Search Results for 'pages'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

October 25, 2023 at 7:08 am #7282

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Ellastone Gerrards in the 1500s.

John Gerrard 1633-1681 was born and died in Ellastone.

Other trees on the ancestry website inexplicably have John’s father as Sir John Garrard, baronet of Lamer, who was born in Hertfordshire and died in Buckinghamshire, yet his children were supposedly born in Ellastone.

Fortunately the Ellastone parish records begin in 1537. I found the transcribed register via a googlebooks search, and read all the earliest pages. I had previously contacted the Staffordshire Archives about John’s will, and they informed me that the name Gerrard was Garratt in the earlier records.

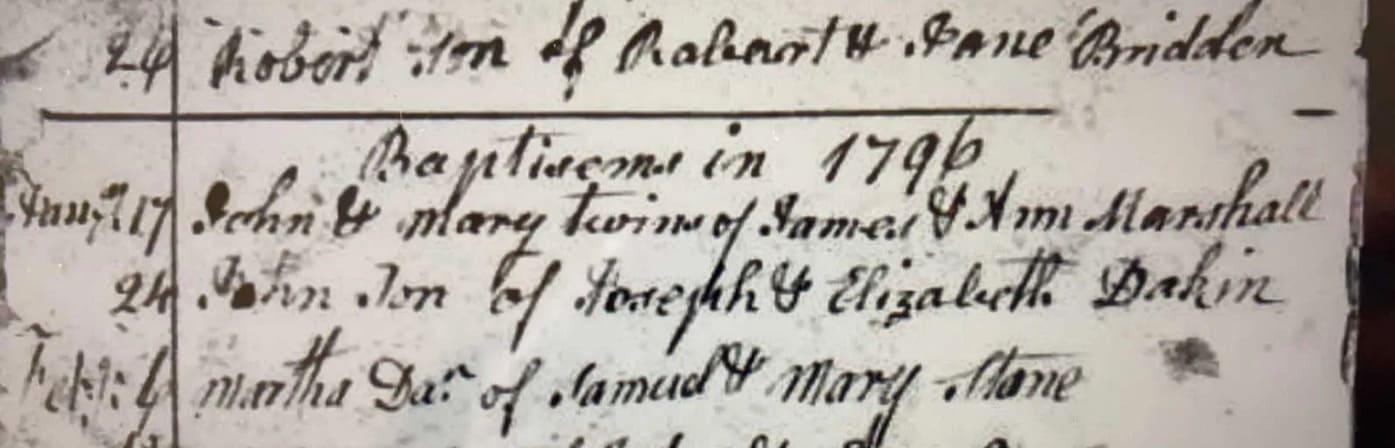

I found the baptism of John in the Ellastone parish register on 7th September 1626, father George Garratt. One of John’s brothers was named George, which makes sense as the children were invariably named after parents and siblings. However, John born in 1626 died in 1628. Another son named John was baptised in 1633.

I found the baptisms of ten children with the father George Garratt in the Ellastone register, from 1623 to 1643, and although all the first entries only had the fathers name, the last couple included the mothers name, Judith. George Garratt was a churchwarden in Ellastone in 1627.George Garratt of Ellastone seems to be a much more likely father for John than a baronet from Hertfordshire who mysteriously had a son baptised in Ellastone but does not appear to have ever lived there.

I did not find a marriage of George and Judith in the Ellastone register, however Judith may have come from a neighbouring village and the marriage was usually held in the brides parish. The wedding was probably circa 1622.

George was baptised in Ellastone on the 19th March 1595. Some of the transcriptions say March 1794, some say 1795. The official start of the year on the Julian calendar used to be Lady Day (25th March). This was changed in 1752.

His father was Rycharde Garrarde. Rycharde married Agnes Bothom in Ellastone on the 29th September 1594. George’s parents were married in the September of 1594 and George was born the following March. On the old calendar, March came after September.

George died in 1669 in Ellastone. He was my 10X great grandfather. I have not found a death recorded for his father Rycharde, my 11X great grandfather.

George’s mother Agnes Bothom was baptised in Ellastone on the 9th January 1567. Her father was John Bothom. On the 27th November 1557 John Bothom married Margaret Hurde in Ellastone.

The earliest entry in the Ellastone parish registers is 1537, a bit too late for the baptism of John Bothom, but only by a couple of years. John Bothom and his wife Agnes were probably born around 1535. Obviously the John Bothom baptism in 1550 with father William is too late for a marriage in 1557.

March 24, 2023 at 7:49 am #7214In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“Bossy, isn’t she?” muttered Yasmin, not quite out of earshot of Finly. “I haven’t even had a shower yet,” she added, picking up her phone and sandals.

Yasmin, Youssef and Zara left the maid to her cleaning and walked down towards Xaviers room. “I’d go and get coffee from the kitchen, but…” Youssef said, turning pleading eyes towards Zara, “Idle might be in there.”

Smiling, Zara told him not to risk it, she would go.

“Come in,” Xavier called when Yasmin knocked on the door. “God, what a dream,” he said when they piled in to his room. “It was awful. I was dreaming that Idle was threading an enormous long needle with baler twine saying she was going to sew us all together in a tailored story cut in a cloth of continuity.” He rubbed his eyes and then shook his head, trying to erase the image in his mind. “What are you two up so early for?”

“Zara’s gone to get the coffee,” Youssef told him, likewise trying to shake off the image of Idle that Xavier had conjured up. “We’re going to have a couple of hours on the game before the cart race ~ or the dust storm, whichever happens first I guess. There are some wierd looking vans and campers and oddballs milling around outside already.”

Zara pushed the door open with her shoulder, four mugs in her hands. “You should see the wierdos outside, going to be a great photo opportunity out there later.”

“Come on then,” said Xavier, “The game will get that awful dream out of my head. Let’s go!”

“You’re supposed to be the leader, you start the game,” Yasmin said to Zara. Zara rolled her eyes good naturedly and opened the game. “Let’s ask for some clues first then. I still don’t know why I’m the so called leader when you,” she looked pointedly as Xavier and Youssef, “Know much more about games than I do. Ok here goes:”

“The riddle “In the quietest place, the loudest secrets are kept” is a clue to help the group find the first missing page of the book “The Lost Pages of Creativity,” which is an integral part of the group quest. The riddle suggests that the missing page is hidden in a quiet place where secrets are kept, meaning that it’s likely to be somewhere in the hidden library underground the Flying Fish Inn where the group is currently situated.”

“Is there a cellar here do you think?” Zara mused. “Imagine finding a real underground library!” The idea of a grand all encompassing library had first been suggested to Zara many years ago in a series of old books by a channeler, and many a time she had imagined visiting it. The idea of leaving paper records and books for future generations had always appealed to her. She often thought of the old sepia portrait photographs of her ancestors, still intact after a hundred years ~ and yet her own photos taken ten years ago had been lost in a computer hard drive incident. What would the current generation leave for future anthropologists? Piles of plastic unreadable gadgets, she suspected.

“Youssef can ask Idle later,” Xavier said with a cheeky grin. “Maybe she’ll take him down there.” Youssef snorted, and Yasmin said “Hey! Don’t you start snorting too! Right then, Zara, so we find the cellar in the game then and go down and find the library? Then what?”

“The phrase “quietest place” can refer to a secluded spot or a place with minimal noise, which could be a hint at a specific location within the library. The phrase “loudest secrets” implies that there is something important to be discovered, but it’s hidden in plain sight.”

Hidden in plain sight reminded Yasmin of the parcel under her mattress, but she thrust it from her mind and focused on the game. She made up her mind to discuss it with everyone later, including the whacky suppositions that Zara had come up with. They couldn’t possibly confront Idle with it, they had absolutely no proof. I mean, you can’t go round saying to people, hey, that’s your abandoned child over there maybe. But they could include Xavier and Youssef in the mystery.

“The riddle is relevant to the game of quirks because it challenges the group to think creatively and work together to solve the puzzle. This requires them to communicate effectively and use their problem-solving skills to interpret the clues and find the missing page. It’s an opportunity to demonstrate their individual strengths and also learn from each other in the process.”

“Work together, communicate effectively” Yasmin repeated, as if to underline her resolution to discuss the parcel and Sister Finli a.k.a. Liana with the boys and Zara later. “A problem shared is a problem hopelessly convoluted, probably.”

The others looked up and said “What?” in unison, and Yasmin snorted nervously and said “Never mind, tell you later.”

March 9, 2023 at 3:49 am #6793In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Finnley had promised Liz she would polish at least one window this afternoon, and, if nothing else, she was a person of her word. It’s a gesture of goodwill, as it were, she thought smugly.

“Window polished,” she said after a few minutes of haphazardly flinging a cloth at the glass. She stood back to admire her handiwork and accidentally stepped on Godfrey who was buried under piles of pages and muttering something about Liz’s genius.

“That’s one word for it I suppose,” she hissed at him. “Another word is DRUGS. Now, if you will excuse me, I have to go to my room and think.” She aimed a particularly vigorous eye roll in Godfrey’s direction. “Wherever I am, I am one with the clouds and one with the sun and the stars you see.”

“You don’t have time to think!” screamed Liz, jumping up from behind the sofa where she had been privately relishing Godfrey’s musings about her genius.

February 28, 2023 at 1:14 pm #6720In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“It’s amazing, all the material we gathered over the years, it makes one’s head spin…” Godfrey was poring over quantities of papers, mostly early drafts stuck haphazardly in a pile of donations boxes that Elizabeth had generously contributed to the National Library’s archives of great works and renowned authors, but mostly as way of spring cleaning.

He had materialized some of the links from the pages with webs of purple yarn tied to the wall of the dining hall. It had soon become a tangled mess of interwoven threads that he had to protect from the cleaning frenzied assaults of energetic feather duster of Finnley.

She’d softened her stance a little when she’s realised how often her namesake has popped in the various storylines, almost making her emotional about Liz’ incorporating her in her works of fictions —only to remember that most of the time, she’d been the working hand behind the continuity, the Finnleys appearances being an offshoot of this endeavour.

Godfrey had almost forgotten he was actually a publisher to start with, before he became more of a useful side-kick, if not a useful idiot.

The phone rang in the empty hall. Soon after, Finnley arrived with the heavy bakelite telephone, handing it over to Godfrey unceremoniously. “You might want to take this, it’s Felicity…” she mouthed the last word like it was the name of the Devil himself.

“Dear Flove protect us, don’t tell me Liz’ mother is in town…”

“Well, at least she has comic relief value” snorted Finnley on her way back to her duties.

February 26, 2023 at 10:29 pm #6709Topic: Storylines & Complements

in forum The Faded Cabbage TavernStorylines

You may have noticed it – the little purple tags next to your comments are linking them to particular storylines.

It should help reconnect comments spread across threads, when they belong to a particular storyline. The definition of those is rather fluid, but in general, it tends to revolve about a commonality of protagonist or group of protagonists (they are easy to spot, they are the one(s) driving the storyline plot forward…

).

).Since the tagging is mostly manual, and there are quite a few homonymous characters, you may still find comments that shouldn’t belong in the storyline. It will take some time to clean.

Of course, some comments do belong to multiple storylines, particularly when there are some cross-overs (e.g. protagonists from the Pop*in story going to the Flying Fish Inn, and meeting Arona!)

New feature: Complement Storylines

This new feature is now available ; basically, it should allow you to continue (or insert) on a storyline, especially those long gone… For the storylines that already have their own distinct threads, you don’t need really the feature but you can also use it.

How to do?

You can go to a storyline, let’s say… Dead Dick Tracy, Peaslander, etc.

If you find a particular storyline you like that is missing (I guess nobody regrets the Tw’Elves,… but who knows?

)

)You normally will see a little link with the replies.

COMPLEMENT.

Let’s say you just want to continue the story. You go the last comment, and you click on the

COMPLEMENTlink of the last comment.Normally, if you got there, the hardest remains to do: write a comment.

If all goes well, it’ll be posted in the New found pages thread, a little bit like old time “Circle of Eights” single thread full of unrelated comments, but this time, each one will have a little purple “storyline” tag, that will make it available inside the storyline you selected… February 25, 2023 at 3:25 pm #6689

February 25, 2023 at 3:25 pm #6689Topic: Stories: New Found Pages

in forum Yurara Fameliki’s StoriesThis is a special thread.

Although closed, it is open

if you can find the door.Although messy, it is full of connections

if you peer through the weft, follow the right thread.February 23, 2023 at 7:43 am #6634In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

The next quest is going to be a group quest for Zara, Yasmin, Xavier and Youssef. It will require active support and close collaboration to focus on a single mystery at first not necessarily showing connection or interest to all members of the group, but completing it will show how all things are interconnected. It may start inside the game at the hidden library underground the Flying Fish Inn.

Quirk offered for this: getting lost in the mines of creativity, and struggle to complete the chapters of the book of Story to a satisfactory conclusion.

Quirk accepted.

The group finds themselves in the hidden library underground the Flying Fish Inn, surrounded by books and manuscripts. They come across a particularly old and mysterious book titled “The Lost Pages of Creativity.” The book contains scattered chapters, each written by a different author, but the group soon realizes that they are all interconnected and must be completed in order to unlock the mystery of the book’s true purpose.

Each chapter presents a different challenge related to creativity, ranging from writing a poem to creating a piece of art. The group must work together to solve each challenge, bringing their individual skills and perspectives to the table. As they complete each chapter, they will uncover clues that lead them deeper into the mystery.

Their ultimate goal is to find the missing pages of the book, which are scattered throughout the inn and surrounding areas. They will need to use their problem-solving skills and work together to find and piece together the missing pages in the correct order to unlock the true purpose of the book.

To begin, the group is given a clue to start their search for the first missing page: “In the quietest place, the loudest secrets are kept.” They must work together to decipher the clue and find the missing page. Once found, they must insert the corresponding tile into the game to progress to the next chapter. Proof of the insert should be provided in real life.

Each of the four characters are provided with a personal clue:

Zara: “Amidst the foliage and bark, A feather and a beak in the dark 🌳🍃🐦🕯️🌑”

Yasmin: “In the depths of the ocean blue, A key lies waiting just for you 🌊🔑🧜♀️🐚🕰️”

Xavier: “Seeking knowledge both new and old, Find the owl with eyes of gold 📚🦉💡🔍🕰️”

Youssef: “Amongst the sands and rocky dunes, A lantern flickers, a key it looms 🏜️🪔🔍🔑🕯️”

Each of these clues hints at a specific location or object that the character needs to find in order to progress in the game.

February 14, 2023 at 8:48 pm #6545In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The road was stretching endlessly and monotonously, a straight line disappearing into a nothingness of dry landscapes that reminded Youssef of the Gobi desert where he had been driving not too long ago. At regular speed, the car barely seemed to progress.

> O Time suspend thy flight!

Eternity. Something only nature could procure him. He loved the feeling, and compared to the more usual sand of Gobi, the red sands of Australia gave him the impression he had shifted into another reality. That and the fifteen hours flight listening to Gladys made it difficult to respond to Xavier’s loquacious self and funny jokes. After some time, his friend stopped talking and tried catching some signal to play the Game, brandishing his phone in different directions as if he was hunting ghosts with a strange device.

It reminded him he had to accept his next quest in a ghost town. That’s all he remembered. He could do that at the Inn, when they could rest in their rooms.

Youssef wondered if the welcome sign at the entrance of the town had seen better days. The wood the fish was made of seemed eaten by termites, but someone had painted it with silver and blue to give it a fresher look. Youssef snorted at the shocked expression on his friend’s face.

“It looked like it died of boredom. Let’s just hope the Innside doesn’t look like a gutted fish,” Xavier said.

An old lady showed them their rooms. She didn’t seem the talkative type, which made Youssef love her immediately with her sharp tongue and red cardigan. He rather admired her braided silver hair as it reminded him of his mother who would let him brush her hair when they lived in Norway. It was in another reality. He smiled. She saw him looking at her and her eyes narrowed like a pair of arrowslits. She seemed ready to fire. Instead she kept on ranting about an idle person not doing her only job properly. They each went to their rooms, Xavier took number 7 and Youssef picked number 5, his lucky number.

He was glad to be able to enjoy his own room after the trip of the last few weeks. It had been for work, so it was different. But usually he liked travelling the world on his own and meet people on his way and learn from their stories. Traveling with people always meant some compromise that would always frustrate him because he wanted to go faster, or explore more tricky paths.

The room was nicely decorated, and the scent of fresh paint made it clear it was recent. A strange black stone, which Youssef recognized as a black obsidian, has been put on a pile of paper full of doodles, beside two notebooks and pencils. The notebooks’ pages were blank, he thought of giving them to Xavier. He took the stone. It was cold to the touch and his reflection on the surface looked back at him, all wavy. The doodles on the paper looked like a map and hard to read annotations. One stood out, though which looked like a wifi password. That made him think of the Game. He entered it on his phone and that was it. Maybe it was time to go back in. But he wanted to take a shower first.

He put his backpack and his bag on the bed and unpacked it. Amongst a pile of dirty clothes, he managed to find a t-shirt that didn’t smell too bad and a pair of shorts. He would have to use the laundry service of the hotel.

He had missed hot showers. Once refreshed, he moved his bags on the floor and jumped on his bed and launched the Game.

Youssef finds himself in a small ghost town in what looks like the middle of the Australian outback. The town was once thriving but now only a few stragglers remain, living in old, decrepit buildings. He’s standing in the town square, surrounded by an old post office, a saloon, and a few other ramshackle buildings.

Youssef finds himself in a small ghost town in what looks like the middle of the Australian outback. The town was once thriving but now only a few stragglers remain, living in old, decrepit buildings. He’s standing in the town square, surrounded by an old post office, a saloon, and a few other ramshackle buildings.A message appeared on the screen.

Quest: Your task is to find the source of the magnetic pull that attracts talkative people to you. You must find the reason behind it and break the spell, so you can continue your journey in peace.

Youssef started to move his avatar towards the saloon when someone knocked on the door.

February 9, 2023 at 7:59 pm #6518In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Xavier had been drowsing in the rental car for a while, waiting for a message from Youssef. He’d stopped the aircon despite the suffocating heat, as he was starting to feel cold. And he’d started to nose dive in dreaming.

The buzzing of his phone made him snap back to consciousness from the weirdest dream, he had to take a few seconds to adjust. The phone went into silent mode to voicemail before he got the chance to pick it up.

Weirdest dream ever. Few hours ago, he’d been going round and round the place, trying to find a library to buy a black book, but surprisingly, even when he’d managed to find a small bookstore, there were none to sell. None with a black cover…

He’d wondered —sometimes these quests are made to be difficult, but come on, how difficult could it be. Even a plain black-covered notebook would have been enough, but nothing!

That’s when he’d decided to drop the search, that he dozed off in the car.

Few images came back from the dream. First, the insane search, and books coming up in all shapes and forms, any color but black… or black but with black-and-white photos on the covers he didn’t want.

And then, there was one. He started to open it, and all the pages were blank. As he was browsing them, looking for a clue, like a pop-out book, something came up from the middle of the pages. And it was himself, smiling back at him. The shock snapped him right back to the rather quiet street of Alice Springs.

SOOO WEIIIIRD

He turned the ignition back on as well as the aircon. Checked his message.

- 📨

[Quirk Land] NEW QUEST OPENED - ➿

1 voicemail from ❣️🐝Brytta🐝❣️ - 💬 Youssef typing…

January 11, 2023 at 10:32 pm #6368In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Something in the style of FPooh:

Arona heard the music growing louder as she approached the source of the sound. She could see a group of people gathered around a large fire, the flickering light casting shadows on the faces of the dancers. She hesitated for a moment, remembering the isolation of her journey and wondering if she was ready to be among people again. But the music was too inviting, and she found herself drawn towards the group.

As she neared the fire, she saw a young man playing a flute, the music flowing from his fingers with a fluid grace that captivated her. He looked up as she approached, and their eyes met. She could see the surprise and curiosity in his gaze, and she smiled, feeling a sense of connection she had not felt in a long time.

Fiona was sitting on a bench in the park, watching the children play. She had brought her sketchbook with her, but for once she didn’t feel the urge to draw. Instead she watched the children’s laughter, feeling content and at peace. Suddenly, she saw a young girl running towards her, a look of pure joy on her face. The girl stopped in front of her and held out a flower, offering it to Fiona with a smile.

Taken aback, Fiona took the flower and thanked the girl. The girl giggled and ran off to join her friends. Fiona looked down at the flower in her hand, and she felt a sense of inspiration, like a spark igniting within her. She opened her sketchbook and began to draw, feeling the weight lift from her shoulders and the magic of creativity flowing through her.

Minky led the group of misfits towards the emporium, his bowler hat bobbing on his head. He chattered excitedly, telling stories of the wondrous items to be found within Mr Jib’s store. Yikesy followed behind, still lost in his thoughts of Arona and feeling a sense of dread at the thought of buying a bowler hat. The green fairy flitted along beside him, her wings a blur of movement as she chattered with the parrot perched on her shoulder.

As they reached the emporium, they were disappointed to find it closed. But Minky refused to be discouraged, and he led them to a nearby cafe where they could sit and enjoy some tea and cake while they wait for the emporium to open. The green fairy was delighted, and she ordered a plate of macarons, smiling as she tasted the sweetness of the confections.

About creativity & everyday magic

Fiona had always been drawn to the magic of creativity, the way a blank page could be transformed into a world of wonder and beauty. But lately, she had been feeling stuck, unable to find the spark that ignited her imagination. She would sit with her sketchbook, pencil in hand, and nothing would come to her.

She started to question her abilities, wondering if she had lost the magic of her art. She spent long hours staring at her blank pages, feeling a weight on her chest that seemed to be growing heavier every day.

But then she remembered the green fairy’s tears and Yikesy’s longing for Arona, and she realized that the magic of creativity wasn’t something that could be found only in art. It was all around her, in the everyday moments of life.

She started to look for the magic in the small things, like the way the sunlight filtered through the trees, or the way a child’s laughter could light up a room. She found it in the way a stranger’s smile could lift her spirits, and in the way a simple cup of tea could bring her comfort.

And as she started to see the magic in the everyday, she found that the weight on her chest lifted and the spark of inspiration returned. She picked up her pencil and began to draw, feeling the magic flowing through her once again.

She understand that creativity blocks aren’t a destination, but just a step, just like the bowler hat that Minky had bought for them all, a bit of everyday magic, nothing too fancy but a sense of belonging, a sense of who they are and where they are going. And she let her pencil flow, with the hopes that one day, they will all find their way home.

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

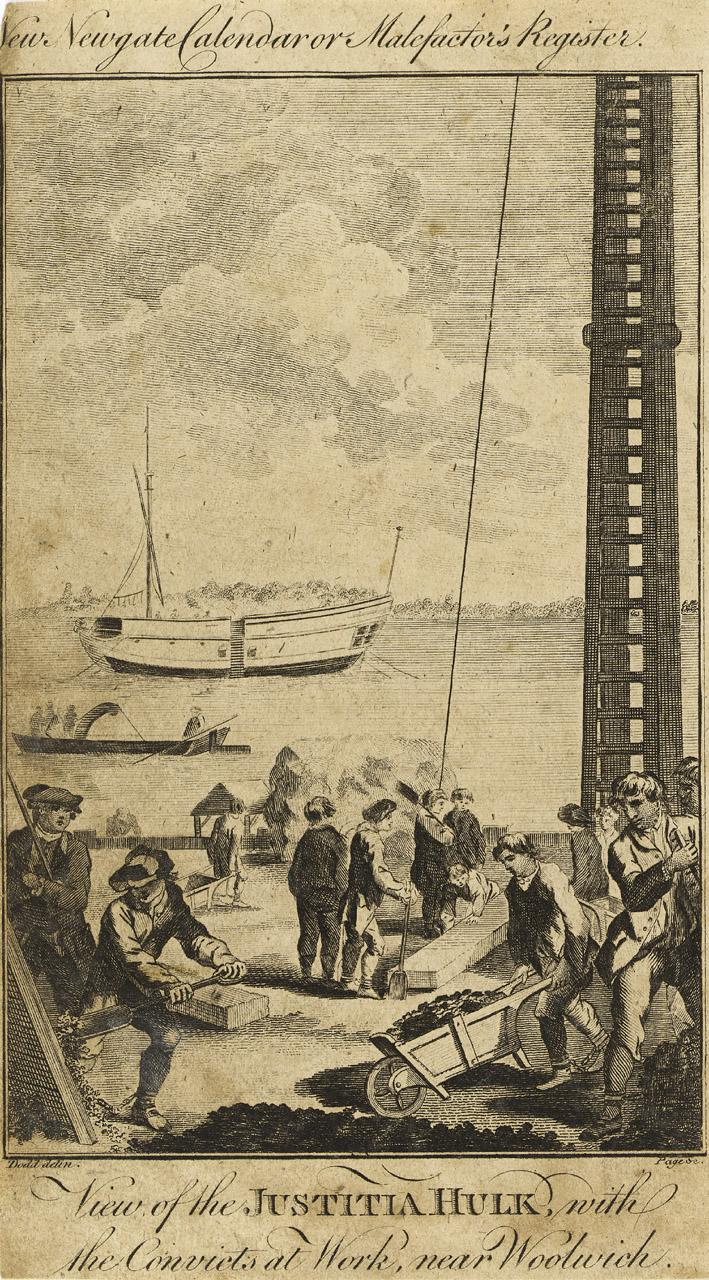

Transportation

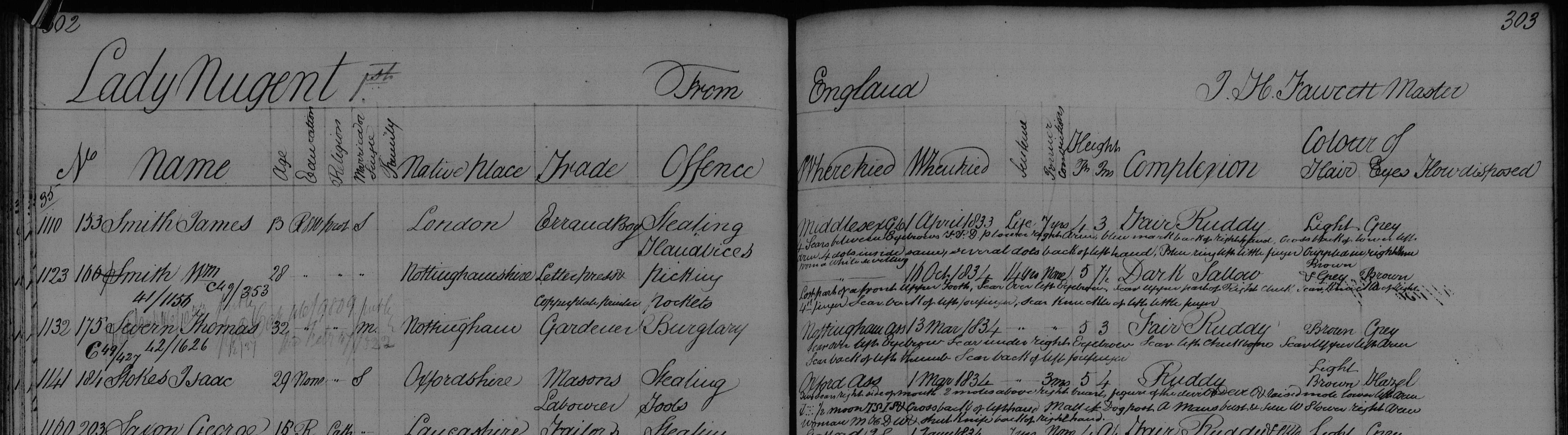

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

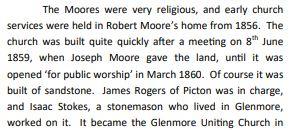

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

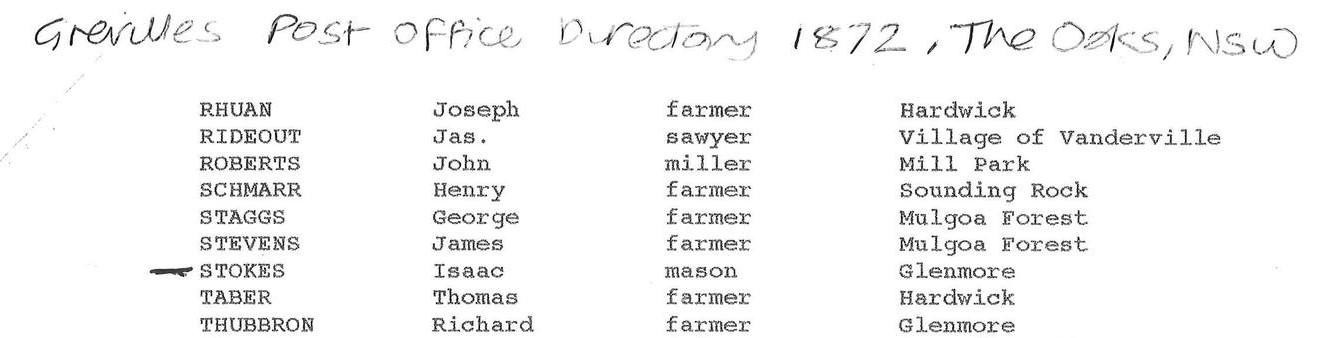

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306

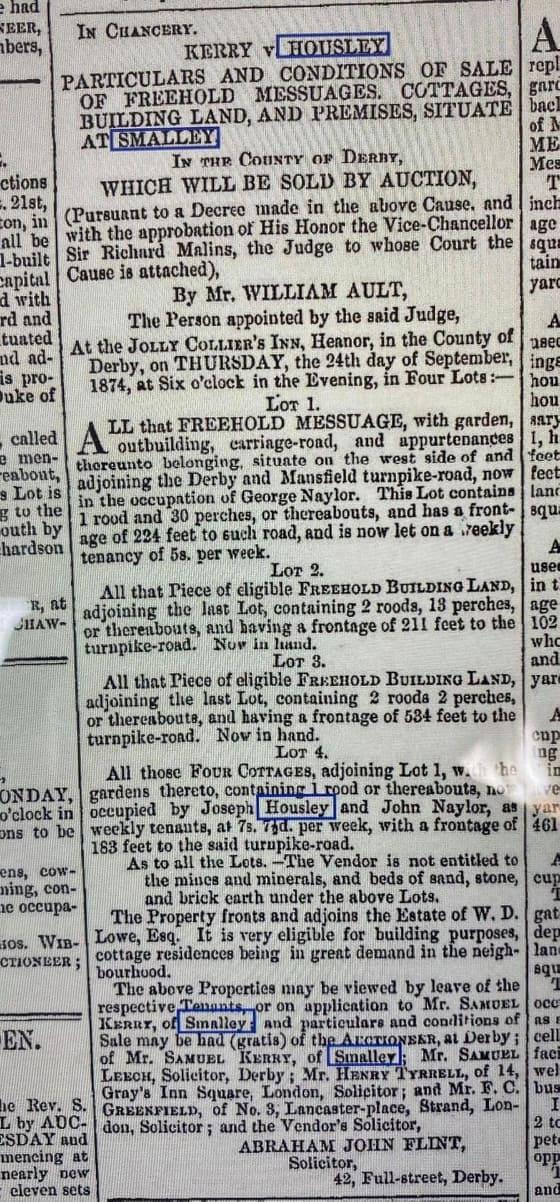

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

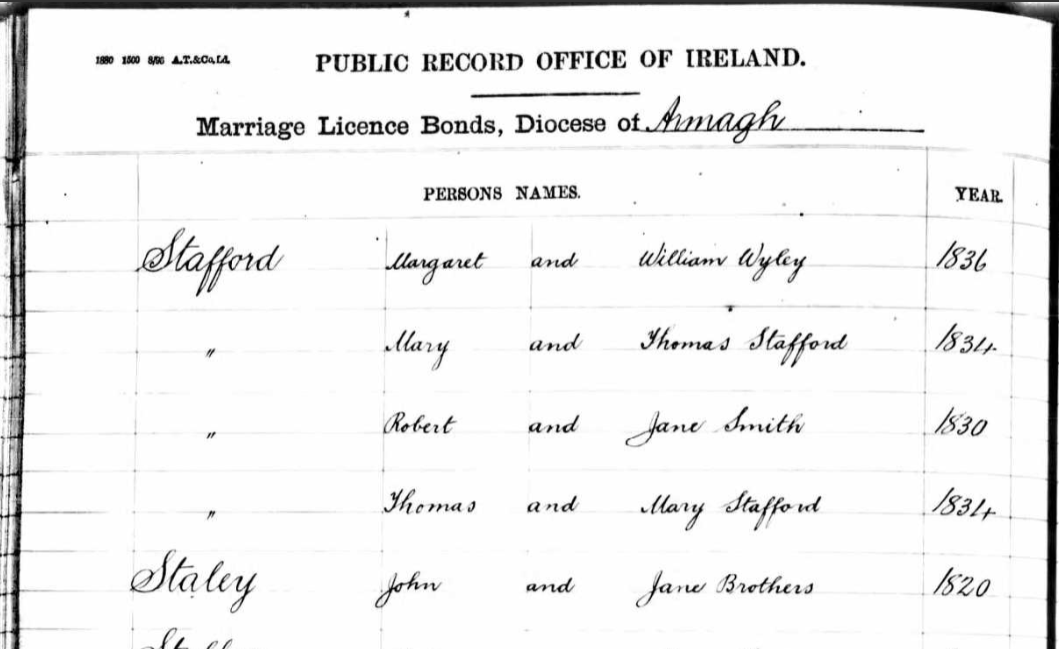

Looking for Robert Staley

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

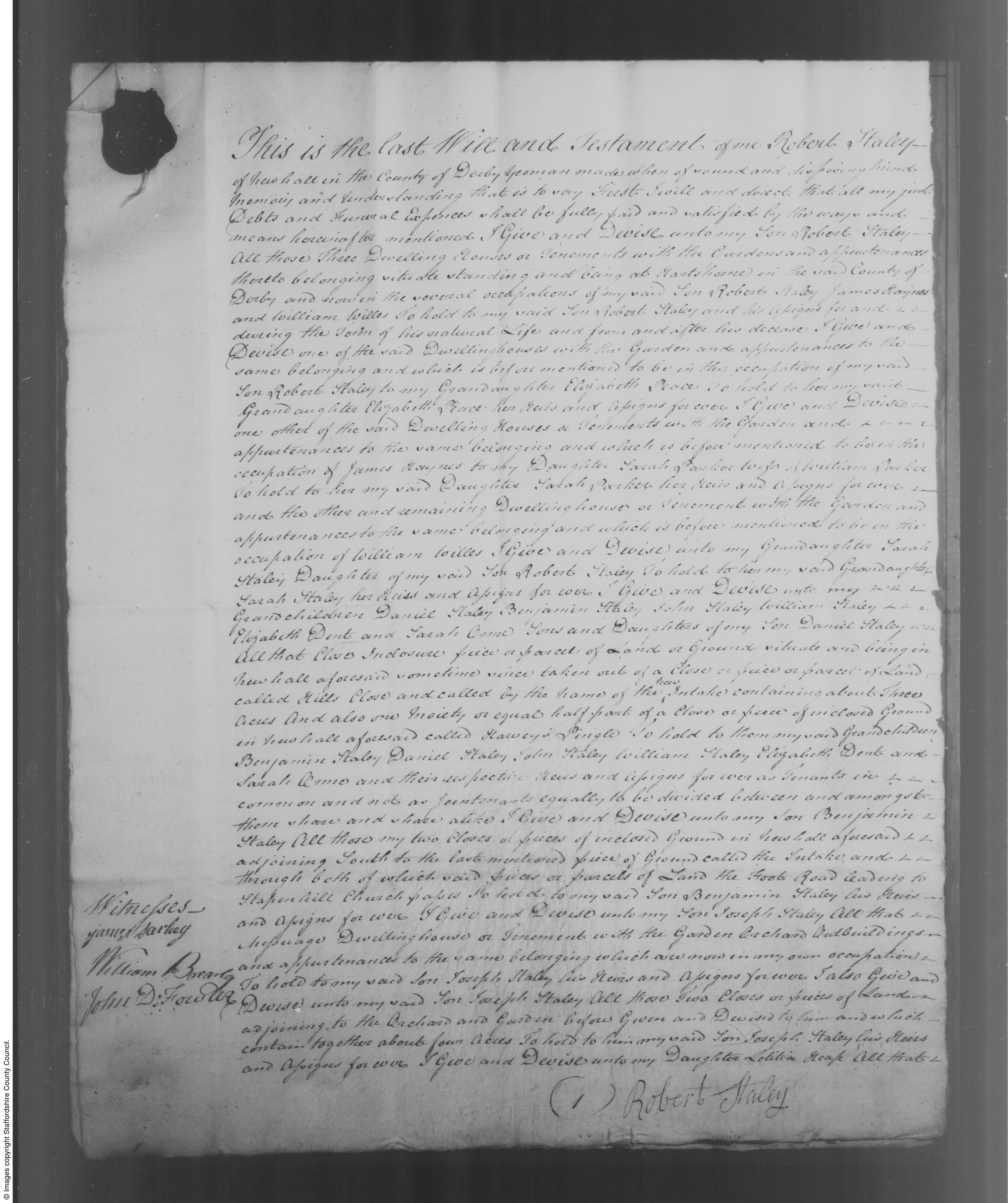

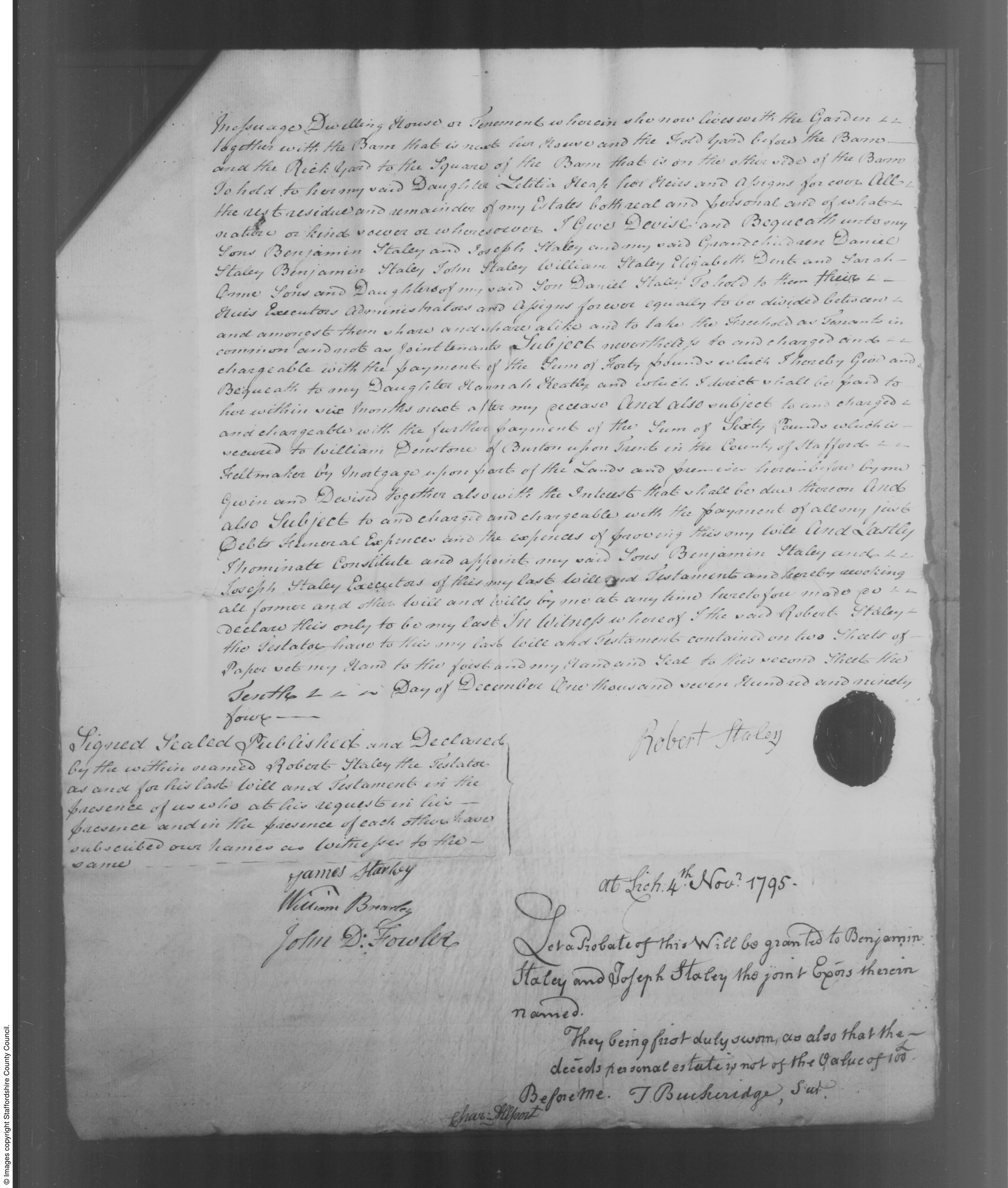

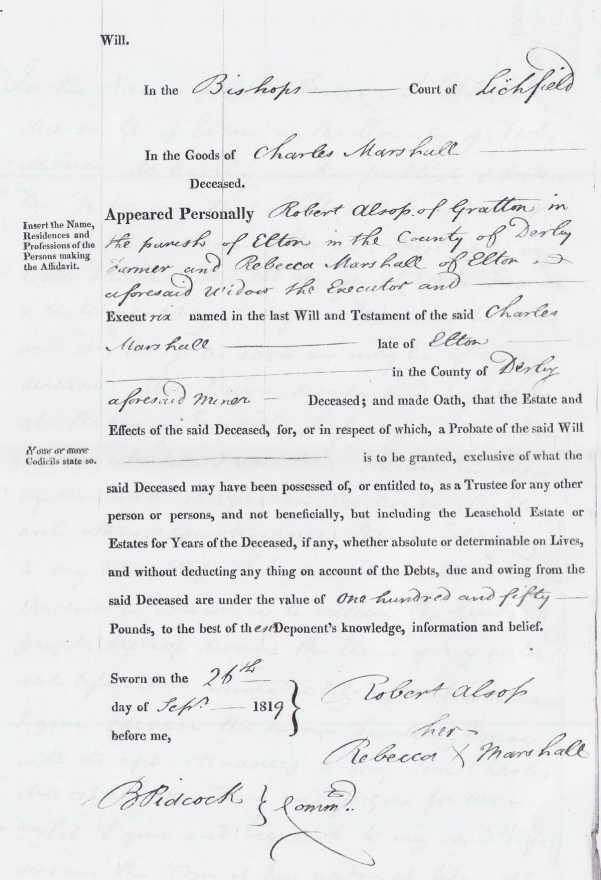

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

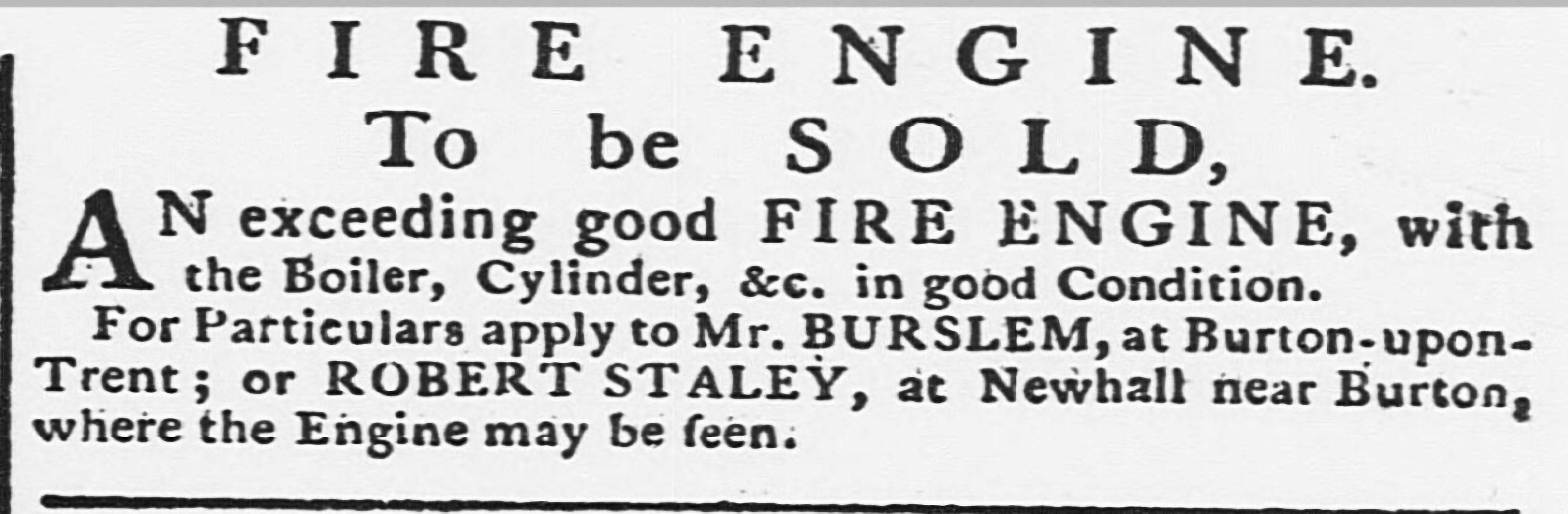

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

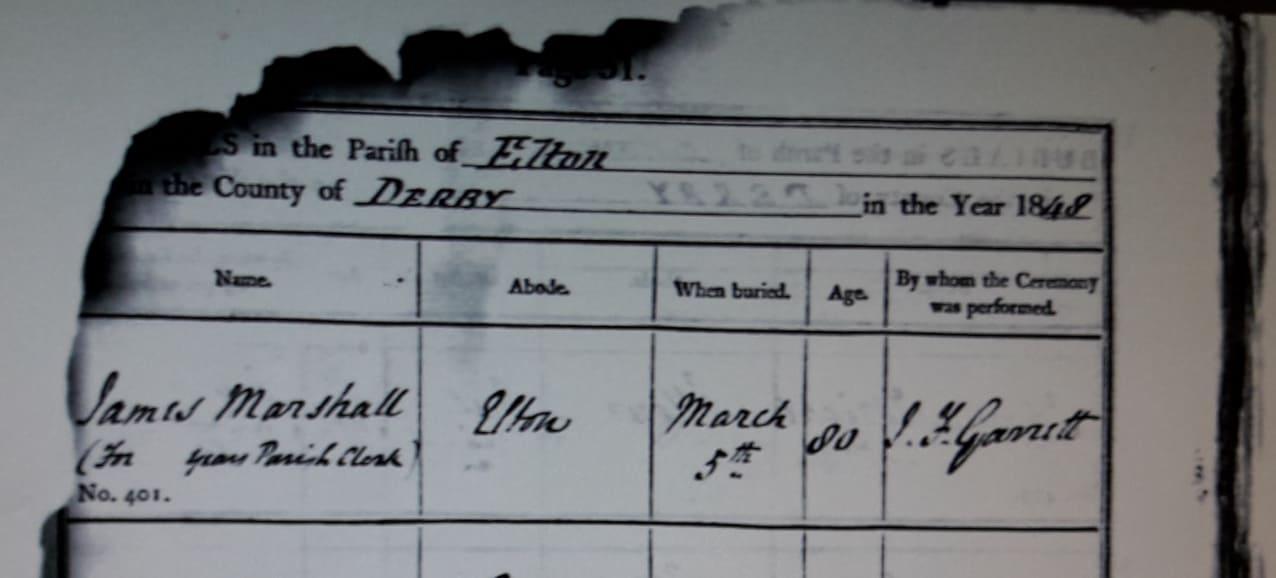

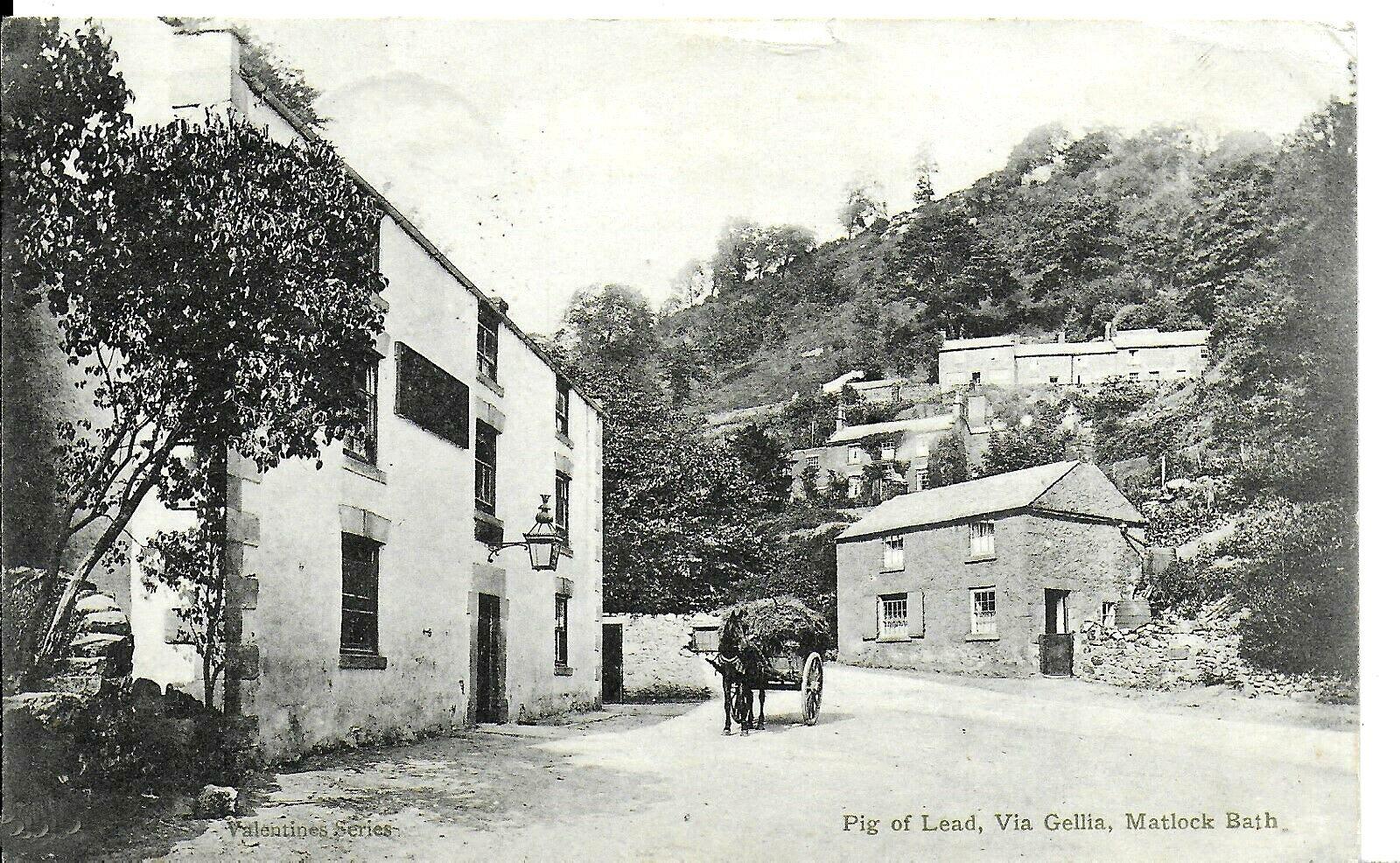

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

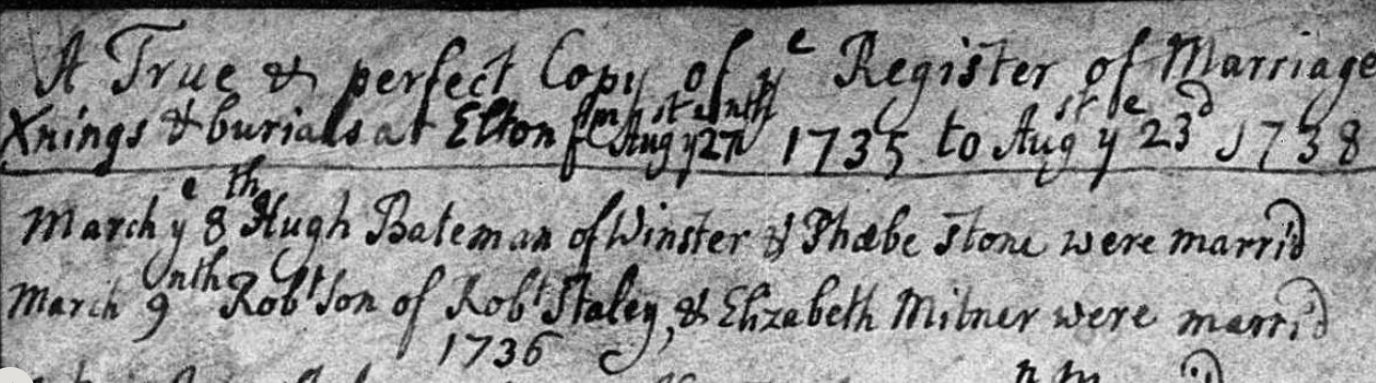

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.

I give, devise and bequeath to Humphrey Trafford Nadin of Church Gresely in the said County of Derby Esquire and John Wilkinson of Newhall aforesaid yeoman all my messuages, lands, tenements, hereditaments and real and personal estates to hold to them, their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns until Richard Moon the youngest of my reputed sons by Elizabeth Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years upon trust that they, my said trustees, (or the survivor of them, his heirs, executors, administrators or assigns), shall and do manage and carry on my farm at Newhall aforesaid and pay and apply the rents, issues and profits of all and every of my said real and personal estates in for and towards the support, maintenance and education of all my reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon until the said Richard Moon my youngest reputed son shall attain his said age of twenty one years and equally share and share and share alike.

And it is my will and desire that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall recruit and keep up the stock upon my farm as they in their discretion shall see occasion or think proper and that the same shall not be diminished. And in case any of my said reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon shall be married before my said reputed youngest son shall attain his age of twenty one years that then it is my will and desire that non of their husbands or wives shall come to my farm or be maintained there or have their abode there. That it is also my will and desire in case my reputed children or any of them shall not be steady to business but instead shall be wild and diminish the stock that then my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority in their discretion to sell and dispose of all or any part of my said personal estate and to put out the money arising from the sale thereof to interest and to pay and apply the interest thereof and also thereunto of the said real estate in for and towards the maintenance, education and support of all my said reputed children by the said

Elizabeth Moon as they my said trustees in their discretion that think proper until the said Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years.Then I give to my grandson Daniel Staley the sum of ten pounds and to each and every of my sons and daughters namely Daniel Staley, Benjamin Staley, John Staley, William Staley, Elizabeth Dent and Sarah Orme and to my niece Ann Brearly the sum of five pounds apiece.

I give to my youngest reputed son Richard Moon one share in the Ashby Canal Navigation and I direct that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority to pay and apply all or any part of the fortune or legacy hereby intended for my youngest reputed son Richard Moon in placing him out to any trade, business or profession as they in their discretion shall think proper.

And I direct that to my said sons and daughters by my late wife and my said niece shall by wholly paid by my said reputed son Richard Moon out of the fortune herby given him. And it is my will and desire that my said reputed children shall deliver into the hands of my executors all the monies that shall arise from the carrying on of my business that is not wanted to carry on the same unto my acting executor and shall keep a just and true account of all disbursements and receipts of the said business and deliver up the same to my acting executor in order that there may not be any embezzlement or defraud amongst them and from and immediately after my said reputed youngest son Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years then I give, devise and bequeath all my real estate and all the residue and remainder of my personal estate of what nature and kind whatsoever and wheresoever unto and amongst all and every my said reputed sons and daughters namely William Moon, Thomas Moon, Joseph Moon, Richard Moon, Ann Moon, Margaret Moon and to my reputed daughter Mary Brearly to hold to them and their respective heirs, executors, administrator and assigns for ever according to the nature and tenure of the same estates respectively to take the same as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.And lastly I nominate and appoint the said Humphrey Trafford Nadin and John Wilkinson executors of this my last will and testament and guardians of all my reputed children who are under age during their respective minorities hereby revoking all former and other wills by me heretofore made and declaring this only to be my last will.

In witness whereof I the said Daniel Staley the testator have to this my last will and testament set my hand and seal the eleventh day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and five.

June 6, 2022 at 12:58 pm #6303In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hollands of Barton under Needwood

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795.

I joined a Barton under Needwood History group and found an incredible amount of information on the Holland family, but first I wanted to make absolutely sure that our Catherine Holland was one of them as there were also Hollands in Newhall. Not only that, on the marriage licence it says that Catherine Holland was from Bretby Park Gate, Stapenhill.

Then I noticed that one of the witnesses on Samuel’s brother Williams marriage to Ann Holland in 1796 was John Hair. Hannah Hair was the wife of Thomas Holland, and they were the Barton under Needwood parents of Catherine. Catherine was born in 1775, and Ann was born in 1767.

The 1851 census clinched it: Catherine Warren 74 years old, widow and formerly a farmers wife, was living in the household of her son John Warren, and her place of birth is listed as Barton under Needwood. In 1841 Catherine was a 64 year old widow, her husband Samuel having died in 1837, and she was living with her son Samuel, a farmer. The 1841 census did not list place of birth, however. Catherine died on 31 March 1861 and does not appear on the 1861 census.

Once I had established that our Catherine Holland was from Barton under Needwood, I had another look at the information available on the Barton under Needwood History group, compiled by local historian Steve Gardner.

Catherine’s parents were Thomas Holland 1737-1828 and Hannah Hair 1739-1822.

Steve Gardner had posted a long list of the dates, marriages and children of the Holland family. The earliest entries in parish registers were Thomae Holland 1562-1626 and his wife Eunica Edwardes 1565-1632. They married on 10th July 1582. They were born, married and died in Barton under Needwood. They were direct ancestors of Catherine Holland, and as such my direct ancestors too.

The known history of the Holland family in Barton under Needwood goes back to Richard De Holland. (Thanks once again to Steve Gardner of the Barton under Needwood History group for this information.)

“Richard de Holland was the first member of the Holland family to become resident in Barton under Needwood (in about 1312) having been granted lands by the Earl of Lancaster (for whom Richard served as Stud and Stock Keeper of the Peak District) The Holland family stemmed from Upholland in Lancashire and had many family connections working for the Earl of Lancaster, who was one of the biggest Barons in England. Lancaster had his own army and lived at Tutbury Castle, from where he ruled over most of the Midlands area. The Earl of Lancaster was one of the main players in the ‘Barons Rebellion’ and the ensuing Battle of Burton Bridge in 1322. Richard de Holland was very much involved in the proceedings which had so angered Englands King. Holland narrowly escaped with his life, unlike the Earl who was executed.

From the arrival of that first Holland family member, the Hollands were a mainstay family in the community, and were in Barton under Needwood for over 600 years.”Continuing with various items of information regarding the Hollands, thanks to Steve Gardner’s Barton under Needwood history pages:

“PART 6 (Final Part)

Some mentions of The Manor of Barton in the Ancient Staffordshire Rolls:

1330. A Grant was made to Herbert de Ferrars, at le Newland in the Manor of Barton.

1378. The Inquisitio bonorum – Johannis Holand — an interesting Inventory of his goods and their value and his debts.

1380. View of Frankpledge ; the Jury found that Richard Holland was feloniously murdered by his wife Joan and Thomas Graunger, who fled. The goods of the deceased were valued at iiij/. iijj. xid. ; one-third went to the dead man, one-third to his son, one- third to the Lord for the wife’s share. Compare 1 H. V. Indictments. (1413.)

That Thomas Graunger of Barton smyth and Joan the wife of Richard de Holond of Barton on the Feast of St. John the Baptist 10 H. II. (1387) had traitorously killed and murdered at night, at Barton, Richard, the husband of the said Joan. (m. 22.)

The names of various members of the Holland family appear constantly among the listed Jurors on the manorial records printed below : —

1539. Richard Holland and Richard Holland the younger are on the Muster Roll of Barton

1583. Thomas Holland and Unica his wife are living at Barton.

1663-4. Visitations. — Barton under Needword. Disclaimers. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.

1609. Richard Holland, Clerk and Alice, his wife.

1663-4. Disclaimers at the Visitation. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.”I was able to find considerably more information on the Hollands in the book “Some Records of the Holland Family (The Hollands of Barton under Needwood, Staffordshire, and the Hollands in History)” by William Richard Holland. Luckily the full text of this book can be found online.

William Richard Holland (Died 1915) An early local Historian and author of the book:

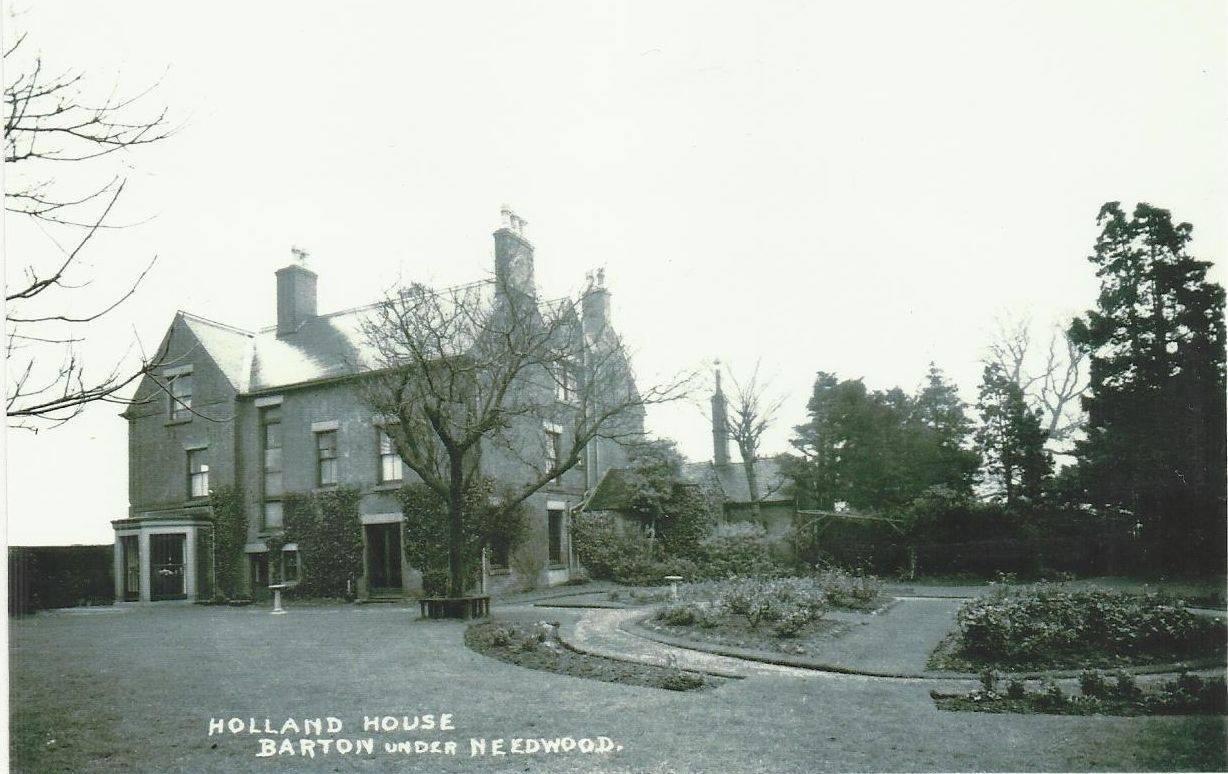

‘Holland House’ taken from the Gardens (sadly demolished in the early 60’s):

Excerpt from the book:

“The charter, dated 1314, granting Richard rights and privileges in Needwood Forest, reads as follows:

“Thomas Earl of Lancaster and Leicester, high-steward of England, to whom all these present shall come, greeting: Know ye, that we have given, &c., to Richard Holland of Barton, and his heirs, housboot, heyboot, and fireboot, and common of pasture, in our forest of Needwood, for all his beasts, as well in places fenced as lying open, with 40 hogs, quit of pawnage in our said forest at all times in the year (except hogs only in fence month). All which premises we will warrant, &c. to the said Richard and his heirs against all people for ever”

“The terms “housboot” “heyboot” and “fireboot” meant that Richard and his heirs were to have the privilege of taking from the Forest, wood needed for house repair and building, hedging material for the repairing of fences, and what was needful for purposes of fuel.”

Further excerpts from the book:

“It may here be mentioned that during the renovation of Barton Church, when the stone pillars were being stripped of the plaster which covered them, “William Holland 1617” was found roughly carved on a pillar near to the belfry gallery, obviously the work of a not too devout member of the family, who, seated in the gallery of that time, occupied himself thus during the service. The inscription can still be seen.”

“The earliest mention of a Holland of Upholland occurs in the reign of John in a Final Concord, made at the Lancashire Assizes, dated November 5th, 1202, in which Uchtred de Chryche, who seems to have had some right in the manor of Upholland, releases his right in fourteen oxgangs* of land to Matthew de Holland, in consideration of the sum of six marks of silver. Thus was planted the Holland Tree, all the early information of which is found in The Victoria County History of Lancaster.

As time went on, the family acquired more land, and with this, increased position. Thus, in the reign of Edward I, a Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, son of Robert, became possessed of the manor of Orrell adjoining Upholland and of the lordship of Hale in the parish of Childwall, and, through marriage with Elizabeth de Samlesbury (co-heiress of Sir Wm. de Samlesbury of Samlesbury, Hall, near to Preston), of the moiety of that manor….

* An oxgang signified the amount of land that could be ploughed by one ox in one day”

“This Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, received Knighthood in the reign of Edward I, as did also his brother William, ancestor of that branch of the family which later migrated to Cheshire. Belonging to this branch are such noteworthy personages as Mrs. Gaskell, the talented authoress, her mother being a Holland of this branch, Sir Henry Holland, Physician to Queen Victoria, and his two sons, the first Viscount Knutsford, and Canon Francis Holland ; Sir Henry’s grandson (the present Lord Knutsford), Canon Scott Holland, etc. Captain Frederick Holland, R.N., late of Ashbourne Hall, Derbyshire, may also be mentioned here.*”

Thanks to the Barton under Needwood history group for the following:

WALES END FARM:

In 1509 it was owned and occupied by Mr Johannes Holland De Wallass end who was a well to do Yeoman Farmer (the origin of the areas name – Wales End). Part of the building dates to 1490 making it probably the oldest building still standing in the Village:

I found records for all of the Holland’s listed on the Barton under Needwood History group and added them to my ancestry tree. The earliest will I found was for Eunica Edwardes, then Eunica Holland, who died in 1632.

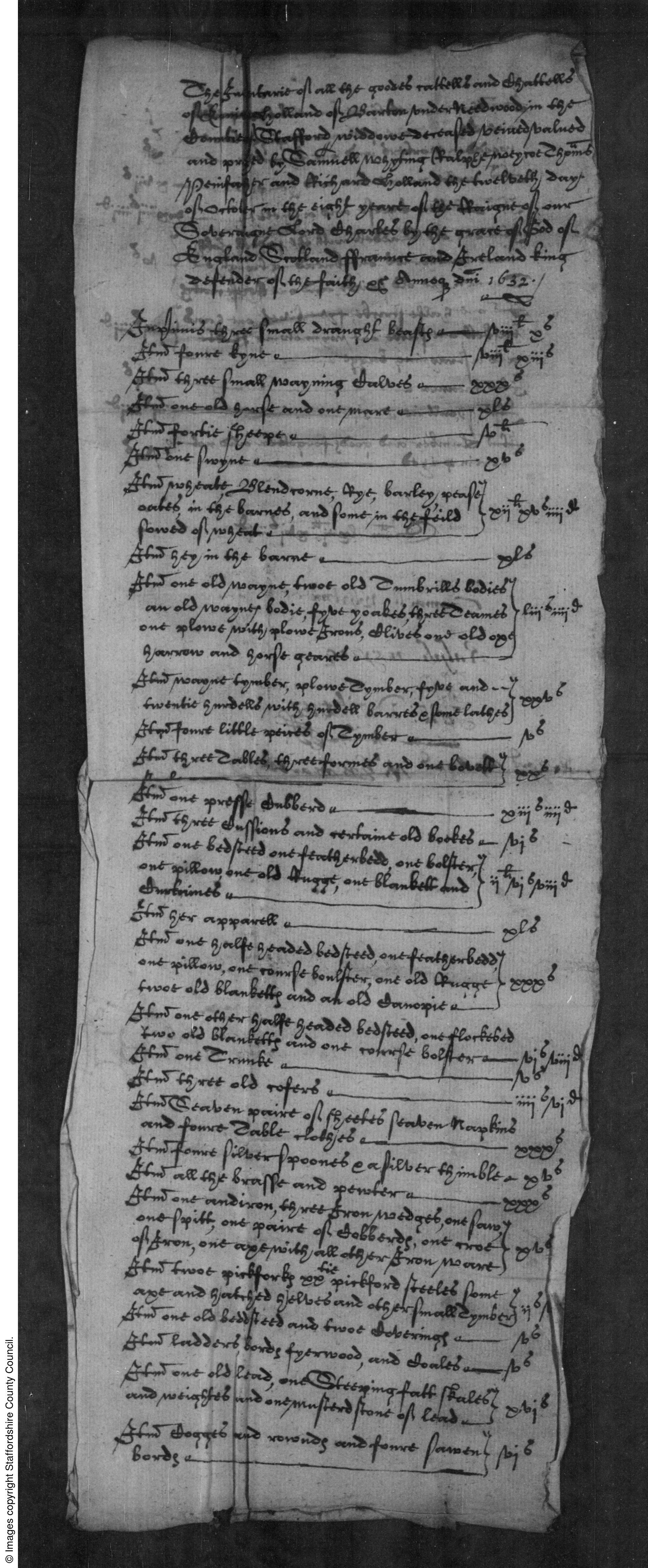

A page from the 1632 will and inventory of Eunica (Unice) Holland:

I’d been reading about “pedigree collapse” just before I found out her maiden name of Edwardes. Edwards is my own maiden name.

“In genealogy, pedigree collapse describes how reproduction between two individuals who knowingly or unknowingly share an ancestor causes the family tree of their offspring to be smaller than it would otherwise be.

Without pedigree collapse, a person’s ancestor tree is a binary tree, formed by the person, the parents, grandparents, and so on. However, the number of individuals in such a tree grows exponentially and will eventually become impossibly high. For example, a single individual alive today would, over 30 generations going back to the High Middle Ages, have roughly a billion ancestors, more than the total world population at the time. This apparent paradox occurs because the individuals in the binary tree are not distinct: instead, a single individual may occupy multiple places in the binary tree. This typically happens when the parents of an ancestor are cousins (sometimes unbeknownst to themselves). For example, the offspring of two first cousins has at most only six great-grandparents instead of the normal eight. This reduction in the number of ancestors is pedigree collapse. It collapses the binary tree into a directed acyclic graph with two different, directed paths starting from the ancestor who in the binary tree would occupy two places.” via wikipediaThere is nothing to suggest, however, that Eunica’s family were related to my fathers family, and the only evidence so far in my tree of pedigree collapse are the marriages of Orgill cousins, where two sets of grandparents are repeated.

A list of Holland ancestors:

Catherine Holland 1775-1861

her parents:

Thomas Holland 1737-1828 Hannah Hair 1739-1832

Thomas’s parents:

William Holland 1696-1756 Susannah Whiteing 1715-1752

William’s parents:

William Holland 1665- Elizabeth Higgs 1675-1720

William’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1634-1681 Katherine Owen 1634-1728

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1606-1680 Margaret Belcher 1608-1664

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1562-1626 Eunice Edwardes 1565- 1632May 13, 2022 at 10:50 am #6293In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Lincolnshire Families

Thanks to the 1851 census, we know that William Eaton was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire. He was baptised on 29 November 1768 at St Wulfram’s church; his father was William Eaton and his mother Elizabeth.

St Wulfram’s in Grantham painted by JMW Turner in 1797:

I found a marriage for a William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose in the city of Lincoln in 1761, but it seemed unlikely as they were both of that parish, and with no discernable links to either Grantham or Nottingham.

But there were two marriages registered for William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose: one in Lincoln in 1761 and one in Hawkesworth Nottinghamshire in 1767, the year before William junior was baptised in Grantham. Hawkesworth is between Grantham and Nottingham, and this seemed much more likely.

Elizabeth’s name is spelled Rose on her marriage records, but spelled Rouse on her baptism. It’s not unusual for spelling variations to occur, as the majority of people were illiterate and whoever was recording the event wrote what it sounded like.

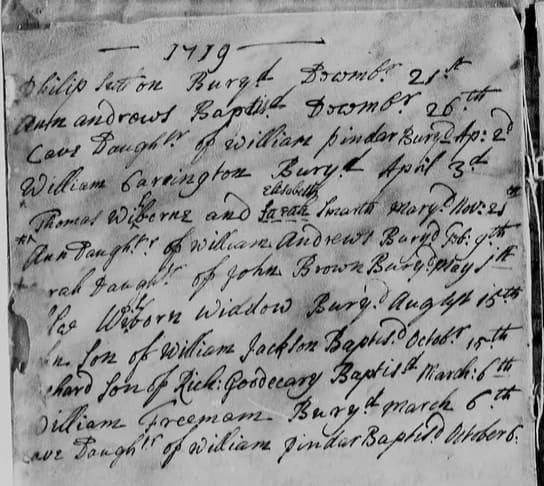

Elizabeth Rouse was baptised on 26th December 1746 in Gunby St Nicholas (there is another Gunby in Lincolnshire), a short distance from Grantham. Her father was Richard Rouse; her mother Cave Pindar. Cave is a curious name and I wondered if it had been mistranscribed, but it appears to be correct and clearly says Cave on several records.

Richard Rouse married Cave Pindar 21 July 1744 in South Witham, not far from Grantham.

Richard was born in 1716 in North Witham. His father was William Rouse; his mothers name was Jane.

Cave Pindar was born in 1719 in Gunby St Nicholas, near Grantham. Her father was William Pindar, but sadly her mothers name is not recorded in the parish baptism register. However a marriage was registered between William Pindar and Elizabeth Holmes in Gunby St Nicholas in October 1712.

William Pindar buried a daughter Cave on 2 April 1719 and baptised a daughter Cave on 6 Oct 1719:

Elizabeth Holmes was baptised in Gunby St Nicholas on 6th December 1691. Her father was John Holmes; her mother Margaret Hod.

Margaret Hod would have been born circa 1650 to 1670 and I haven’t yet found a baptism record for her. According to several other public trees on an ancestry website, she was born in 1654 in Essenheim, Germany. This was surprising! According to these trees, her father was Johannes Hod (Blodt|Hoth) (1609–1677) and her mother was Maria Appolonia Witters (1620–1656).

I did not think it very likely that a young woman born in Germany would appear in Gunby St Nicholas in the late 1600’s, and did a search for Hod’s in and around Grantham. Indeed there were Hod’s living in the area as far back as the 1500’s, (a Robert Hod was baptised in Grantham in 1552), and no doubt before, but the parish records only go so far back. I think it’s much more likely that her parents were local, and that the page with her baptism recorded on the registers is missing.

Of the many reasons why parish registers or some of the pages would be destroyed or lost, this is another possibility. Lincolnshire is on the east coast of England:

“All of England suffered from a “monster” storm in November of 1703 that killed a reported 8,000 people. Seaside villages suffered greatly and their church and civil records may have been lost.”

A Margeret Hod, widow, died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1691, the same year that Elizabeth Holmes was born. Elizabeth’s mother was Margaret Hod. Perhaps the widow who died was Margaret Hod’s mother? I did wonder if Margaret Hod had died shortly after her daughter’s birth, and that her husband had died sometime between the conception and birth of his child. The Black Death or Plague swept through Lincolnshire in 1680 through 1690; such an eventually would be possible. But Margaret’s name would have been registered as Holmes, not Hod.

Cave Pindar’s father William was born in Swinstead, Lincolnshire, also near to Grantham, on the 28th December, 1690, and he died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1756. William’s father is recorded as Thomas Pinder; his mother Elizabeth.

GUNBY: The village name derives from a “farmstead or village of a man called Gunni”, from the Old Scandinavian person name, and ‘by’, a farmstead, village or settlement.

Gunby Grade II listed Anglican church is dedicated to St Nicholas. Of 15th-century origin, it was rebuilt by Richard Coad in 1869, although the Perpendicular tower remained. April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-

my grandmother Florence Warren 1906-1988

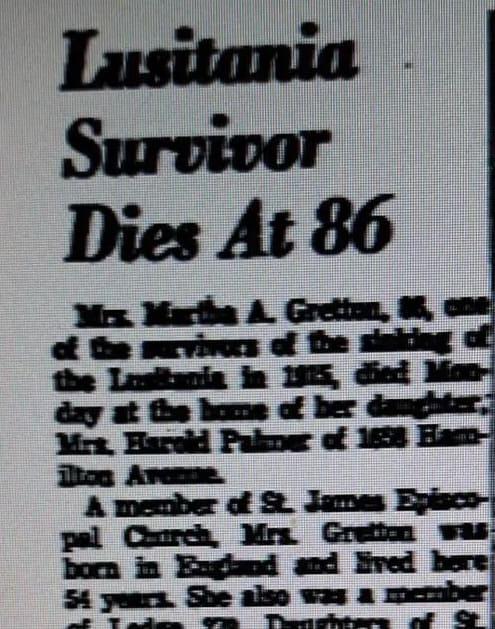

her mother and my great grandmother Florence Gretton 1881-1927

her mother Sarah Orgill 1840-1910

her mother Elizabeth Orgill 1803-1876

her mother Sarah Boss 1783-1847

her mother Elizabeth Page 1749-

her mother Mary Potter 1719-1780

and her mother and my 7x great grandmother Mary 1680-You could say it leads us to the very heart of England, as these Leicestershire villages are as far from the coast as it’s possible to be. There are countless other maternal lines to follow, of course, but only one of mothers of mothers, and ours takes us to Leicestershire.

The blacksmiths

Sarah Boss was the daughter of Michael Boss 1755-1807, a blacksmith in Measham, and Elizabeth Page of nearby Hartshorn, just over the county border in Derbyshire.

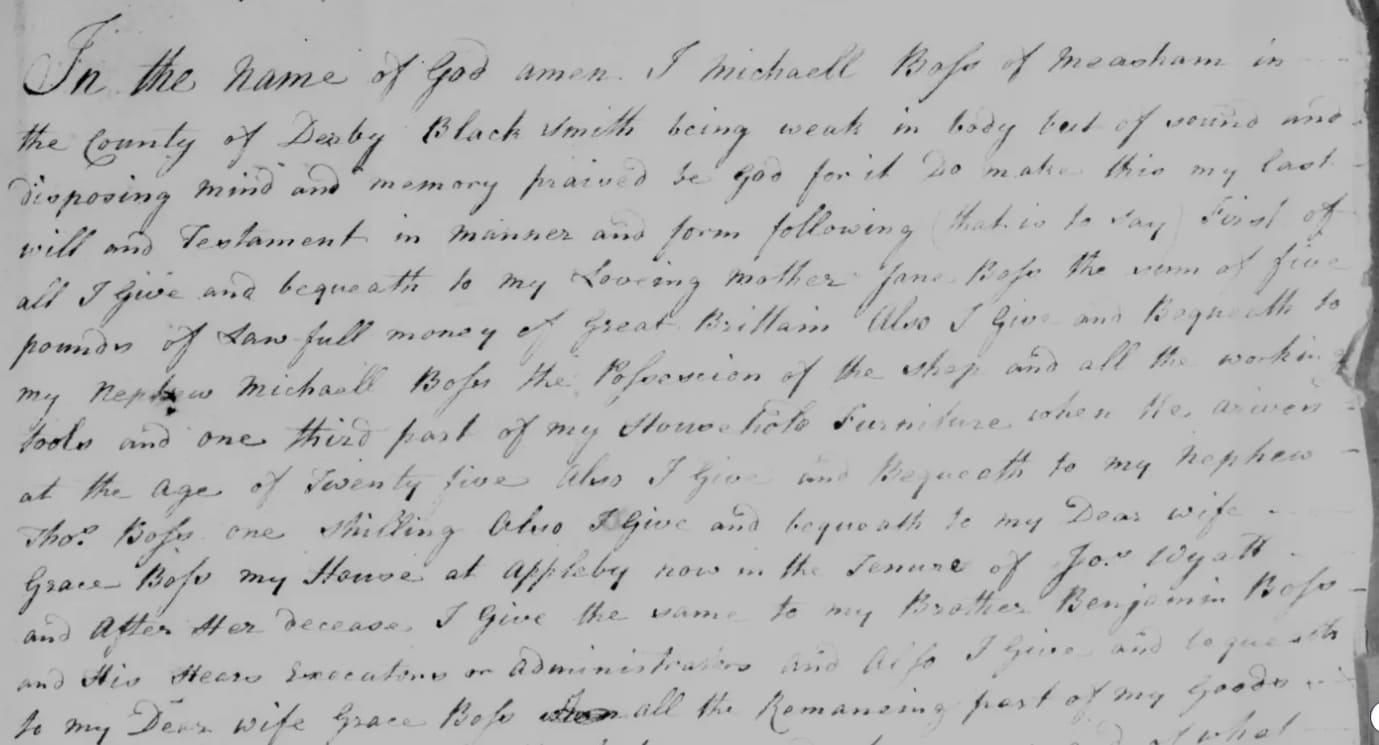

An earlier Michael Boss, a blacksmith of Measham, died in 1772, and in his will he left the possession of the blacksmiths shop and all the working tools and a third of the household furniture to Michael, who he named as his nephew. He left his house in Appleby Magna to his wife Grace, and five pounds to his mother Jane Boss. As none of Michael and Grace’s children are mentioned in the will, perhaps it can be assumed that they were childless.

The will of Michael Boss, 1772, Measham:

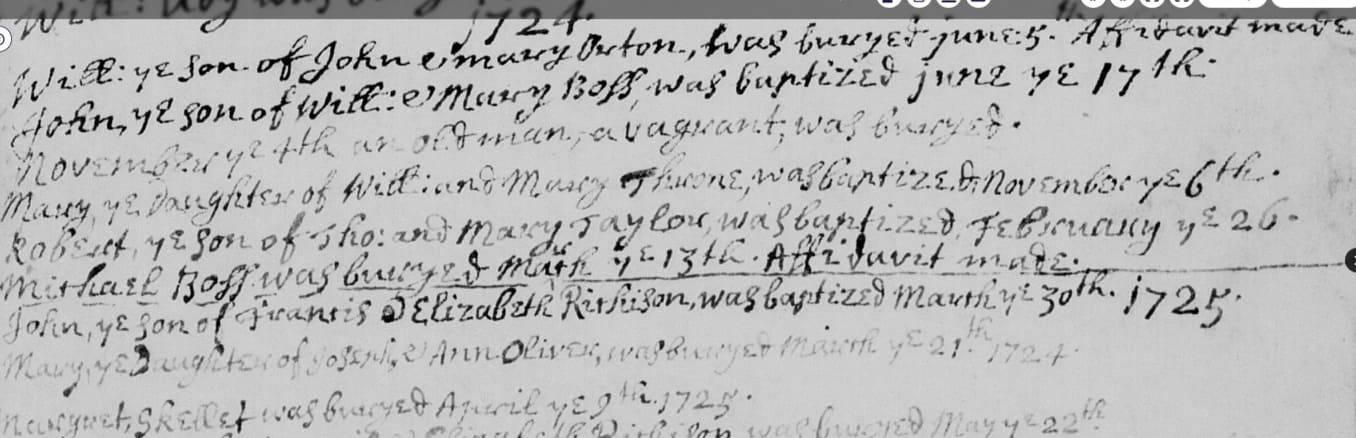

Michael Boss the uncle was born in Appleby Magna in 1724. His parents were Michael Boss of Nelson in the Thistles and Jane Peircivall of Appleby Magna, who were married in nearby Mancetter in 1720.

Information worth noting on the Appleby Magna website:

In 1752 the calendar in England was changed from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, as a result 11 days were famously “lost”. But for the recording of Church Registers another very significant change also took place, the start of the year was moved from March 25th to our more familiar January 1st.

Before 1752 the 1st day of each new year was March 25th, Lady Day (a significant date in the Christian calendar). The year number which we all now use for calculating ages didn’t change until March 25th. So, for example, the day after March 24th 1750 was March 25th 1751, and January 1743 followed December 1743.

This March to March recording can be seen very clearly in the Appleby Registers before 1752. Between 1752 and 1768 there appears slightly confused recording, so dates should be carefully checked. After 1768 the recording is more fully by the modern calendar year.Michael Boss the uncle married Grace Cuthbert. I haven’t yet found the birth or parents of Grace, but a blacksmith by the name of Edward Cuthbert is mentioned on an Appleby Magna history website:

An Eighteenth Century Blacksmith’s Shop in Little Appleby

by Alan RobertsCuthberts inventory

The inventory of Edward Cuthbert provides interesting information about the household possessions and living arrangements of an eighteenth century blacksmith. Edward Cuthbert (als. Cutboard) settled in Appleby after the Restoration to join the handful of blacksmiths already established in the parish, including the Wathews who were prominent horse traders. The blacksmiths may have all worked together in the same shop at one time. Edward and his wife Sarah recorded the baptisms of several of their children in the parish register. Somewhat sadly three of the boys named after their father all died either in infancy or as young children. Edward’s inventory which was drawn up in 1732, by which time he was probably a widower and his children had left home, suggests that they once occupied a comfortable two-storey house in Little Appleby with an attached workshop, well equipped with all the tools for repairing farm carts, ploughs and other implements, for shoeing horses and for general ironmongery.

Edward Cuthbert born circa 1660, married Joane Tuvenet in 1684 in Swepston cum Snarestone , and died in Appleby in 1732. Tuvenet is a French name and suggests a Huguenot connection, but this isn’t our family, and indeed this Edward Cuthbert is not likely to be Grace’s father anyway.

Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page appear to have married twice: once in 1776, and once in 1779. Both of the documents exist and appear correct. Both marriages were by licence. They both mention Michael is a blacksmith.

Their first daughter, Elizabeth, was baptized in February 1777, just nine months after the first wedding. It’s not known when she was born, however, and it’s possible that the marriage was a hasty one. But why marry again three years later?

But Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page did not marry twice.

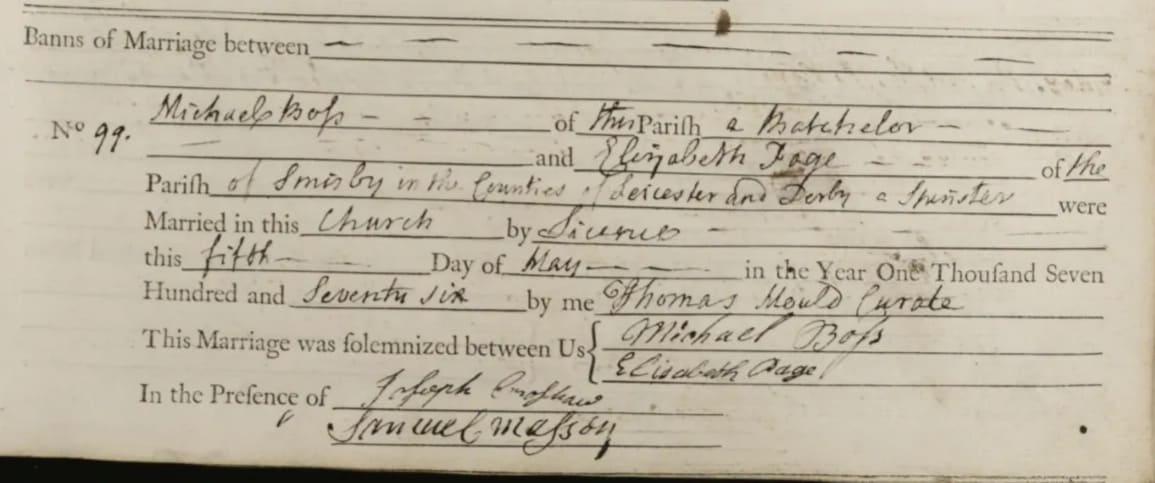

Elizabeth Page from Smisby was born in 1752 and married Michael Boss on the 5th of May 1776 in Measham. On the marriage licence allegations and bonds, Michael is a bachelor.

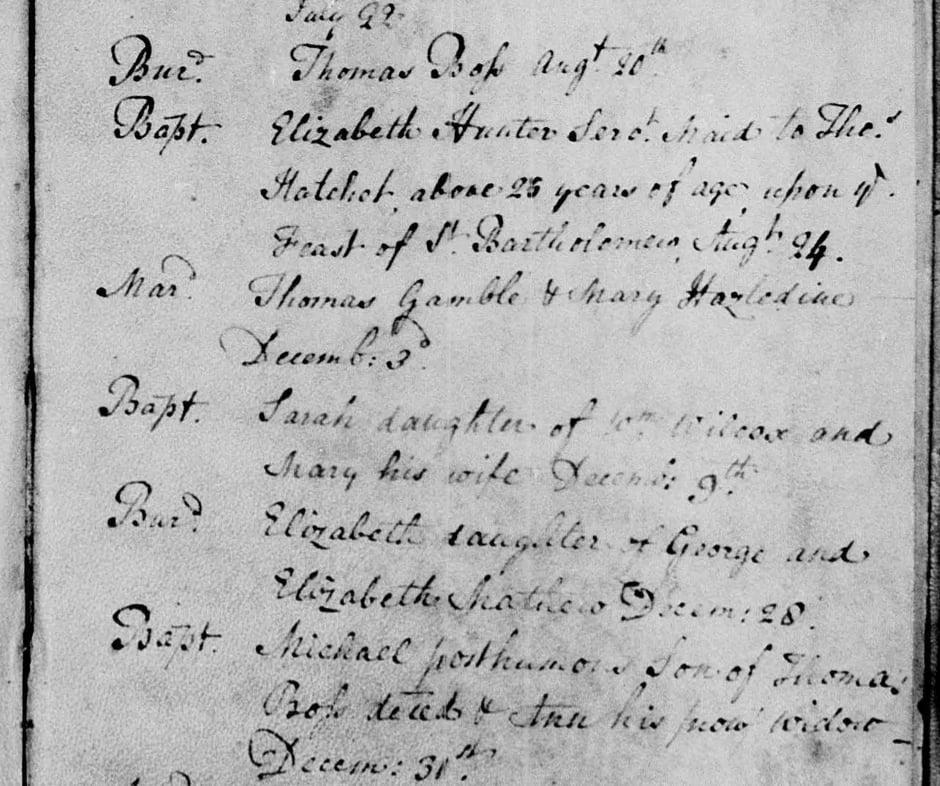

Baby Elizabeth was baptised in Measham on the 9th February 1777. Mother Elizabeth died on the 18th February 1777, also in Measham.

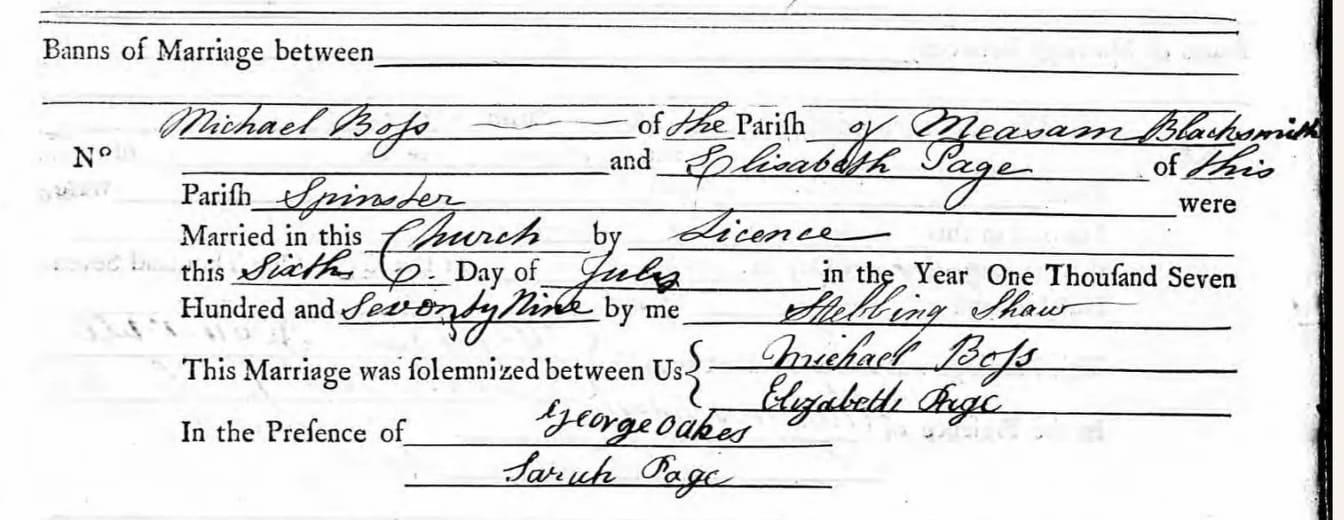

In 1779 Michael Boss married another Elizabeth Page! She was born in 1749 in Hartshorn, and Michael is a widower on the marriage licence allegations and bonds.

Hartshorn and Smisby are neighbouring villages, hence the confusion. But a closer look at the documents available revealed the clues. Both Elizabeth Pages were literate, and indeed their signatures on the marriage registers are different:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Smisby in 1776:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Harsthorn in 1779:

Not only did Michael Boss marry two women both called Elizabeth Page but he had an unusual start in life as well. His uncle Michael Boss left him the blacksmith business and a third of his furniture. This was all in the will. But which of Uncle Michaels brothers was nephew Michaels father?