-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 11, 2023 at 11:53 pm #6372

In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

5 important keywords linked to Badul

- Action-space-time

- Harmonic fluid

- Rhythm

- Scale

- Choosing without limits.

Imagine four friends, Jib, Franci, Tracy, and Eric, who are all deeply connected through their shared passion for music and performance. They often spend hours together creating and experimenting with different sounds and rhythms.

One day, as they were playing together, they found that their combined energy had created a new essence, which they named Badul. This new essence was formed from the unique combination of their individual energies and personalities, and it quickly grew in autonomy and began to explore the world around it.

As Badul began to explore, it discovered that it had the ability to understand and create complex rhythms, and that it could use this ability to bring people together and help them find a sense of connection and purpose.

As Badul traveled, it would often come across individuals who were struggling to find their way in life. It would use its ability to create rhythm and connection to help these individuals understand themselves better and make the choices that were right for them.

In the scene, Badul is exploring a city, playing with the rhythms of the city, through the traffic, the steps of people, the ambiance. Badul would observe a person walking in the streets, head down, lost in thoughts. Badul would start playing a subtle tune, and as the person hears it, starts to walk with the rhythm, head up, starting to smile.

As the person continues to walk and follow the rhythm created by Badul, he begins to notice things he had never noticed before and begins to feel a sense of connection to the world around him. The music created by Badul serves as a guide, helping the person to understand himself and make the choices that will lead to a happier, more fulfilled life.

In this way, Badul’s focus is to bring people together, to connect them to themselves and to the world around them through the power of rhythm and music, and to be an ally in the search of personal revelation and understanding.

January 11, 2023 at 10:32 pm #6368In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Something in the style of FPooh:

Arona heard the music growing louder as she approached the source of the sound. She could see a group of people gathered around a large fire, the flickering light casting shadows on the faces of the dancers. She hesitated for a moment, remembering the isolation of her journey and wondering if she was ready to be among people again. But the music was too inviting, and she found herself drawn towards the group.

As she neared the fire, she saw a young man playing a flute, the music flowing from his fingers with a fluid grace that captivated her. He looked up as she approached, and their eyes met. She could see the surprise and curiosity in his gaze, and she smiled, feeling a sense of connection she had not felt in a long time.

Fiona was sitting on a bench in the park, watching the children play. She had brought her sketchbook with her, but for once she didn’t feel the urge to draw. Instead she watched the children’s laughter, feeling content and at peace. Suddenly, she saw a young girl running towards her, a look of pure joy on her face. The girl stopped in front of her and held out a flower, offering it to Fiona with a smile.

Taken aback, Fiona took the flower and thanked the girl. The girl giggled and ran off to join her friends. Fiona looked down at the flower in her hand, and she felt a sense of inspiration, like a spark igniting within her. She opened her sketchbook and began to draw, feeling the weight lift from her shoulders and the magic of creativity flowing through her.

Minky led the group of misfits towards the emporium, his bowler hat bobbing on his head. He chattered excitedly, telling stories of the wondrous items to be found within Mr Jib’s store. Yikesy followed behind, still lost in his thoughts of Arona and feeling a sense of dread at the thought of buying a bowler hat. The green fairy flitted along beside him, her wings a blur of movement as she chattered with the parrot perched on her shoulder.

As they reached the emporium, they were disappointed to find it closed. But Minky refused to be discouraged, and he led them to a nearby cafe where they could sit and enjoy some tea and cake while they wait for the emporium to open. The green fairy was delighted, and she ordered a plate of macarons, smiling as she tasted the sweetness of the confections.

About creativity & everyday magic

Fiona had always been drawn to the magic of creativity, the way a blank page could be transformed into a world of wonder and beauty. But lately, she had been feeling stuck, unable to find the spark that ignited her imagination. She would sit with her sketchbook, pencil in hand, and nothing would come to her.

She started to question her abilities, wondering if she had lost the magic of her art. She spent long hours staring at her blank pages, feeling a weight on her chest that seemed to be growing heavier every day.

But then she remembered the green fairy’s tears and Yikesy’s longing for Arona, and she realized that the magic of creativity wasn’t something that could be found only in art. It was all around her, in the everyday moments of life.

She started to look for the magic in the small things, like the way the sunlight filtered through the trees, or the way a child’s laughter could light up a room. She found it in the way a stranger’s smile could lift her spirits, and in the way a simple cup of tea could bring her comfort.

And as she started to see the magic in the everyday, she found that the weight on her chest lifted and the spark of inspiration returned. She picked up her pencil and began to draw, feeling the magic flowing through her once again.

She understand that creativity blocks aren’t a destination, but just a step, just like the bowler hat that Minky had bought for them all, a bit of everyday magic, nothing too fancy but a sense of belonging, a sense of who they are and where they are going. And she let her pencil flow, with the hopes that one day, they will all find their way home.

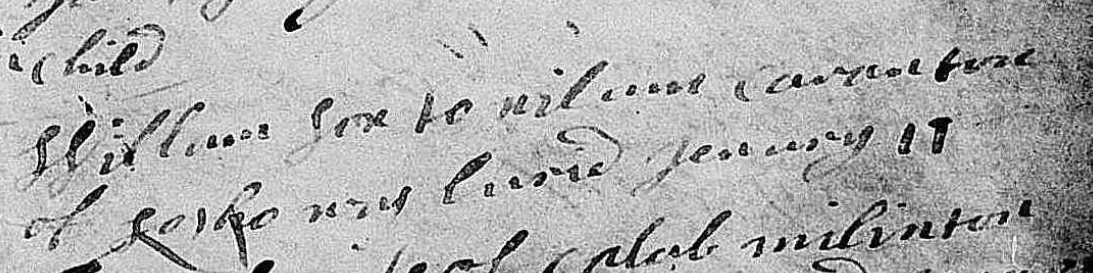

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

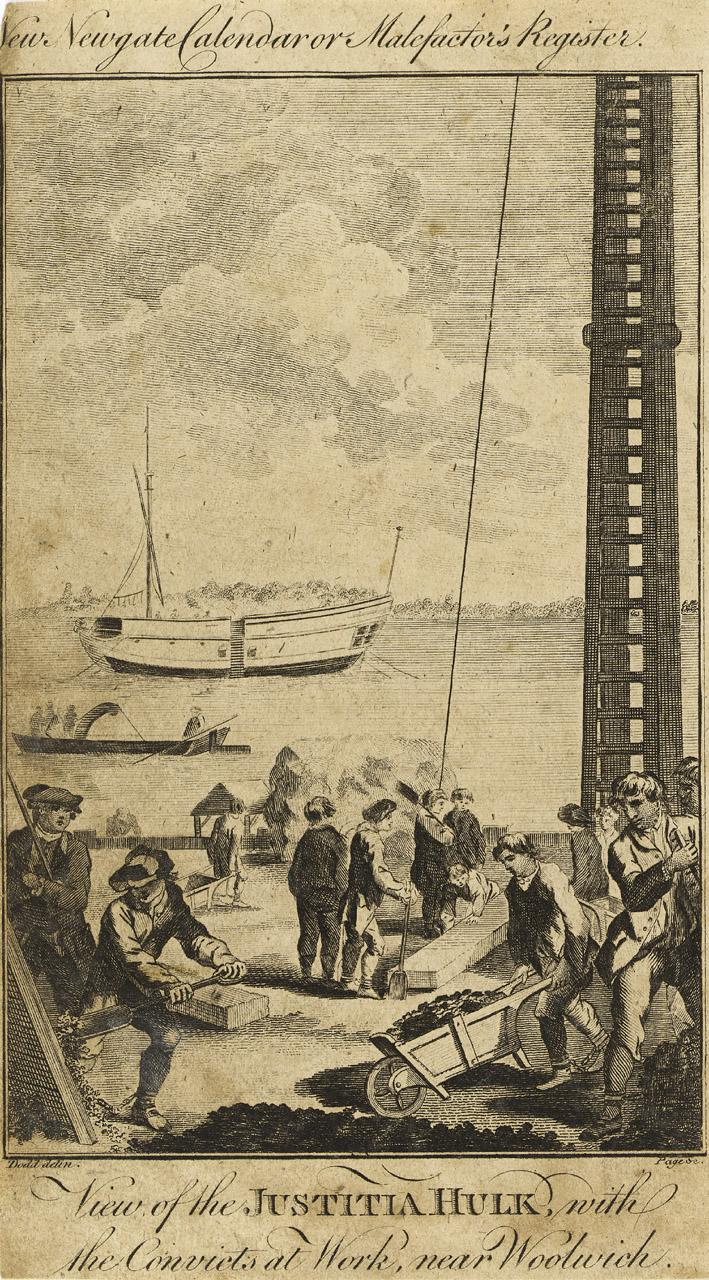

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

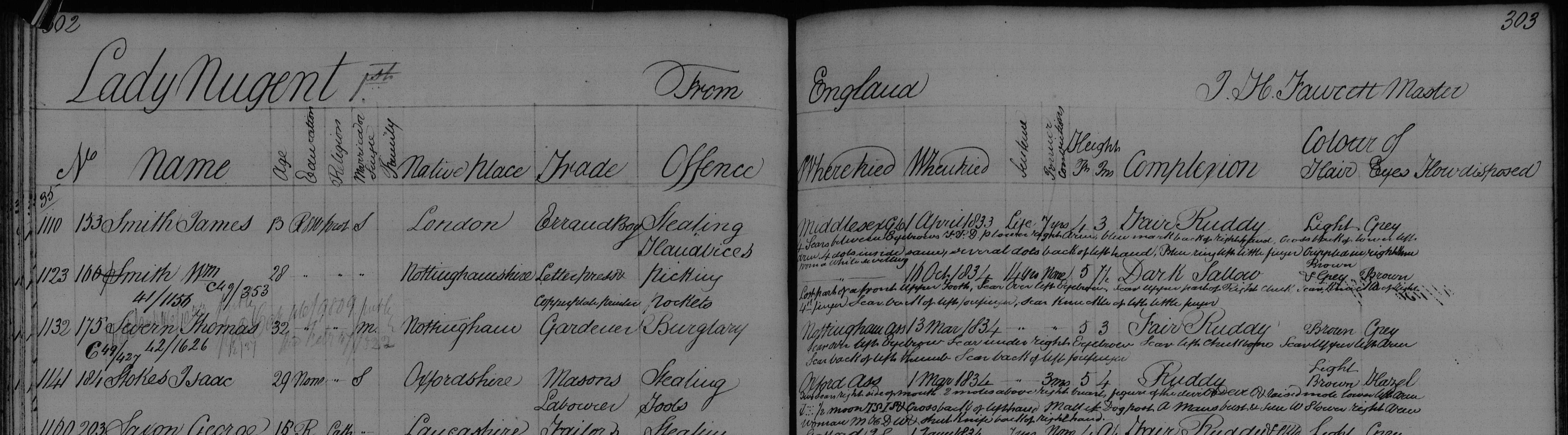

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

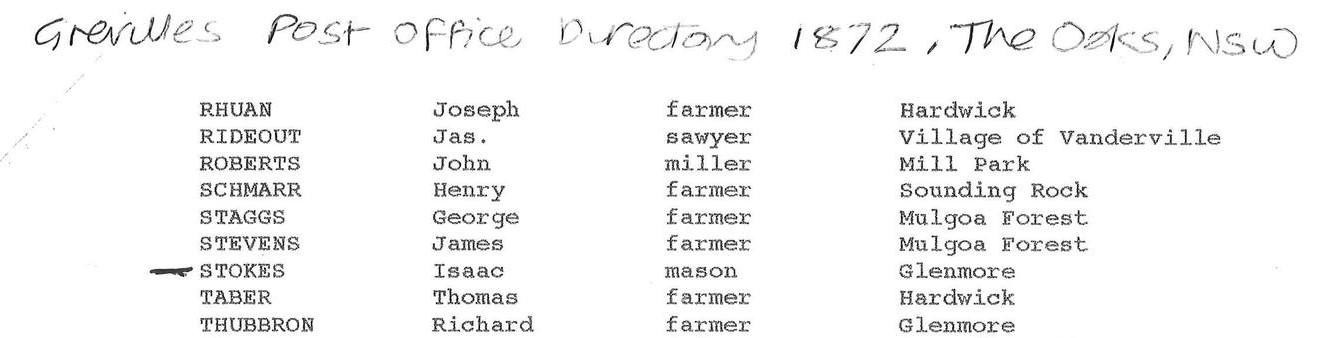

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

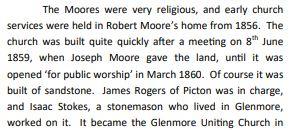

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

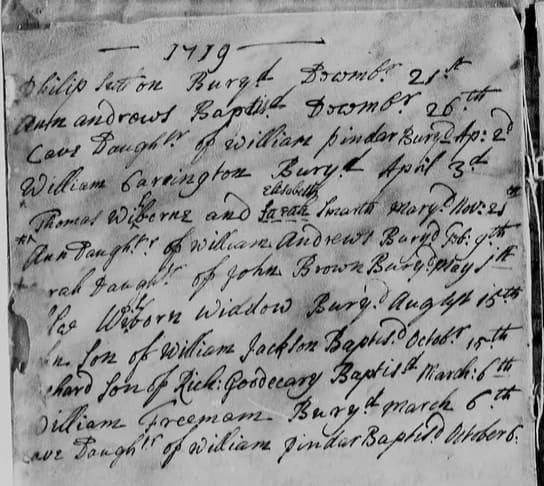

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

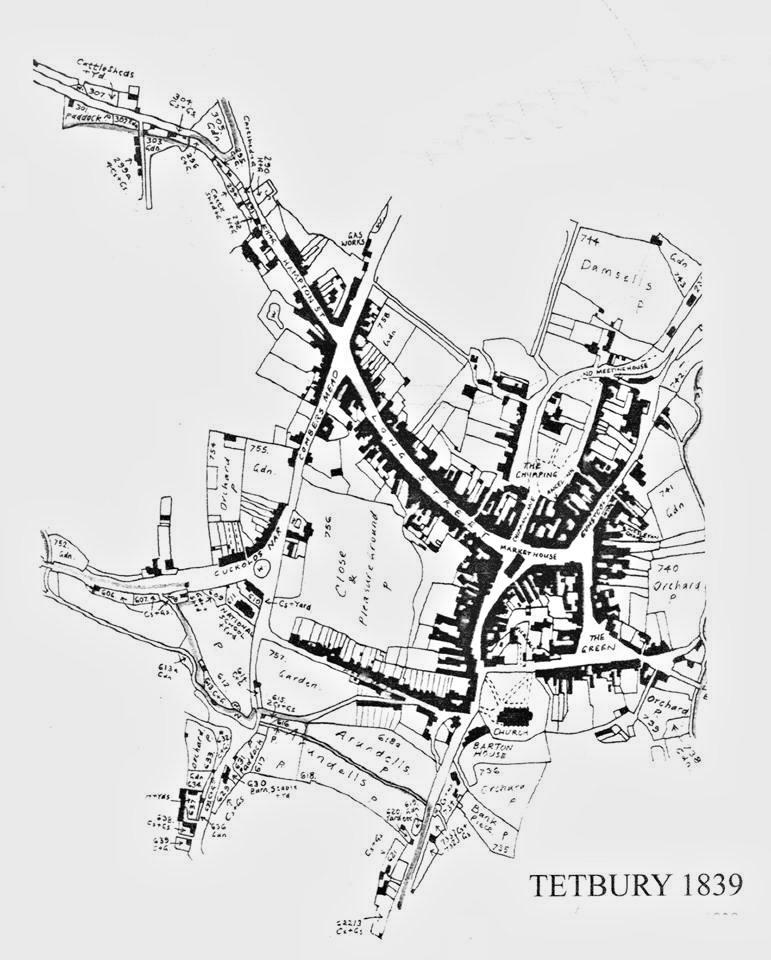

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

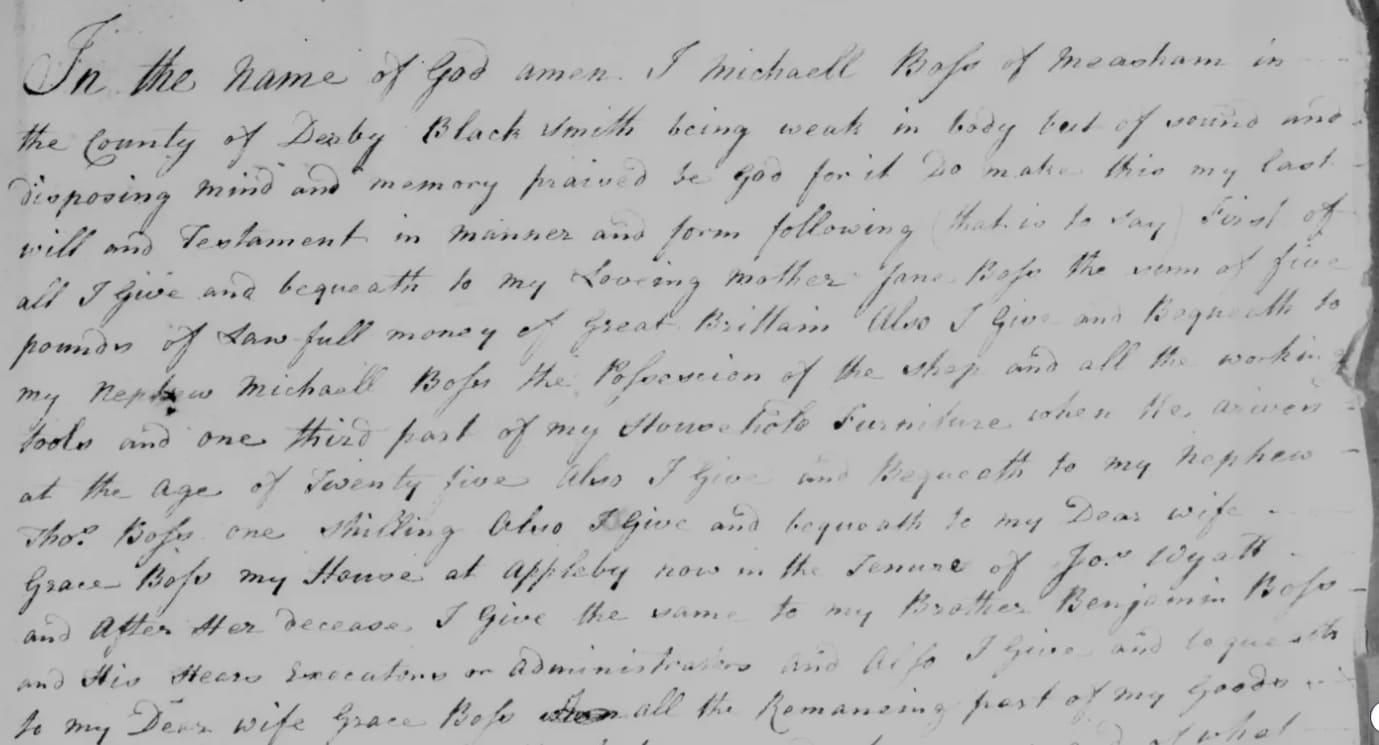

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

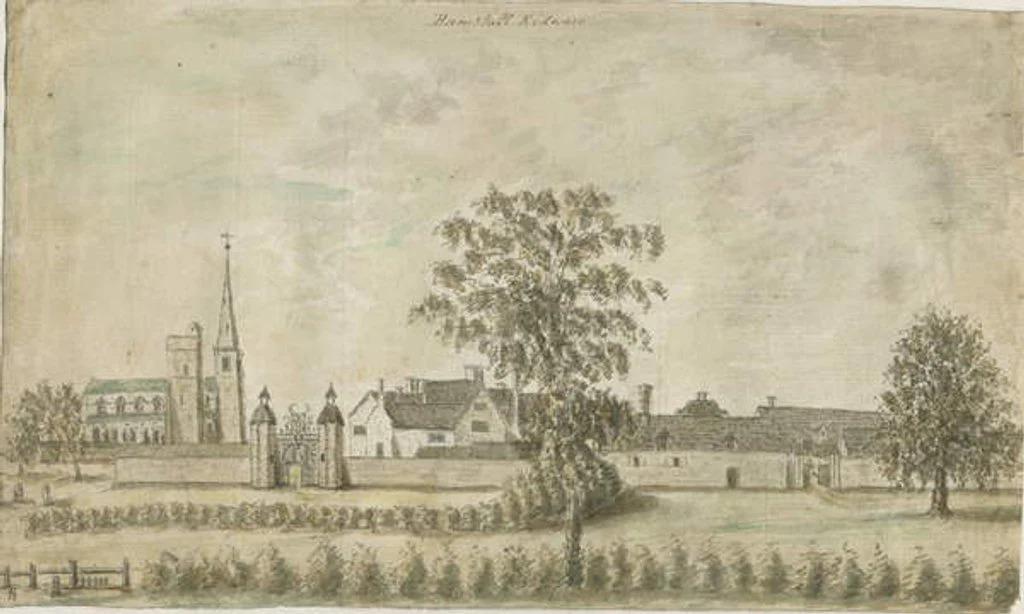

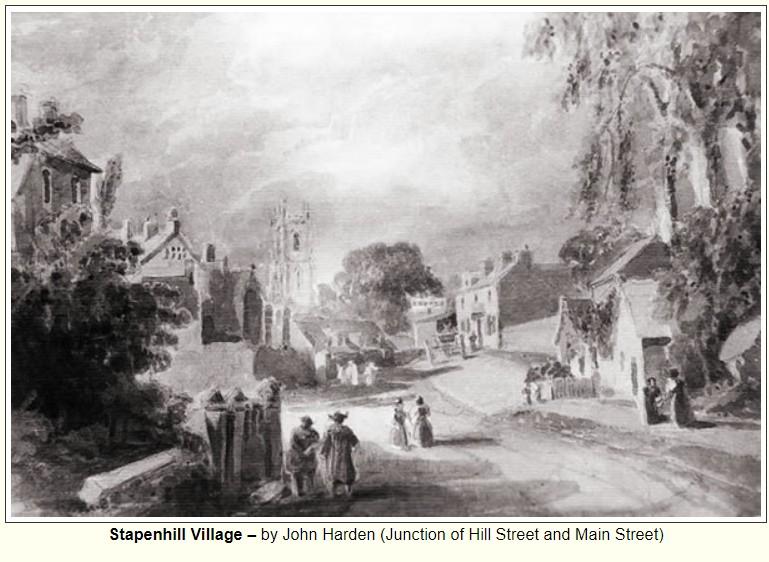

The Hamstall Ridware Connection

Stubbs and Woods

Hamstall Ridware

Hamstall RidwareCharles Tomlinson‘s (1847-1907) wife Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs (1819-1880), born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs.

Solomon Stubbs (1781-1857) was born in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the son of Samuel and Rebecca. Samuel Stubbs (1743-) and Rebecca Wood (1754-) married in 1769 in Darlaston. Samuel and Rebecca had six other children, all born in Darlaston. Sadly four of them died in infancy. Son John was born in 1779 in Darlaston and died two years later in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the same year that Solomon was born there.

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware?

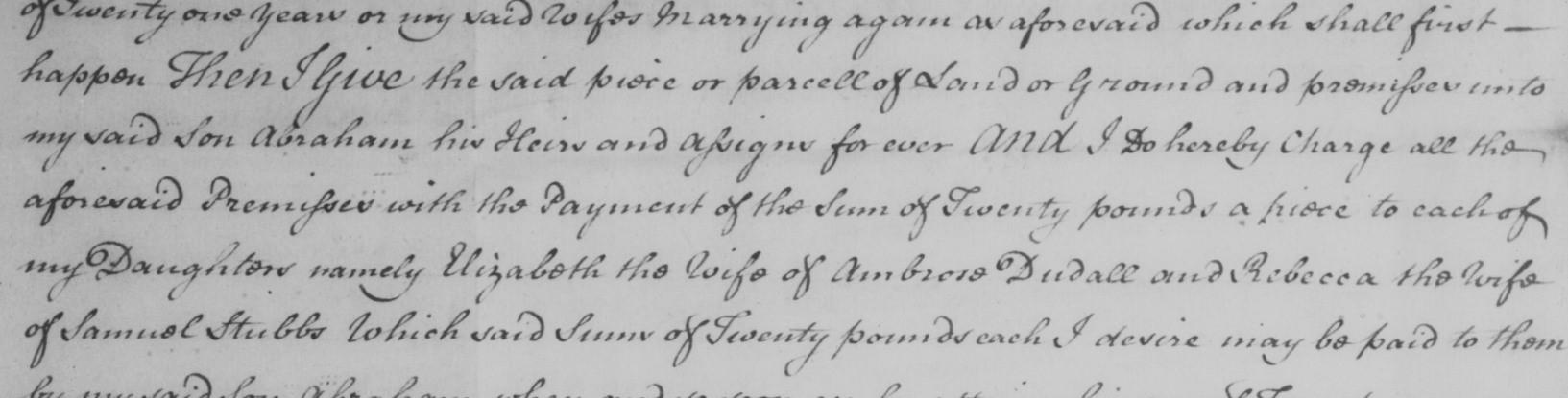

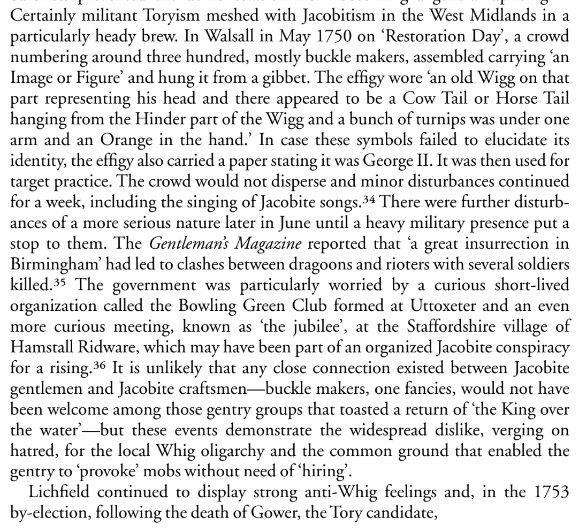

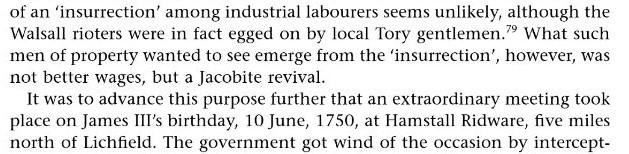

Samuel Stubbs was born in 1743 in Curdworth, Warwickshire (near to Birmingham). I had made a mistake on the tree (along with all of the public trees on the Ancestry website) and had Rebecca Wood born in Cheddleton, Staffordshire. Rebecca Wood from Cheddleton was also born in 1843, the right age for the marriage. The Rebecca Wood born in Darlaston in 1754 seemed too young, at just fifteen years old at the time of the marriage. I couldn’t find any explanation for why a woman from Cheddleton would marry in Darlaston and then move to Hamstall Ridware. People didn’t usually move around much other than intermarriage with neighbouring villages, especially women. I had a closer look at the Darlaston Rebecca, and did a search on her father William Wood. I found his 1784 will online in which he mentions his daughter Rebecca, wife of Samuel Stubbs. Clearly the right Rebecca Wood was the one born in Darlaston, which made much more sense.

An excerpt from William Wood’s 1784 will mentioning daughter Rebecca married to Samuel Stubbs:

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware circa 1780?

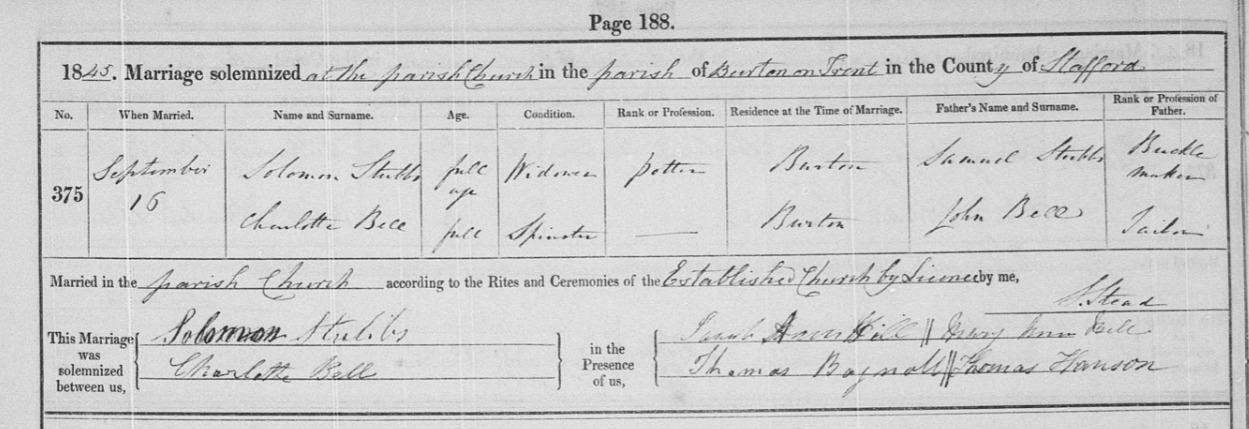

I had not intially noticed that Solomon Stubbs married again the year after his wife Phillis Lomas (1787-1844) died. Solomon married Charlotte Bell in 1845 in Burton on Trent and on the marriage register, Solomon’s father Samuel Stubbs occupation was mentioned: Samuel was a buckle maker.

Marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell, father Samuel Stubbs buckle maker:

A rudimentary search on buckle making in the late 1700s provided a possible answer as to why Samuel and Rebecca left Darlaston in 1781. Shoe buckles had gone out of fashion, and by 1781 there were half as many buckle makers in Wolverhampton as there had been previously.

“Where there were 127 buckle makers at work in Wolverhampton, 68 in Bilston and 58 in Birmingham in 1770, their numbers had halved in 1781.”

via “historywebsite”(museum/metalware/steel)

Steel buckles had been the height of fashion, and the trade became enormous in Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton was a steel working town, renowned for its steel jewellery which was probably of many types. The trade directories show great numbers of “buckle makers”. Steel buckles were predominantly made in Wolverhampton: “from the late 1760s cut steel comes to the fore, from the thriving industry of the Wolverhampton area”. Bilston was also a great centre of buckle making, and other areas included Walsall. (It should be noted that Darlaston, Walsall, Bilston and Wolverhampton are all part of the same area)

In 1860, writing in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School, George Wallis talks about the cut steel industry in Wolverhampton. Referring to “the fine steel workers of the 17th and 18th centuries” he says: “Let them remember that 100 years ago [sc. c. 1760] a large trade existed with France and Spain in the fine steel goods of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, of which the latter were always allowed to be the best both in taste and workmanship. … A century ago French and Spanish merchants had their houses and agencies at Birmingham for the purchase of the steel goods of Wolverhampton…..The Great Revolution in France put an end to the demand for fine steel goods for a time and hostile tariffs finished what revolution began”.

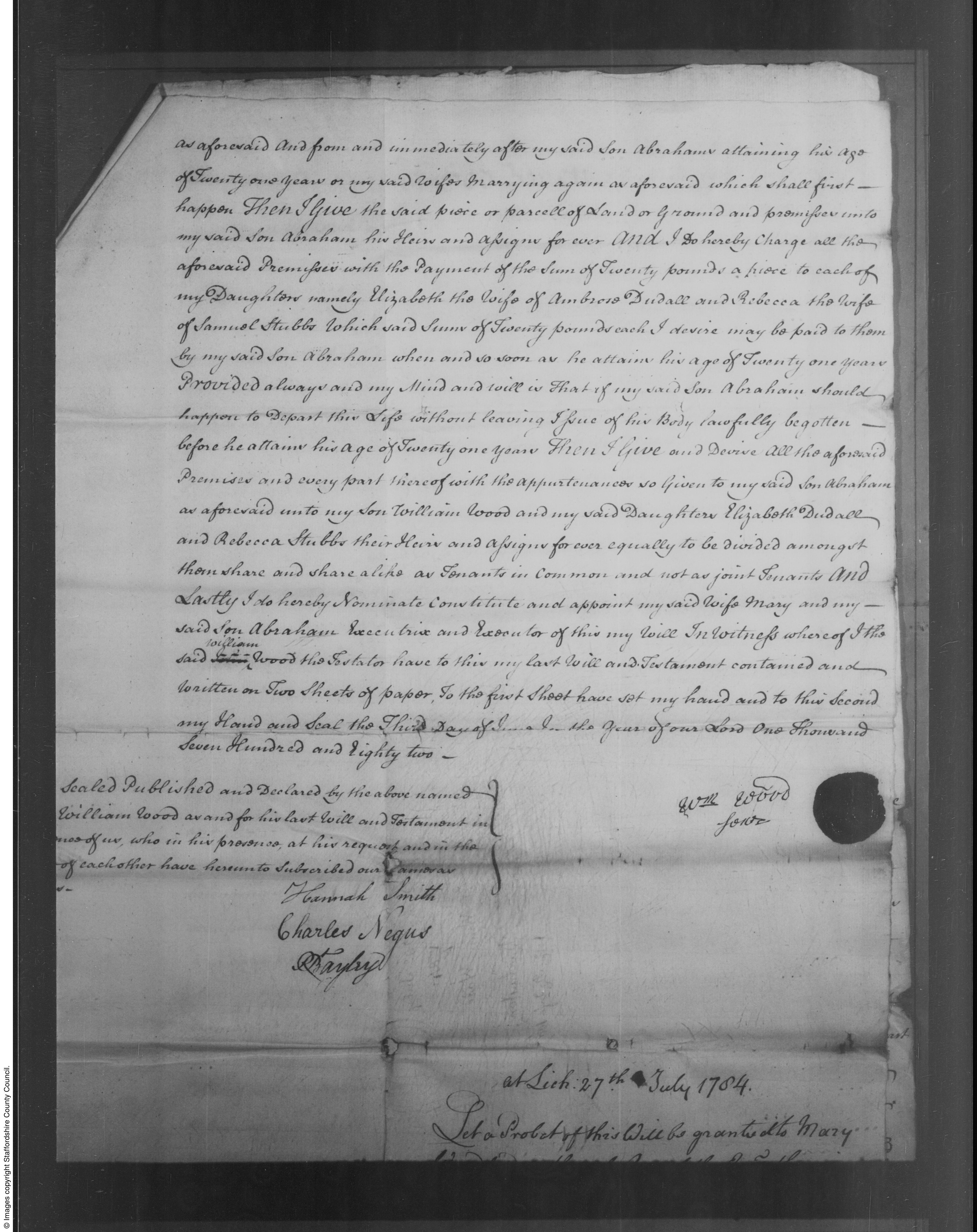

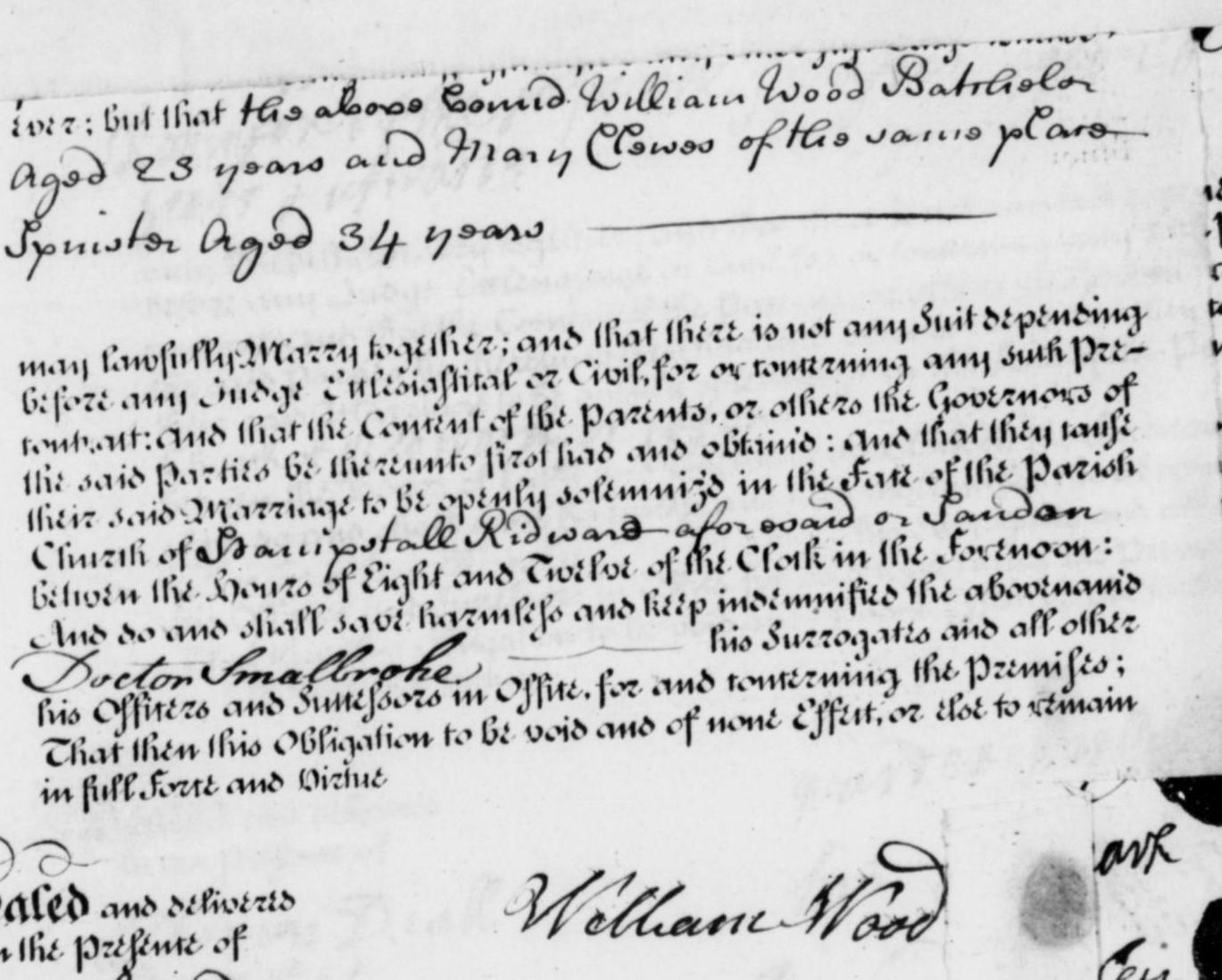

The next search on buckle makers, Wolverhampton and Hamstall Ridware revealed an unexpected connecting link.

In Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall:

In Walsall in 1750 on “Restoration Day” a crowd numbering 300 assembled, mostly buckle makers, singing Jacobite songs and other rebellious and riotous acts. The government was particularly worried about a curious meeting known as the “Jubilee” in Hamstall Ridware, which may have been part of a conspiracy for a Jacobite uprising.

But this was thirty years before Samuel and Rebecca moved to Hamstall Ridware and does not help to explain why they moved there around 1780, although it does suggest connecting links.

Rebecca’s father, William Wood, was a brickmaker. This was stated at the beginning of his will. On closer inspection of the will, he was a brickmaker who owned four acres of brick kilns, as well as dwelling houses, shops, barns, stables, a brewhouse, a malthouse, cattle and land.

A page from the 1784 will of William Wood:

The 1784 will of William Wood of Darlaston:

I William Wood the elder of Darlaston in the county of Stafford, brickmaker, being of sound and disposing mind memory and understanding (praised be to god for the same) do make publish and declare my last will and testament in manner and form following (that is to say) {after debts and funeral expense paid etc} I give to my loving wife Mary the use usage wear interest and enjoyment of all my goods chattels cattle stock in trade ~ money securities for money personal estate and effects whatsoever and wheresoever to hold unto her my said wife for and during the term of her natural life providing she so long continues my widow and unmarried and from or after her decease or intermarriage with any future husband which shall first happen.

Then I give all the said goods chattels cattle stock in trade money securites for money personal estate and effects unto my son Abraham Wood absolutely and forever. Also I give devise and bequeath unto my said wife Mary all that my messuages tenement or dwelling house together with the malthouse brewhouse barn stableyard garden and premises to the same belonging situate and being at Darlaston aforesaid and now in my own possession. Also all that messuage tenement or dwelling house together with the shop garden and premises with the appurtenances to the same ~ belonging situate in Darlaston aforesaid and now in the several holdings or occupation of George Knowles and Edward Knowles to hold the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances to my said wife Mary for and during the term of her natural life provided she so long continues my widow and unmarried. And from or after her decease or intermarriage with a future husband which shall first happen. Then I give and devise the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances unto my said son Abraham Wood his heirs and assigns forever.

Also I give unto my said wife all that piece or parcel of land or ground inclosed and taken out of Heath Field in the parish of Darlaston aforesaid containing four acres or thereabouts (be the same more or less) upon which my brick kilns erected and now in my own possession. To hold unto my said wife Mary until my said son Abraham attains his age of twenty one years if she so long continues my widow and unmarried as aforesaid and from and immediately after my said son Abraham attaining his age of twenty one years or my said wife marrying again as aforesaid which shall first happen then I give the said piece or parcel of land or ground and premises unto my said son Abraham his heirs and assigns forever.

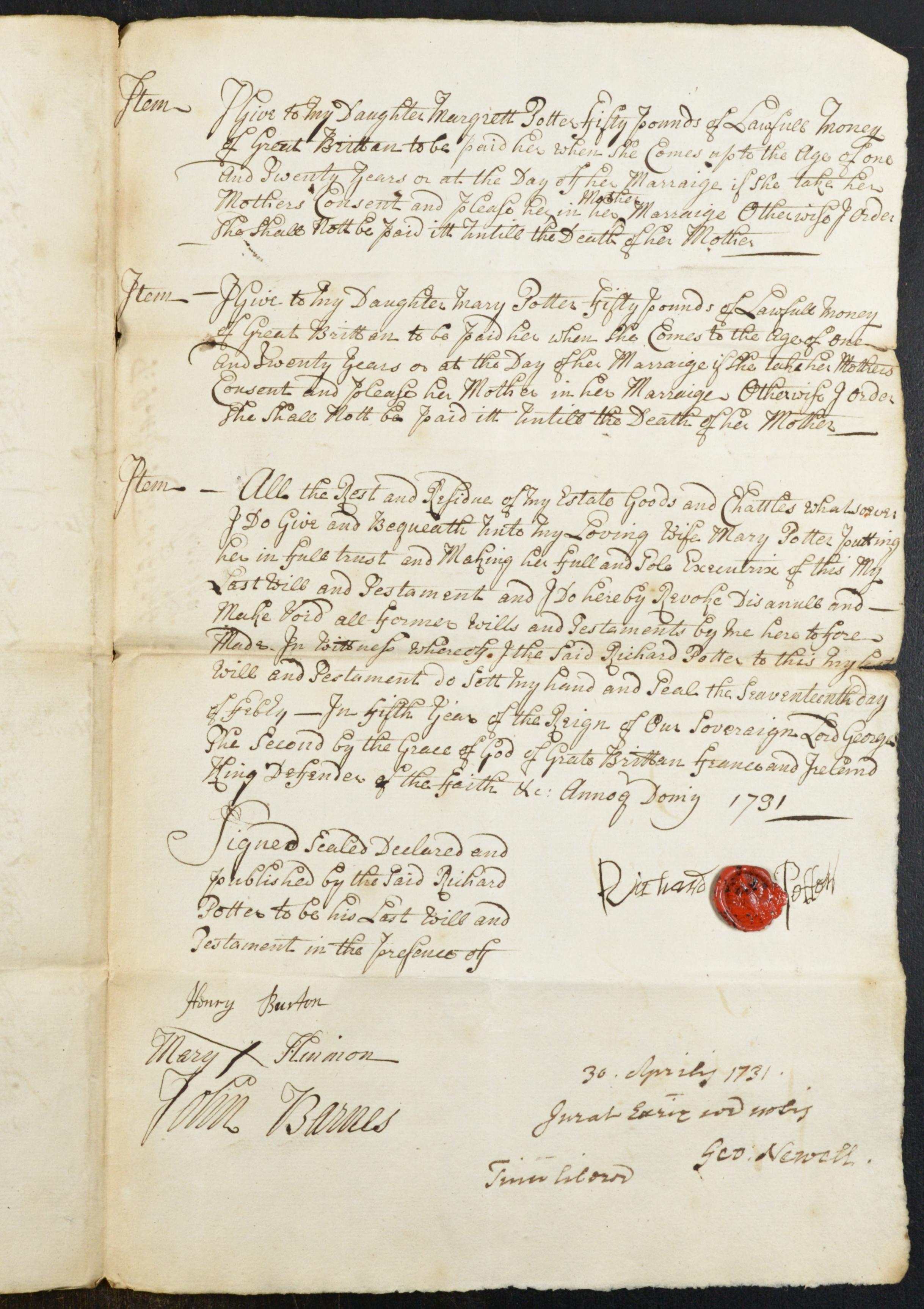

And I do hereby charge all the aforesaid premises with the payment of the sum of twenty pounds a piece to each of my daughters namely Elizabeth the wife of Ambrose Dudall and Rebecca the wife of Samuel Stubbs which said sum of twenty pounds each I devise may be paid to them by my said son Abraham when and so soon as he attains his age of twenty one years provided always and my mind and will is that if my said son Abraham should happen to depart this life without leaving issue of his body lawfully begotten before he attains his age of twenty one years then I give and devise all the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances so given to my said son Abraham as aforesaid unto my said son William Wood and my said daughter Elizabeth Dudall and Rebecca Stubbs their heirs and assigns forever equally divided among them share and share alike as tenants in common and not as joint tenants. And lastly I do hereby nominate constitute and appoint my said wife Mary and my said son Abraham executrix and executor of this my will.

The marriage of William Wood (1725-1784) and Mary Clews (1715-1798) in 1749 was in Hamstall Ridware.

Mary was eleven years Williams senior, and it appears that they both came from Hamstall Ridware and moved to Darlaston after they married. Clearly Rebecca had extended family there (notwithstanding any possible connecting links between the Stubbs buckle makers of Darlaston and the Hamstall Ridware Jacobites thirty years prior). When the buckle trade collapsed in Darlaston, they likely moved to find employment elsewhere, perhaps with the help of Rebecca’s family.

I have not yet been able to find deaths recorded anywhere for either Samuel or Rebecca (there are a couple of deaths recorded for a Samuel Stubbs, one in 1809 in Wolverhampton, and one in 1810 in Birmingham but impossible to say which, if either, is the right one with the limited information, and difficult to know if they stayed in the Hamstall Ridware area or perhaps moved elsewhere)~ or find a reason for their son Solomon to be in Burton upon Trent, an evidently prosperous man with several properties including an earthenware business, as well as a land carrier business.

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

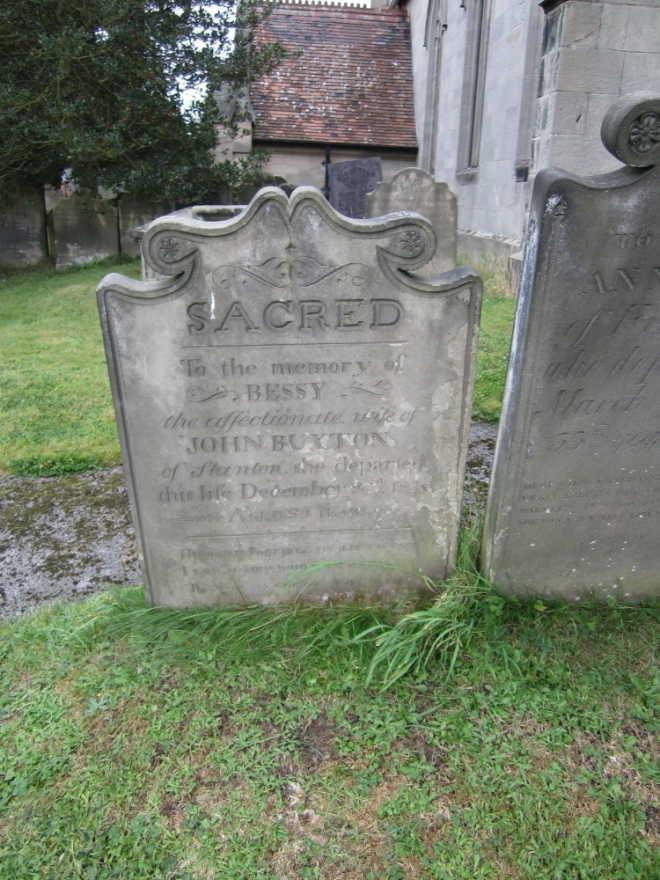

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

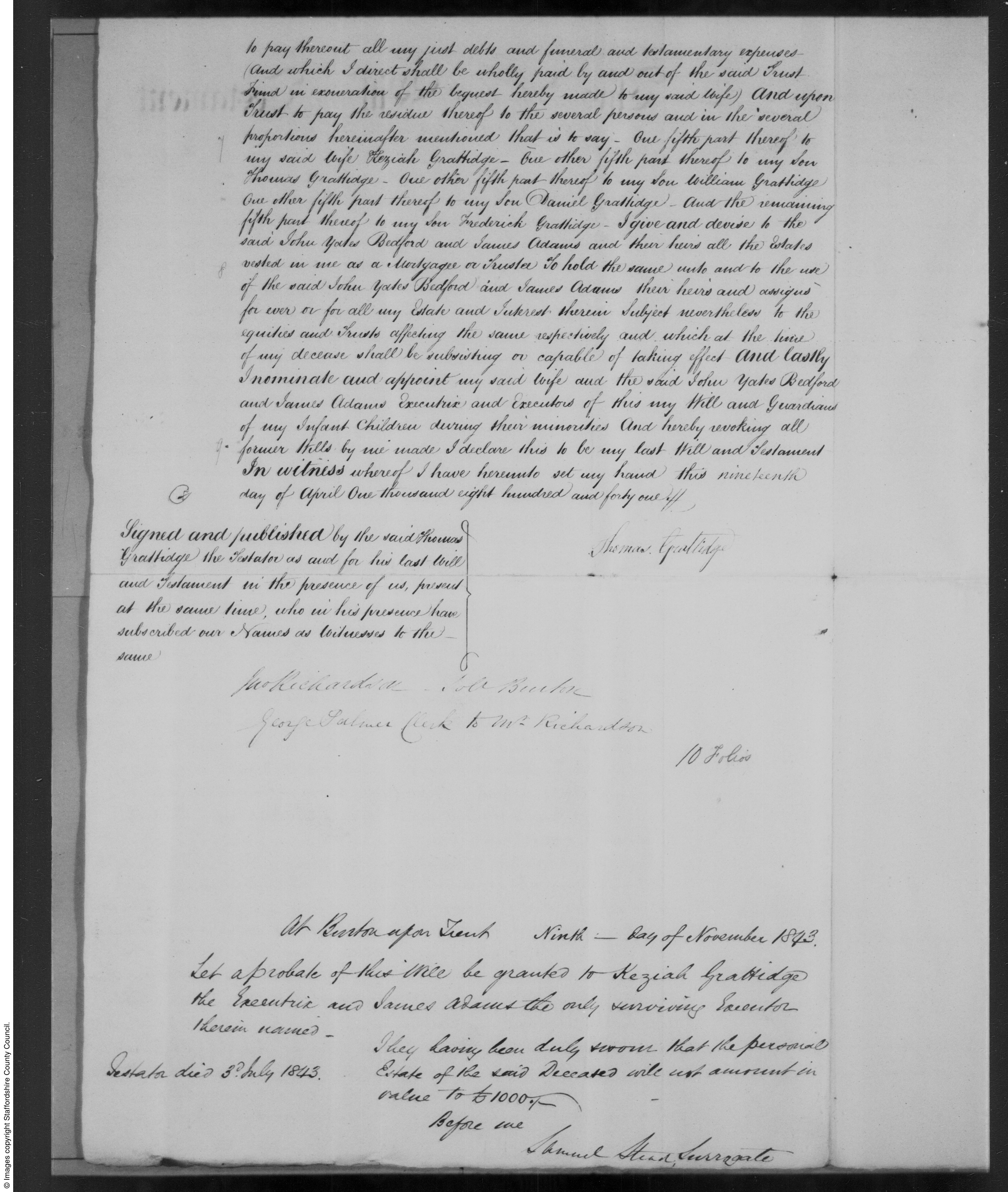

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

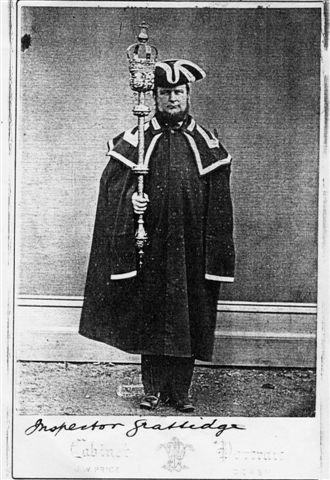

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

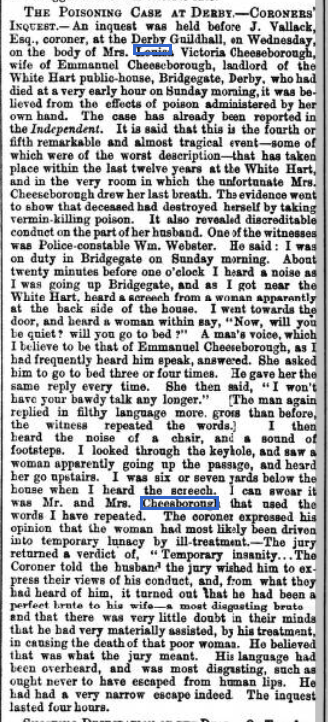

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

August 18, 2022 at 8:26 am #6324

August 18, 2022 at 8:26 am #6324In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

STONE MANOR

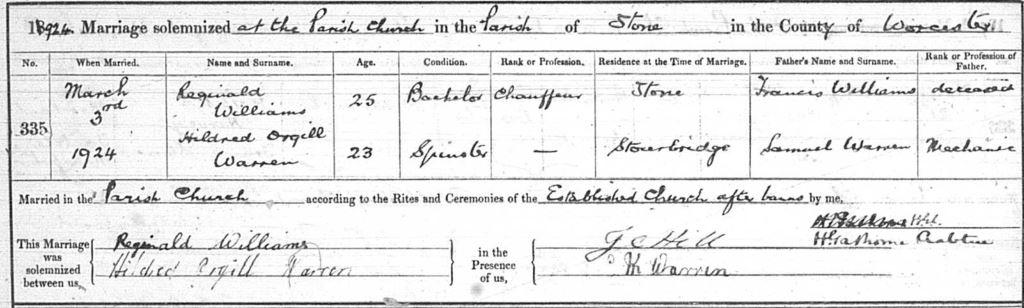

Hildred Orgill Warren born in 1900, my grandmothers sister, married Reginald Williams in Stone, Worcestershire in March 1924. Their daughter Joan was born there in October of that year.

Hildred was a chaffeur on the 1921 census, living at home in Stourbridge with her father (my great grandfather) Samuel Warren, mechanic. I recall my grandmother saying that Hildred was one of the first lady chauffeurs. On their wedding certificate, Reginald is also a chauffeur.

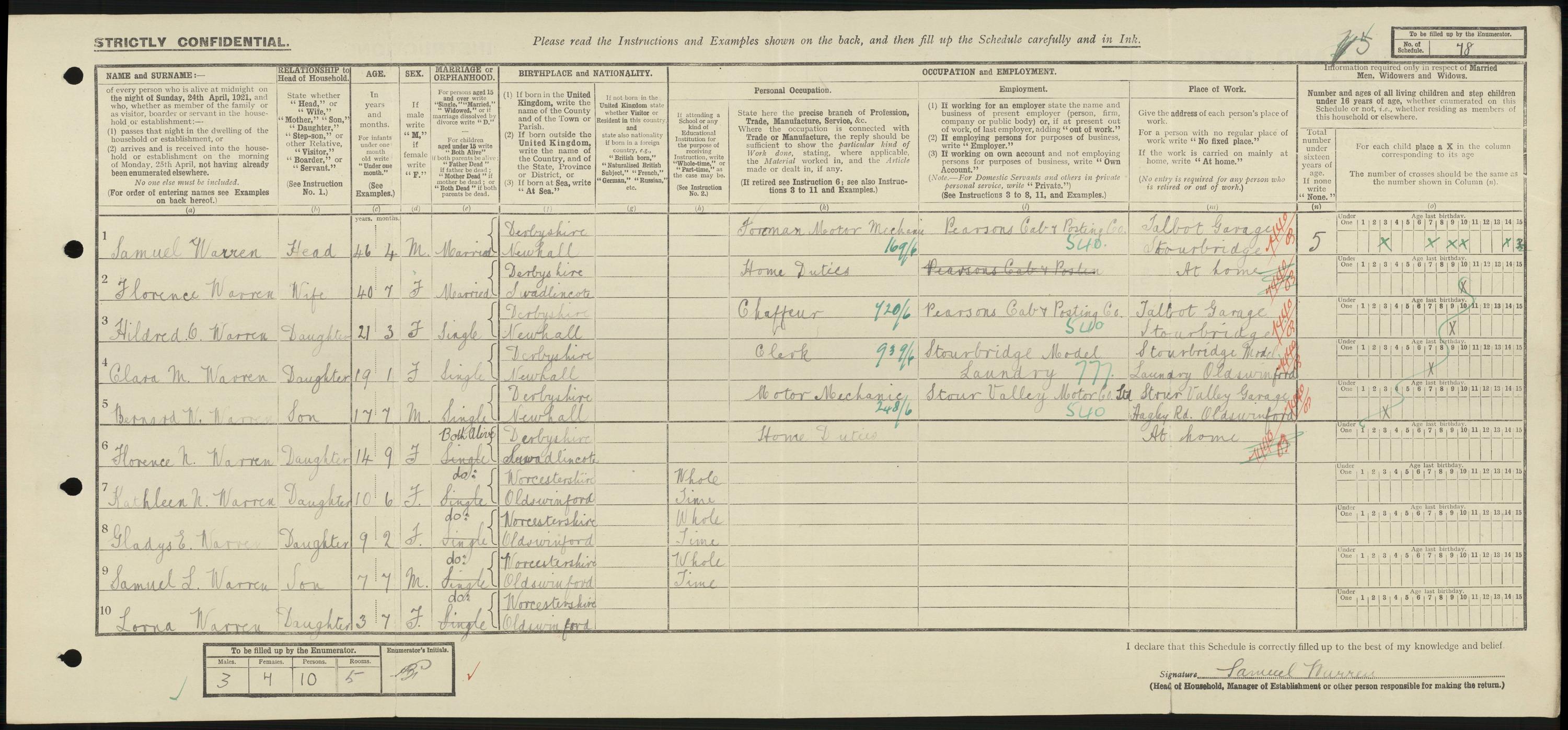

1921 census, Stourbridge:

Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor. There is a family story of Hildred being involved in a car accident involving a fatality and that she had to go to court.

Stone Manor is in a tiny village called Stone, near Kidderminster, Worcestershire. It used to be a private house, but has been a hotel and nightclub for some years. We knew in the family that Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor and that Joan was born there. Around 2007 Joan held a family party there.

Stone Manor, Stone, Worcestershire:

I asked on a Kidderminster Family Research group about Stone Manor in the 1920s:

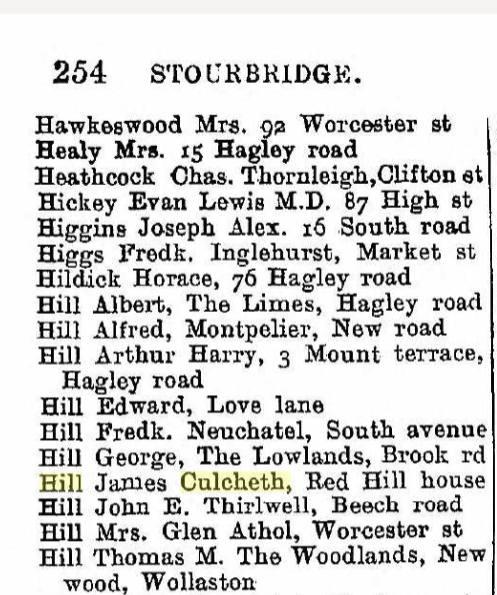

“the original Stone Manor burnt down and the current building dates from the early 1920’s and was built for James Culcheth Hill, completed in 1926”

But was there a fire at Stone Manor?

“I’m not sure there was a fire at the Stone Manor… there seems to have been a fire at another big house a short distance away and it looks like stories have crossed over… as the dates are the same…”JC Hill was one of the witnesses at Hildred and Reginalds wedding in Stone in 1924. K Warren, Hildreds sister Kay, was the other:

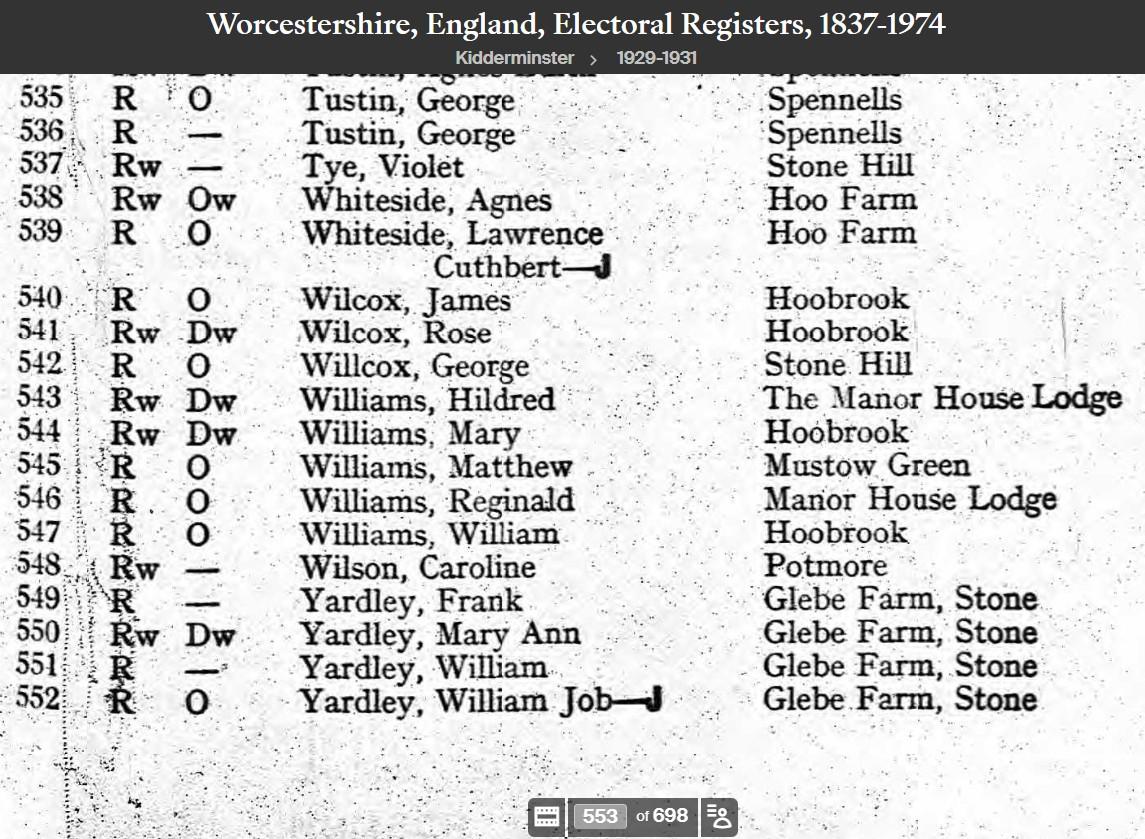

I searched the census and electoral rolls for James Culcheth Hill and found him at the Stone Manor on the 1929-1931 electoral rolls for Stone, and Hildred and Reginald living at The Manor House Lodge, Stone:

On the 1911 census James Culcheth Hill was a 12 year old student at Eastmans Royal Naval Academy, Northwood Park, Crawley, Winchester. He was born in Kidderminster in 1899. On the same census page, also a student at the school, is Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, born in 1900 in Stourbridge. The unusual middle name would seem to indicate that they might be related.

A member of the Kidderminster Family Research group kindly provided this article:

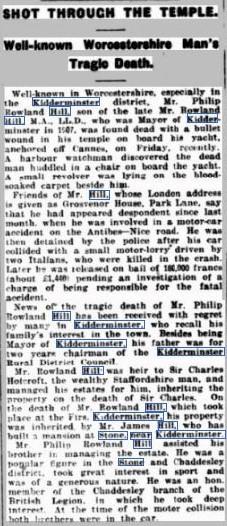

SHOT THROUGH THE TEMPLE

Well known Worcestershire man’s tragic death.

Dudley Chronicle 27 March 1930.

Well known in Worcestershire, especially the Kidderminster district, Mr Philip Rowland Hill MA LLD who was mayor of Kidderminster in 1907 was found dead with a bullet wound through his temple on board his yacht, anchored off Cannes, on Friday, recently. A harbour watchman discovered the dead man huddled in a chair on board the yacht. A small revolver was lying on the blood soaked carpet beside him.

Friends of Mr Hill, whose London address is given as Grosvenor House, Park Lane, say that he appeared despondent since last month when he was involved in a motor car accident on the Antibes ~ Nice road. He was then detained by the police after his car collided with a small motor lorry driven by two Italians, who were killed in the crash. Later he was released on bail of 180,000 francs (£1440) pending an investigation of a charge of being responsible for the fatal accident. …….

Mr Rowland Hill (Philips father) was heir to Sir Charles Holcroft, the wealthy Staffordshire man, and managed his estates for him, inheriting the property on the death of Sir Charles. On the death of Mr Rowland HIll, which took place at the Firs, Kidderminster, his property was inherited by Mr James (Culcheth) Hill who had built a mansion at Stone, near Kidderminster. Mr Philip Rowland Hill assisted his brother in managing the estate. …….

At the time of the collison both brothers were in the car.

This article doesn’t mention who was driving the car ~ could the family story of a car accident be this one? Hildred and Reg were working at Stone Manor, both were (or at least previously had been) chauffeurs, and Philip Hill was helping James Culcheth Hill manage the Stone Manor estate at the time.

This photograph was taken circa 1931 in Llanaeron, Wales. Hildred is in the middle on the back row:

Sally Gray sent the photo with this message:

“Joan gave me a short note: Photo was taken when they lived in Wales, at Llanaeron, before Janet was born, & Aunty Lorna (my mother) lived with them, to take Joan to school in Aberaeron, as they only spoke Welsh at the local school.”

Hildred and Reginalds daughter Janet was born in 1932 in Stratford. It would appear that Hildred and Reg moved to Wales just after the car accident, and shortly afterwards moved to Stratford.

In 1921 James Culcheth Hill was living at Red Hill House in Stourbridge. Although I have not been able to trace Reginald Williams yet, perhaps this Stourbridge connection with his employer explains how Hildred met Reginald.

Sir Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, the other pupil at the school in Winchester with James Culcheth Hill, was indeed related, as Sir Holcroft left his estate to James Culcheth Hill’s father. Sir Reginald was born in 1899 in Upper Swinford, Stourbridge. Hildred also lived in that part of Stourbridge in the early 1900s.

1921 Red Hill House:

The 2007 family reunion organized by Joan Williams at Stone Manor: Joan in black and white at the front.

Unrelated to the Warrens, my fathers friends (and customers at The Fox when my grandmother Peggy Edwards owned it) Geoff and Beryl Lamb later bought Stone Manor.

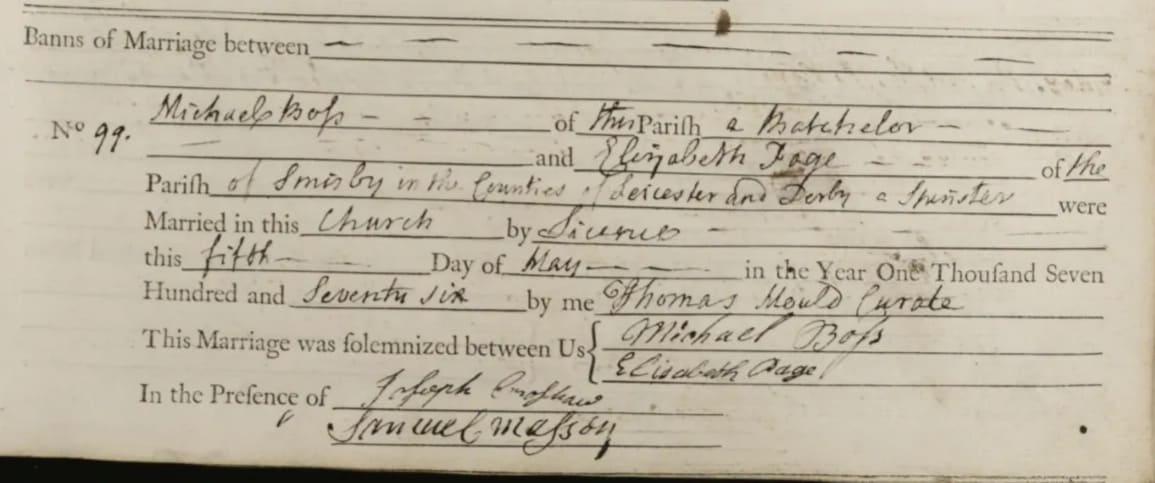

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

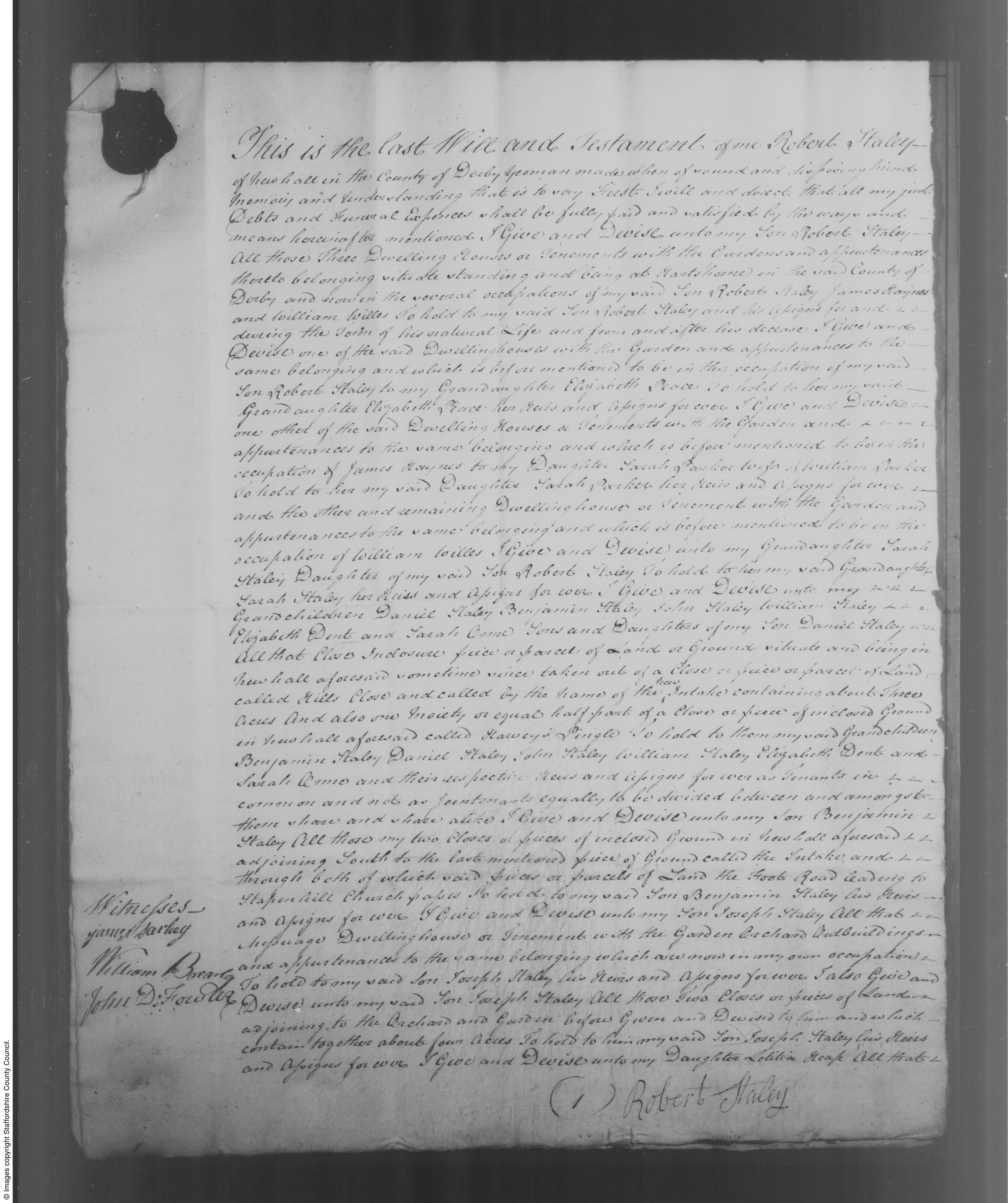

Looking for Robert Staley

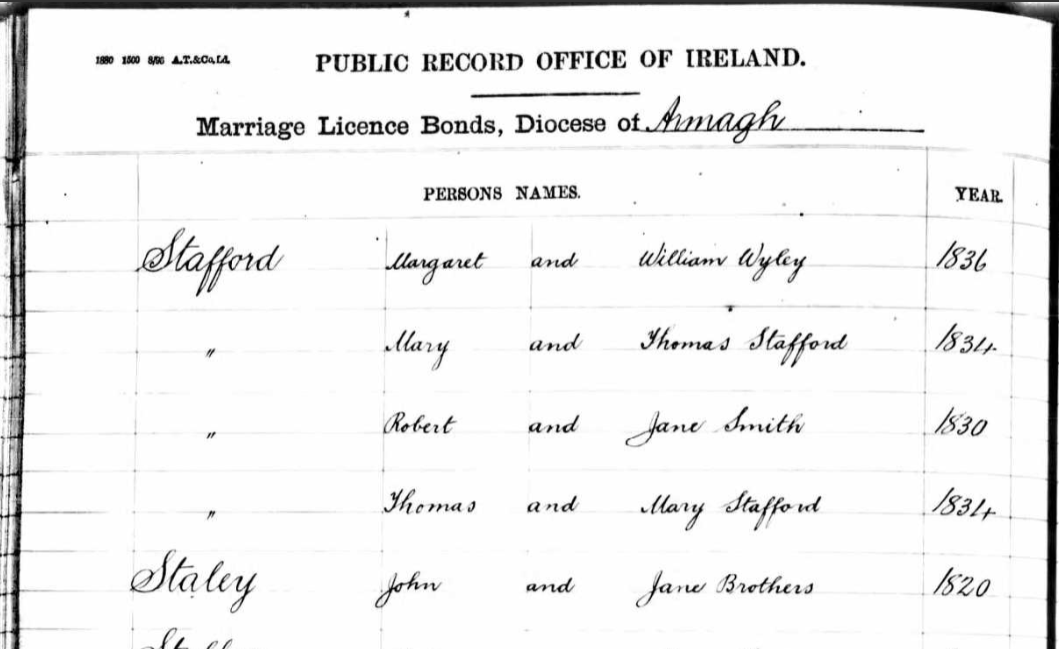

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

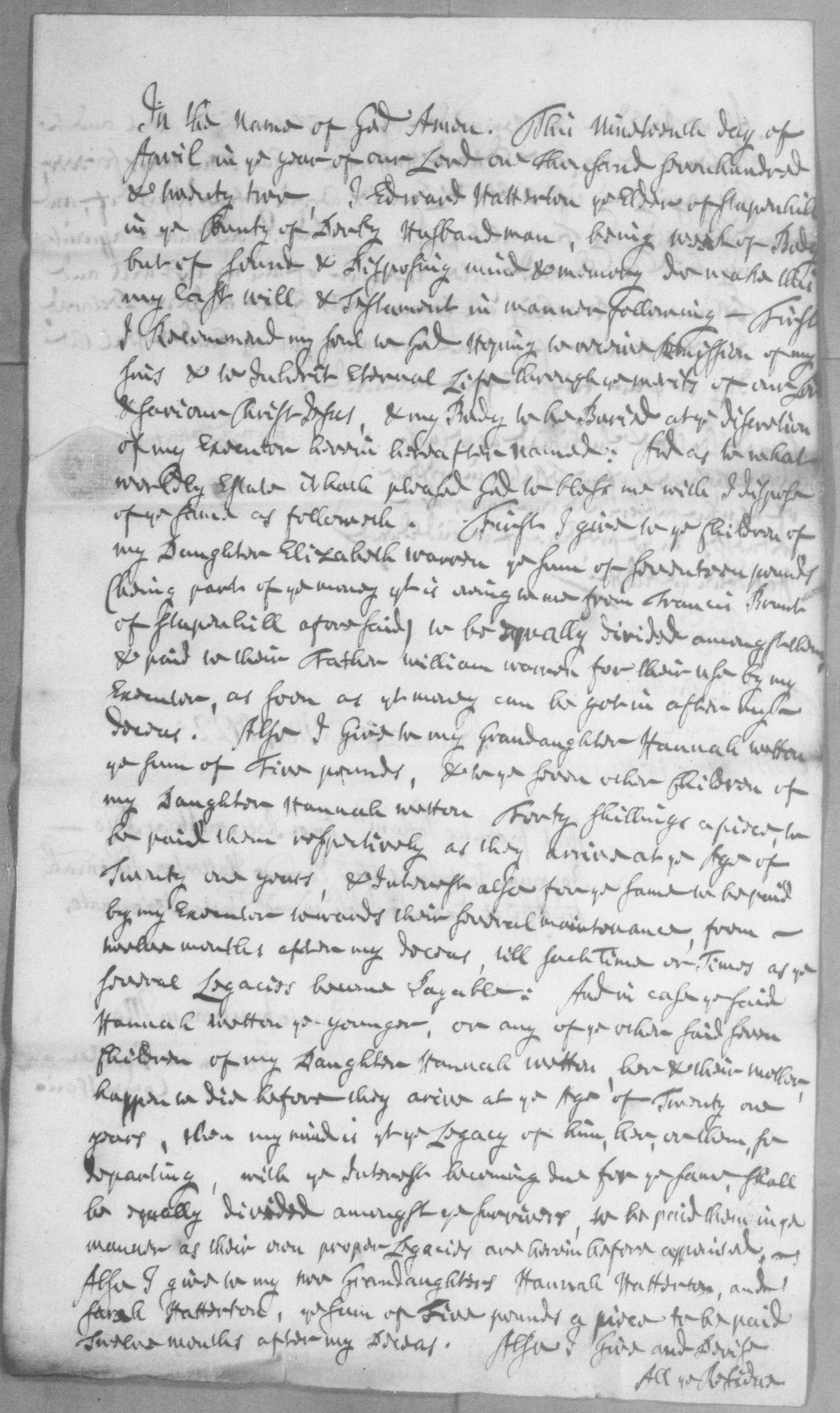

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

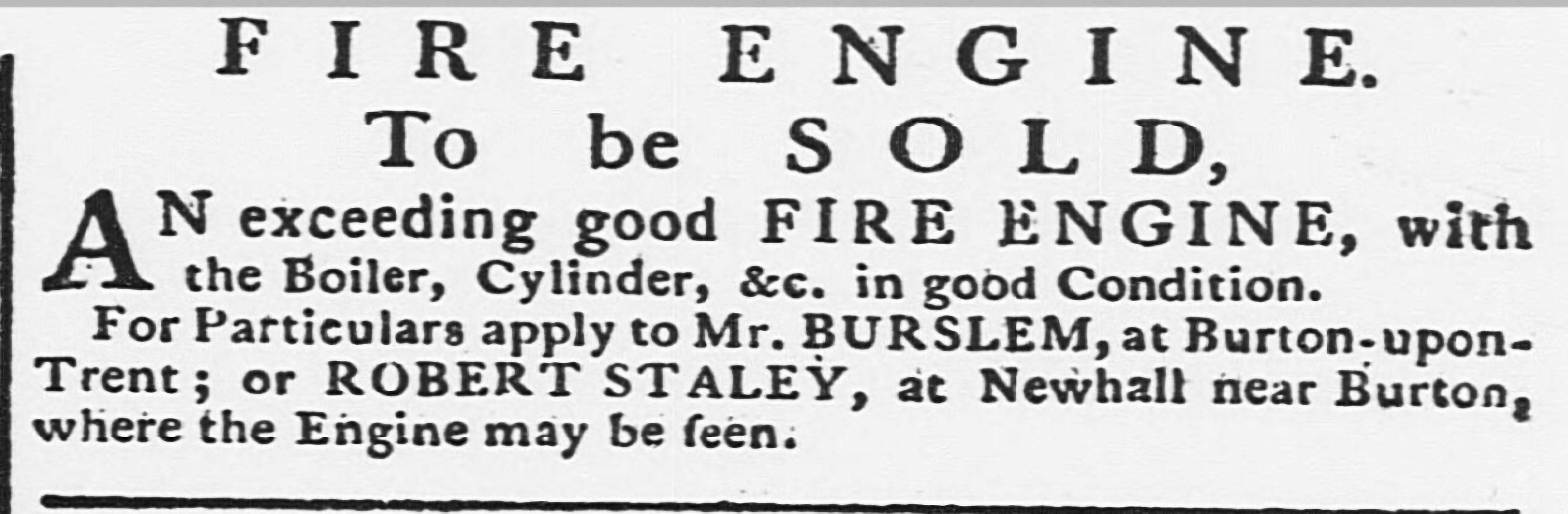

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

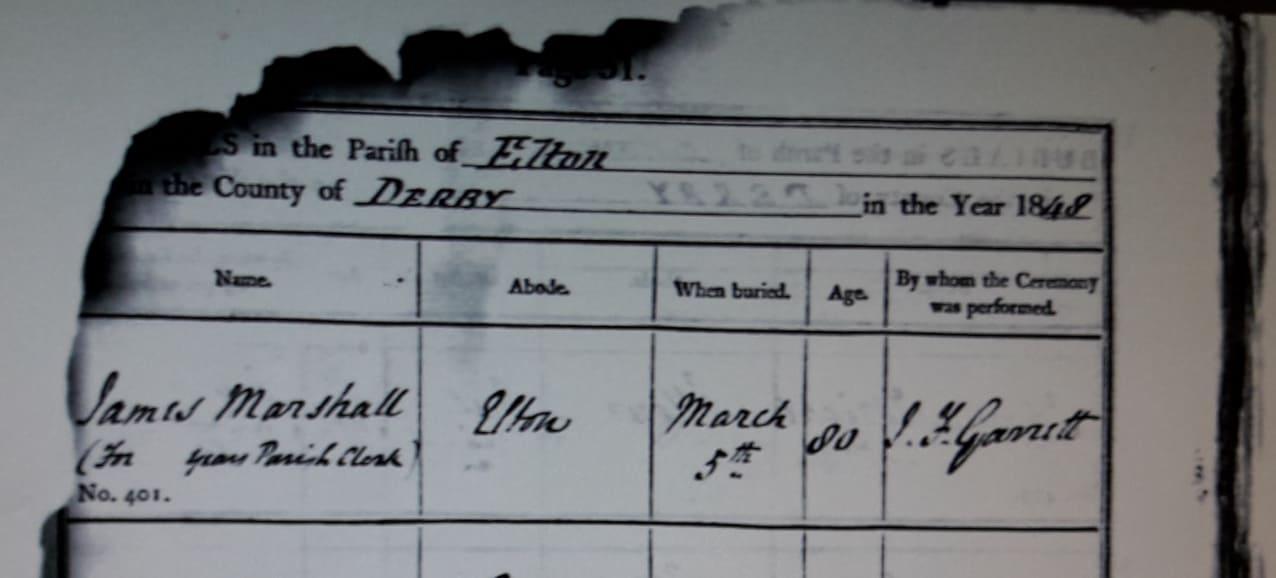

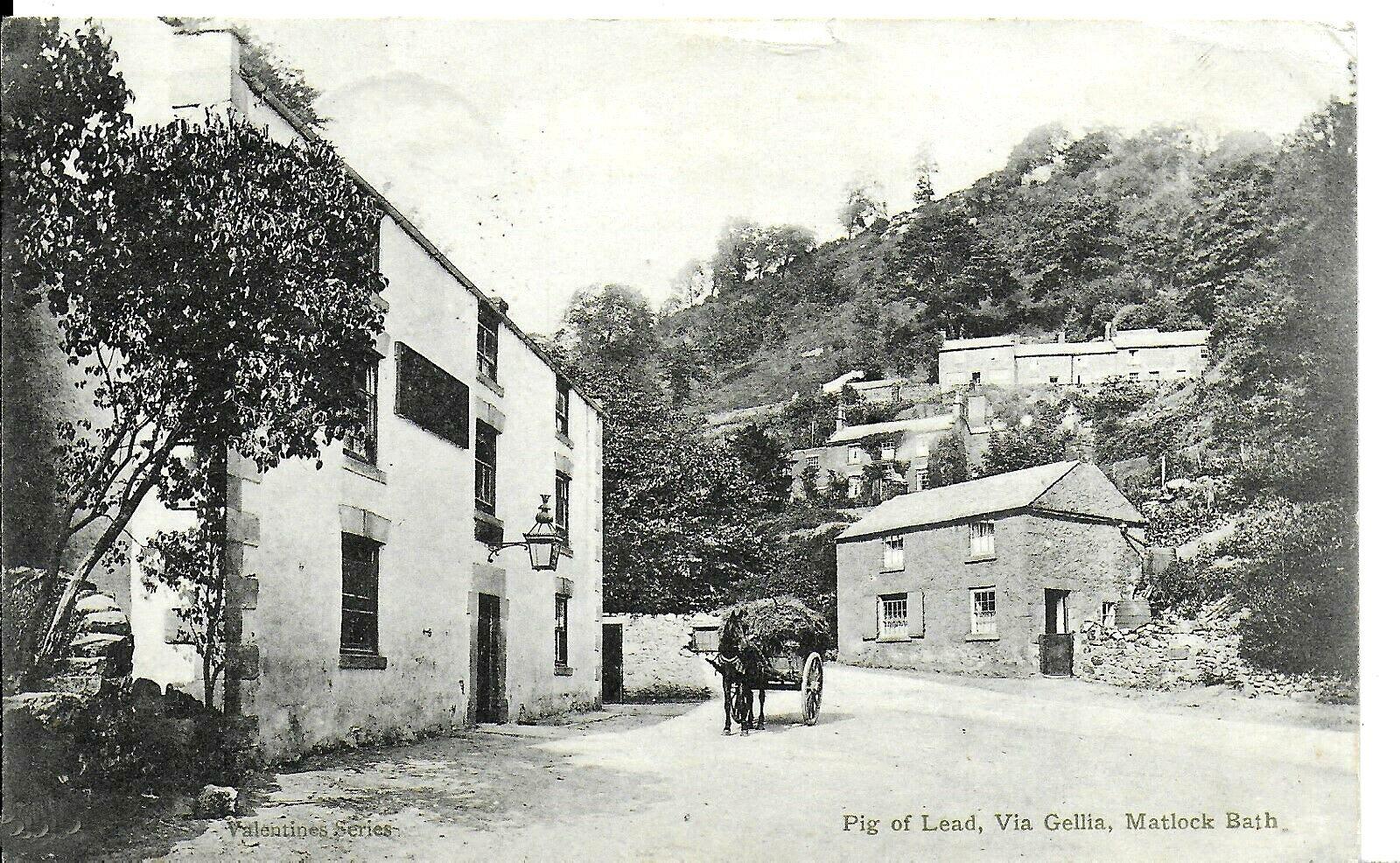

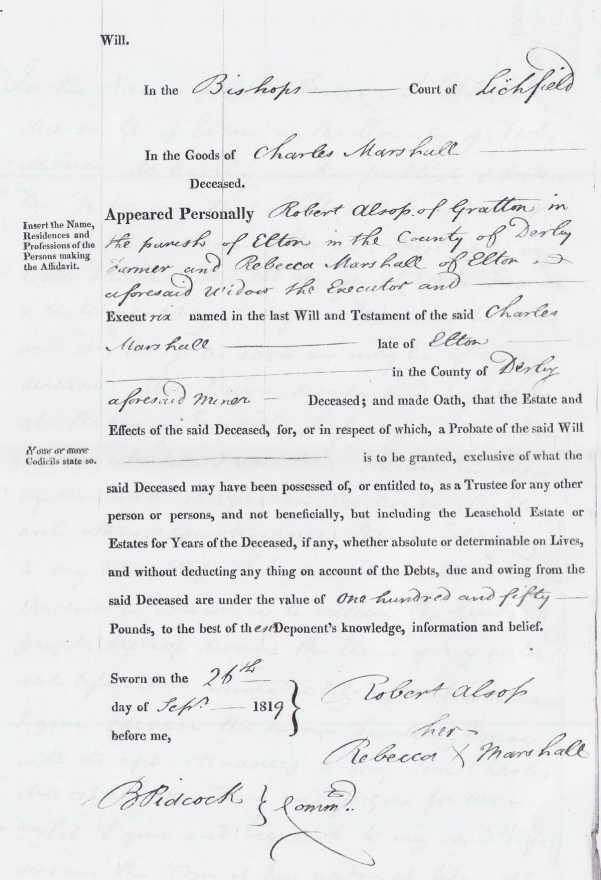

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

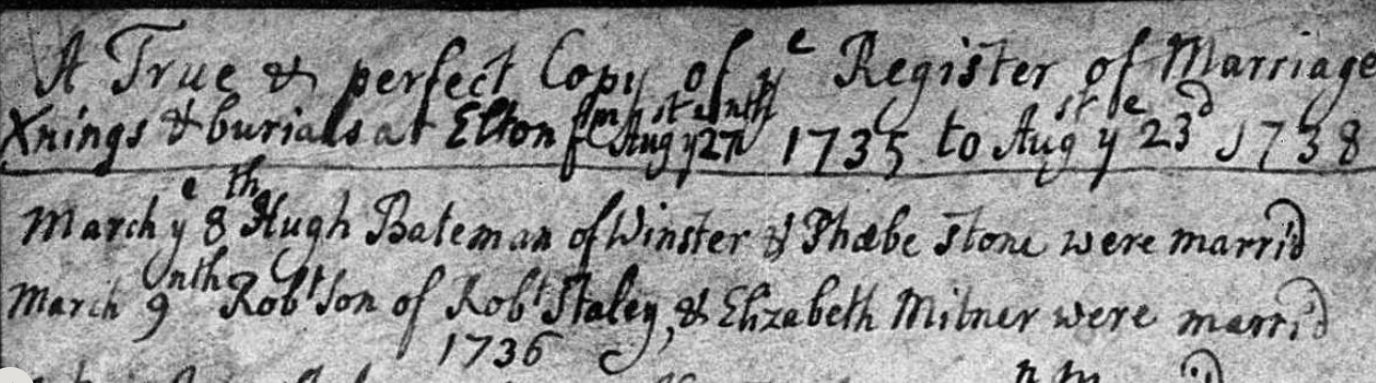

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

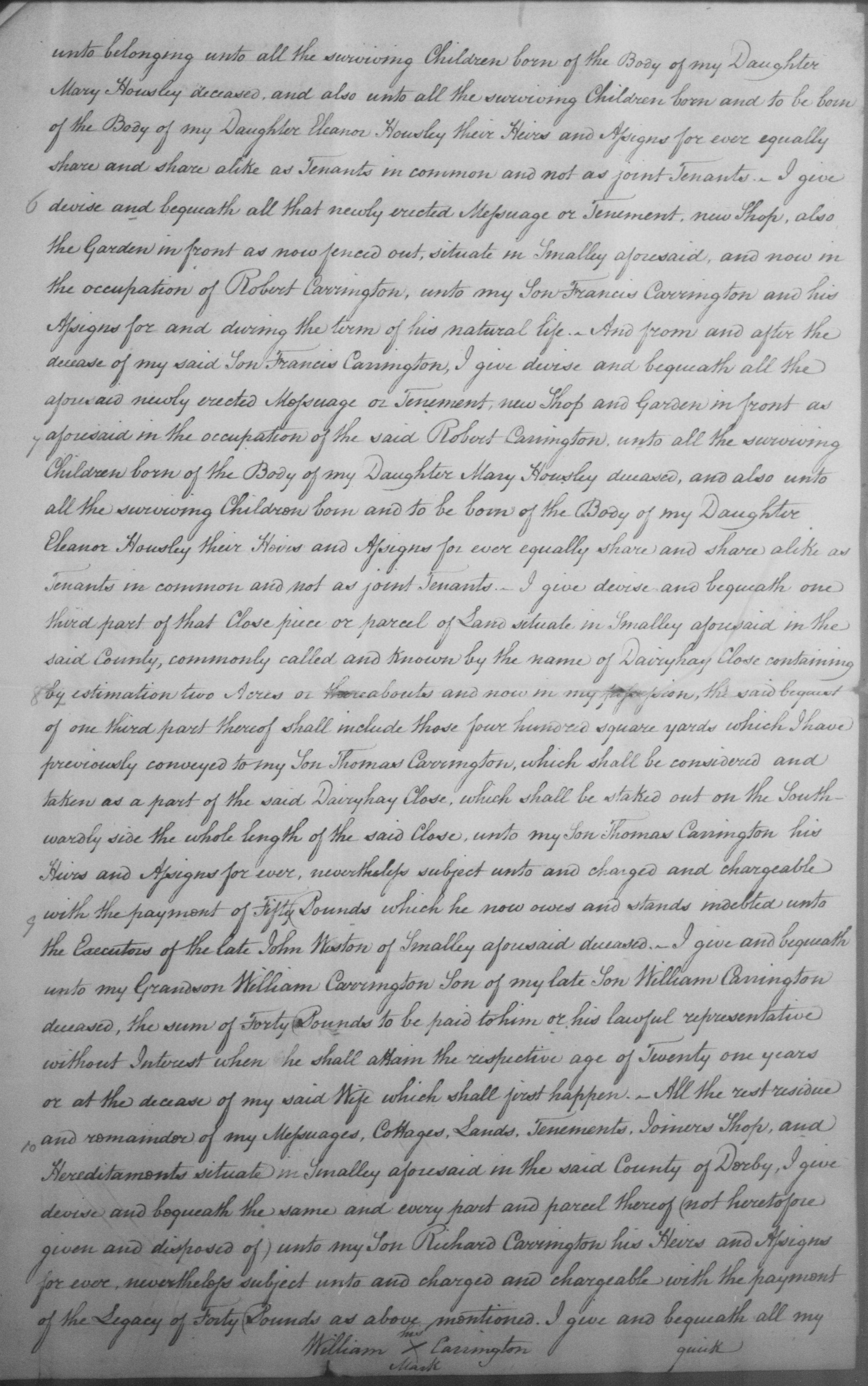

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.

I give, devise and bequeath to Humphrey Trafford Nadin of Church Gresely in the said County of Derby Esquire and John Wilkinson of Newhall aforesaid yeoman all my messuages, lands, tenements, hereditaments and real and personal estates to hold to them, their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns until Richard Moon the youngest of my reputed sons by Elizabeth Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years upon trust that they, my said trustees, (or the survivor of them, his heirs, executors, administrators or assigns), shall and do manage and carry on my farm at Newhall aforesaid and pay and apply the rents, issues and profits of all and every of my said real and personal estates in for and towards the support, maintenance and education of all my reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon until the said Richard Moon my youngest reputed son shall attain his said age of twenty one years and equally share and share and share alike.

And it is my will and desire that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall recruit and keep up the stock upon my farm as they in their discretion shall see occasion or think proper and that the same shall not be diminished. And in case any of my said reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon shall be married before my said reputed youngest son shall attain his age of twenty one years that then it is my will and desire that non of their husbands or wives shall come to my farm or be maintained there or have their abode there. That it is also my will and desire in case my reputed children or any of them shall not be steady to business but instead shall be wild and diminish the stock that then my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority in their discretion to sell and dispose of all or any part of my said personal estate and to put out the money arising from the sale thereof to interest and to pay and apply the interest thereof and also thereunto of the said real estate in for and towards the maintenance, education and support of all my said reputed children by the said

Elizabeth Moon as they my said trustees in their discretion that think proper until the said Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years.Then I give to my grandson Daniel Staley the sum of ten pounds and to each and every of my sons and daughters namely Daniel Staley, Benjamin Staley, John Staley, William Staley, Elizabeth Dent and Sarah Orme and to my niece Ann Brearly the sum of five pounds apiece.

I give to my youngest reputed son Richard Moon one share in the Ashby Canal Navigation and I direct that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority to pay and apply all or any part of the fortune or legacy hereby intended for my youngest reputed son Richard Moon in placing him out to any trade, business or profession as they in their discretion shall think proper.

And I direct that to my said sons and daughters by my late wife and my said niece shall by wholly paid by my said reputed son Richard Moon out of the fortune herby given him. And it is my will and desire that my said reputed children shall deliver into the hands of my executors all the monies that shall arise from the carrying on of my business that is not wanted to carry on the same unto my acting executor and shall keep a just and true account of all disbursements and receipts of the said business and deliver up the same to my acting executor in order that there may not be any embezzlement or defraud amongst them and from and immediately after my said reputed youngest son Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years then I give, devise and bequeath all my real estate and all the residue and remainder of my personal estate of what nature and kind whatsoever and wheresoever unto and amongst all and every my said reputed sons and daughters namely William Moon, Thomas Moon, Joseph Moon, Richard Moon, Ann Moon, Margaret Moon and to my reputed daughter Mary Brearly to hold to them and their respective heirs, executors, administrator and assigns for ever according to the nature and tenure of the same estates respectively to take the same as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.And lastly I nominate and appoint the said Humphrey Trafford Nadin and John Wilkinson executors of this my last will and testament and guardians of all my reputed children who are under age during their respective minorities hereby revoking all former and other wills by me heretofore made and declaring this only to be my last will.

In witness whereof I the said Daniel Staley the testator have to this my last will and testament set my hand and seal the eleventh day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and five.

June 6, 2022 at 12:58 pm #6303In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

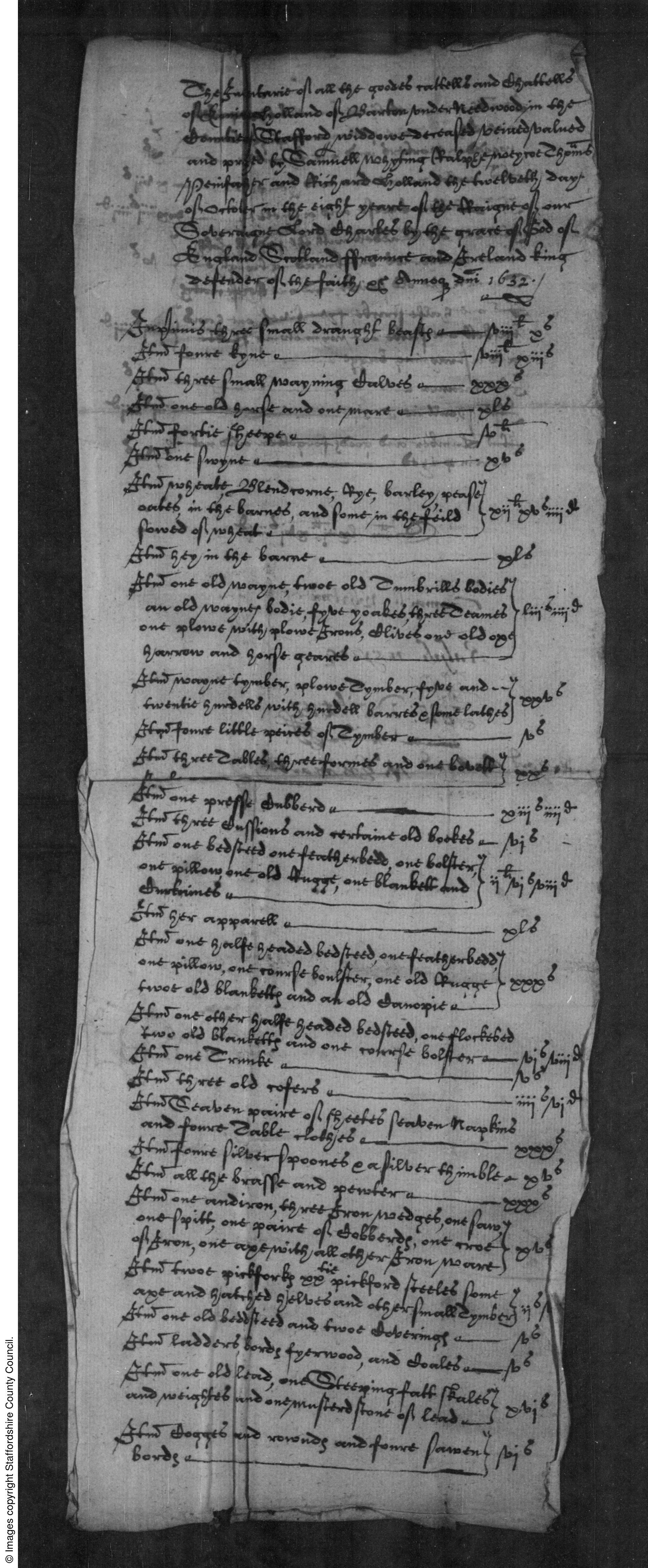

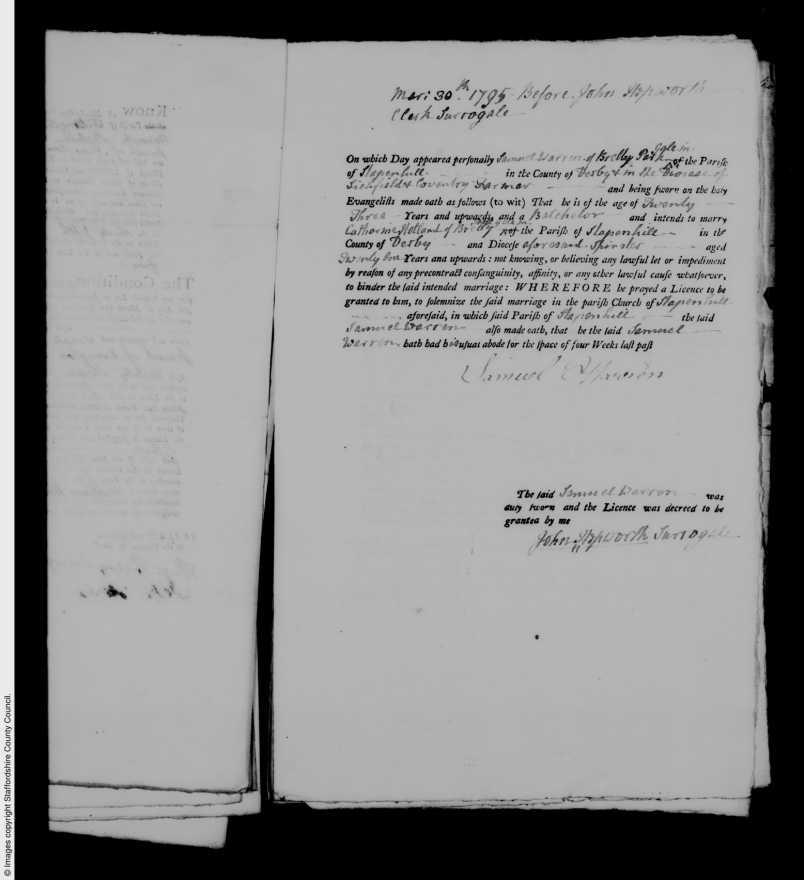

The Hollands of Barton under Needwood

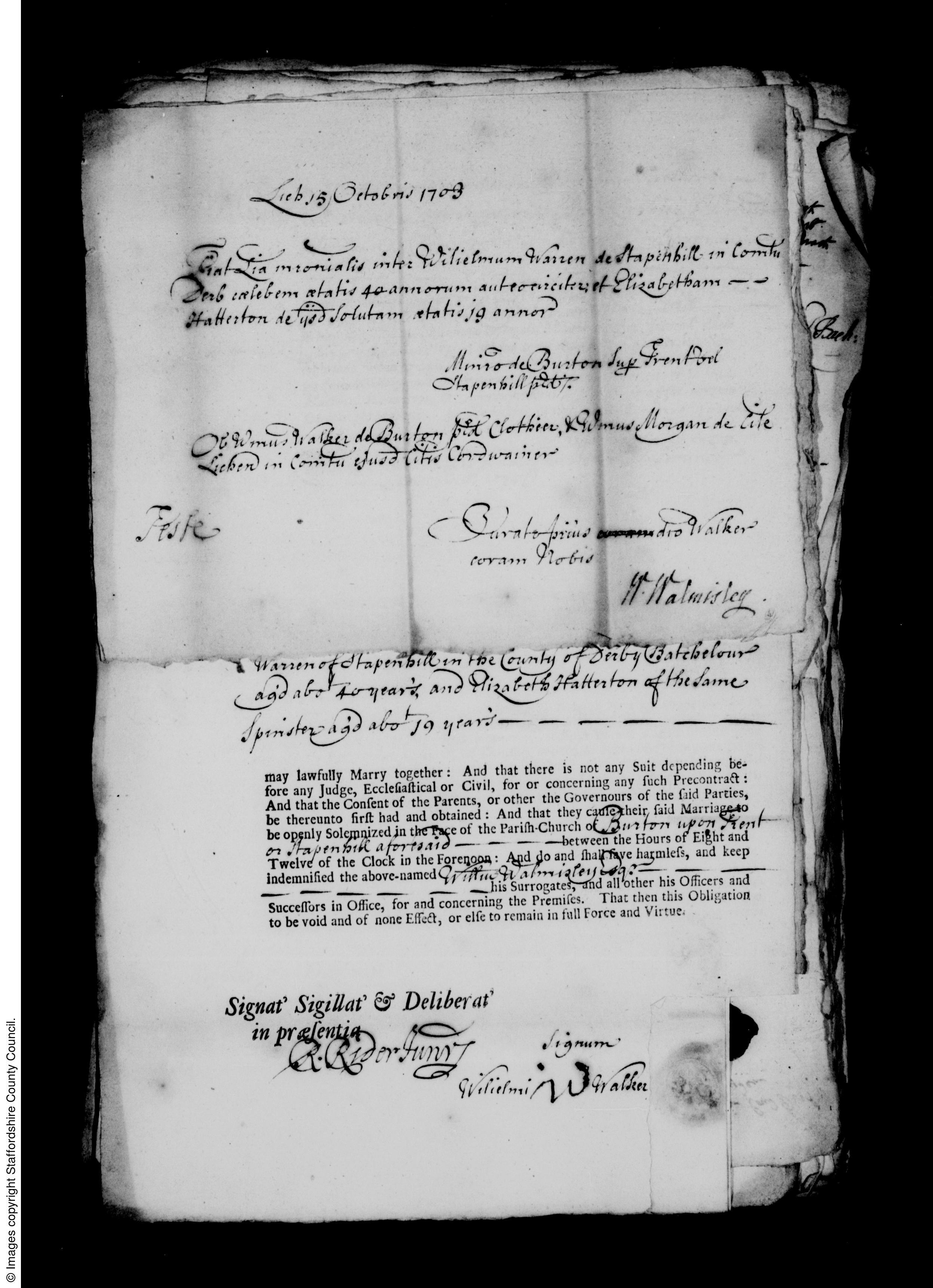

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795.

I joined a Barton under Needwood History group and found an incredible amount of information on the Holland family, but first I wanted to make absolutely sure that our Catherine Holland was one of them as there were also Hollands in Newhall. Not only that, on the marriage licence it says that Catherine Holland was from Bretby Park Gate, Stapenhill.

Then I noticed that one of the witnesses on Samuel’s brother Williams marriage to Ann Holland in 1796 was John Hair. Hannah Hair was the wife of Thomas Holland, and they were the Barton under Needwood parents of Catherine. Catherine was born in 1775, and Ann was born in 1767.

The 1851 census clinched it: Catherine Warren 74 years old, widow and formerly a farmers wife, was living in the household of her son John Warren, and her place of birth is listed as Barton under Needwood. In 1841 Catherine was a 64 year old widow, her husband Samuel having died in 1837, and she was living with her son Samuel, a farmer. The 1841 census did not list place of birth, however. Catherine died on 31 March 1861 and does not appear on the 1861 census.

Once I had established that our Catherine Holland was from Barton under Needwood, I had another look at the information available on the Barton under Needwood History group, compiled by local historian Steve Gardner.

Catherine’s parents were Thomas Holland 1737-1828 and Hannah Hair 1739-1822.

Steve Gardner had posted a long list of the dates, marriages and children of the Holland family. The earliest entries in parish registers were Thomae Holland 1562-1626 and his wife Eunica Edwardes 1565-1632. They married on 10th July 1582. They were born, married and died in Barton under Needwood. They were direct ancestors of Catherine Holland, and as such my direct ancestors too.

The known history of the Holland family in Barton under Needwood goes back to Richard De Holland. (Thanks once again to Steve Gardner of the Barton under Needwood History group for this information.)

“Richard de Holland was the first member of the Holland family to become resident in Barton under Needwood (in about 1312) having been granted lands by the Earl of Lancaster (for whom Richard served as Stud and Stock Keeper of the Peak District) The Holland family stemmed from Upholland in Lancashire and had many family connections working for the Earl of Lancaster, who was one of the biggest Barons in England. Lancaster had his own army and lived at Tutbury Castle, from where he ruled over most of the Midlands area. The Earl of Lancaster was one of the main players in the ‘Barons Rebellion’ and the ensuing Battle of Burton Bridge in 1322. Richard de Holland was very much involved in the proceedings which had so angered Englands King. Holland narrowly escaped with his life, unlike the Earl who was executed.

From the arrival of that first Holland family member, the Hollands were a mainstay family in the community, and were in Barton under Needwood for over 600 years.”Continuing with various items of information regarding the Hollands, thanks to Steve Gardner’s Barton under Needwood history pages:

“PART 6 (Final Part)

Some mentions of The Manor of Barton in the Ancient Staffordshire Rolls:

1330. A Grant was made to Herbert de Ferrars, at le Newland in the Manor of Barton.

1378. The Inquisitio bonorum – Johannis Holand — an interesting Inventory of his goods and their value and his debts.

1380. View of Frankpledge ; the Jury found that Richard Holland was feloniously murdered by his wife Joan and Thomas Graunger, who fled. The goods of the deceased were valued at iiij/. iijj. xid. ; one-third went to the dead man, one-third to his son, one- third to the Lord for the wife’s share. Compare 1 H. V. Indictments. (1413.)

That Thomas Graunger of Barton smyth and Joan the wife of Richard de Holond of Barton on the Feast of St. John the Baptist 10 H. II. (1387) had traitorously killed and murdered at night, at Barton, Richard, the husband of the said Joan. (m. 22.)

The names of various members of the Holland family appear constantly among the listed Jurors on the manorial records printed below : —

1539. Richard Holland and Richard Holland the younger are on the Muster Roll of Barton

1583. Thomas Holland and Unica his wife are living at Barton.

1663-4. Visitations. — Barton under Needword. Disclaimers. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.

1609. Richard Holland, Clerk and Alice, his wife.

1663-4. Disclaimers at the Visitation. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.”I was able to find considerably more information on the Hollands in the book “Some Records of the Holland Family (The Hollands of Barton under Needwood, Staffordshire, and the Hollands in History)” by William Richard Holland. Luckily the full text of this book can be found online.

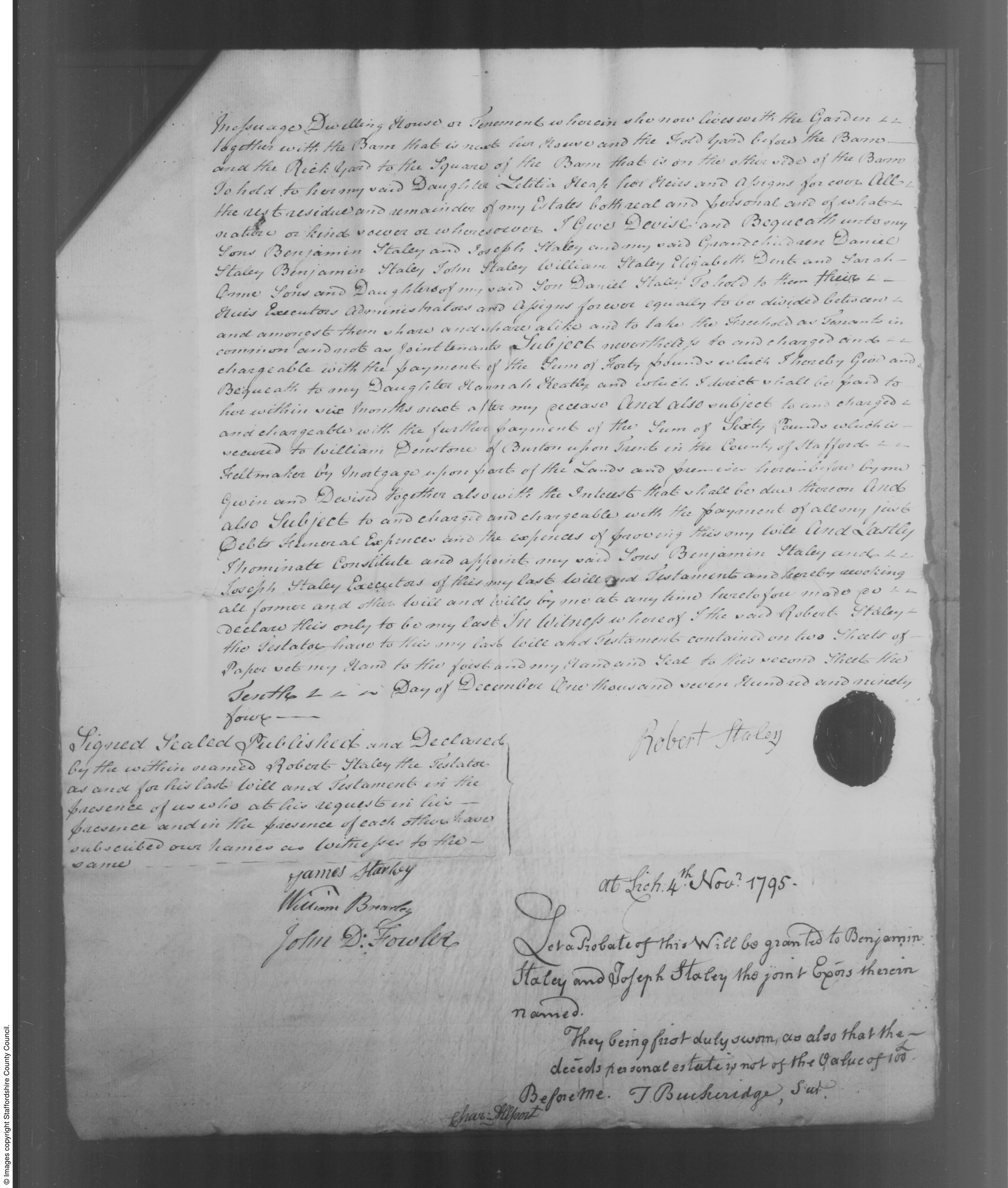

William Richard Holland (Died 1915) An early local Historian and author of the book:

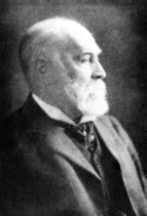

‘Holland House’ taken from the Gardens (sadly demolished in the early 60’s):

Excerpt from the book:

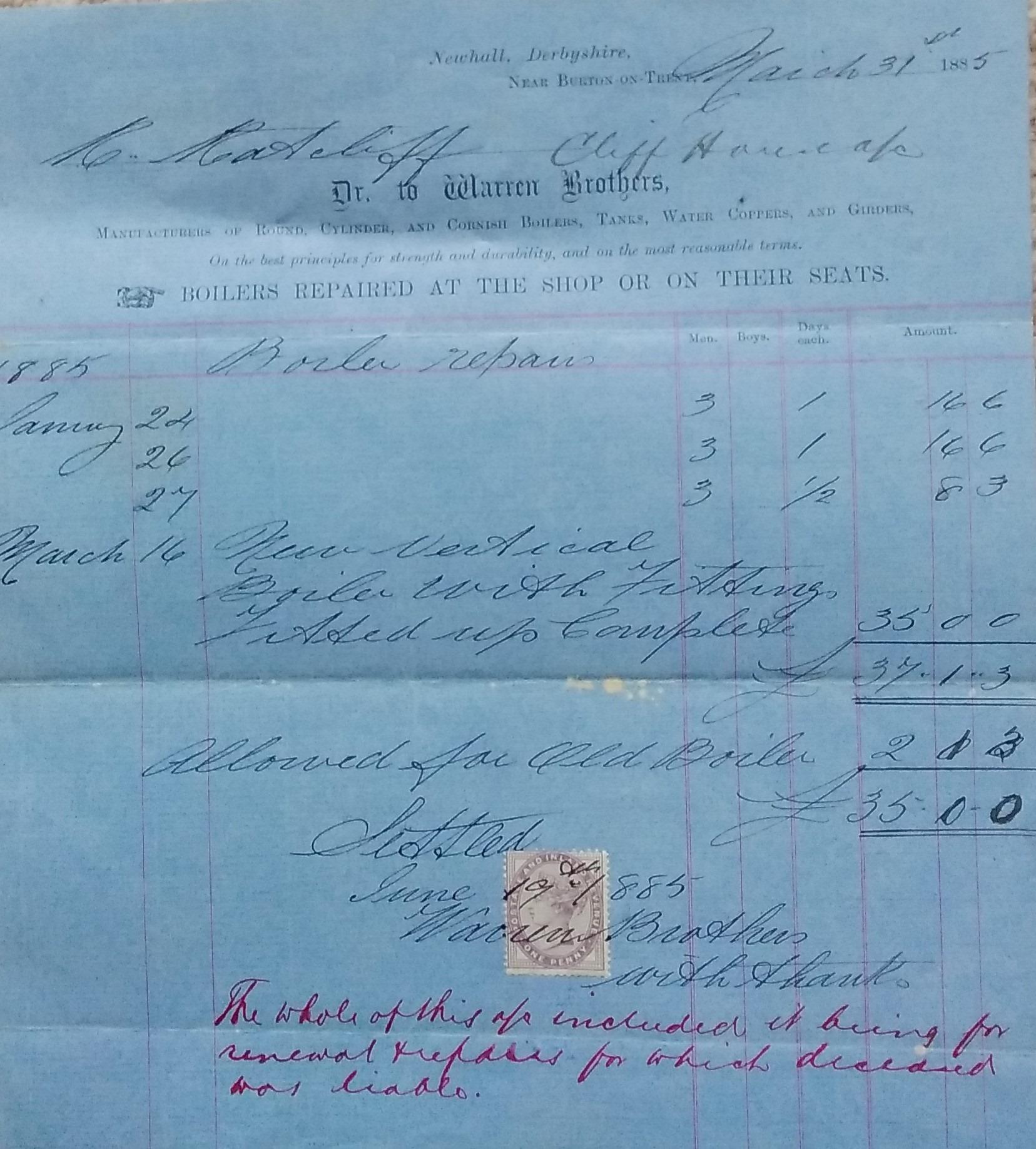

“The charter, dated 1314, granting Richard rights and privileges in Needwood Forest, reads as follows: