’s feet were wet through and icy. Bracing her shoulders with determination, she forged ahead towards a gate leading into the next field. She struggled for a few minutes with the baler twine holding the gate closed, numb fingers refusing to cooperate. Cows watched her curiously, slowly munching. One lifted her tail and dropped a steaming splat on the grass, chewing continuously. I don’t think I could eat and do that at the same time.

Heading off across the field which sloped gently upwards, Treulla picked up her pace, keeping her eyes down to avoid the cow pats. By the time she reached the oak tree along the top hedge, the sun started to make an appearance over the hill. Warmer from the exercise, she gazed over the countryside. How beautiful it was with the mist in the valleys, and everything so green.

If only it was warmer!

“Are you cold then, is that why you’re decked out like that? From a distance I thought I was seeing a ghost in a cloak and head shawl!” The woman smiled at Truella from the other side of the hedgerow. “Sorry, did I startle you? You’ll get your feet soaked walking in that wet grass, climb over that stile over there, the lane here’s better for a morning walk.”

It sounded like good advice and the woman seemed pleasant enough. “Are you here for the games too?” Truella asked, readjusting the blanket and towel after navigating the stile.

“Yes, I am. I’m retired, you see,” the woman said with a wide grin. “It’s a wonderful thing, not that you’d know, you’re much to young.”

“That must be nice,” Truella replied politely. “I sometimes wish I was retired.”

“Oh, my dear! It’s wonderful! I haven’t had a job for years, but it’s the strangest thing, now that I’ve officially retired, there’s a marvellous feeling of freedom. I don’t have to do anything. Well, I didn’t have to do anything before I retired but one always feels one should keep busy, do productive things, be seen to be doing some kind of work to justify ones existance. Have you seen the old priory?”

“No, only just got here yesterday.”

“You’ll love it, it’s up this path here, follow me. But now I’ve retired,” the woman continued, “I get up in the morning with a sense of liberation. I can do as little as I want ~ funny thing is that I’ve actually been doing more, but there’s no feeling of obligation, no things to cross off a list. All I’m expected to do as a retired person is tick along, trying not to be much of a bother for as long as I can.”

“I wish I was retired!” exclaimed Truella with feeling. “I wish I didn’t have to do the cow goddess stall, it’ll be such a bind having to stand there all evening.” She explained about the coven and the stalls, and the depressing productivity goals.

“But why not get someone else to do the stall for you?”

“It’s such short notice and I don’t know anyone here. It’s an idea though, maybe someone will turn up.”

June 24, 2024 at 9:03 pm #7521In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

It was matins, the early break of dawn at cockcrow, and the sisters had been diligent to call everyone for prayers.

Mother Lorena was expounding on the powers of prayer while Eris was struggling to keep her friends awake after the short night.

“Our Sister Hildegard,” Mother Lorena was droning, as to make everything painfully clear to the newcomers “was one of the founding members of our secret order of nun-witches as you would like to say. But make no mistake, she tapped into a power much much older. The power of prayer of the early Christians was capable of great miracles…”

“If we’re here for a history lesson, hope she tells us more about the dragons…” muttered Truella, still groggy from her sleepless night.

As if the absurdly hearing-impaired Mother superior had heard the plea, she went on “It is that same power of prayer from the early covens of nun-witches that helped vanquish the hordes of dragon-boat riding invaders.”

“Did she say dragon??”

“Ssshttt!” Jeezel and Eris shushed Truella as they were struggling to keep up with the rosary count.

“Of course, I mean the viking hordes with their drakkar boats. Such be the tale forever embedded in our embroidered tapestries.”

“She didn’t say about the frogs nuns though, has she?” Truella ventured, hoping the hearing/inspiration spell would still work.

“I suppose the frog-nuns were symbols of transformation, alchemy — or mastery about the water element from which the invaders came, or maybe just waiting for a prince’s kiss… what should I know?” Eris shrugged, mildly annoyed. Her phone was busy spewing messages. Luckily the silent prayer was over, and everyone was invited to the breakfast in the great hall.

“What’s happened?” Jeezel ventured.

Eris sighed. “I’ll have to leave you for today. Another bank errand for Austreberthe. Hope it doesn’t become a habit… Luckily she’s asked Mother Lorena to allow me to use the covent’s portal to make haste.”

She turned to Truella. “I trust you with this Tru, please don’t make a mess of it while I’m gone. There are forces at play here, and we can’t be distracted; I’ll be back as soon as I can. We still have the crypts and the reanimated nuns to investigate, but I’m sure they can wait for a few hours more.”

Before Truella could protest, Eris was on her way.

June 16, 2024 at 10:30 pm #7486In reply to: Smoke Signals: Arcanas of the Quadrivium’s incense

The Morticians Guild:

Nemo Tenebris, and let me tell ya, he’s a character straight out of one of those dark romance novels. Tall, brooding, with tousled hair somewhere between charcoal and mahogany, he’s got that rugged charm that makes even the bravest witches’ hearts skip a beat. His hands are like an artist’s, always deliberate and precise, whether he’s handling ancient texts or, well, more corporeal tasks. His personality? Think intense and enigmatic, with occasional bursts of biting humor. He’s the type who’ll share a grim tale and then light the room with a grin that makes you question your reality. Don’t underestimate him – he’s a master of necromancy and has an uncanny sensitivity to life’s deepest mysteries.

Silas Gravewalker. An older gent, he looks as though he’s always expecting a foggy night – grey cloak, even greyer hair, and eyes the color of storm clouds. His demeanor is gentle but don’t mistake it for weakness. He’s the wise old guardian of the Guild, carrying centuries of rituals, chants, and incantations within him. Silas is a remarkable blend of grandfatherly wisdom and hidden strength, and he’s a calming presence in the midst of chaos. His sense of humor is dryer than the Outback in summer, subtle yet striking at just the right moments. When Silas speaks, you listen, because his words are often tinged with layers of arcane meaning.

Rufus Blackwood: Enter Rufus Blackwood, the stoic guardian of the guild. He’s tall and broad-shouldered, with a presence that commands both respect and a shiver down the spine. His hair is a dusty shade of midnight black, streaked with the occasional silver – probably from the weight of the secrets he carries. His eyes are a pale grey, like the fog rolling off a moor, always scanning, always measuring. He’s perpetually clad in a long, leather duster coat that sweeps the floor as he glides across the room.

Personality-wise, Rufus is the strong, silent type, but when he speaks, it feels like ancient tombs whispering forgotten wisdom. He’s got a dry humor that surfaces in the most unexpected moments, like a ray of moonlight in a pitch-black night. He’s fiercely protective of his coven and guildmates, and there’s a sense of old-world honor about him. Underneath that granite exterior is a surprisingly tender heart that only a select few have glimpsed.

Garrett Ashford: Now, Garrett Ashford, he’s a bit of a dandy, as far as morticians go. Picture a man of average height but with presence larger than life. His hair is a striking ash blonde, always perfectly coiffed, and his attire is meticulously sharp – tailored suits, often in dark, rich fabrics with just a hint of eccentricity, like a red silk handkerchief or a silver pocket watch. His eyes are a sharp, pale blue, twinkling with a touch of playful mischief.

Garrett’s got a personality as polished as his appearance. He’s charismatic, with a knack for easing tensions with a well-timed joke or a charming smile. Though he might come off as a bit of a showman, make no mistake – Garrett’s got depth and a sharp mind. He’s a skilled embalmer and incantation master, knowing just the right touch to handle even the most delicate of cases. His flair for the dramatic doesn’t overshadow his competence; it complements it. He’s the kind of bloke who can discuss the darkest of topics with a light-hearted grace, making him a bit of a paradox but undeniably captivating.

March 24, 2024 at 9:59 pm #7413

March 24, 2024 at 9:59 pm #7413In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

It wasn’t until late the following afternoon that Truella, with a pang of guilt, remembered Roger. Frella grinned sheepishly and said that she had forgotten him too.

“But you know what? Wait, let me show you the tile I bought in Brazil.” Frella trotted off to find her suitcase.

“Look what it says on the bit of paper that came with it:

Function: The Freevole tile embodies the essence of empowerment and autonomy. It serves as a reminder and a guide for those standing at life’s many crossroads, facing decisions that may seem overwhelming. This tile encourages the holder to recognize their inner strength and the ability to choose their path confidently, even when faced with seemingly insurmountable challenges.

At the center of the tile, there is a small vole standing at a crossroads where waters intersect, with dry earth visible behind it. The scene depicts sheets of water overlapping on both sides of the vole, creating a sense of inundation, yet there is an opening ahead, suggesting a path or choice to be made.We need to backtrack a bit with Roger. Look what it says here:

What that vole hadn’t realized was that he had to backtrack a bit. There was no way ahead or to the sides, but the way out was behind him.

See what I mean?”

Truella squinted at Frella. “What?”

Sighing, Frigella thrust the bit of paper at her friend. “Read the rest of it!”

The Vole: The vole symbolizes the individual facing a decision point or crossroads in life. Its presence suggests vulnerability, but also resilience and adaptability.

Crossing of Waters: The intersection of waters represents the convergence of different paths or possibilities. It symbolizes the complexities and challenges of decision-making, where multiple options overlap and intertwine.

Dry Earth Behind: The dry earth behind the vole symbolizes stability, past experiences, or familiar ground. It represents the foundation upon which decisions are based and serves as a reminder of where one has come from.

Overlap of Drowned Sheets of Water: The drowned sheets of water on both sides signify the potential consequences or risks associated with each choice. They represent the unknown and the possibility of being overwhelmed by circumstances.

Opening Ahead: The opening ahead signifies opportunity, hope, and the possibility of forging a new path. It represents the future and the freedom to make choices that lead to growth and fulfilment.Families: This tile is aligned with the Vold family, known for their connection to transformation, challenge, and the breaking of old systems to make way for the new. The Vold energy within the Freevole tile emphasizes the importance of facing challenges head-on and using them as opportunities for growth and empowerment.

Significance: The scene depicted on the Freevole tile, with the vole at a crossroads between inundation and dry earth, symbolizes the moments in life where we must make significant choices amidst emotional or situational floods. The waters represent challenges and emotions that may threaten to overwhelm, while the dry earth symbolizes the solid ground of our inner strength and determination. The path ahead, though uncertain, indicates that there is always a way forward, guided by our autonomy and personal power.

As an advice: When encountering the Freevole tile, take it as a sign to pause and reflect on your current crossroads. It urges you to tap into your inner resilience and recognize that you have the power to navigate your life’s journey. The choices before you, while daunting, are opportunities to assert your independence and steer your life according to your true desires and values. Trust in your ability to make decisions that will lead you to your chosen path of fulfillment and growth. Remember, the floods of challenge bring with them the nourishment needed for new beginnings; it is within your power to find the opening and move forward with courage and confidence.

The motif of the Freevole, standing determined and attentive amidst the forces of nature, serves as a potent symbol of the power within each individual to face life’s uncertainties and emerge stronger for having made their own choices.“Ok so in a nutshell,” Truella replied slowly, “Roger’s crossroads took him to Brazil and ours took us here, and that’s all that needs to be said about it. Right?”

“Exactly!”

March 13, 2024 at 7:10 pm #7406In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

During the renovations on Brightwater Mill Truella’s parents rented a cottage nearby. It was easier to supervise the builders if they were based in the area, and it would be a nice place for Truella to spend the summer. One of the builders had come over from Ireland and was camping out in the mill kitchen. He didn’t mind when Truella got in the way while he was working, and indulged her wish to help him. He gave her his smallest trowel and a little bucket of plaster, not minding that he’d have to fix it later. He was paid by the hour after all.

When the builder mentioned that his daughter Frigella was the same age, Truella’s mother had an idea. Truella needed a little friend to play with, to keep her from distratcing the builders from their work.

And so a few days later, Frigella arrived for the rest of the summer holidays. He father continued to camp out in the mill, and Frigella stayed with Truella. But even with the new friend to play with, Truella still wanted to plaster the walls with her little trowel. Frigella didn’t want to stay cooped up all day in the dusty mill with her father keeping an eye on her all day, and suggested that they go and dig a hole somewhere in the garden to find treasure.

Truella carried the little trowel around with her everywhere she went that summer, and Frigella started to call her Trowel. Truella retaliated by calling her friend Fridge Jelly, saying what a silly name it was. It wasn’t until she burst into tears that Truella felt remorseful and kindly asked Frigella what she would like to be called, but it had to be something that didn’t remind Truella of fridges and jellys. Frigella admitted that she’s always hated the G in her name and would quite like to be called Frella instead. Truella replied that she didn’t mind being called Trowel though, in fact she quite liked it.

The girls spent many school summer holidays together over the years, but it wasn’t until Truella was older and staying in one of the apartments with a boyfriend that she found the trunk in the attic. She put it in the boot of the car without opening it. She only had the weekend with the new guy and there were other activities on the agenda, after all. Work and other events occupied her when she returned home, and the trunk was put in a closet and forgotten.

March 10, 2024 at 8:54 am #7401In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

It may surprise you, dear reader, to hear the story of Truella and Frella’s childhood at a Derbyshire mill in the early 1800s. But! I hear you say, how can this be? Read on, dear reader, read on, and all will be revealed.

Tilly, daughter of Everard Mucklewaite, miller of Brightwater Mill, was the youngest of 17 children. Her older siblings had already married and left home when she was growing up, and her parents were elderly. She was somewhat spoiled and allowed a free rein, which was unusual for the times, as her parents had long since satisfied the requirements for healthy sons to take over the mill, and well married daughters. She was a lively inquisitive child with a great love of the outdoors and spent her childhood days wandering around the woods and the fields and playing on the banks of the river. She had a great many imaginary friends and could hear the trees whisper to her, in particular the old weeping willow by the mill pond which she would sit under for hours, deep in conversation with the tree.

Tilly didn’t have any friends of her own age, but as she had never known human child friends, she didn’t feel the loss of it. Her older sisters used to talk among themselves though, saying she needed to play with other children or she’d never grow up and get out of her peculiar ways. Between themselves (for the parents were unconcerned) they sent a letter to an aunt who’d married an Irishman and moved with him to Limerick, asked them to send over a small girl child if they had one spare. As everyone knew, there were always spare girls that parents were happy to get rid of, if at all possible, and by return post came the letter announcing the soon arrival of Flora, who was a similar age to Tilly.

It was a long strange journey for little Flora, and she arrived at her new home shy and bewildered. The kitchen maid, Lucy, did her best to make her feel comfortable. Tilly ignored her at first, and Everard and his wife Constance were as usual preoccupied with their own age related ailments and increasing senility.

One bright spring day, Lucy noticed Flora gazing wistfully towards the millpond, where Tilly was sitting on the grass underneath the willow tree.

“Go on, child, go and sit with Tilly, she don’t bite, just go and sit awhile by her,” Lucy said, giving Flora a gentle push. “Here, take this,” she added, handing her two pieces of plum cake wrapped in a blue cloth.

Flora did as she was bid, and slowly approached the shade of the old willow. As soon as she reached the dangling branches, the tree whispered a welcome to her. She smiled, and Tilly smiled too, pleased and surprised that the willow has spoken to the shy new girl.

“Can you hear willow too?” Tilly asked, looking greatly pleased. She patted the grass beside her and invited Flora to sit. Gratefully, and with a welcome sigh, Flora joined her.

Tilly and Flora became inseperable friends over the next months and years, and it was a joy for Tilly to introduce Flora to all the other trees and creatures in their surroundings. They were like two peas in a pod.

Over the years, the willow tree shared it’s secrets with them both.

One summer day, at the suggestion of the willow tree, Tilly and Flora secretly dug a hole, hidden from prying eyes by the long curtain of hanging branches. They found, among other objects which they kept carefully in an old trunk in the attic, an old book, a grimoire, although they didn’t know it was called a grimoire at the time. In fact, they were unable to read it, as girls were seldom taught to read in those days. They secreted the old tome in the trunk in the attic with the other things they’d found.

Eventually the day came when Tilly and Flora were found husbands and had to leave the mill for their new lives. The trunk with its mysterious contents remained in the dusty attic, and was not seen again until almost 200 years later, when Truella’s parents bought the old mill to renovate it into holiday apartments. Truella took the trunk for safekeeping.

When she eventually opened it to explore what it contained, it all came flooding back to her, her past life as Tilly the millers daughter, and her friend Flora ~ Flora she knew was Frigella. No wonder Frella had seemed so familiar!

February 26, 2024 at 8:35 am #7389In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Well, it’s a long story, are you sure you want to hear it?”

“Tell me everything, right from the beginning. You’re the one who keeps saying we have plenty of time, Truella. I shall quite enjoy just sitting here with a bottle of wine listening to the story,” Frigella said, feeling all the recent stress pleasantly slipping away.

“Alright then, you asked for it!” Truella said, topping up their glasses. The evening was warm enough to sit outside on the porch, which faced the rising moon. A tawny owl in a nearby tree called to another a short distance away. “It’s kind of hard to say when it all started, though. I suppose it all started when I joined that Arkan coven years ago and the focus wasn’t on spells so much as on time travel.”

“We used to travel to times and places in the past,” Truella continued, “Looking back now, I wonder how much of it we made up, you know?” Frigella nodded. “Preconceptions, assumptions based on what we thought we knew. It was fun though, and I’m pretty sure some of it was valid. Anyway, valid or not, one thing leads to another and it was fun.

“One of the trips was to this area but many centuries ago in the distant past. The place seemed to be a sort of ancient motorway rest stop affair, somewhere for travellers to stay overnight on a route to somewhere. There was nothing to be found out about it in any books or anything though, so no way to verify it like we could with some of our other trips. I didn’t think much more about it really, we did so many other trips. For some reason we all got a bit obsessed with pyramids, as you do!”

They both laughed. “Yeah, always pyramids or special magical stones,” agreed Frigella.

“Yeah that and the light warriors!” Truella snorted.

“So then I found a couple of pyramids not far away, well of course they weren’t actually pyramids but they did look like they were. We did lots of trips there and made up all sorts of baloney between us about them, and I kept going back to look around there. We used to say that archaeologists were hiding the truth about all the pyramids and past civilizations, quite honestly it’s a bit embarrassing now to remember that but anyway, I met an actual archaeologist by chance and asked her about that place. And the actual history of it was way more interesting than all that stuff we’d made up or imagined.

The ruins I’d found there were Roman, but it went further back than that. It was a bronze age hill fort, and later Phoenician and Punic, before it was Roman. I asked the archaeologist about Roman sites and how would I be able to tell and she showed me a broken Roman roof tile, and said one would always find these on a Roman site.

I found loads over the years while out walking, but then I found one in the old stone kitchen wall. Here, let me fetch another bottle.” Truella got up and went inside, returning with the wine and a dish of peanuts.

“So that’s when I decided to dig a hole in the garden and just keep digging until I found something. I don’t know why I never thought to do that years ago. I tell you what, I think everyone should just dig a hole in their garden, and just keep digging until they find something, I can honestly say that I’ve never had so much fun!”

“But couldn’t you have just done a spell, instead of all that digging?” Frigella asked.

“Oh my god, NO! Hell no! That wouldn’t be the same thing at all,” Truella was adamant. “In fact, this dig has made me wonder about all our spells to be honest, are we going too fast and missing the finds along the way? I’ve learned so much about so many things by taking it slowly.”

“Yeah I kinda know what you mean, but carry on with the story. We should discuss that later, though.”

“Well, I just keep finding broken pottery, loads of it. We thought it was all Roman but some of it is older, much older. I’m happy about that because I read up on Romans and frankly wasn’t impressed. Warmongering and greedy, treated the locals terribly. Ok they made everything look nice with the murals and mosaics and what not, and their buildings lasted pretty well, but who actually built the stuff, not Romans was it, it was the slaves. Still, I wasn’t complaining, finding Roman stuff in the garden was pretty cool. But I kept wishing I knew more about the people who lived here before they came on the rampage taking everything back to Rome. Hey, let me go and grab another bottle of wine.”

Frigella was feeling pleasantly squiffy by now. The full moon was bright overhead, and she reckoned it was light enough to wander around the garden while Truella was in the kitchen. As she walked down the garden, the tawny owl called and she looked up hoping to see him in the fig tree. She missed her step and fell over a bucket, and she was falling, falling, falling, like Alice down the rabbit hole.

The fall was slow like a feather wafting gently down and she saw hundreds of intriguing fragments of objects and etchings and artefacts on the sides of the hole and she drifted slowly down. At last she came to rest at the bottom, and found herself in an arched gallery of mirrors and tiles and doors. On every surface were incomplete drawings and shreds of writings, wondrous and fascinating. She didn’t immediately notice the hippocampus smiling benignly down at her. He startled her a little, but had such a pleasant face that she smiled back up at him. “Where am I?” she asked.

“You’d be surprised how many people ask me that.” he replied, with a soft whicker of mirth. “Not many realise that they’ve called on me to help them navigate. Now tell me, where is it you want to go?”

“Well,” Frigella replied slowly, “Now that you ask, I’m not entirely sure. But I’m pretty sure Truella would like to see this place.”

February 6, 2024 at 12:11 am #7352

February 6, 2024 at 12:11 am #7352In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“If it’s nae Frigella O’green! Fancy seeing ye ‘ere!”

Frigella stiffened. She’d know that accent and the dank tang of peat moss anywhere. She’d have smelt it sooner if it weren’t for the brewing coffee. She must be getting soft … or maybe it was the sour smell of smoke clogging up her nostrils; she’d not been able to shake the stench since the debacle that morning. Turning away from Aaron, the pleasant young barista serving her, she willed her lips into a smile – no harm in being civil! It was a long time since all the Scottish shenanigans and word amongst the witches was the Scots Coven were trying to tidy up their act.

“Well, If it’s not Aggie Bog now!” Frigella leaned in for a cool peck on the cheek. “And what brings you to these parts? Let me buy you a coffee and we can catch up?”

Aggie sniggered. ” Ye pay for it?” She pushed Frigella aside and approached the counter. Aaron’s eyes widened and Frigella had to admit Aggie cut a striking figure in her tiny black top and leather leggings. As a child she’d been taunted and called fat, but now she was best described as Rubenesque, and clearly had learned how to use her assets.

I bet those pants squeak when she walks.

Aggie leaned forward and Aaron’s gaze flicked toward her abundant cleavage. “A double black insomnia fur me, on the hoose.” As Aaron started to protest, Aggie waved several plump fingers towards his face and Frigella saw his eyes were now dark and glazed. “Whirling ‘n’ twirling a muckle puff o’ rowk,” crooned Aggie. “Ye’ll dae as ah say or caw intae a ….”

Frigella clasped Aggie’s wrist. Thank god the lunch crowd had gone and the cafe was nearly empty apart from an older man reading his paper by the window. “Aggie Bog! Shame on you! That’s not the way we do things here.”

May 16, 2023 at 1:37 pm #7243In reply to: Washed off the sea ~ Creative larks

Using a random generator for the next challenge with 5 objects.

- straw

- pop can

- pencil holder

- Christmas ornament

- turtle

🐋

In the dreary town of Ravenwood, where shadows loomed and the wind howled through the empty streets, there was one house that stood out above the rest. It was the old mansion at the end of the road, shrouded in mystery and secrets. No one had lived there for years, but whispers of strange happenings and eerie lights could be heard wafting through the air.

One stormy night, a young writer named Edgar arrived in Ravenwood seeking inspiration for his latest story. Drawn to the mansion by a strange force, he ventured inside, and found himself face to face with a peculiar sight. A straw sat on the table, next to a pop can and a pencil holder, and a Christmas ornament hung from a cobweb in the corner. But it was the turtle, a giant terrapin that seemed to be staring back at him with knowing eyes, that caught his attention.

Edgar couldn’t shake the feeling that something was amiss, that the objects in the room were connected in some strange way. As he looked closer, he noticed that a thick layer of dust had settled on everything, as if no one had been there in years. And yet, the pop can still seemed to be fizzing, the straw stirred as if someone had just taken a sip, and the turtle’s eyes seemed to glow in the dim light.

Suddenly, a voice from behind him made Edgar jump. It was the ghost of the previous owner, who had died under mysterious circumstances years ago. The ghost revealed that the objects in the room had been cursed by a vengeful witch who had once lived in the nearby forest. Each object was imbued with a terrible power, and whoever possessed them would be consumed by darkness.

Edgar knew he had to escape, but as he turned to run, he felt a strange force pulling him towards the turtle. He tried to resist, but the turtle’s eyes seemed to hypnotize him, drawing him in closer and closer. Just as he was about to touch it, the turtle suddenly snapped its jaws shut, and Edgar woke up back in his own bed, drenched in sweat.

He realized it had all been a nightmare, but as he looked down at his feet, he saw the turtle from his dream, sitting innocently at the end of his bed. Suddenly, he remembered the words of the ghost, and knew he had to destroy the cursed objects before it was too late. With trembling hands, he picked up the turtle, and opened his window to cast it out into the night. But as he did so, he caught a glimpse of his own reflection in the glass, and saw that his eyes had turned a bright shade of red. The curse had already taken hold, and Edgar knew he was doomed to a life of darkness and despair.

Bit dark, Whale!

March 14, 2023 at 8:37 pm #7166

March 14, 2023 at 8:37 pm #7166In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Godfrey had been in a mood. Which one, it was hard to tell; he was switching from overwhelmed, grumpy and snappy, to surprised and inspired in a flicker of a second.

Maybe it had to do with the quantity of material he’d been reviewing. Maybe there were secret codes in it, or it was simply the sleep deprivation.

Inspired by Elizabeth active play with her digital assistant —which she called humorously Whinley, he’d tried various experiments with her series of written, half-written, second-hand, discarded, published and unpublished, drivel-labeled manuscripts he could put his hand on to try to see if something —anything— would come out of it.

After all, Liz’ generous prose had always to be severely edited to meet the editorial standards, and as she’d failed to produce new best-sellers since the pandemic had hit, he’d had to resort to exploring old material to meet the shareholders expectations.

He had to be careful, since some were so tartied up, that at times the botty Whinley would deem them banworthy. “Botty Banworth” was Liz’ character name for this special alternate prudish identity of her assistant. She’d run after that to write about it. After all, “you simply can’t ignore a story character when they pop in, that would be rude” was her motto.

So Godfrey in turn took to enlist Whinley to see what could be made of the raw material and he’d been both terribly disappointed and at the same time completely awestruck by the results. Terribly disappointed of course, as Whinley repeatedly failed to grasp most of the subtleties, or any of the contextual finely layered structures. While it was good at outlining, summarising, extracting some characters, or content, it couldn’t imagine, excite, or transcend the content it was fed with.

Which had come as the awestruck surprise for Godfrey. No matter how raw, unpolished, completely off-the-charts rank with madness or replete with seeming randomness the content was, there was always something that could be inferred from it. Even more, there was no end to what could be seen into it. It was like life itself. Or looking at a shining gem or kaleidoscope, it would take endless configurations and had almost infinite potential.

It was rather incredible and revisited his opinion of what being a writer meant. It was not simply aligning words. There was some magic at play there to infuse them, to dance with intentions, and interpret the subtle undercurrents of the imagination. In a sense, the words were dead, but the meaning behind them was still alive somehow, captured in the amber of the composition, as a fount of potentials.

What crafting or editing of the story meant for him, was that he had to help the writer reconnect with this intent and cast her spell of words to surf on the waves of potential towards an uncharted destination. But the map of stories he was thinking about was not the territory. Each story could be revisited in endless variations and remain fresh. There was a difference between being a map maker, and being a tour-operator or guide.

He could glimpse Liz’ intention had never been to be either of these roles. She was only the happy bumbling explorer on the unchartered territories of her fertile mind, enlisting her readers for the journey. Like a Columbus of stories, she’d sell a dream trusting she would somehow make it safely to new lands and even bigger explorations.

Just as Godfrey was lost in abyss of perplexity, the door to his office burst open. Liz, Finnley, and Roberto stood in the doorway, all dressed in costumes made of odds and ends.

“You are late for the fancy dress rehearsal!” Liz shouted, in her a pirate captain outfit, her painted eye patch showing her eye with an old stitched red plush thing that looked like a rat perched on her shoulder supposed to look like a mock parrot.

“What was the occasion again?”

“I may have found a new husband.” she said blushing like a young damsel.

Finnley, in her mummy costume made with TP rolls, well… did her thing she does with her eyes.

March 7, 2023 at 8:20 pm #6774In reply to: Stories: New Found Pages

As they trekked through the endless dunes, Lord Gustard could barely contain his excitement. The thought of discovering the bones of the legendary giant filled him with a childlike wonder, and he eagerly scanned the horizon for any sign of their destination. As the fearless leader of the group, he had a deep-seated passion for adventure and exploration, a love for pith helmets. However, his tendency to get lost in his own thoughts at the most inconvenient times could sometimes get him in tricky situations. Despite this, he has an unshakable determination to succeed and a deep respect for the cultures and traditions of the places he visits.

Lady Floribunda, on the other hand, was the picture of patience and duty. She knew that this journey was important to her husband and she supported him unwaveringly, even as she silently longed for the comforts of home. Her first passion was for gossips and the life of socialites —but there was hardly any gossip material in the desert, so she fell back to her second passion, botany, that would often get her lost in her own world, examining and cataloging the scant flora and fauna they encountered on their journey. It wasn’t unusual to hear her at time talking to plants as if they were her dolls or children.

Cranky, meanwhile, couldn’t help but roll her eyes at Lord Gustard’s exuberance. “I swear, if I have to listen to one more of his whimsical ramblings, I’ll go mad,” she muttered to herself. Her tendency to grumble about the hardships of their journey had taken a turn for the worse, considering the lack of comfort from the past nights. She was as sharp-tongued as she was pragmatic, with a love for tea and crumpets that bordered on obsessive. Despite her grumpiness, she has a heart of gold and a deep affection for her companions, and especially young Illi.

Illi, on the other hand, was thrilled by every new discovery along the way. Whether it was a curious beetle scuttling across the sand or a shimmering oasis in the distance, she couldn’t help but express her excitement with a constant stream of questions and exclamations. Illi was a bright and enthusiastic young girl, with a passion for adventure and a wide-eyed wonder at the world around her. She had a tendency to burst into song at the most unexpected moments.

Tibn Zig and Tanlil Ubt remained loyal and steadfast, shrugging off any incongruous spur of the moment extravagant outburst from Gustard. Their experience in the desert had taught them to stay calm and focused, no matter what obstacles they might encounter. But behind the stoic façade, they had a penchant for telling tall tales and playing practical jokes on their companions. Their mischievousness was however only for good fun, and they had become fiercely loyal to Lord Gustard after he’d rescued them from sand bandits who were planning to sell them as slave. Needless to say, they would have done whatever it takes to keep the Fergusson family safe.

Illi was hoping for eccentric traders and desert nomads to fortune-seeking treasure hunters and conniving bandits, but for miles it was just plain unending desert. The worst they found on their path were unending sand dunes, a few minuscule deadly scorpions, and mostly contending with the harsh desert sun beating down upon them. Finally, after days of wandering through the desert, they reached their destination.

As they approached Tsnit n’Agger, the landscape began to change. The sand dunes gave way to rocky cliffs and towering red sandstone formations, and the air grew cooler and more refreshing. The group pressed on, their spirits renewed by the prospect of discovering the secrets of the legendary giant’s bones.

At last, they arrived at the entrance to the giant’s cave. Lord Gustard led the way, his torch casting flickering shadows on the walls as they descended deeper into the earth. The air grew colder and damper, and the sounds of dripping water echoed around them.

As they turned a corner, they suddenly found themselves face to face with the giant’s bones. Towering above them, the massive skeletal structure filled the cavern from floor to ceiling. The sight of the giant’s bones towering above them was awe-inspiring, and Lord Gustard was practically bouncing with excitement. The group behind him was in awe, even Cranky, as they were taking in the enormity and majesty of the ancient creature.

Floribunda and Cranky exchanged a weary but amused look, while Illi gazed up at the bones with wide-eyed wonder.

“Let’s get to work,” Lord Gustard declared, his enthusiasm undimmed. And with that, they set to the task of uncovering the secrets of the legendary giant, each in their own way.

February 8, 2023 at 10:08 pm #6514In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Xavier offered the following quirk: “being the holder of continuity”

Quirk accepted.

Your quest takes place in the ghost town of Midnight, where time seems to have stood still. The townspeople are all frozen in time, stuck in their daily routines and unable to move on. Your mission is to find the missing piece of continuity, a small hourglass that will set time back in motion and allow the townspeople to move forward.

The clue to finding the hourglass lies within a discarded pocket watch that can be found in the mayor’s office. You must unscrew the back and retrieve a hidden key. The key will unlock a secret compartment in the town clock tower, where the hourglass is kept.

Be careful as you search for the hourglass, as the town is not as abandoned as it seems. Spectral figures roam the streets, and strange whispers can be heard in the wind. You may also encounter a mysterious old man who seems to know more about the town’s secrets than he lets on.

Proof of completion can be shown by taking a photo of the hourglass and the pocket watch, and sending it to the game’s creators.

Good luck!

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

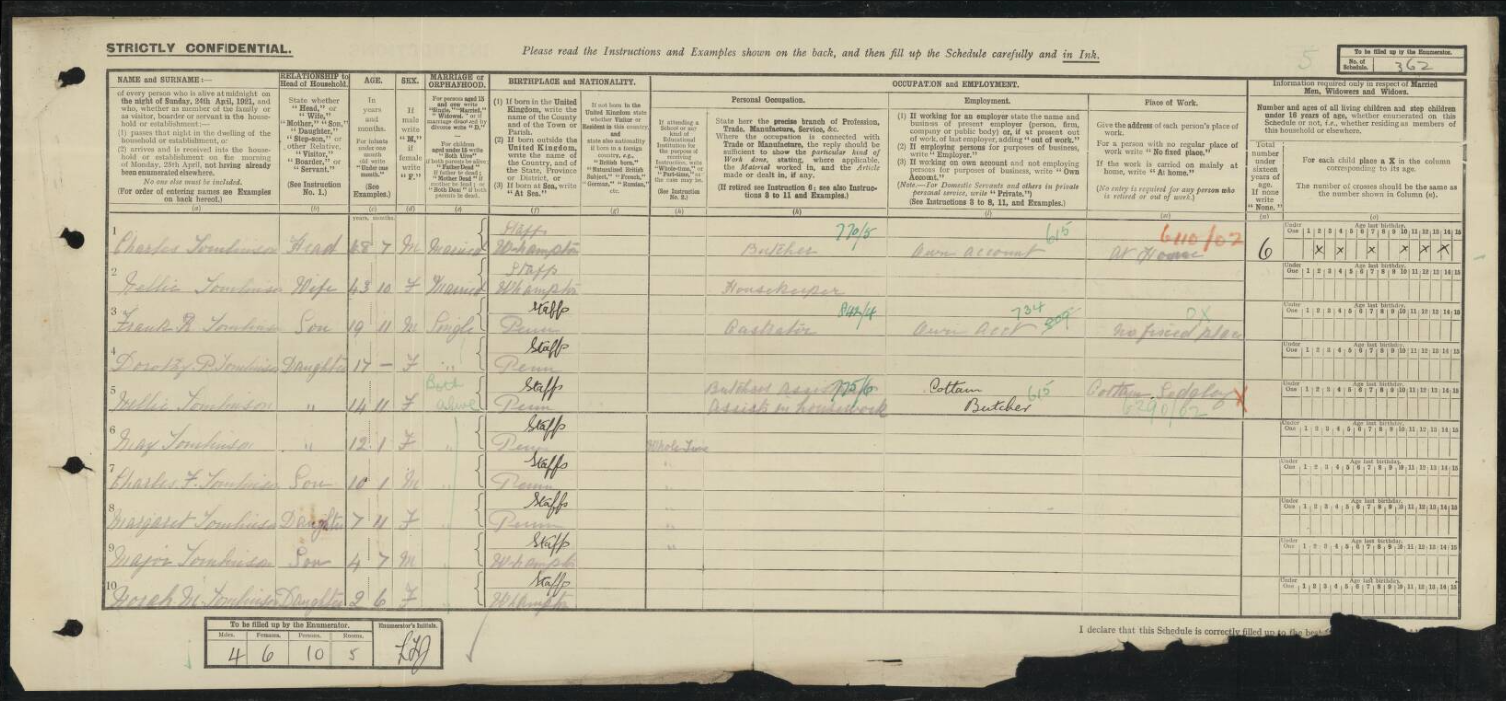

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

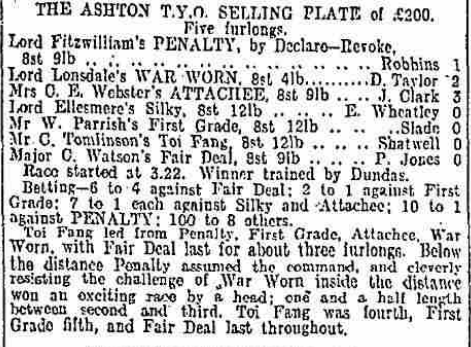

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

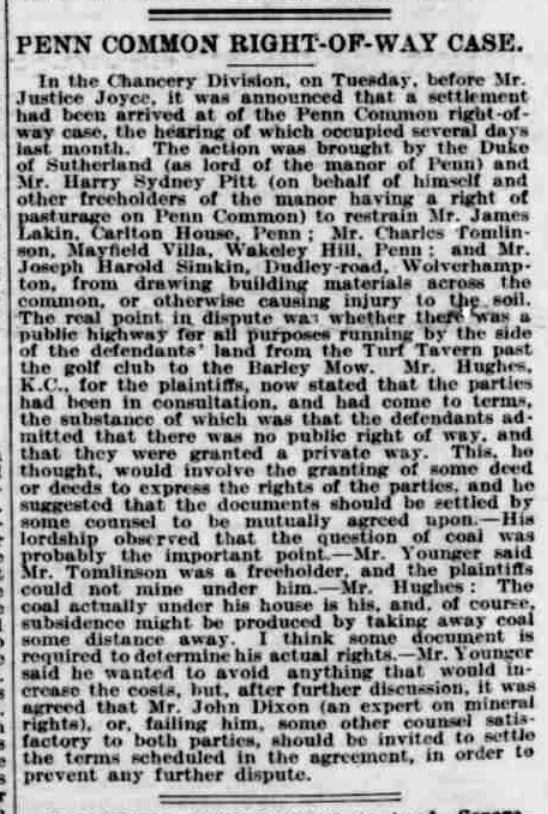

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

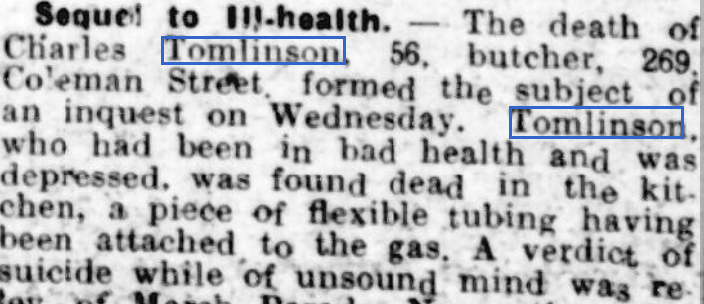

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

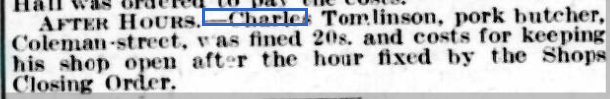

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Robert Staley

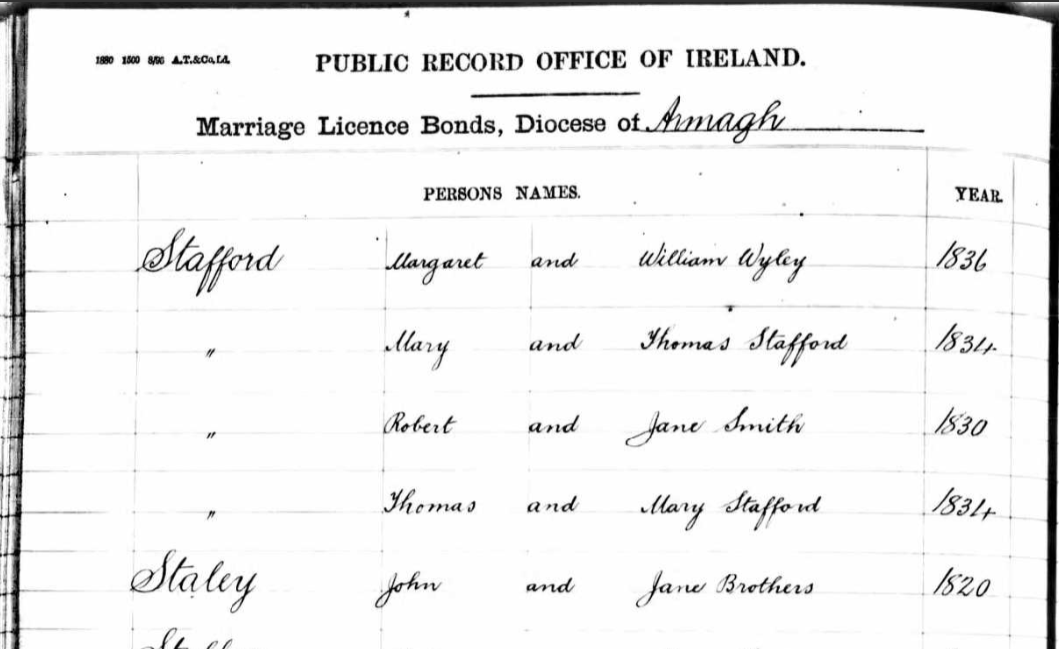

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

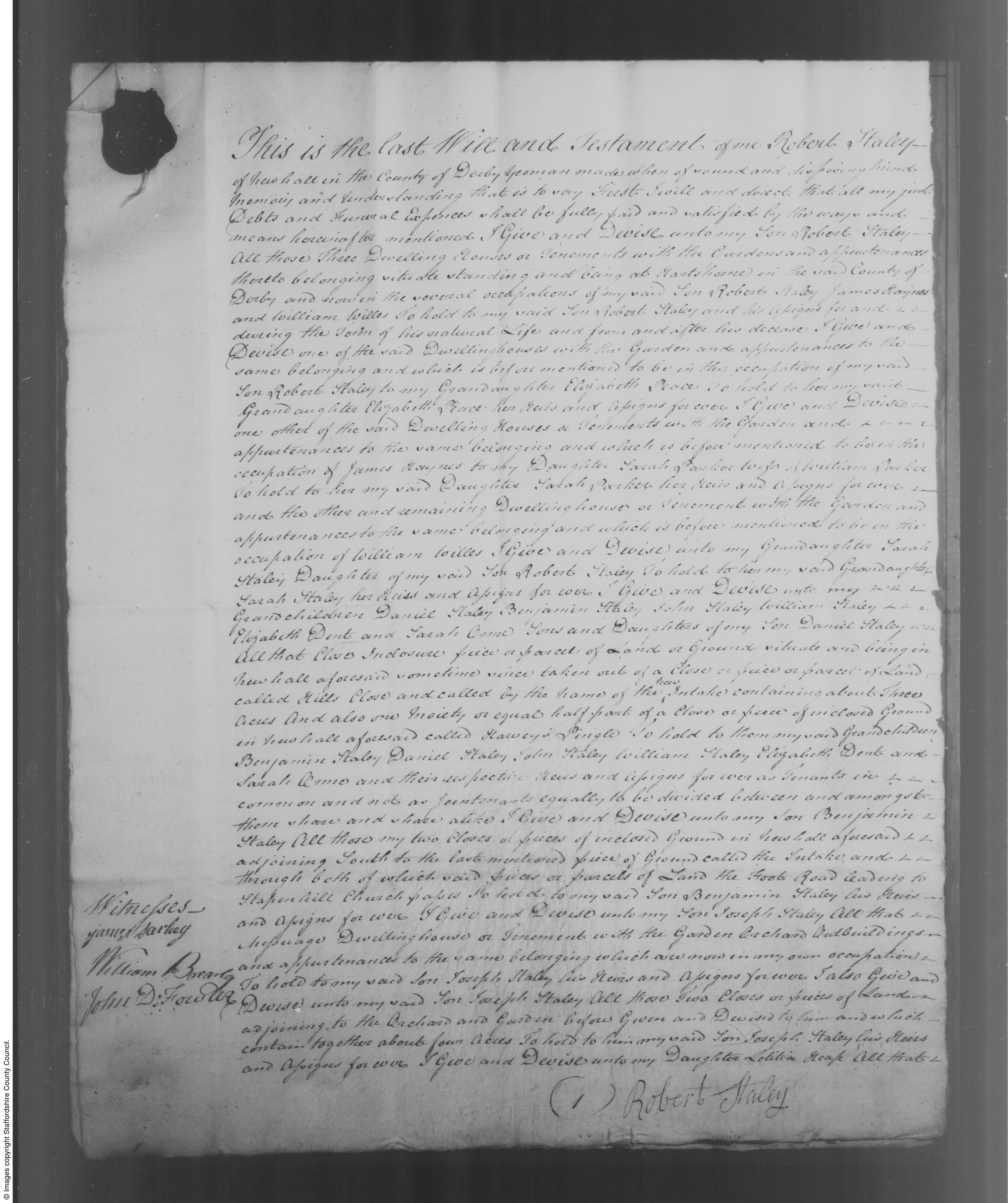

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

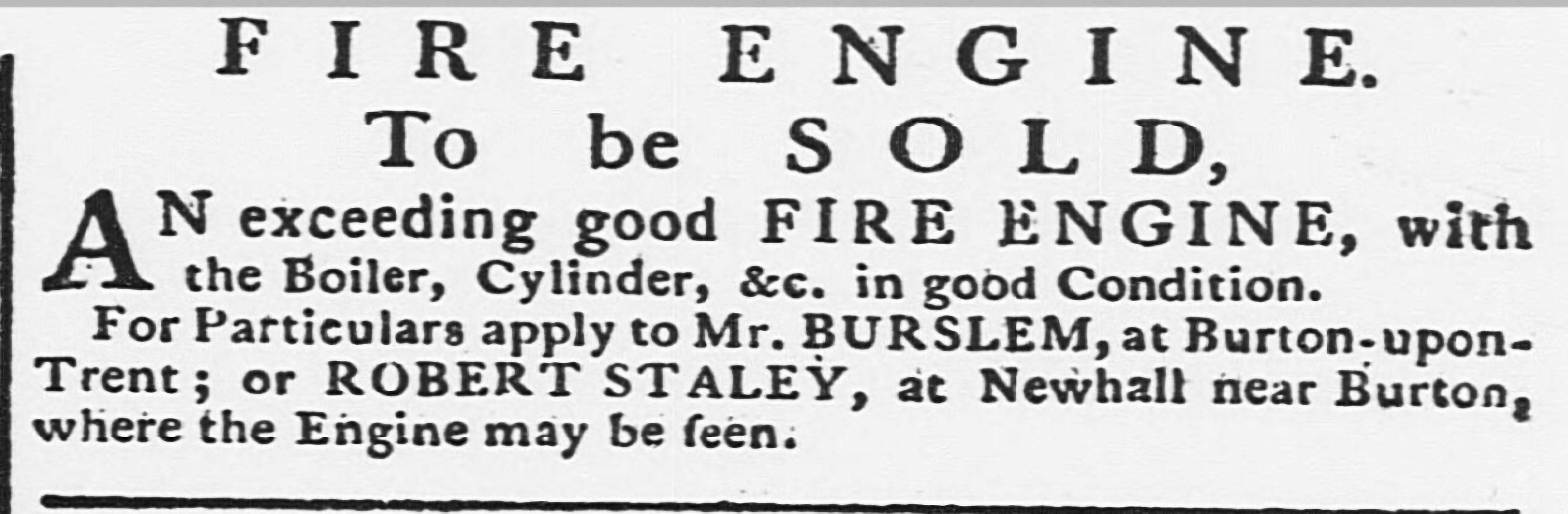

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

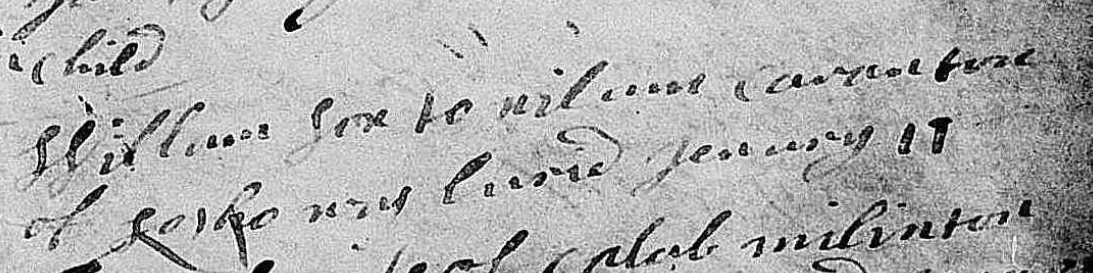

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

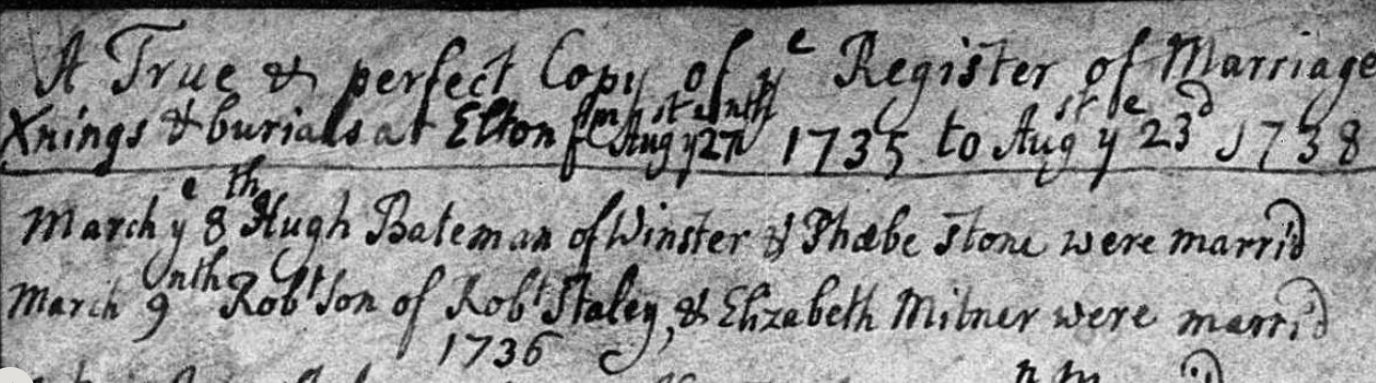

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

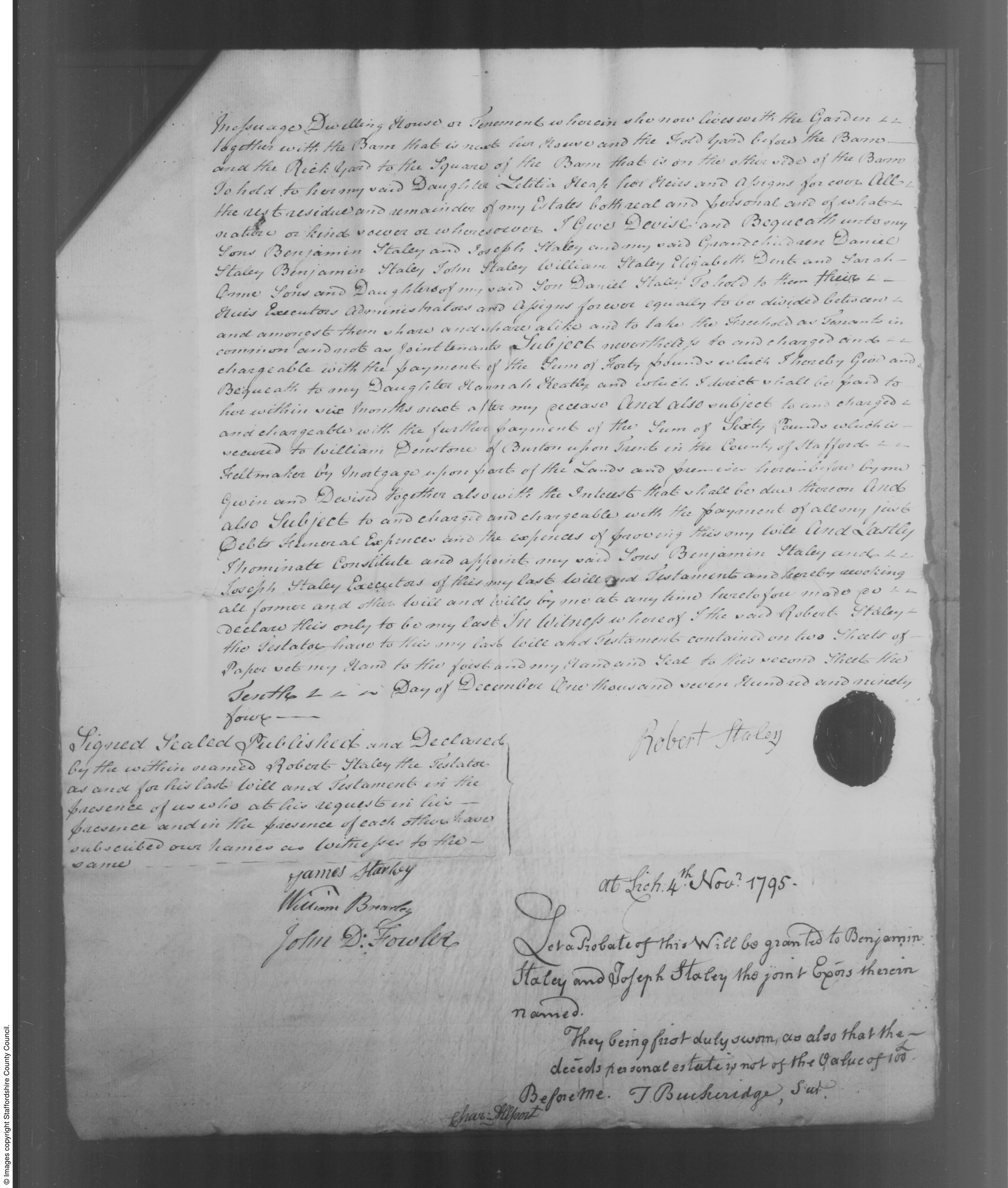

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.

I give, devise and bequeath to Humphrey Trafford Nadin of Church Gresely in the said County of Derby Esquire and John Wilkinson of Newhall aforesaid yeoman all my messuages, lands, tenements, hereditaments and real and personal estates to hold to them, their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns until Richard Moon the youngest of my reputed sons by Elizabeth Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years upon trust that they, my said trustees, (or the survivor of them, his heirs, executors, administrators or assigns), shall and do manage and carry on my farm at Newhall aforesaid and pay and apply the rents, issues and profits of all and every of my said real and personal estates in for and towards the support, maintenance and education of all my reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon until the said Richard Moon my youngest reputed son shall attain his said age of twenty one years and equally share and share and share alike.

And it is my will and desire that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall recruit and keep up the stock upon my farm as they in their discretion shall see occasion or think proper and that the same shall not be diminished. And in case any of my said reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon shall be married before my said reputed youngest son shall attain his age of twenty one years that then it is my will and desire that non of their husbands or wives shall come to my farm or be maintained there or have their abode there. That it is also my will and desire in case my reputed children or any of them shall not be steady to business but instead shall be wild and diminish the stock that then my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority in their discretion to sell and dispose of all or any part of my said personal estate and to put out the money arising from the sale thereof to interest and to pay and apply the interest thereof and also thereunto of the said real estate in for and towards the maintenance, education and support of all my said reputed children by the said

Elizabeth Moon as they my said trustees in their discretion that think proper until the said Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years.Then I give to my grandson Daniel Staley the sum of ten pounds and to each and every of my sons and daughters namely Daniel Staley, Benjamin Staley, John Staley, William Staley, Elizabeth Dent and Sarah Orme and to my niece Ann Brearly the sum of five pounds apiece.

I give to my youngest reputed son Richard Moon one share in the Ashby Canal Navigation and I direct that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority to pay and apply all or any part of the fortune or legacy hereby intended for my youngest reputed son Richard Moon in placing him out to any trade, business or profession as they in their discretion shall think proper.

And I direct that to my said sons and daughters by my late wife and my said niece shall by wholly paid by my said reputed son Richard Moon out of the fortune herby given him. And it is my will and desire that my said reputed children shall deliver into the hands of my executors all the monies that shall arise from the carrying on of my business that is not wanted to carry on the same unto my acting executor and shall keep a just and true account of all disbursements and receipts of the said business and deliver up the same to my acting executor in order that there may not be any embezzlement or defraud amongst them and from and immediately after my said reputed youngest son Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years then I give, devise and bequeath all my real estate and all the residue and remainder of my personal estate of what nature and kind whatsoever and wheresoever unto and amongst all and every my said reputed sons and daughters namely William Moon, Thomas Moon, Joseph Moon, Richard Moon, Ann Moon, Margaret Moon and to my reputed daughter Mary Brearly to hold to them and their respective heirs, executors, administrator and assigns for ever according to the nature and tenure of the same estates respectively to take the same as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.And lastly I nominate and appoint the said Humphrey Trafford Nadin and John Wilkinson executors of this my last will and testament and guardians of all my reputed children who are under age during their respective minorities hereby revoking all former and other wills by me heretofore made and declaring this only to be my last will.

In witness whereof I the said Daniel Staley the testator have to this my last will and testament set my hand and seal the eleventh day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and five.

May 27, 2022 at 8:25 am #6300In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Carringtons

The Carringtons of Smalley, at least some of them, were Baptist ~ otherwise known as “non conformist”. Baptists don’t baptise at birth, believing it’s up to the person to choose when they are of an age to do so, although that appears to be fairly random in practice with small children being baptised. This makes it hard to find the birth dates registered as not every village had a Baptist church, and the baptisms would take place in another town. However some of the children were baptised in the village Anglican church as well, so they don’t seem to have been consistent. Perhaps at times a quick baptism locally for a sickly child was considered prudent, and preferable to no baptism at all. It’s impossible to know for sure and perhaps they were not strictly commited to a particular denomination.

Our Carrington’s start with Ellen Carrington who married William Housley in 1814. William Housley was previously married to Ellen’s older sister Mary Carrington. Ellen (born 1895 and baptised 1897) and her sister Nanny were baptised at nearby Ilkeston Baptist church but I haven’t found baptisms for Mary or siblings Richard and Francis. We know they were also children of William Carrington as he mentions them in his 1834 will. Son William was baptised at the local Smalley church in 1784, as was Thomas in 1896.

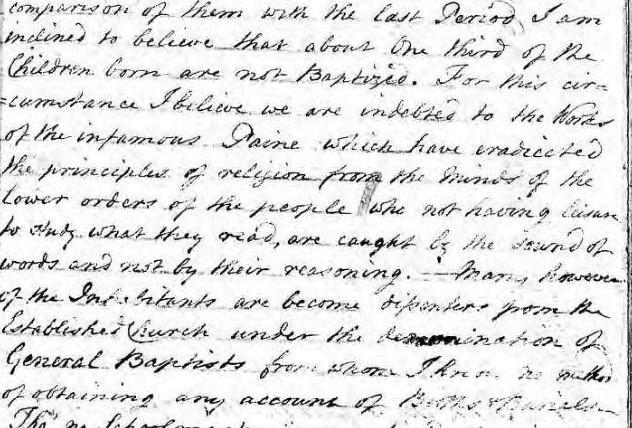

The absence of baptisms in Smalley with regard to Baptist influence was noted in the Smalley registers:

Smalley (chapelry of Morley) registers began in 1624, Morley registers began in 1540 with no obvious gaps in either. The gap with the missing registered baptisms would be 1786-1793. The Ilkeston Baptist register began in 1791. Information from the Smalley registers indicates that about a third of the children were not being baptised due to the Baptist influence.

William Housley son in law, daughter Mary Housley deceased, and daughter Eleanor (Ellen) Housley are all mentioned in William Housley’s 1834 will. On the marriage allegations and bonds for William Housley and Mary Carrington in 1806, her birth date is registered at 1787, her father William Carrington.

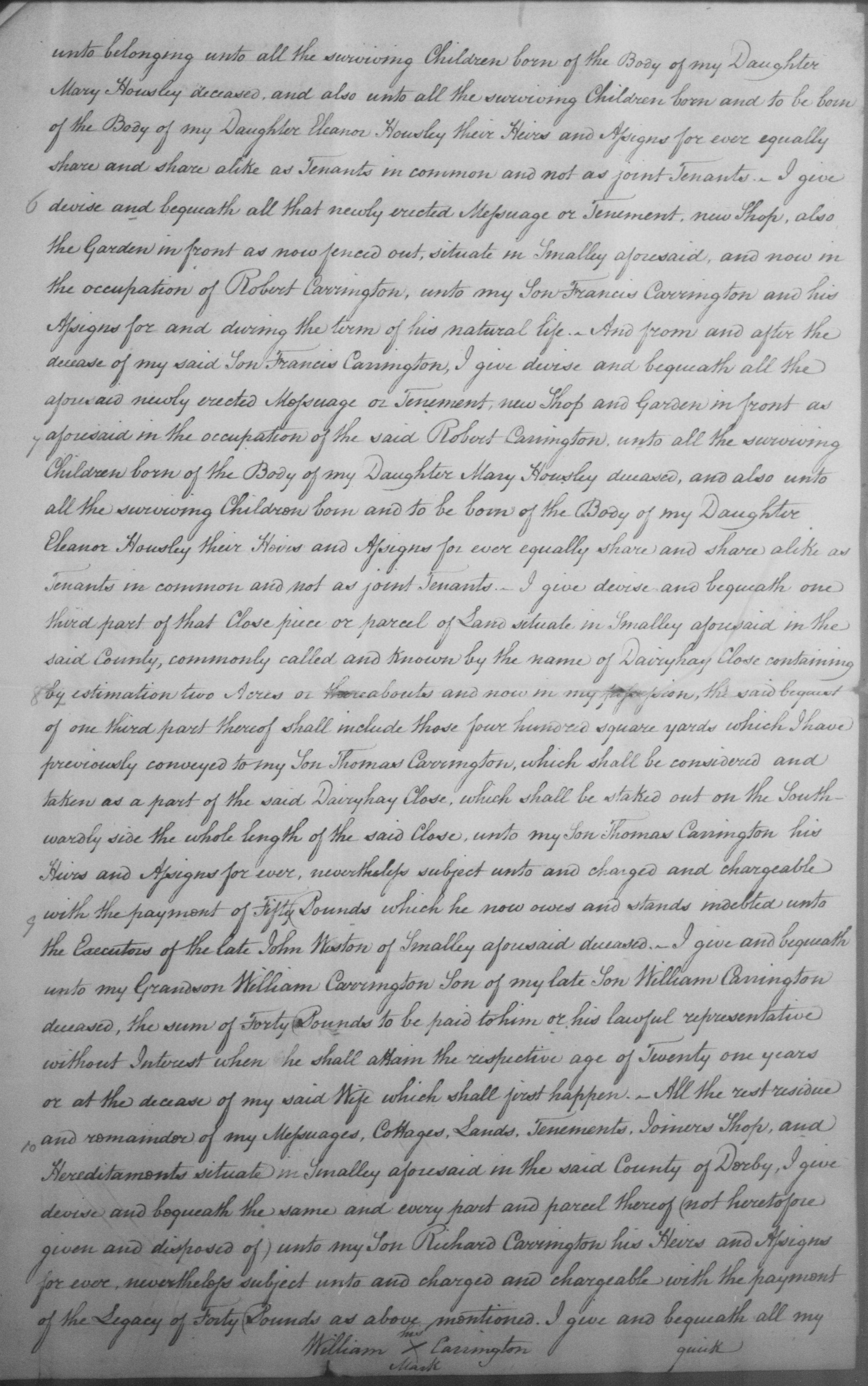

A Page from the will of William Carrington 1834:

William Carrington was baptised in nearby Horsley Woodhouse on 27 August 1758. His parents were William and Margaret Carrington “near the Hilltop”. He married Mary Malkin, also of Smalley, on the 27th August 1783.

When I started looking for Margaret Wright who married William Carrington the elder, I chanced upon the Smalley parish register micro fiche images wrongly labeled by the ancestry site as Longford. I subsequently found that the Derby Records office published a list of all the wrongly labeled Derbyshire towns that the ancestry site knew about for ten years at least but has not corrected!

Margaret Wright was baptised in Smalley (mislabeled as Longford although the register images clearly say Smalley!) on the 2nd March 1728. Her parents were John and Margaret Wright.

But I couldn’t find a birth or baptism anywhere for William Carrington. I found four sources for William and Margaret’s marriage and none of them suggested that William wasn’t local. On other public trees on ancestry sites, William’s father was Joshua Carrington from Chinley. Indeed, when doing a search for William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725, this was the only one in Derbyshire. But why would a teenager move to the other side of the county? It wasn’t uncommon to be apprenticed in neighbouring villages or towns, but Chinley didn’t seem right to me. It seemed to me that it had been selected on the other trees because it was the only easily found result for the search, and not because it was the right one.

I spent days reading every page of the microfiche images of the parish registers locally looking for Carringtons, any Carringtons at all in the area prior to 1720. Had there been none at all, then the possibility of William being the first Carrington in the area having moved there from elsewhere would have been more reasonable.

But there were many Carringtons in Heanor, a mile or so from Smalley, in the 1600s and early 1700s, although they were often spelled Carenton, sometimes Carrianton in the parish registers. The earliest Carrington I found in the area was Alice Carrington baptised in Ilkeston in 1602. It seemed obvious that William’s parents were local and not from Chinley.

The Heanor parish registers of the time were not very clearly written. The handwriting was bad and the spelling variable, depending I suppose on what the name sounded like to the person writing in the registers at the time as the majority of the people were probably illiterate. The registers are also in a generally poor condition.

I found a burial of a child called William on the 16th January 1721, whose father was William Carenton of “Losko” (Loscoe is a nearby village also part of Heanor at that time). This looked promising! If a child died, a later born child would be given the same name. This was very common: in a couple of cases I’ve found three deceased infants with the same first name until a fourth one named the same survived. It seemed very likely that a subsequent son would be named William and he would be the William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725 that we were looking for.

Heanor parish registers: William son of William Carenton of Losko buried January 19th 1721:

The Heanor parish registers between 1720 and 1729 are in many places illegible, however there are a couple of possibilities that could be the baptism of William in 1724 and 1725. A William son of William Carenton of Loscoe was buried in Jan 1721. In 1722 a Willian son of William Carenton (transcribed Tarenton) of Loscoe was buried. A subsequent son called William is likely. On 15 Oct 1724 a William son of William and Eliz (last name indecipherable) of Loscoe was baptised. A Mary, daughter of William Carrianton of Loscoe, was baptised in 1727.

I propose that William Carringtons was born in Loscoe and baptised in Heanor in 1724: if not 1724 then I would assume his baptism is one of the illegible or indecipherable entires within those few years. This falls short of absolute documented proof of course, but it makes sense to me.

In any case, if a William Carrington child died in Heanor in 1721 which we do have documented proof of, it further dismisses the case for William having arrived for no discernable reason from Chinley.

May 3, 2022 at 4:40 pm #6291In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Jane Eaton

The Nottingham Girl

Jane Eaton 1809-1879

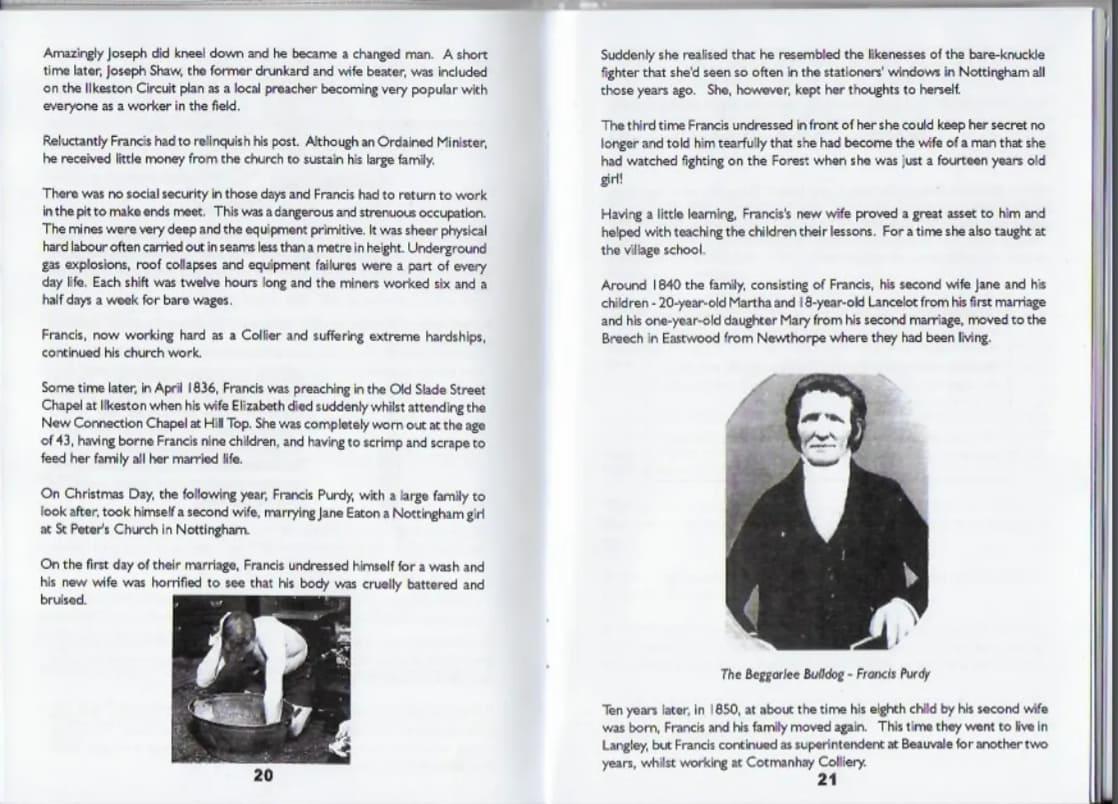

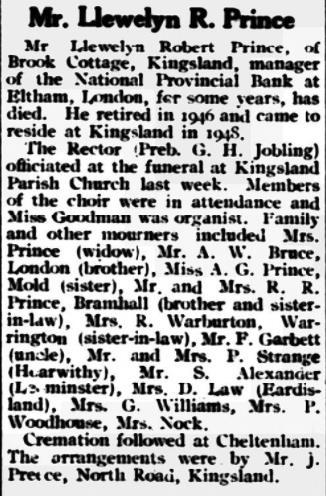

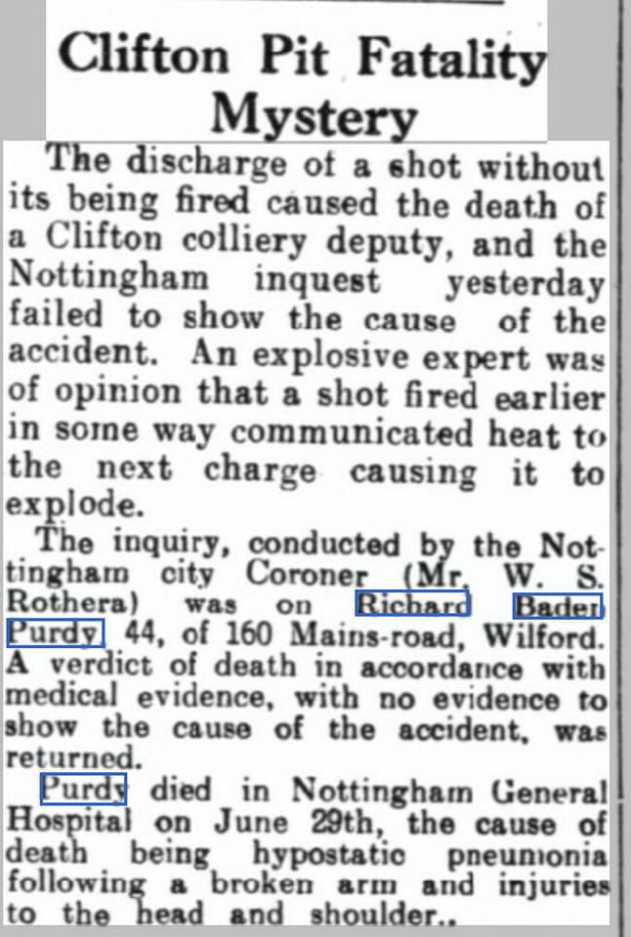

Francis Purdy, the Beggarlea Bulldog and Methodist Minister, married Jane Eaton in 1837 in Nottingham. Jane was his second wife.

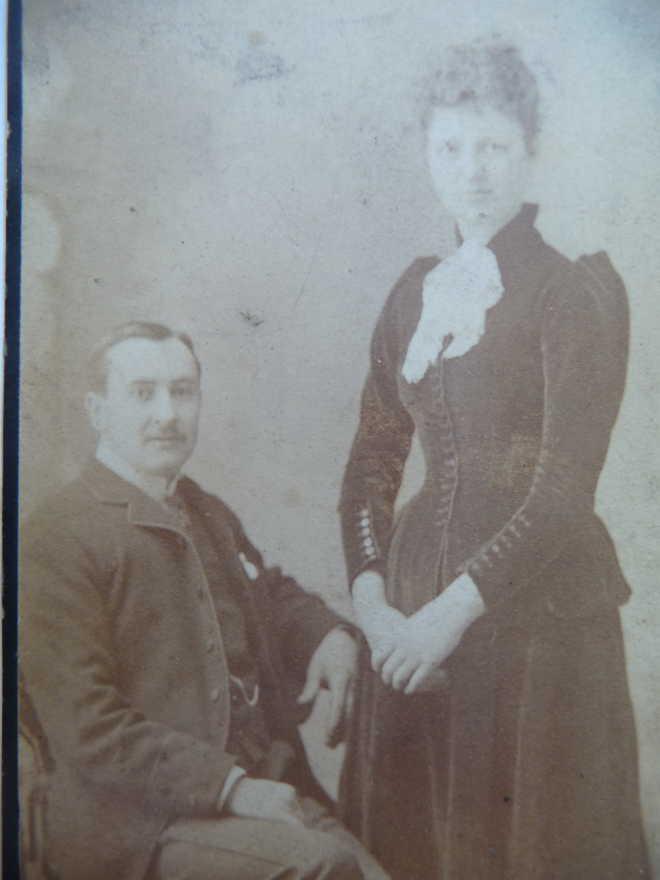

Jane Eaton, photo says “Grandma Purdy” on the back:

Jane is described as a “Nottingham girl” in a book excerpt sent to me by Jim Giles, a relation who shares the same 3x great grandparents, Francis and Jane Purdy.

Elizabeth, Francis Purdy’s first wife, died suddenly at chapel in 1836, leaving nine children.

On Christmas day the following year Francis married Jane Eaton at St Peters church in Nottingham. Jane married a Methodist Minister, and didn’t realize she married the bare knuckle fighter she’d seen when she was fourteen until he undressed and she saw his scars.

William Eaton 1767-1851

On the marriage certificate Jane’s father was William Eaton, occupation gardener. Francis’s father was William Purdy, engineer.

On the 1841 census living in Sollory’s Yard, Nottingham St Mary, William Eaton was a 70 year old gardener. It doesn’t say which county he was born in but indicates that it was not Nottinghamshire. Living with him were Mary Eaton, milliner, age 35, Mary Eaton, milliner, 15, and Elizabeth Rhodes age 35, a sempstress (another word for seamstress). The three women were born in Nottinghamshire.

But who was Elizabeth Rhodes?

Elizabeth Eaton was Jane’s older sister, born in 1797 in Nottingham. She married William Rhodes, a private in the 5th Dragoon Guards, in Leeds in October 1815.

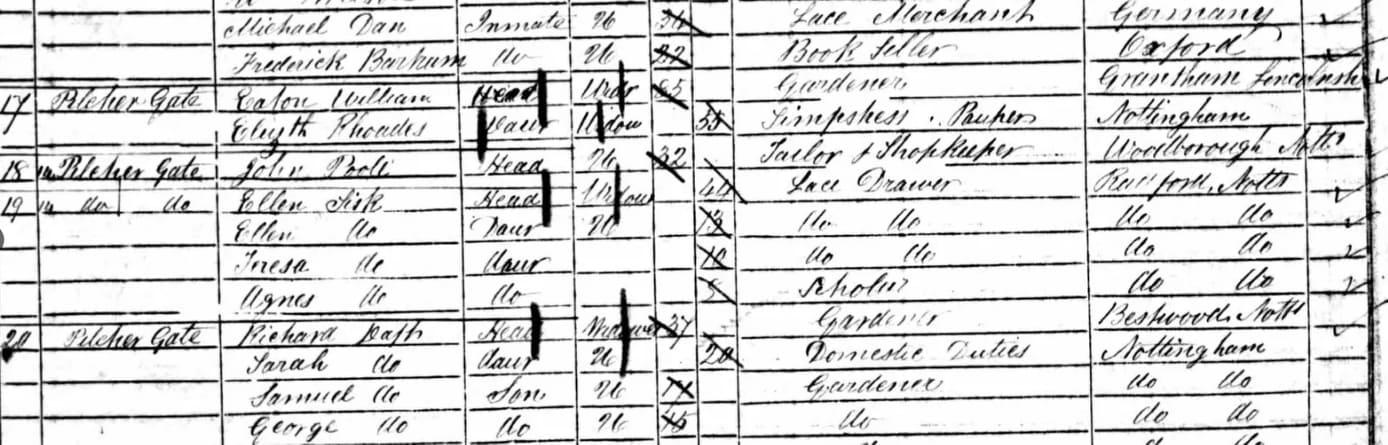

I looked for Elizabeth Rhodes on the 1851 census, which stated that she was a widow. I was also trying to determine which William Eaton death was the right one, and found William Eaton was still living with Elizabeth in 1851 at Pilcher Gate in Nottingham, but his name had been entered backwards: Eaton William. I would not have found him on the 1851 census had I searched for Eaton as a last name.

Pilcher Gate gets its strange name from pilchers or fur dealers and was once a very narrow thoroughfare. At the lower end stood a pub called The Windmill – frequented by the notorious robber and murderer Charlie Peace.

This was a lucky find indeed, because William’s place of birth was listed as Grantham, Lincolnshire. There were a couple of other William Eaton’s born at the same time, both near to Nottingham. It was tricky to work out which was the right one, but as it turned out, neither of them were.

Now we had Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire border straddlers, so the search moved to the Lincolnshire records.

But first, what of the two Mary Eatons living with William?William and his wife Mary had a daughter Mary in 1799 who died in 1801, and another daughter Mary Ann born in 1803. (It was common to name children after a previous infant who had died.) It seems that Mary Ann didn’t marry but had a daughter Mary Eaton born in 1822.

William and his wife Mary also had a son Richard Eaton born in 1801 in Nottingham.

Who was William Eaton’s wife Mary?

There are two possibilities: Mary Cresswell and a marriage in Nottingham in 1797, or Mary Dewey and a marriage at Grantham in 1795. If it’s Mary Cresswell, the first child Elizabeth would have been born just four or five months after the wedding. (This was far from unusual). However, no births in Grantham, or in Nottingham, were recorded for William and Mary in between 1795 and 1797.

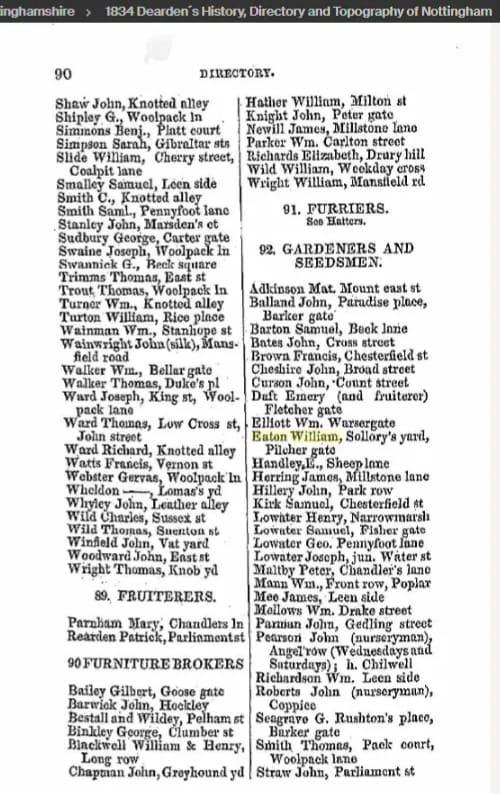

We don’t know why William moved from Grantham to Nottingham or when he moved there. According to Dearden’s 1834 Nottingham directory, William Eaton was a “Gardener and Seedsman”.

There was another William Eaton selling turnip seeds in the same part of Nottingham. At first I thought it must be the same William, but apparently not, as that William Eaton is recorded as a victualler, born in Ruddington. The turnip seeds were advertised in 1847 as being obtainable from William Eaton at the Reindeer Inn, Wheeler Gate. Perhaps he was related.