-

AuthorSearch Results

-

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

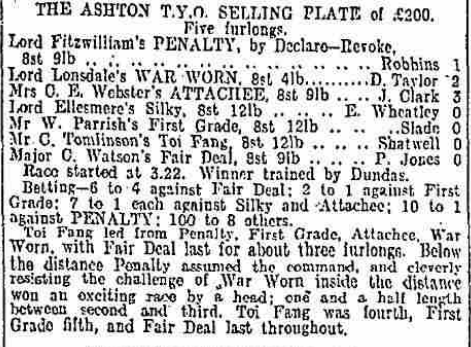

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

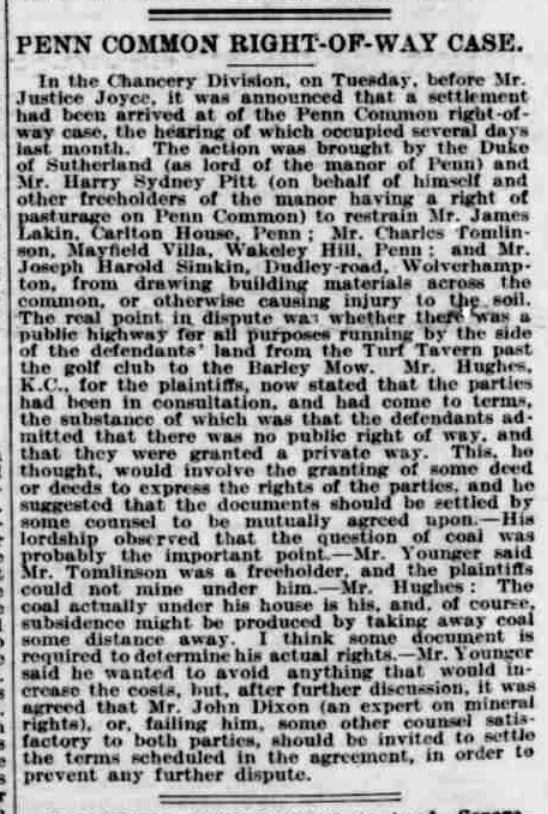

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

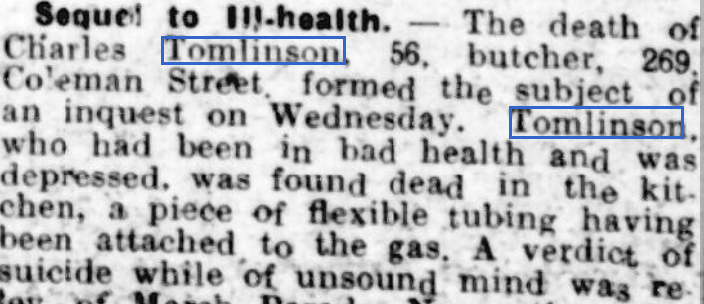

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

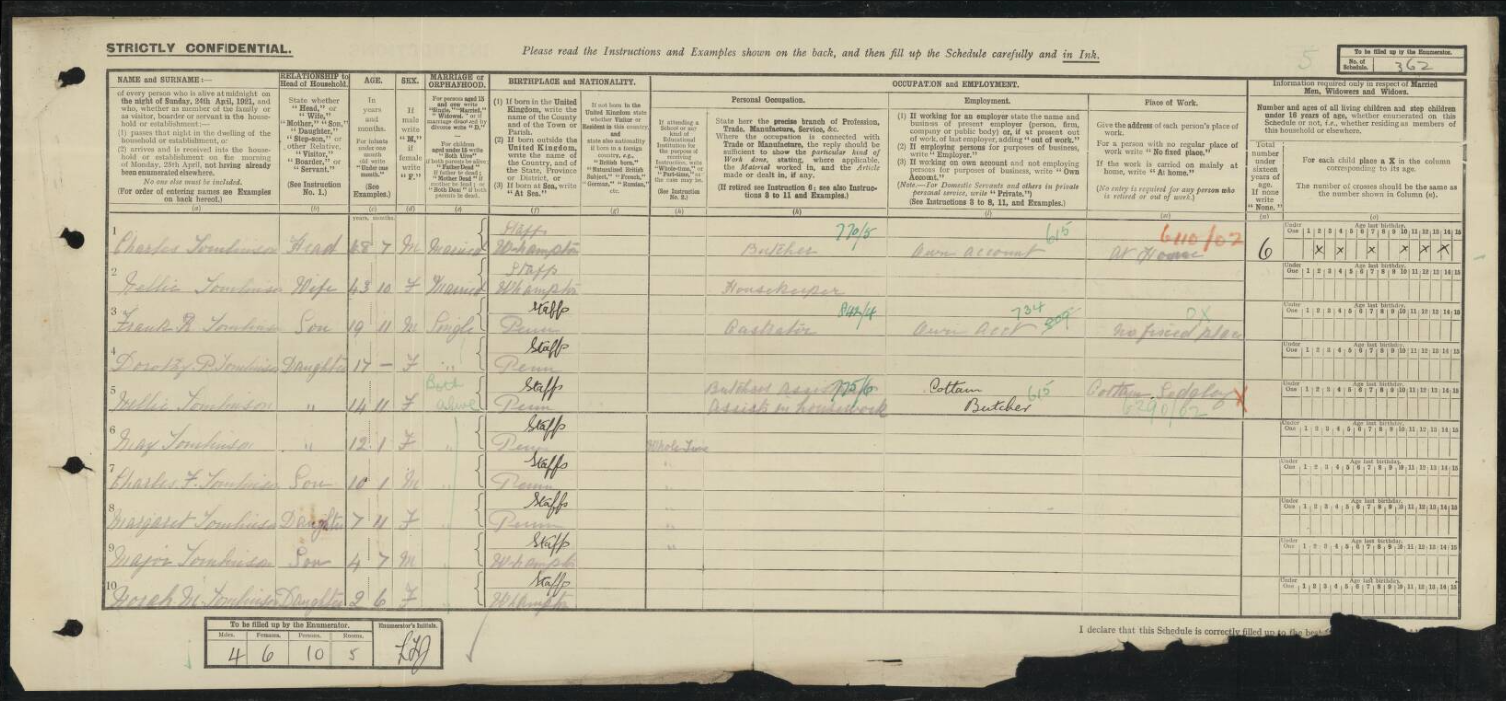

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

February 2, 2022 at 1:15 pm #6268In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 9

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Lyamungu 3rd January 1945

Dearest Family.

We had a novel Christmas this year. We decided to avoid the expense of

entertaining and being entertained at Lyamungu, and went off to spend Christmas

camping in a forest on the Western slopes of Kilimanjaro. George decided to combine

business with pleasure and in this way we were able to use Government transport.

We set out the day before Christmas day and drove along the road which skirts

the slopes of Kilimanjaro and first visited a beautiful farm where Philip Teare, the ex

Game Warden, and his wife Mary are staying. We had afternoon tea with them and then

drove on in to the natural forest above the estate and pitched our tent beside a small

clear mountain stream. We decorated the tent with paper streamers and a few small

balloons and John found a small tree of the traditional shape which we decorated where

it stood with tinsel and small ornaments.We put our beer, cool drinks for the children and bottles of fresh milk from Simba

Estate, in the stream and on Christmas morning they were as cold as if they had been in

the refrigerator all night. There were not many presents for the children, there never are,

but they do not seem to mind and are well satisfied with a couple of balloons apiece,

sweets, tin whistles and a book each.George entertain the children before breakfast. He can make a magical thing out

of the most ordinary balloon. The children watched entranced as he drew on his pipe

and then blew the smoke into the balloon. He then pinched the neck of the balloon

between thumb and forefinger and released the smoke in little puffs. Occasionally the

balloon ejected a perfect smoke ring and the forest rang with shouts of “Do it again

Daddy.” Another trick was to blow up the balloon to maximum size and then twist the

neck tightly before releasing. Before subsiding the balloon darted about in a crazy

fashion causing great hilarity. Such fun, at the cost of a few pence.After breakfast George went off to fish for trout. John and Jim decided that they

also wished to fish so we made rods out of sticks and string and bent pins and they

fished happily, but of course quite unsuccessfully, for hours. Both of course fell into the

stream and got soaked, but I was prepared for this, and the little stream was so shallow

that they could not come to any harm. Henry played happily in the sand and I had a

most peaceful morning.Hamisi roasted a chicken in a pot over the camp fire and the jelly set beautifully in the

stream. So we had grilled trout and chicken for our Christmas dinner. I had of course

taken an iced cake for the occasion and, all in all, it was a very successful Christmas day.

On Boxing day we drove down to the plains where George was to investigate a

report of game poaching near the Ngassari Furrow. This is a very long ditch which has

been dug by the Government for watering the Masai stock in the area. It is also used by

game and we saw herds of zebra and wildebeest, and some Grant’s Gazelle and

giraffe, all comparatively tame. At one point a small herd of zebra raced beside the lorry

apparently enjoying the fun of a gallop. They were all sleek and fat and looked wild and

beautiful in action.We camped a considerable distance from the water but this precaution did not

save us from the mosquitoes which launched a vicious attack on us after sunset, so that

we took to our beds unusually early. They were on the job again when we got up at

sunrise so I was very glad when we were once more on our way home.“I like Christmas safari. Much nicer that silly old party,” said John. I agree but I think

it is time that our children learned to play happily with others. There are no other young

children at Lyamungu though there are two older boys and a girl who go to boarding

school in Nairobi.On New Years Day two Army Officers from the military camp at Moshi, came for

tea and to talk game hunting with George. I think they rather enjoy visiting a home and

seeing children and pets around.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 14 May 1945

Dearest Family.

So the war in Europe is over at last. It is such marvellous news that I can hardly

believe it. To think that as soon as George can get leave we will go to England and

bring Ann and George home with us to Tanganyika. When we know when this leave can

be arranged we will want Kate to join us here as of course she must go with us to

England to meet George’s family. She has become so much a part of your lives that I

know it will be a wrench for you to give her up but I know that you will all be happy to

think that soon our family will be reunited.The V.E. celebrations passed off quietly here. We all went to Moshi to see the

Victory Parade of the King’s African Rifles and in the evening we went to a celebration

dinner at the Game Warden’s house. Besides ourselves the Moores had invited the

Commanding Officer from Moshi and a junior officer. We had a very good dinner and

many toasts including one to Mrs Moore’s brother, Oliver Milton who is fighting in Burma

and has recently been awarded the Military Cross.There was also a celebration party for the children in the grounds of the Moshi

Club. Such a spread! I think John and Jim sampled everything. We mothers were

having our tea separately and a friend laughingly told me to turn around and have a look.

I did, and saw the long tea tables now deserted by all the children but my two sons who

were still eating steadily, and finding the party more exciting than the game of Musical

Bumps into which all the other children had entered with enthusiasm.There was also an extremely good puppet show put on by the Italian prisoners

of war from the camp at Moshi. They had made all the puppets which included well

loved characters like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the Babes in the Wood as

well as more sophisticated ones like an irritable pianist and a would be prima donna. The

most popular puppets with the children were a native askari and his family – a very

happy little scene. I have never before seen a puppet show and was as entranced as

the children. It is amazing what clever manipulation and lighting can do. I believe that the

Italians mean to take their puppets to Nairobi and am glad to think that there, they will

have larger audiences to appreciate their art.George has just come in, and I paused in my writing to ask him for the hundredth

time when he thinks we will get leave. He says I must be patient because it may be a

year before our turn comes. Shipping will be disorganised for months to come and we

cannot expect priority simply because we have been separated so long from our

children. The same situation applies to scores of other Government Officials.

I have decided to write the story of my childhood in South Africa and about our

life together in Tanganyika up to the time Ann and George left the country. I know you

will have told Kate these stories, but Ann and George were so very little when they left

home that I fear that they cannot remember much.My Mother-in-law will have told them about their father but she can tell them little

about me. I shall send them one chapter of my story each month in the hope that they

may be interested and not feel that I am a stranger when at last we meet again.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 19th September 1945

Dearest Family.

In a months time we will be saying good-bye to Lyamungu. George is to be

transferred to Mbeya and I am delighted, not only as I look upon Mbeya as home, but

because there is now a primary school there which John can attend. I feel he will make

much better progress in his lessons when he realises that all children of his age attend

school. At present he is putting up a strong resistance to learning to read and spell, but

he writes very neatly, does his sums accurately and shows a real talent for drawing. If

only he had the will to learn I feel he would do very well.Jim now just four, is too young for lessons but too intelligent to be interested in

the ayah’s attempts at entertainment. Yes I’ve had to engage a native girl to look after

Henry from 9 am to 12.30 when I supervise John’s Correspondence Course. She is

clean and amiable, but like most African women she has no initiative at all when it comes

to entertaining children. Most African men and youths are good at this.I don’t regret our stay at Lyamungu. It is a beautiful spot and the change to the

cooler climate after the heat of Morogoro has been good for all the children. John is still

tall for his age but not so thin as he was and much less pale. He is a handsome little lad

with his large brown eyes in striking contrast to his fair hair. He is wary of strangers but

very observant and quite uncanny in the way he sums up people. He seldom gets up

to mischief but I have a feeling he eggs Jim on. Not that Jim needs egging.Jim has an absolute flair for mischief but it is all done in such an artless manner that

it is not easy to punish him. He is a very sturdy child with a cap of almost black silky hair,

eyes brown, like mine, and a large mouth which is quick to smile and show most beautiful

white and even teeth. He is most popular with all the native servants and the Game

Scouts. The servants call Jim, ‘Bwana Tembo’ (Mr Elephant) because of his sturdy

build.Henry, now nearly two years old, is quite different from the other two in

appearance. He is fair complexioned and fair haired like Ann and Kate, with large, black

lashed, light grey eyes. He is a good child, not so merry as Jim was at his age, nor as

shy as John was. He seldom cries, does not care to be cuddled and is independent and

strong willed. The servants call Henry, ‘Bwana Ndizi’ (Mr Banana) because he has an

inexhaustible appetite for this fruit. Fortunately they are very inexpensive here. We buy

an entire bunch which hangs from a beam on the back verandah, and pluck off the

bananas as they ripen. This way there is no waste and the fruit never gets bruised as it

does in greengrocers shops in South Africa. Our three boys make a delightful and

interesting trio and I do wish you could see them for yourselves.We are delighted with the really beautiful photograph of Kate. She is an

extraordinarily pretty child and looks so happy and healthy and a great credit to you.

Now that we will be living in Mbeya with a school on the doorstep I hope that we will

soon be able to arrange for her return home.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 30th October 1945

Dearest Family.

How nice to be able to write c/o Game Dept. Mbeya at the head of my letters.

We arrived here safely after a rather tiresome journey and are installed in a tiny house on

the edge of the township.We left Lyamungu early on the morning of the 22nd. Most of our goods had

been packed on the big Ford lorry the previous evening, but there were the usual

delays and farewells. Of our servants, only the cook, Hamisi, accompanied us to

Mbeya. Japhet, Tovelo and the ayah had to be paid off and largesse handed out.

Tovelo’s granny had come, bringing a gift of bananas, and she also brought her little

granddaughter to present a bunch of flowers. The child’s little scolded behind is now

completely healed. Gifts had to be found for them too.At last we were all aboard and what a squash it was! Our few pieces of furniture

and packing cases and trunks, the cook, his wife, the driver and the turney boy, who

were to take the truck back to Lyamungu, and all their bits and pieces, bunches of

bananas and Fanny the dog were all crammed into the body of the lorry. George, the

children and I were jammed together in the cab. Before we left George looked

dubiously at the tyres which were very worn and said gloomily that he thought it most

unlikely that we would make our destination, Dodoma.Too true! Shortly after midday, near Kwakachinja, we blew a back tyre and there

was a tedious delay in the heat whilst the wheel was changed. We were now without a

spare tyre and George said that he would not risk taking the Ford further than Babati,

which is less than half way to Dodoma. He drove very slowly and cautiously to Babati

where he arranged with Sher Mohammed, an Indian trader, for a lorry to take us to

Dodoma the next morning.It had been our intention to spend the night at the furnished Government

Resthouse at Babati but when we got there we found that it was already occupied by

several District Officers who had assembled for a conference. So, feeling rather

disgruntled, we all piled back into the lorry and drove on to a place called Bereku where

we spent an uncomfortable night in a tumbledown hut.Before dawn next morning Sher Mohammed’s lorry drove up, and there was a

scramble to dress by the light of a storm lamp. The lorry was a very dilapidated one and

there was already a native woman passenger in the cab. I felt so tired after an almost

sleepless night that I decided to sit between the driver and this woman with the sleeping

Henry on my knee. It was as well I did, because I soon found myself dosing off and

drooping over towards the woman. Had she not been there I might easily have fallen

out as the battered cab had no door. However I was alert enough when daylight came

and changed places with the woman to our mutual relief. She was now able to converse

with the African driver and I was able to enjoy the scenery and the fresh air!

George, John and Jim were less comfortable. They sat in the lorry behind the

cab hemmed in by packing cases. As the lorry was an open one the sun beat down

unmercifully upon them until George, ever resourceful, moved a table to the front of the

truck. The two boys crouched under this and so got shelter from the sun but they still had

to endure the dust. Fanny complicated things by getting car sick and with one thing and

another we were all jolly glad to get to Dodoma.We spent the night at the Dodoma Hotel and after hot baths, a good meal and a

good nights rest we cheerfully boarded a bus of the Tanganyika Bus Service next

morning to continue our journey to Mbeya. The rest of the journey was uneventful. We slept two nights on the road, the first at Iringa Hotel and the second at Chimala. We

reached Mbeya on the 27th.I was rather taken aback when I first saw the little house which has been allocated

to us. I had become accustomed to the spacious houses we had in Morogoro and

Lyamungu. However though the house is tiny it is secluded and has a long garden

sloping down to the road in front and another long strip sloping up behind. The front

garden is shaded by several large cypress and eucalyptus trees but the garden behind

the house has no shade and consists mainly of humpy beds planted with hundreds of

carnations sadly in need of debudding. I believe that the previous Game Ranger’s wife

cultivated the carnations and, by selling them, raised money for War Funds.

Like our own first home, this little house is built of sun dried brick. Its original

owners were Germans. It is now rented to the Government by the Custodian of Enemy

Property, and George has his office in another ex German house.This afternoon we drove to the school to arrange about enrolling John there. The

school is about four miles out of town. It was built by the German settlers in the late

1930’s and they were justifiably proud of it. It consists of a great assembly hall and

classrooms in one block and there are several attractive single storied dormitories. This

school was taken over by the Government when the Germans were interned on the

outbreak of war and many improvements have been made to the original buildings. The

school certainly looks very attractive now with its grassed playing fields and its lawns and

bright flower beds.The Union Jack flies from a tall flagpole in front of the Hall and all traces of the

schools German origin have been firmly erased. We met the Headmaster, Mr

Wallington, and his wife and some members of the staff. The school is co-educational

and caters for children from the age of seven to standard six. The leaving age is elastic

owing to the fact that many Tanganyika children started school very late because of lack

of educational facilities in this country.The married members of the staff have their own cottages in the grounds. The

Matrons have quarters attached to the dormitories for which they are responsible. I felt

most enthusiastic about the school until I discovered that the Headmaster is adamant

upon one subject. He utterly refuses to take any day pupils at the school. So now our

poor reserved Johnny will have to adjust himself to boarding school life.

We have arranged that he will start school on November 5th and I shall be very

busy trying to assemble his school uniform at short notice. The clothing list is sensible.

Boys wear khaki shirts and shorts on weekdays with knitted scarlet jerseys when the

weather is cold. On Sundays they wear grey flannel shorts and blazers with the silver

and scarlet school tie.Mbeya looks dusty, brown and dry after the lush evergreen vegetation of

Lyamungu, but I prefer this drier climate and there are still mountains to please the eye.

In fact the lower slopes of Lolesa Mountain rise at the upper end of our garden.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 21st November 1945

Dearest Family.

We’re quite settled in now and I have got the little house fixed up to my

satisfaction. I have engaged a rather uncouth looking houseboy but he is strong and

capable and now that I am not tied down in the mornings by John’s lessons I am able to

go out occasionally in the mornings and take Jim and Henry to play with other children.

They do not show any great enthusiasm but are not shy by nature as John is.

I have had a good deal of heartache over putting John to boarding school. It

would have been different had he been used to the company of children outside his

own family, or if he had even known one child there. However he seems to be adjusting

himself to the life, though slowly. At least he looks well and tidy and I am quite sure that

he is well looked after.I must confess that when the time came for John to go to school I simply did not

have the courage to take him and he went alone with George, looking so smart in his

new uniform – but his little face so bleak. The next day, Sunday, was visiting day but the

Headmaster suggested that we should give John time to settle down and not visit him

until Wednesday.When we drove up to the school I spied John on the far side of the field walking

all alone. Instead of running up with glad greetings, as I had expected, he came almost

reluctently and had little to say. I asked him to show me his dormitory and classroom and

he did so politely as though I were a stranger. At last he volunteered some information.

“Mummy,” he said in an awed voice, Do you know on the night I came here they burnt a

man! They had a big fire and they burnt him.” After a blank moment the penny dropped.

Of course John had started school and November the fifth but it had never entered my

head to tell him about that infamous character, Guy Fawkes!I asked John’s Matron how he had settled down. “Well”, she said thoughtfully,

“John is very good and has not cried as many of the juniors do when they first come

here, but he seems to keep to himself all the time.” I went home very discouraged but

on the Sunday John came running up with another lad of about his own age.” This is my

friend Marks,” he announced proudly. I could have hugged Marks.Mbeya is very different from the small settlement we knew in the early 1930’s.

Gone are all the colourful characters from the Lupa diggings for the alluvial claims are all

worked out now, gone also are our old friends the Menzies from the Pub and also most

of the Government Officials we used to know. Mbeya has lost its character of a frontier

township and has become almost suburban.The social life revolves around two places, the Club and the school. The Club

which started out as a little two roomed building, has been expanded and the golf

course improved. There are also tennis courts and a good library considering the size of

the community. There are frequent parties and dances, though most of the club revenue

comes from Bar profits. The parties are relatively sober affairs compared with the parties

of the 1930’s.The school provides entertainment of another kind. Both Mr and Mrs Wallington

are good amateur actors and I am told that they run an Amateur Dramatic Society. Every

Wednesday afternoon there is a hockey match at the school. Mbeya town versus a

mixed team of staff and scholars. The match attracts almost the whole European

population of Mbeya. Some go to play hockey, others to watch, and others to snatch

the opportunity to visit their children. I shall have to try to arrange a lift to school when

George is away on safari.I have now met most of the local women and gladly renewed an old friendship

with Sheilagh Waring whom I knew two years ago at Morogoro. Sheilagh and I have

much in common, the same disregard for the trappings of civilisation, the same sense of

the ludicrous, and children. She has eight to our six and she has also been cut off by the

war from two of her children. Sheilagh looks too young and pretty to be the mother of so

large a family and is, in fact, several years younger than I am. her husband, Donald, is a

large quiet man who, as far as I can judge takes life seriously.Our next door neighbours are the Bank Manager and his wife, a very pleasant

couple though we seldom meet. I have however had correspondence with the Bank

Manager. Early on Saturday afternoon their houseboy brought a note. It informed me

that my son was disturbing his rest by precipitating a heart attack. Was I aware that my

son was about 30 feet up in a tree and balanced on a twig? I ran out and,sure enough,

there was Jim, right at the top of the tallest eucalyptus tree. It would be the one with the

mound of stones at the bottom! You should have heard me fluting in my most

wheedling voice. “Sweets, Jimmy, come down slowly dear, I’ve some nice sweets for

you.”I’ll bet that little story makes you smile. I remember how often you have told me

how, as a child, I used to make your hearts turn over because I had no fear of heights

and how I used to say, “But that is silly, I won’t fall.” I know now only too well, how you

must have felt.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 14th January 1946

Dearest Family.

I hope that by now you have my telegram to say that Kate got home safely

yesterday. It was wonderful to have her back and what a beautiful child she is! Kate

seems to have enjoyed the train journey with Miss Craig, in spite of the tears she tells

me she shed when she said good-bye to you. She also seems to have felt quite at

home with the Hopleys at Salisbury. She flew from Salisbury in a small Dove aircraft

and they had a smooth passage though Kate was a little airsick.I was so excited about her home coming! This house is so tiny that I had to turn

out the little store room to make a bedroom for her. With a fresh coat of whitewash and

pretty sprigged curtains and matching bedspread, borrowed from Sheilagh Waring, the

tiny room looks most attractive. I had also iced a cake, made ice-cream and jelly and

bought crackers for the table so that Kate’s home coming tea could be a proper little

celebration.I was pleased with my preparations and then, a few hours before the plane was

due, my crowned front tooth dropped out, peg and all! When my houseboy wants to

describe something very tatty, he calls it “Second-hand Kabisa.” Kabisa meaning

absolutely. That is an apt description of how I looked and felt. I decided to try some

emergency dentistry. I think you know our nearest dentist is at Dar es Salaam five

hundred miles away.First I carefully dried the tooth and with a match stick covered the peg and base

with Durofix. I then took the infants rubber bulb enema, sucked up some heat from a

candle flame and pumped it into the cavity before filling that with Durofix. Then hopefully

I stuck the tooth in its former position and held it in place for several minutes. No good. I

sent the houseboy to a shop for Scotine and tried the whole process again. No good

either.When George came home for lunch I appealed to him for advice. He jokingly

suggested that a maize seed jammed into the space would probably work, but when

he saw that I really was upset he produced some chewing gum and suggested that I

should try that . I did and that worked long enough for my first smile anyway.

George and the three boys went to meet Kate but I remained at home to

welcome her there. I was afraid that after all this time away Kate might be reluctant to

rejoin the family but she threw her arms around me and said “Oh Mummy,” We both

shed a few tears and then we both felt fine.How gay Kate is, and what an infectious laugh she has! The boys follow her

around in admiration. John in fact asked me, “Is Kate a Princess?” When I said

“Goodness no, Johnny, she’s your sister,” he explained himself by saying, “Well, she

has such golden hair.” Kate was less complementary. When I tucked her in bed last night

she said, “Mummy, I didn’t expect my little brothers to be so yellow!” All three boys

have been taking a course of Atebrin, an anti-malarial drug which tinges skin and eyeballs

yellow.So now our tiny house is bursting at its seams and how good it feels to have one

more child under our roof. We are booked to sail for England in May and when we return

we will have Ann and George home too. Then I shall feel really content.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 2nd March 1946

Dearest Family.

My life just now is uneventful but very busy. I am sewing hard and knitting fast to

try to get together some warm clothes for our leave in England. This is not a simple

matter because woollen materials are in short supply and very expensive, and now that

we have boarding school fees to pay for both Kate and John we have to budget very

carefully indeed.Kate seems happy at school. She makes friends easily and seems to enjoy

communal life. John also seems reconciled to school now that Kate is there. He no

longer feels that he is the only exile in the family. He seems to rub along with the other

boys of his age and has a couple of close friends. Although Mbeya School is coeducational

the smaller boys and girls keep strictly apart. It is considered extremely

cissy to play with girls.The local children are allowed to go home on Sundays after church and may bring

friends home with them for the day. Both John and Kate do this and Sunday is a very

busy day for me. The children come home in their Sunday best but bring play clothes to

change into. There is always a scramble to get them to bath and change again in time to

deliver them to the school by 6 o’clock.When George is home we go out to the school for the morning service. This is

taken by the Headmaster Mr Wallington, and is very enjoyable. There is an excellent

school choir to lead the singing. The service is the Church of England one, but is

attended by children of all denominations, except the Roman Catholics. I don’t think that

more than half the children are British. A large proportion are Greeks, some as old as

sixteen, and about the same number are Afrikaners. There are Poles and non-Nazi

Germans, Swiss and a few American children.All instruction is through the medium of English and it is amazing how soon all the

foreign children learn to chatter in English. George has been told that we will return to

Mbeya after our leave and for that I am very thankful as it means that we will still be living

near at hand when Jim and Henry start school. Because many of these children have to

travel many hundreds of miles to come to school, – Mbeya is a two day journey from the

railhead, – the school year is divided into two instead of the usual three terms. This

means that many of these children do not see their parents for months at a time. I think

this is a very sad state of affairs especially for the seven and eight year olds but the

Matrons assure me , that many children who live on isolated farms and stations are quite

reluctant to go home because they miss the companionship and the games and

entertainment that the school offers.My only complaint about the life here is that I see far too little of George. He is

kept extremely busy on this range and is hardly at home except for a few days at the

months end when he has to be at his office to check up on the pay vouchers and the

issue of ammunition to the Scouts. George’s Range takes in the whole of the Southern

Province and the Southern half of the Western Province and extends to the border with

Northern Rhodesia and right across to Lake Tanganyika. This vast area is patrolled by

only 40 Game Scouts because the Department is at present badly under staffed, due

partly to the still acute shortage of rifles, but even more so to the extraordinary reluctance

which the Government shows to allocate adequate funds for the efficient running of the

Department.The Game Scouts must see that the Game Laws are enforced, protect native

crops from raiding elephant, hippo and other game animals. Report disease amongst game and deal with stock raiding lions. By constantly going on safari and checking on

their work, George makes sure the range is run to his satisfaction. Most of the Game

Scouts are fine fellows but, considering they receive only meagre pay for dangerous

and exacting work, it is not surprising that occasionally a Scout is tempted into accepting

a bribe not to report a serious infringement of the Game Laws and there is, of course,

always the temptation to sell ivory illicitly to unscrupulous Indian and Arab traders.

Apart from supervising the running of the Range, George has two major jobs.

One is to supervise the running of the Game Free Area along the Rhodesia –

Tanganyika border, and the other to hunt down the man-eating lions which for years have

terrorised the Njombe District killing hundreds of Africans. Yes I know ‘hundreds’ sounds

fantastic, but this is perfectly true and one day, when the job is done and the official

report published I shall send it to you to prove it!I hate to think of the Game Free Area and so does George. All the game from

buffalo to tiny duiker has been shot out in a wide belt extending nearly two hundred

miles along the Northern Rhodesia -Tanganyika border. There are three Europeans in

widely spaced camps who supervise this slaughter by African Game Guards. This

horrible measure is considered necessary by the Veterinary Departments of

Tanganyika, Rhodesia and South Africa, to prevent the cattle disease of Rinderpest

from spreading South.When George is home however, we do relax and have fun. On the Saturday

before the school term started we took Kate and the boys up to the top fishing camp in

the Mporoto Mountains for her first attempt at trout fishing. There are three of these

camps built by the Mbeya Trout Association on the rivers which were first stocked with

the trout hatched on our farm at Mchewe. Of the three, the top camp is our favourite. The

scenery there is most glorious and reminds me strongly of the rivers of the Western

Cape which I so loved in my childhood.The river, the Kawira, flows from the Rungwe Mountain through a narrow valley

with hills rising steeply on either side. The water runs swiftly over smooth stones and

sometimes only a foot or two below the level of the banks. It is sparkling and shallow,

but in places the water is deep and dark and the banks high. I had a busy day keeping

an eye on the boys, especially Jim, who twice climbed out on branches which overhung

deep water. “Mummy, I was only looking for trout!”How those kids enjoyed the freedom of the camp after the comparative

restrictions of town. So did Fanny, she raced about on the hills like a mad dog chasing

imaginary rabbits and having the time of her life. To escape the noise and commotion

George had gone far upstream to fish and returned in the late afternoon with three good

sized trout and four smaller ones. Kate proudly showed George the two she had caught

with the assistance or our cook Hamisi. I fear they were caught in a rather unorthodox

manner but this I kept a secret from George who is a stickler for the orthodox in trout

fishing.Eleanor.

Jacksdale England 24th June 1946

Dearest Family.

Here we are all together at last in England. You cannot imagine how wonderful it

feels to have the whole Rushby family reunited. I find myself counting heads. Ann,

George, Kate, John, Jim, and Henry. All present and well. We had a very pleasant trip

on the old British India Ship Mantola. She was crowded with East Africans going home

for the first time since the war, many like us, eagerly looking forward to a reunion with their

children whom they had not seen for years. There was a great air of anticipation and

good humour but a little anxiety too.“I do hope our children will be glad to see us,” said one, and went on to tell me

about a Doctor from Dar es Salaam who, after years of separation from his son had

recently gone to visit him at his school. The Doctor had alighted at the railway station

where he had arranged to meet his son. A tall youth approached him and said, very

politely, “Excuse me sir. Are you my Father?” Others told me of children who had

become so attached to their relatives in England that they gave their parents a very cool

reception. I began to feel apprehensive about Ann and George but fortunately had no

time to mope.Oh, that washing and ironing for six! I shall remember for ever that steamy little

laundry in the heat of the Red Sea and queuing up for the ironing and the feeling of guilt

at the size of my bundle. We met many old friends amongst the passengers, and made

some new ones, so the voyage was a pleasant one, We did however have our

anxious moments.John was the first to disappear and we had an anxious search for him. He was

quite surprised that we had been concerned. “I was just talking to my friend Chinky

Chinaman in his workshop.” Could John have called him that? Then, when I returned to

the cabin from dinner one night I found Henry swigging Owbridge’s Lung Tonic. He had

drunk half the bottle neat and the label said ‘five drops in water’. Luckily it did not harm

him.Jim of course was forever risking his neck. George had forbidden him to climb on

the railings but he was forever doing things which no one had thought of forbidding him

to do, like hanging from the overhead pipes on the deck or standing on the sill of a

window and looking down at the well deck far below. An Officer found him doing this and

gave me the scolding.Another day he climbed up on a derrick used for hoisting cargo. George,

oblivious to this was sitting on the hatch cover with other passengers reading a book. I

was in the wash house aft on the same deck when Kate rushed in and said, “Mummy

come and see Jim.” Before I had time to more than gape, the butcher noticed Jim and

rushed out knife in hand. “Get down from there”, he bellowed. Jim got, and with such

speed that he caught the leg or his shorts on a projecting piece of metal. The cotton

ripped across the seam from leg to leg and Jim stood there for a humiliating moment in a

sort of revealing little kilt enduring the smiles of the passengers who had looked up from

their books at the butcher’s shout.That incident cured Jim of his urge to climb on the ship but he managed to give

us one more fright. He was lost off Dover. People from whom we enquired said, “Yes

we saw your little boy. He was by the railings watching that big aircraft carrier.” Now Jim,

though mischievous , is very obedient. It was not until George and I had conducted an

exhaustive search above and below decks that I really became anxious. Could he have

fallen overboard? Jim was returned to us by an unamused Officer. He had been found

in one of the lifeboats on the deck forbidden to children.Our ship passed Dover after dark and it was an unforgettable sight. Dover Castle

and the cliffs were floodlit for the Victory Celebrations. One of the men passengers sat

down at the piano and played ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, and people sang and a few

wept. The Mantola docked at Tilbury early next morning in a steady drizzle.

There was a dockers strike on and it took literally hours for all the luggage to be

put ashore. The ships stewards simply locked the public rooms and went off leaving the

passengers shivering on the docks. Eventually damp and bedraggled, we arrived at St

Pancras Station and were given a warm welcome by George’s sister Cath and her

husband Reg Pears, who had come all the way from Nottingham to meet us.

As we had to spend an hour in London before our train left for Nottingham,

George suggested that Cath and I should take the children somewhere for a meal. So

off we set in the cold drizzle, the boys and I without coats and laden with sundry

packages, including a hand woven native basket full of shoes. We must have looked like

a bunch of refugees as we stood in the hall of The Kings Cross Station Hotel because a

supercilious waiter in tails looked us up and down and said, “I’m afraid not Madam”, in

answer to my enquiry whether the hotel could provide lunch for six.

Anyway who cares! We had lunch instead at an ABC tea room — horrible

sausage and a mound or rather sloppy mashed potatoes, but very good ice-cream.

After the train journey in a very grimy third class coach, through an incredibly green and

beautiful countryside, we eventually reached Nottingham and took a bus to Jacksdale,

where George’s mother and sisters live in large detached houses side by side.

Ann and George were at the bus stop waiting for us, and thank God, submitted

to my kiss as though we had been parted for weeks instead of eight years. Even now

that we are together again my heart aches to think of all those missed years. They have

not changed much and I would have picked them out of a crowd, but Ann, once thin and

pale, is now very rosy and blooming. She still has her pretty soft plaits and her eyes are

still a clear calm blue. Young George is very striking looking with sparkling brown eyes, a

ready, slightly lopsided smile, and charming manners.Mother, and George’s elder sister, Lottie Giles, welcomed us at the door with the

cheering news that our tea was ready. Ann showed us the way to mother’s lovely lilac

tiled bathroom for a wash before tea. Before I had even turned the tap, Jim had hung

form the glass towel rail and it lay in three pieces on the floor. There have since been

similar tragedies. I can see that life in civilisation is not without snags.I am most grateful that Ann and George have accepted us so naturally and

affectionately. Ann said candidly, “Mummy, it’s a good thing that you had Aunt Cath with

you when you arrived because, honestly, I wouldn’t have known you.”Eleanor.

Jacksdale England 28th August 1946

Dearest Family.

I am sorry that I have not written for some time but honestly, I don’t know whether

I’m coming or going. Mother handed the top floor of her house to us and the

arrangement was that I should tidy our rooms and do our laundry and Mother would

prepare the meals except for breakfast. It looked easy at first. All the rooms have wall to

wall carpeting and there was a large vacuum cleaner in the box room. I was told a

window cleaner would do the windows.Well the first time I used the Hoover I nearly died of fright. I pressed the switch

and immediately there was a roar and the bag filled with air to bursting point, or so I

thought. I screamed for Ann and she came at the run. I pointed to the bag and shouted

above the din, “What must I do? It’s going to burst!” Ann looked at me in astonishment

and said, “But Mummy that’s the way it works.” I couldn’t have her thinking me a

complete fool so I switched the current off and explained to Ann how it was that I had

never seen this type of equipment in action. How, in Tanganyika , I had never had a

house with electricity and that, anyway, electric equipment would be superfluous

because floors are of cement which the houseboy polishes by hand, one only has a

few rugs or grass mats on the floor. “But what about Granny’s house in South Africa?’”

she asked, so I explained about your Josephine who threatened to leave if you

bought a Hoover because that would mean that you did not think she kept the house

clean. The sad fact remains that, at fourteen, Ann knows far more about housework than I

do, or rather did! I’m learning fast.The older children all go to school at different times in the morning. Ann leaves first

by bus to go to her Grammar School at Sutton-in-Ashfield. Shortly afterwards George

catches a bus for Nottingham where he attends the High School. So they have

breakfast in relays, usually scrambled egg made from a revolting dried egg mixture.

Then there are beds to make and washing and ironing to do, so I have little time for

sightseeing, though on a few afternoons George has looked after the younger children

and I have gone on bus tours in Derbyshire. Life is difficult here with all the restrictions on

foodstuffs. We all have ration books so get our fair share but meat, fats and eggs are

scarce and expensive. The weather is very wet. At first I used to hang out the washing

and then rush to bring it in when a shower came. Now I just let it hang.We have left our imprint upon my Mother-in-law’s house for ever. Henry upset a

bottle of Milk of Magnesia in the middle of the pale fawn bedroom carpet. John, trying to

be helpful and doing some dusting, broke one of the delicate Dresden china candlesticks

which adorn our bedroom mantelpiece.Jim and Henry have wrecked the once

professionally landscaped garden and all the boys together bored a large hole through

Mother’s prized cherry tree. So now Mother has given up and gone off to Bournemouth

for a much needed holiday. Once a week I have the capable help of a cleaning woman,

called for some reason, ‘Mrs Two’, but I have now got all the cooking to do for eight. Mrs

Two is a godsend. She wears, of all things, a print mob cap with a hole in it. Says it

belonged to her Grandmother. Her price is far beyond Rubies to me, not so much

because she does, in a couple of hours, what it takes me all day to do, but because she

sells me boxes of fifty cigarettes. Some non-smoking relative, who works in Players

tobacco factory, passes on his ration to her. Until Mrs Two came to my rescue I had

been starved of cigarettes. Each time I asked for them at the shop the grocer would say,

“Are you registered with us?” Only very rarely would some kindly soul sell me a little

packet of five Woodbines.England is very beautiful but the sooner we go home to Tanganyika, the better.

On this, George and I and the children agree.Eleanor.

Jacksdale England 20th September 1946

Dearest Family.

Our return passages have now been booked on the Winchester Castle and we

sail from Southampton on October the sixth. I look forward to returning to Tanganyika but

hope to visit England again in a few years time when our children are older and when

rationing is a thing of the past.I have grown fond of my Sisters-in-law and admire my Mother-in-law very much.

She has a great sense of humour and has entertained me with stories of her very

eventful life, and told me lots of little stories of the children which did not figure in her

letters. One which amused me was about young George. During one of the air raids

early in the war when the sirens were screaming and bombers roaring overhead Mother

made the two children get into the cloak cupboard under the stairs. Young George

seemed quite unconcerned about the planes and the bombs but soon an anxious voice

asked in the dark, “Gran, what will I do if a spider falls on me?” I am afraid that Mother is

going to miss Ann and George very much.I had a holiday last weekend when Lottie and I went up to London on a spree. It

was a most enjoyable weekend, though very rushed. We placed ourselves in the

hands of Thos. Cook and Sons and saw most of the sights of London and were run off

our feet in the process. As you all know London I shall not describe what I saw but just

to say that, best of all, I enjoyed walking along the Thames embankment in the evening

and the changing of the Guard at Whitehall. On Sunday morning Lottie and I went to

Kew Gardens and in the afternoon walked in Kensington Gardens.We went to only one show, ‘The Skin of our Teeth’ starring Vivienne Leigh.

Neither of us enjoyed the performance at all and regretted having spent so much on

circle seats. The show was far too highbrow for my taste, a sort of satire on the survival

of the human race. Miss Leigh was unrecognisable in a blond wig and her voice strident.

However the night was not a dead loss as far as entertainment was concerned as we

were later caught up in a tragicomedy at our hotel.We had booked communicating rooms at the enormous Imperial Hotel in Russell

Square. These rooms were comfortably furnished but very high up, and we had a rather

terrifying and dreary view from the windows of the enclosed courtyard far below. We

had some snacks and a chat in Lottie’s room and then I moved to mine and went to bed.

I had noted earlier that there was a special lock on the outer door of my room so that

when the door was closed from the inside it automatically locked itself.

I was just dropping off to sleep when I heard a hammering which seemed to

come from my wardrobe. I got up, rather fearfully, and opened the wardrobe door and

noted for the first time that the wardrobe was set in an opening in the wall and that the

back of the wardrobe also served as the back of the wardrobe in the room next door. I

quickly shut it again and went to confer with Lottie.Suddenly a male voice was raised next door in supplication, “Mary Mother of

God, Help me! They’ve locked me in!” and the hammering resumed again, sometimes

on the door, and then again on the back of the wardrobe of the room next door. Lottie

had by this time joined me and together we listened to the prayers and to the

hammering. Then the voice began to threaten, “If you don’t let me out I’ll jump out of the

window.” Great consternation on our side of the wall. I went out into the passage and

called through the door, “You’re not locked in. Come to your door and I’ll tell you how to

open it.” Silence for a moment and then again the prayers followed by a threat. All the

other doors in the corridor remained shut.Luckily just then a young man and a woman came walking down the corridor and I

explained the situation. The young man hurried off for the night porter who went into the

next door room. In a matter of minutes there was peace next door. When the night

porter came out into the corridor again I asked for an explanation. He said quite casually,

“It’s all right Madam. He’s an Irish Gentleman in Show Business. He gets like this on a

Saturday night when he has had a drop too much. He won’t give any more trouble

now.” And he didn’t. Next morning at breakfast Lottie and I tried to spot the gentleman in

the Show Business, but saw no one who looked like the owner of that charming Irish

voice.George had to go to London on business last Monday and took the older

children with him for a few hours of sight seeing. They returned quite unimpressed.

Everything was too old and dirty and there were far too many people about, but they

had enjoyed riding on the escalators at the tube stations, and all agreed that the highlight

of the trip was, “Dad took us to lunch at the Chicken Inn.”Now that it is almost time to leave England I am finding the housework less of a

drudgery, Also, as it is school holiday time, Jim and Henry are able to go on walks with

the older children and so use up some of their surplus energy. Cath and I took the

children (except young George who went rabbit shooting with his uncle Reg, and

Henry, who stayed at home with his dad) to the Wakes at Selston, the neighbouring

village. There were the roundabouts and similar contraptions but the side shows had

more appeal for the children. Ann and Kate found a stall where assorted prizes were

spread out on a sloping table. Anyone who could land a penny squarely on one of

these objects was given a similar one as a prize.I was touched to see that both girls ignored all the targets except a box of fifty

cigarettes which they were determined to win for me. After numerous attempts, Kate

landed her penny successfully and you would have loved to have seen her radiant little

face.Eleanor.

Dar es Salaam 22nd October 1946

Dearest Family.

Back in Tanganyika at last, but not together. We have to stay in Dar es Salaam

until tomorrow when the train leaves for Dodoma. We arrived yesterday morning to find

all the hotels filled with people waiting to board ships for England. Fortunately some

friends came to the rescue and Ann, Kate and John have gone to stay with them. Jim,

Henry and I are sleeping in a screened corner of the lounge of the New Africa Hotel, and

George and young George have beds in the Palm Court of the same hotel.We travelled out from England in the Winchester Castle under troopship

conditions. We joined her at Southampton after a rather slow train journey from

Nottingham. We arrived after dark and from the station we could see a large ship in the

docks with a floodlit red funnel. “Our ship,” yelled the children in delight, but it was not the

Winchester Castle but the Queen Elizabeth, newly reconditioned.We had hoped to board our ship that evening but George made enquiries and

found that we would not be allowed on board until noon next day. Without much hope,

we went off to try to get accommodation for eight at a small hotel recommended by the

taxi driver. Luckily for us there was a very motherly woman at the reception desk. She

looked in amusement at the six children and said to me, “Goodness are all these yours,

ducks? Then she called over her shoulder, “Wilf, come and see this lady with lots of

children. We must try to help.” They settled the problem most satisfactorily by turning

two rooms into a dormitory.In the morning we had time to inspect bomb damage in the dock area of

Southampton. Most of the rubble had been cleared away but there are still numbers of

damaged buildings awaiting demolition. A depressing sight. We saw the Queen Mary

at anchor, still in her drab war time paint, but magnificent nevertheless.

The Winchester Castle was crammed with passengers and many travelled in

acute discomfort. We were luckier than most because the two girls, the three small boys

and I had a stateroom to ourselves and though it was stripped of peacetime comforts,

we had a private bathroom and toilet. The two Georges had bunks in a huge men-only

dormitory somewhere in the bowls of the ship where they had to share communal troop

ship facilities. The food was plentiful but unexciting and one had to queue for afternoon

tea. During the day the decks were crowded and there was squatting room only. The

many children on board got bored.Port Said provided a break and we were all entertained by the ‘Gully Gully’ man

and his conjuring tricks, and though we had no money to spend at Simon Artz, we did at

least have a chance to stretch our legs. Next day scores of passengers took ill with

sever stomach upsets, whether from food poisoning, or as was rumoured, from bad

water taken on at the Egyptian port, I don’t know. Only the two Georges in our family

were affected and their attacks were comparatively mild.As we neared the Kenya port of Mombassa, the passengers for Dar es Salaam

were told that they would have to disembark at Mombassa and continue their journey in

a small coaster, the Al Said. The Winchester Castle is too big for the narrow channel

which leads to Dar es Salaam harbour.From the wharf the Al Said looked beautiful. She was once the private yacht of

the Sultan of Zanzibar and has lovely lines. Our admiration lasted only until we were

shown our cabins. With one voice our children exclaimed, “Gosh they stink!” They did, of

a mixture of rancid oil and sweat and stale urine. The beds were not yet made and the

thin mattresses had ominous stains on them. John, ever fastidious, lifted his mattress and two enormous cockroaches scuttled for cover.We had a good homely lunch served by two smiling African stewards and

afterwards we sat on deck and that was fine too, though behind ones enjoyment there

was the thought of those stuffy and dirty cabins. That first night nearly everyone,

including George and our older children, slept on deck. Women occupied deck chairs

and men and children slept on the bare decks. Horrifying though the idea was, I decided

that, as Jim had a bad cough, he, Henry and I would sleep in our cabin.When I announced my intention of sleeping in the cabin one of the passengers

gave me some insecticide spray which I used lavishly, but without avail. The children

slept but I sat up all night with the light on, determined to keep at least their pillows clear

of the cockroaches which scurried about boldly regardless of the light. All the next day

and night we avoided the cabins. The Al Said stopped for some hours at Zanzibar to

offload her deck cargo of live cattle and packing cases from the hold. George and the

elder children went ashore for a walk but I felt too lazy and there was plenty to watch

from deck.That night I too occupied a deck chair and slept quite comfortably, and next

morning we entered the palm fringed harbour of Dar es Salaam and were home.Eleanor.

Mbeya 1st November 1946

Dearest Family.

Home at last! We are all most happily installed in a real family house about three

miles out of Mbeya and near the school. This house belongs to an elderly German and

has been taken over by the Custodian of Enemy Property and leased to the

Government.The owner, whose name is Shenkel, was not interned but is allowed to occupy a

smaller house on the Estate. I found him in the garden this morning lecturing the children

on what they may do and may not do. I tried to make it quite clear to him that he was not

our landlord, though he clearly thinks otherwise. After he had gone I had to take two

aspirin and lie down to recover my composure! I had been warned that he has this effect

on people.Mr Shenkel is a short and ugly man, his clothes are stained with food and he

wears steel rimmed glasses tied round his head with a piece of dirty elastic because

one earpiece is missing. He speaks with a thick German accent but his English is fluent

and I believe he is a cultured and clever man. But he is maddening. The children were

more amused than impressed by his exhortations and have happily Christened our

home, ‘Old Shenks’.The house has very large grounds as the place is really a derelict farm. It suits us

down to the ground. We had no sooner unpacked than George went off on safari after

those maneating lions in the Njombe District. he accounted for one, and a further two

jointly with a Game Scout, before we left for England. But none was shot during the five

months we were away as George’s relief is quite inexperienced in such work. George

thinks that there are still about a dozen maneaters at large. His theory is that a female

maneater moved into the area in 1938 when maneating first started, and brought up her

cubs to be maneaters, and those cubs in turn did the same. The three maneating lions

that have been shot were all in very good condition and not old and maimed as

maneaters usually are.George anticipates that it will be months before all these lions are accounted for

because they are constantly on the move and cover a very large area. The lions have to

be hunted on foot because they range over broken country covered by bush and fairly

dense thicket.I did a bit of shooting myself yesterday and impressed our African servants and

the children and myself. What a fluke! Our houseboy came to say that there was a snake

in the garden, the biggest he had ever seen. He said it was too big to kill with a stick and

would I shoot it. I had no gun but a heavy .450 Webley revolver and I took this and

hurried out with the children at my heels.The snake turned out to be an unusually large puff adder which had just shed its

skin. It looked beautiful in a repulsive way. So flanked by servants and children I took

aim and shot, not hitting the head as I had planned, but breaking the snake’s back with

the heavy bullet. The two native boys then rushed up with sticks and flattened the head.

“Ma you’re a crack shot,” cried the kids in delighted surprise. I hope to rest on my laurels

for a long, long while.Although there are only a few weeks of school term left the four older children will

start school on Monday. Not only am I pleased with our new home here but also with

the staff I have engaged. Our new houseboy, Reuben, (but renamed Robin by our

children) is not only cheerful and willing but intelligent too, and Jumbe, the wood and

garden boy, is a born clown and a source of great entertainment to the children.I feel sure that we are all going to be very happy here at ‘Old Shenks!.

Eleanor.

February 2, 2022 at 12:33 pm #6266In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 7

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Oldeani Hospital. 19th September 1938

Dearest Family,

George arrived today to take us home to Mbulu but Sister Marianne will not allow

me to travel for another week as I had a bit of a set back after baby’s birth. At first I was

very fit and on the third day Sister stripped the bed and, dictionary in hand, started me

off on ante natal exercises. “Now make a bridge Mrs Rushby. So. Up down, up down,’

whilst I obediently hoisted myself aloft on heels and head. By the sixth day she

considered it was time for me to be up and about but alas, I soon had to return to bed

with a temperature and a haemorrhage. I got up and walked outside for the first time this

morning.I have had lots of visitors because the local German settlers seem keen to see

the first British baby born in the hospital. They have been most kind, sending flowers

and little German cards of congratulations festooned with cherubs and rather sweet. Most

of the women, besides being pleasant, are very smart indeed, shattering my illusion that

German matrons are invariably fat and dowdy. They are all much concerned about the

Czecko-Slovakian situation, especially Sister Marianne whose home is right on the

border and has several relations who are Sudentan Germans. She is ant-Nazi and

keeps on asking me whether I think England will declare war if Hitler invades Czecko-

Slovakia, as though I had inside information.George tells me that he has had a grass ‘banda’ put up for us at Mbulu as we are

both determined not to return to those prison-like quarters in the Fort. Sister Marianne is

horrified at the idea of taking a new baby to live in a grass hut. She told George,

“No,No,Mr Rushby. I find that is not to be allowed!” She is an excellent Sister but rather

prim and George enjoys teasing her. This morning he asked with mock seriousness,

“Sister, why has my wife not received her medal?” Sister fluttered her dictionary before

asking. “What medal Mr Rushby”. “Why,” said George, “The medal that Hitler gives to

women who have borne four children.” Sister started a long and involved explanation

about the medal being only for German mothers whilst George looked at me and

grinned.Later. Great Jubilation here. By the noise in Sister Marianne’s sitting room last night it

sounded as though the whole German population had gathered to listen to the wireless

news. I heard loud exclamations of joy and then my bedroom door burst open and

several women rushed in. “Thank God “, they cried, “for Neville Chamberlain. Now there

will be no war.” They pumped me by the hand as though I were personally responsible

for the whole thing.George on the other hand is disgusted by Chamberlain’s lack of guts. Doesn’t

know what England is coming to these days. I feel too content to concern myself with

world affairs. I have a fine husband and four wonderful children and am happy, happy,

happy.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 30th September 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are, comfortably installed in our little green house made of poles and

rushes from a nearby swamp. The house has of course, no doors or windows, but

there are rush blinds which roll up in the day time. There are two rooms and a little porch

and out at the back there is a small grass kitchen.Here we have the privacy which we prize so highly as we are screened on one

side by a Forest Department plantation and on the other three sides there is nothing but

the rolling countryside cropped bare by the far too large herds of cattle and goats of the

Wambulu. I have a lovely lazy time. I still have Kesho-Kutwa and the cook we brought

with us from the farm. They are both faithful and willing souls though not very good at

their respective jobs. As one of these Mbeya boys goes on safari with George whose

job takes him from home for three weeks out of four, I have taken on a local boy to cut

firewood and heat my bath water and generally make himself useful. His name is Saa,

which means ‘Clock’We had an uneventful but very dusty trip from Oldeani. Johnny Jo travelled in his

pram in the back of the boxbody and got covered in dust but seems none the worst for

it. As the baby now takes up much of my time and Kate was showing signs of

boredom, I have engaged a little African girl to come and play with Kate every morning.

She is the daughter of the head police Askari and a very attractive and dignified little

person she is. Her name is Kajyah. She is scrupulously clean, as all Mohammedan

Africans seem to be. Alas, Kajyah, though beautiful, is a bore. She simply does not

know how to play, so they just wander around hand in hand.There are only two drawbacks to this little house. Mbulu is a very windy spot so

our little reed house is very draughty. I have made a little tent of sheets in one corner of

the ‘bedroom’ into which I can retire with Johnny when I wish to bathe or sponge him.

The other drawback is that many insects are attracted at night by the lamp and make it

almost impossible to read or sew and they have a revolting habit of falling into the soup.

There are no dangerous wild animals in this area so I am not at all nervous in this

flimsy little house when George is on safari. Most nights hyaenas come around looking

for scraps but our dogs, Fanny and Paddy, soon see them off.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 25th October 1938

Dearest Family,

Great news! a vacancy has occurred in the Game Department. George is to

transfer to it next month. There will be an increase in salary and a brighter prospect for

the future. It will mean a change of scene and I shall be glad of that. We like Mbulu and

the people here but the rains have started and our little reed hut is anything but water

tight.Before the rain came we had very unpleasant dust storms. I think I told you that

this is a treeless area and the grass which normally covers the veldt has been cropped

to the roots by the hungry native cattle and goats. When the wind blows the dust

collects in tall black columns which sweep across the country in a most spectacular

fashion. One such dust devil struck our hut one day whilst we were at lunch. George

swept Kate up in a second and held her face against his chest whilst I rushed to Johnny

Jo who was asleep in his pram, and stooped over the pram to protect him. The hut

groaned and creaked and clouds of dust blew in through the windows and walls covering

our persons, food, and belongings in a black pall. The dogs food bowls and an empty

petrol tin outside the hut were whirled up and away. It was all over in a moment but you

should have seen what a family of sweeps we looked. George looked at our blackened

Johnny and mimicked in Sister Marianne’s primmest tones, “I find that this is not to be

allowed.”The first rain storm caught me unprepared when George was away on safari. It

was a terrific thunderstorm. The quite violent thunder and lightening were followed by a

real tropical downpour. As the hut is on a slight slope, the storm water poured through

the hut like a river, covering the entire floor, and the roof leaked like a lawn sprinkler.

Johnny Jo was snug enough in the pram with the hood raised, but Kate and I had a

damp miserable night. Next morning I had deep drains dug around the hut and when

George returned from safari he managed to borrow an enormous tarpaulin which is now

lashed down over the roof.It did not rain during the next few days George was home but the very next night

we were in trouble again. I was awakened by screams from Kate and hurriedly turned up

the lamp to see that we were in the midst of an invasion of siafu ants. Kate’s bed was

covered in them. Others appeared to be raining down from the thatch. I quickly stripped

Kate and carried her across to my bed, whilst I rushed to the pram to see whether

Johnny Jo was all right. He was fast asleep, bless him, and slept on through all the

commotion, whilst I struggled to pick all the ants out of Kate’s hair, stopping now and

again to attend to my own discomfort. These ants have a painful bite and seem to

choose all the most tender spots. Kate fell asleep eventually but I sat up for the rest of

the night to make sure that the siafu kept clear of the children. Next morning the servants

dispersed them by laying hot ash.In spite of the dampness of the hut both children are blooming. Kate has rosy

cheeks and Johnny Jo now has a fuzz of fair hair and has lost his ‘old man’ look. He

reminds me of Ann at his age.Eleanor.

Iringa. 30th November 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are back in the Southern Highlands and installed on the second floor of

another German Fort. This one has been modernised however and though not so

romantic as the Mbulu Fort from the outside, it is much more comfortable.We are all well

and I am really proud of our two safari babies who stood up splendidly to a most trying

journey North from Mbulu to Arusha and then South down the Great North Road to

Iringa where we expect to stay for a month.At Arusha George reported to the headquarters of the Game Department and

was instructed to come on down here on Rinderpest Control. There is a great flap on in

case the rinderpest spread to Northern Rhodesia and possibly onwards to Southern

Rhodesia and South Africa. Extra veterinary officers have been sent to this area to

inoculate all the cattle against the disease whilst George and his African game Scouts will

comb the bush looking for and destroying diseased game. If the rinderpest spreads,

George says it may be necessary to shoot out all the game in a wide belt along the

border between the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika and Northern Rhodesia, to

prevent the disease spreading South. The very idea of all this destruction sickens us

both.George left on a foot safari the day after our arrival and I expect I shall be lucky if I

see him occasionally at weekends until this job is over. When rinderpest is under control

George is to be stationed at a place called Nzassa in the Eastern Province about 18

miles from Dar es Salaam. George’s orderly, who is a tall, cheerful Game Scout called

Juma, tells me that he has been stationed at Nzassa and it is a frightful place! However I

refuse to be depressed. I now have the cheering prospect of leave to England in thirty

months time when we will be able to fetch Ann and George and be a proper family

again. Both Ann and George look happy in the snapshots which mother-in-law sends

frequently. Ann is doing very well at school and loves it.To get back to our journey from Mbulu. It really was quite an experience. It

poured with rain most of the way and the road was very slippery and treacherous the

120 miles between Mbulu and Arusha. This is a little used earth road and the drains are

so blocked with silt as to be practically non existent. As usual we started our move with

the V8 loaded to capacity. I held Johnny on my knee and Kate squeezed in between

George and me. All our goods and chattels were in wooden boxes stowed in the back

and the two houseboys and the two dogs had to adjust themselves to the space that

remained. We soon ran into trouble and it took us all day to travel 47 miles. We stuck

several times in deep mud and had some most nasty skids. I simply clutched Kate in

one hand and Johnny Jo in the other and put my trust in George who never, under any

circumstances, loses his head. Poor Johnny only got his meals when circumstances

permitted. Unfortunately I had put him on a bottle only a few days before we left Mbulu

and, as I was unable to buy either a primus stove or Thermos flask there we had to

make a fire and boil water for each meal. Twice George sat out in the drizzle with a rain

coat rapped over his head to protect a miserable little fire of wet sticks drenched with

paraffin. Whilst we waited for the water to boil I pacified John by letting him suck a cube

of Tate and Lyles sugar held between my rather grubby fingers. Not at all according to

the book.That night George, the children and I slept in the car having dumped our boxes

and the two servants in a deserted native hut. The rain poured down relentlessly all night

and by morning the road was more of a morass than ever. We swerved and skidded

alarmingly till eventually one of the wheel chains broke and had to be tied together with

string which constantly needed replacing. George was so patient though he was wet

and muddy and tired and both children were very good. Shortly before reaching the Great North Road we came upon Jack Gowan, the Stock Inspector from Mbulu. His car