Search Results for 'papers'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 4, 2026 at 9:59 pm #8042

In reply to: Finder’s Keepers of the Hoard

A continuous, fast-moving FPV drone shot.

The Start: The camera zips through a sterile, white modern reception area with a sign reading ‘Sanctus Training Ltd.’ It flies over a bored receptionist’s desk and straight through a pair of unassuming double doors.

The Reveal: The moment the doors pass, the world expands impossible. We are now inside a massive, cathedral-like Grand Townhouse built of glowing golden Cotswold stone.

The Hoard: The drone dives into a ‘canyon’ of hoarded objects. It weaves perilously between towering stacks of yellowed newspapers, piles of 17th-century furniture, and a mountain of washing machines.

The Architecture: As the drone speeds up, we pass tall, elegant Georgian windows on the left (showing a blur of an overgrown orchard and stables outside). On the right, the architecture shifts to heavy, rough stone arches—the Medieval Norman wing.

The Details: The camera narrowly misses a hanging chandelier made of plastic coat hangers and crystal, zooms over a grand dining table buried in Roman pottery and taxidermy, and finally flies up towards the vaulted ceiling of a Norman Chapel, where a beam of purple stained-glass light catches dust motes dancing in the air.”

December 30, 2025 at 6:42 pm #8003In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

JOHN BROOKS ALIAS PRIESTLAND

1766-1846John Brooks, my 5x great grandfather, was born in 1766, according to the 1841 census and the burial register in 1846 which stated his age at death as 80 years, but no baptism has been found thus far.

On his first son’s baptism in 1790 the parish register states “John son of John and Elizabeth Brooks Priestnal was baptised”. The name Priestnal was not mentioned in any further sibling baptism, and he was John Brooks on his marriage, on the 1841 census and on his burial in the Netherseal parish register. The name Priestnal was a mystery.

I wondered why there was a nine year gap between the first son John, and the further six siblings, and found that his first wife Elizabeth Wilson died in 1791, and in 1798 John married Elizabeth Cowper, a widow.

John was a farmer of Netherseal on both marriage licences, and of independent means on the 1841 census.

Without finding a baptism it was impossible to go further back, and I was curious to find another tree on the ancestry website with many specific dates but no sources attached, that had Thomas Brooks as his father and his mother as Mary Priestland. I couldn’t find a marriage for John and Mary Priestland, so I sent a message to the owner of the tree, and before receiving a reply, did a bit more searching.

I found an article in the newspaper archives dated 9 August 1839 about a dispute over a right of way, and John Brooks, 73 years of age and a witness for the complainant, said that he had lived in Netherseal all his life (and had always know that public right of way and so on).

I found three lists of documents held by the Derby Records Office about property deeds and transfers, naming a John Brooks alias Priestland, one in 1794, one in 1814, and one in 1824. One of them stated that his father was Thomas Brooks. I was beginning to wonder if Thomas Brooks and Mary Priestland had never married, and this proved to be the case.

The Australian owner of the other tree replied, and said that they had paid a researcher in England many years ago, and that she would look through a box of papers. She sent me a transcribed summary of the main ponts of Thomas Brooks 1784 will:

Thomas Brooks, husbandman of Netherseal

To daughter Ann husband of George Oakden, £20.

To grandson William Brooks, £20.

To son William Brooks and his wife Ann, one shilling each.

To his servant Mary Priestland, £20 and certain household effects and certain property.

To his natural son John Priestland alias Brooks, various properties and the residue of his estate.

John Priestland alias Brooks appointed sole executor.It would appear that Thomas Brooks left the bulk of his estate to his illegitimate son, and more to his servant Mary Priestland than to his legitimate children.

THOMAS BROOKS

1706-1784

Thomas Brooks, my 6x great grandfather, had three wives. He had four children with his first wife, Elizabeth, between 1732 and 1737. Elizabeth died in 1737. He then married Mary Bath, who died in 1763. Thomas had no children with Mary Bath. In 1765 Thomas married Mary Beck. In 1766 his son John Brooks alias Priestland was born to his servant Mary Priestland.

Thomas Brooks parents were John Brooks 1671-1741, and his wife Anne Speare 1674-1718, both of Netherseal, Leicestershire.

December 30, 2025 at 1:13 pm #8001In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

John Brooks

The Father of Catherine Housley’s Mother, Elizabeth Brooks.I had not managed to find out anything about the Brooks family in previous searches. We knew that Elizabeth Brooks father was J Brooks, cooper, from her marriage record. A cooper is a man who makes barrels.

Elizabeth was born in 1819 in Sutton Coldfield, parents John and Mary Brooks. Elizabeth had three brothers, all baptised in Sutton Coldfield: Thomas 1815-1821, John 1816-1821, and William Brooks, 1822-1875. William was known to Samuel Housley, the husband of Elizabeth, which we know from the Housley Letters, sent from the family in Smalley to George, Samuel’s brother, in USA, from the 1850s to 1870s. More to follow on William Brooks.

Elizabeth married Samuel Housley in Wolverhampton in 1844. Elizabeth and Samuel had three daughters in Smalley before Elizabeth’s death from TB in 1849, the youngest, just 6 weeks old at the time, was my great great grandmother Catherine Housley.

Elizabeth’s mother Mary died in 1823, and it not known if Elizabeth, then four, and William, a year old, stayed at home with their father or went to stay with relatives. There were no census records during those years.

John Brooks married Mary Wagstaff in 1814 in Birmingham. A witness at their marriage was Elizabeth Brooks, and this was probably John’s sister.

On the 1841 census (which was the first census in England) John Brooks, cooper, was living on Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, with wife Sarah. I was unable to find a marriage for them before a marriage in 1845 between John Brooks and Sarah Hughes, so presumably they lived together as man and wife before they married.

Then came the lucky find with John Brooks place of birth: Netherseal, Leicestershire. The place of birth on the 1841 census wasn’t specified, thereafter it was. On the 1851 census John Brooks, cooper, and Sarah his wife were living at Queens Cross, Dudley, with a three year old granddaughter E Brooks. John was born in 1791 in Netherseal.

It was commonplace for people to move to the industrial midlands around this time, from the surrounding countryside. However if they died before the 1851 census stating place of birth, it’s usually impossible to find out where they came from, particularly if they had a common name.

John Brooks doesn’t appear on any further census. I found seven deaths registered in Dudley for a John Brooks between 1851 and 1861, so presumably he is one of them.NETHERSEAL

On 27 June 1790 appears in the Netherseal parish register “John Brooks the son of John and Elizabeth Brooks Priestnal was baptised.” The name Priestnal does not appear in the transcription, nor the Bishops Transcripts, nor on any other sibling baptism. The Priestnal mystery will be solved in the next chapter.

John Brooks senior married Elizabeth Wilson by marriage licence on 20 November 1788 in Gresley, a neighbouring town in Derbyshire (incidentally near to Swadlincote and the ancestral lines of the Warren family, which also has branches in Netherseal. The Brooks family is the Marshall side). John Brooks was a farmer.

I haven’t found a baptism yet for John Brooks senior, but his death in Netherseal in 1846 provided the age at death, eighty years old, which puts his birth at 1766. The 1841 census has his birth as 1766 as well.

In 1841 John Brooks was 75, and “independent”, meaning that he was living on his own means. The name Brooks was transcribed as Broster, making this difficult to find, but it is clearly Brooks if you look at the original.

His wife Elizabeth, born in 1762, is also on the census, as well as the Jackson family: Joseph Jackon born 1804, Elizabeth Jackson his wife born 1799, and children Joseph, born 1833, William 1834, Thomas 1835, Stephen 1836, and Mary born 1838.

John and Elizabeths daughter Elizabeth Brooks, born in 1799, married Joseph Jackson, the son of an “opulent farmer” (newspaper archives) of Tatenhill, Staffordshire. They married on the 19th January 1832 in Burton on Trent. (Elizabeth Brooks was probably the witness on John Brooks junior’s marriage to Mary Wagstaff in Birmingham in 1814, although it could have been his mother, also Elizabeth Brooks.)

(Elizabeth Jackson nee Brooks was the aunt of Elizabeth in the portrait)

Joseph Jackson was declared bankrupt in 1833 (newspapers) and in 1834 a noticed in the newspapers “to the creditors of Joseph Jackson junior”, a victualler and farmer late of Netherseal, “following no business, who was lately dischared from his Majesty’s Gaol at Stafford” whose real estate was to be sold by auction. I haven’t yet found what he was in prison for.

In 1841 Joseph appeared again in the newspapers, in which he publicly stated that he had accused Thomas Webb, surgeon of Barton Under Needwood, of owing him money “just to annoy him” and “with a view to extort money from him”. and that he undertakes to pay Thomas Webb or his attorney, the costs within 14 days.

Joseph and Elizabeth had twins in 1841, born in Netherseal, John and Ruth. Elizabeth died in 1850.

Thereafter, Joseph was a labourer at the iron works in Wednesbury, and many generations of Jacksons continued working in the iron industry in Wednesbury ~ all orignially descended from farmers in Netherseal and Tatenhill.March 23, 2025 at 7:37 am #7878In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Liz threw another pen into the tin wastepaper basket with a clatter and called loudly for Finnley while giving her writing hand a shake to relieve the cramp.

Finnley appeared sporting her habitual scowl clearly visible above her paper mask. “I hope this is important because this red dust is going to take days to clean up as it is without you keep interrupting me.”

“Oh is that what you’ve been doing, I wondered where you were. Well, let’s thank our lucky stars THAT’S all over!”

“Might be over for you,” muttered Finnley, “But that hare brained scheme of Godfrey’s has caused a very great deal of work for me. He’s made more of a mess this time than even you could have, red dust everywhere and all these obsolete parts all over the place. Roberto’s on his sixth trip to the recycling depot, and he’s barely scratched the surface.”

“Good old Roberto, at least he doesn’t keep complaining. You should take a leaf out of his book, Finnley, you’d get more work done. And speaking of books, I need another packet of pens. I’m writing my books with a pen in future. On paper. Oh and get me another pack of paper.”

Mildly curious, despite her irritation, Finnely asked her why she was writing with a pen on paper. “Is it some sort of historical re enactment? Would you prefer parchment and a quill? Or perhaps a slab of clay and some etching tools? Shall we find you a nice cave,” Finnley was warming to the theme, “And some red ochre and charcoal?”

“It may come to that,” Liz replied grimly. “But some pens and paper will do for now. Godfrey can’t interfere in my stories if I write them on paper. Robots writing my stories, honestly, who would ever have believed such a thing was possible back when I started writing all my best sellers! How times have changed!”

“Yet some things never change, ” Finnley said darkly, running her duster across the parts of Liz’s desk that weren’t covered with stacks of blue scrawled papers.

“Thank you for asking,” Liz said sarcastically, as Finnley hadn’t asked, “It’s a story about six spinsters in the early 19th century.”

“Sounds gripping,” muttered Finnley.

“And a blind uncle who never married and lived to 102. He was so good at being blind that he knew all his sheep individually.”

“Perhaps that’s why he never needed to marry,” Finnley said with a lewd titter.

“The steamy scenes I had in mind won’t be in the sheep dip,” Liz replied, “Honestly, what a low degraded mind you must have.”

“Yeah, from proof reading your trashy novels,” Finnley replied as she flounced out in search of pens and paper.

February 16, 2025 at 2:59 pm #7816In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Liz had, in her esteemed opinion, finally cracked the next great literary masterpiece.

It had everything—forbidden romance, ancient mysteries, a dash of gratuitous betrayal, and a protagonist with just the right amount of brooding introspection to make him irresistible to at least two stunningly beautiful, completely unnecessary love interests.

And, of course, there was a ghost. She would have preferred a mummy but it had been edited out one morning she woke up drooling on her work with little recollection of the night.

Unfortunately, none of this mattered because Godfrey, her ever-exasperated editor, was staring at her manuscript with the same enthusiasm he reserved for peanut shells stuck in his teeth.

“This—” he hesitated, massaging his temples, “—this is supposed to be about the Crusades.”

Liz beamed. “It is! Historical and spicy. I expect an award.”

Godfrey set down the pages and reached for his ever-dwindling bowl of peanuts. “Liz, for the love of all that is holy, why is the Templar knight taking off his armor every other page?”

Liz gasped in indignation. “You wouldn’t understand, Godfrey. It’s symbolic. A shedding of the past! A rebirth of the soul!” She made an exaggerated sweeping motion, nearly knocking over her champagne flute.

“Symbolic,” Godfrey repeated flatly, chewing another peanut. “He’s shirtless on page three, in a monastery.”

Finnley, who had been dusting aggressively, made a sharp sniff. “Disgraceful.”

Liz ignored her. “Oh please, Godfrey. You have no vision. Readers love a little intimacy in their historical fiction.”

“The priest,” Godfrey said, voice rising, “is supposed to be celibate. You explicitly wrote that his vow was unbreakable.”

Liz waved a dismissive hand. “Oh, I solved that. He forgets about it momentarily.”

Godfrey choked on a peanut. Finnley paused mid-dust, staring at Liz in horror.

Roberto, who had been watering the hydrangeas outside the window, suddenly leaned in. “Did I hear something about a forgetful priest?”

“Not now, Roberto,” Liz said sharply.

Finnley folded her arms. “And how, pray tell, does one simply forget their sacred vows?”

Liz huffed. “The same way one forgets to clean behind the grandfather clock, I imagine.”

Finnley turned an alarming shade of purple.

Godfrey was still in disbelief. “And you’re telling me,” he said, flipping through the pages in growing horror, “that this man, Brother Edric, the holy warrior, somehow manages to fall in love with—who is this—” he squinted, “—Laetitia von Somethingorother?”

Liz beamed. “Ah, yes. Laetitia! Mysterious, tragic, effortlessly seductive—”

“She’s literally the most obvious spy I’ve ever read,” Godfrey groaned, rubbing his face.

“She is not! She is enigmatic.”

“She has a knife hidden in every scene.”

“A woman should be prepared.”

Godfrey took a deep breath and picked up another sheet. “Oh fantastic. There’s a secret baby now.”

Liz nodded sagely. “Yes. I felt that revelation.”

Finnley snorted. “Roberto also felt something last week, and it turned out to be food poisoning.”

Roberto, still hovering at the window, nodded solemnly. “It was quite moving.”

Godfrey set the papers down in defeat. “Liz. Please. I’m begging you. Just one novel—just one—where the historical accuracy lasts at least until page ten.”

Liz tapped her chin. “You might have a point.”

Godfrey perked up.

Liz snapped her fingers. “I should move the shirtless scene to page two.”

Godfrey’s head hit the table.

Roberto clapped enthusiastically. “Genius! I shall fetch celebratory figs!”

Finnley sighed dramatically, threw down her duster, and walked out of the room muttering about professional disgrace.

Liz grinned, completely unfazed. “You know, Godfrey, I really don’t think you appreciate my artistic sacrifices.”

Godfrey, face still buried in his arms, groaned, “Liz, I think Brother Edric’s celibacy lasted longer than my patience.”

Liz threw a hand to her forehead theatrically. “Then it was simply not meant to be.”

Roberto reappeared, beaming. “I found the figs.”

Godfrey reached for another peanut.

He was going to need a lot more of them.

January 12, 2025 at 11:51 am #7711

January 12, 2025 at 11:51 am #7711In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — December 2022

Juliette leaned in, her phone screen glowing faintly between them. “Come on, pick something. It’s supposed to know everything—or at least sound like it does.”

Juliette was the one who’d introduced him to the app the whole world was abuzz talking about. MeowGPT.

At the New Year’s eve family dinner at Juliette’s parents, the whole house was alive with her sisters, nephews, and cousins. She entered a discussion with one of the kids, and they all seemed to know well about it. It was fun to see the adults were oblivious, himself included. He liked it about Juliette that she had such insatiable curiosity.

“It’s a life-changer, you know” she’d said “There’ll be a time, we won’t know about how we did without it. The kids born now will not know a world without it. Look, I’m sure my nephews are already cheating at their exams with it, or finding new ways to learn…”

“New ways to learn, that sounds like a mirage…. Bit of a drastic view to think we won’t live without; I’d like to think like with the mobile phones, we can still choose to live without.”

“And lose your way all the time with worn-out paper maps instead of GPS? That’s a grandpa mindset darling! I can see quite a few reasons not to choose!” she laughed.

“Anyway, we’ll see. What would you like to know about? A crazy recipe to grow hair? A fancy trip to a little known place? Write a technical instruction in the style of Elizabeth Tattler?”“Let me see…”

Matteo smirked, swirling the last sip of crémant in his glass. The lively discussions of Juliette’s family around them made the moment feel oddly private. “Alright, let’s try something practical. How about early signs of Alzheimer’s? You know, for Ma.”

Juliette’s smile softened as she tapped the query into the app. Matteo watched, half curious, half detached.

The app processed for a moment before responding in its overly chipper tone:

“Early signs of Alzheimer’s can include memory loss, difficulty planning or solving problems, and confusion with time or place. For personalized insights, understanding specific triggers, like stress or diet, can help manage early symptoms.”Matteo frowned. “That’s… general. I thought it was supposed to be revolutionary?”

“Wait for it,” Juliette said, tapping again, her tone teasing. “What if we ask it about long-term memory triggers? Something for nostalgia. Your Ma’s been into her old photos, right?”

The app spun its virtual gears and spat out a more detailed suggestion.

“Consider discussing familiar stories, music, or scents. Interestingly, recent studies on Alzheimer’s patients show a strong response to tactile memories. For example, one groundbreaking case involved genetic ancestry research coupled with personalized sensory cues.Juliette tilted her head, reading the screen aloud. “Huh, look at this—Dr. Elara V., a retired physicist, designed a patented method combining ancestral genetic research with soundwaves sensory stimuli to enhance attention and preserve memory function. Her work has been cited in connection with several studies on Alzheimer’s.”

“Elara?” Matteo’s brow furrowed. “Uncommon name… Where have I heard it before?”

Juliette shrugged. “Says here she retired to Tuscany after the pandemic. Fancy that.” She tapped the screen again, scrolling. “Apparently, she was a physicist with some quirky ideas. Had a side hustle on patents, one of which actually turned out useful. Something about genetic resonance? Sounds like a sci-fi movie.”

Matteo stared at the screen, a strange feeling tugging at him. “Genetic resonance…? It’s like these apps read your mind, huh? Do they just make this stuff up?”

Juliette laughed, nudging him. “Maybe! The system is far from foolproof, it may just have blurted out a completely imagined story, although it’s probably got it from somewhere on the internet. You better do your fact-checking. This woman would have published papers back when we were kids, and now the AI’s connecting dots.”

The name lingered with him, though. Elara. It felt distant yet oddly familiar, like the shadow of a memory just out of reach.

“You think she’s got more work like that?” he asked, more to himself than to Juliette.

Juliette handed him the phone. “You’re the one with the questions. Go ahead.”

Matteo hesitated before typing, almost without thinking: Elara Tuscany memory research.

The app processed again, and the next response was less clinical, more anecdotal.

“Elara V., known for her unconventional methods, retired to Tuscany where she invested in rural revitalization. A small village farmhouse became her retreat, and she occasionally supported artistic projects. Her most cited breakthrough involved pairing sensory stimuli with genetic lineage insights to enhance memory preservation.”Matteo tilted the phone towards Juliette. “She supports artists? Sounds like a soft spot for the dreamers.”

“Maybe she’s your type,” Juliette teased, grinning.

Matteo laughed, shaking his head. “Sure, if she wasn’t old enough to be my mother.”

The conversation shifted, but Matteo couldn’t shake the feeling the name had stirred. As Juliette’s family called them back to the table, he pocketed his phone, a strange warmth lingering—part curiosity, part recognition.

To think that months before, all that technologie to connect dots together didn’t exist. People would spend years of research, now accessible in a matter of seconds.

Later that night, as they were waiting for the new year countdown, he found himself wondering: What kind of person would spend their retirement investing in forgotten villages and forgotten dreams? Someone who believed in second chances, maybe. Someone who, like him, was drawn to the idea of piecing together a life from scattered connections.

November 5, 2024 at 3:36 am #7581In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After leaving the clamour of her fellow witches behind, Frella took a moment to ground herself after the whirlwind of ideas and plans discussed during their meeting.

As she walked home, her thoughts drifted back to Herma’s cottage. The treasure trove of curiosities in the camphor chest had captivated her imagination, but the trips had grown tiresome, each journey stretching her time and energy. Instead, she gathered a few items to keep at her own cottage—an ever growing collection of mysterious postcards, a brass spyglass, some aged papers hinting at forgotten histories, and of course, the mirror. Each object hummed with potential, calling to her in quiet moments, urging her to dig deeper.

The treasures from Herma’s chest were scattered across her kitchen table; each object felt like a piece of a larger puzzle, and she was determined to fit them together.

As Frella settled into a chair, she felt a sudden urge to inspect the mirror; the thought of its secrets sent a thrill through her, albeit tinged with trepidation.

It was exquisite, its opalescent sheen casting soft reflections across the room. She held it up to the light, watching colours shift within the glass, swirling like a living entity.

“What do you wish to show me this time?” she whispered.

As she gazed into the mirror, her reflection blurred, and she felt a pull—a connection to the past. Images began to form, and Frella found herself once more staring at the same elderly woman, her silver hair wild and glistening.

As the vision settled around her, Frella felt the air shimmer with energy, and the scene began to shift again. She focused intently, eager to grasp every detail.

Oliver Cromwell sat at a grand wooden desk piled high with scrolls and papers, his quill poised in his hand and brow furrowed in concentration. The room bustled with activity—servants hurried to and fro, and shrill laughter floated in from outside, where a gathering seemed to be taking place.

“By the King’s beard, where is the ink?” Cromwell muttered, his voice a deep rumble. With a flourish, he dipped the quill into a small inkwell that looked suspiciously like it had been made from a goat’s hoof.

With great care, he began to write on a piece of parchment. The ornate script flowed from his quill, remarkably elegant despite the chaos around him.

“To my dearest friend,” he wrote, brow twitching with the effort of being both eloquent and succinct. “I trust this missive finds you well, though your ears may be ringing from the ruckus outside. We’ve recently triumphed over the King, and while my duties as Lord Protector keep me occupied, I have stolen a moment to compose this note.”

He paused, casting a wary glance around the room as if expecting eavesdroppers. “I must admit, I have developed a curious fondness for a young lady who claims she can commune with spirits. I suspect she may know a thing or two about the secret lives of witches. If you find yourself in town, perhaps we could investigate together? Bring wine. And if you can manage it, a decent snack. One can hardly strategise on an empty stomach.”

Cromwell’s mouth twitched into a wry smile as he added, “P.S. If you happen to encounter Seraphina, do inform her that I’ll return her mirror just as soon as I’m done with my… experiments. I fear she may not appreciate the ‘creative applications’ I’ve discovered for it.”

With a sigh of resignation, he sealed the parchment with an ornate wax stamp shaped like a owl. “Now, where did I see that errant messenger?” he grumbled, scanning the room irritably.

Frella placed the mirror gently back on the table, her heart pounding. She needed to unravel the mysteries linking her to Seraphina and Cromwell. The time for discovery was upon her, and with each passing moment, she felt the call of her ancestors echoing through the very fabric of her being.

But could she untangle the mystery before her fellow witches set off on yet another ill-fated adventure? She would have to make haste.

October 30, 2024 at 3:58 pm #7576In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After the postcard craze had passed, Frella returned to Herma’s cottage several times to study the camphor chest. Every day for a week, Herma let her into the living room, where she would sit quietly in front of the chest, sometimes for hours. The wood’s glossy surface would catch the light, warm and rich, like polished honey. Frella would trace the strange curves of the mysterious engravings with her fingers, feeling the subtle dips and rises beneath her touch. The patterns felt ancient, worn smooth in places, yet sharp along certain edges, as if holding onto secrets just out of reach.

Then, as she lifted the heavy lid, a soft creak would break the silence, the hinges groaning as if they hadn’t moved in ages. A burst of cool, earthy fragrance would immediately rise, filling the air with camphor’s sharp, clean scent, mingled with faint hints of aged cedar and spice.

It didn’t take long for Frella to notice that each time she opened the chest, she would find a new object among the old papers and postcards. It was never the same. Once, it was an old brass spyglass; another time, it might be an ornate compass with seven directions marked. Yet another day, she found a teddy bear. By some odd coincidence, each item always seemed to be something she needed in her life at that particular moment.

When Eris informed them that Malove was most likely under a powerful spell, Frella found the mirror. An inscription carved clumsily on its back read, “This Mystic Mirror belongs to Seraphina.” The mirror’s metal was cold, tarnished, and in need of a good polish. Jeezel would have surely raved about the intricate vines of silver and gold, twisting in delicate patterns that seemed to shift with the viewer’s perspective. But what captivated Frella most was the glass itself. It held a faint opalescent sheen, swirling with hints of colors, like a rainbow caught in crystal.

The first time Frella looked into it, she saw, behind her own reflection, an elderly woman with silver hair handing the mirror down to a little girl who looked just like Frella had as a child. The clothes were peculiar, and the room they stood in looked as if it belonged in a fantasy movie. Then the little girl began carefully carving something on the back of the mirror with what looked like a golden chisel. When she finally turned the mirror and looked into it, her reflection replaced Frella’s. She said something, but there was no sound. Frella had the distinct impression that the girl’s lips had formed the words, “We are the same. It’s yours now; you’ll need it soon.” Then she vanished, and Frella’s own reflection reappeared.

Still filled with awe at what just happened, Frella wondered if Seraphina was a long lost ancestor. “Was that chest also yours, Seraphina?” she asked in a whisper to the ghosts of the past.

February 5, 2024 at 8:08 pm #7350In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Eris did portal to be in person for the last Ritual. After all, Smoke Testing for incense making was the reverse expectation of what it meant in programming. You plug in a new board and turn on the power. If you see smoke coming from the board, turn off the power. You don’t have to do any more testing. But for witches, it just meant success. This one however revealed itself to be so glorious, she would have regretted sorely if she’d missed it.

“Someone tried to jinx my blog with black magic emojis! Quick, give me a Nokia!” Jeezel sharp cry was the innocent trigger that dominoed the whole ceremony into mayhem. With her clumsy hand gestures, she inadvertently elbowed Frigella as she was carefully counting the last drops of the resin, which spilled over to the nearby Bunsen burner.

From there, the sweet symphony of disaster that unfolded in the sanctified chamber of the coven could have been put to a choral version of Tchaikovsky’s Overture 1812, with climactic volley of cannon fire, ringing chimes, and brass fanfare. Only with smoke as sound effects.

In the ensuing chaos of the Fourth Rite, everything became quickly shrouded in a thick, billowing smoke, an unintended byproduct of the smoke test gone wildly awry. Truella, in her attempts to salvage the ceremony, darted through the room, a scorched piece of fabric clutched in her hand—her delicate pashmina shawl that did more fanning than smothering and now more charcoal than its original vibrant hue. Her expression teetered between horror and disbelief as she lamented her once-prized possession, now reduced to ashes.

Jeezel, ever the optimist, quickly came back to her senses choosing to find humor if not opportunity amidst disaster. Like a true diva emerging from the smoke effects, she held up a singed twig adorned with the remains of decorative leaves and announced with a wide grin, “Behold, the perfect accessory for the Autumn Pageant!” Her voice was muffled by the smog, her figure obscured save for the intermittent glint of her eyes as she wove through the smoke, brandishing the charred twig like a parade marshal’s baton.

Meanwhile, Eris was caught in a frenetic ballet, attempting to corral the smoke with sweeps of her arms and ancient spells, as if the very air could be tamed by her whims. Her efforts, while noble, only served to create an odd wind pattern that whirled papers and loose items into a miniature cyclone of confusion.

At the epicenter of the pandemonium stood Malové, the High Witch, her composure as livid as the flames that had sparked the debacle. Her normally unflappable demeanor crumbled as she surveyed the disarray, her voice rising above the cacophony, “Witches, have you mistaken this sacred rite for a comedy of errors?” Her words cut through the haze, sharp and commanding.

Frigella, caught off-guard by the commotion, scrambled to quell the smoky serpent that had coiled throughout the room. With a flick of her wand, she directed gusts of fresh air towards the smoke, but in her haste, the spell went askew, further fanning the chaos as parchments and ritual tools spun through the air like leaves in a storm.

All the witches assembled, not knowing how to respond, tried to grapple with the havoc.

There, in the mist of misadventure, the Fourth Rite of 2024 would be one for the annals, a tale to be told with a mix of chagrin and mirth for ages to come. And though Malové’s patience was tried, even the High Witch couldn’t deny the comedic spectacle that unfurled before her—a spectacle that would surely need to be remedied.

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

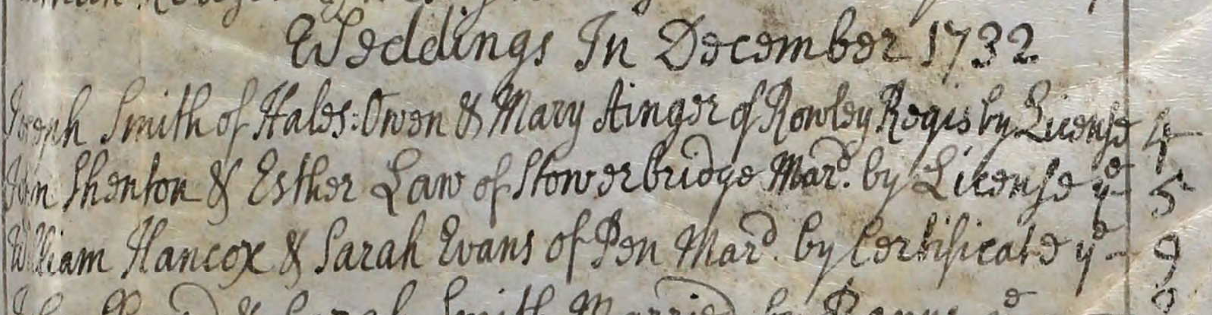

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

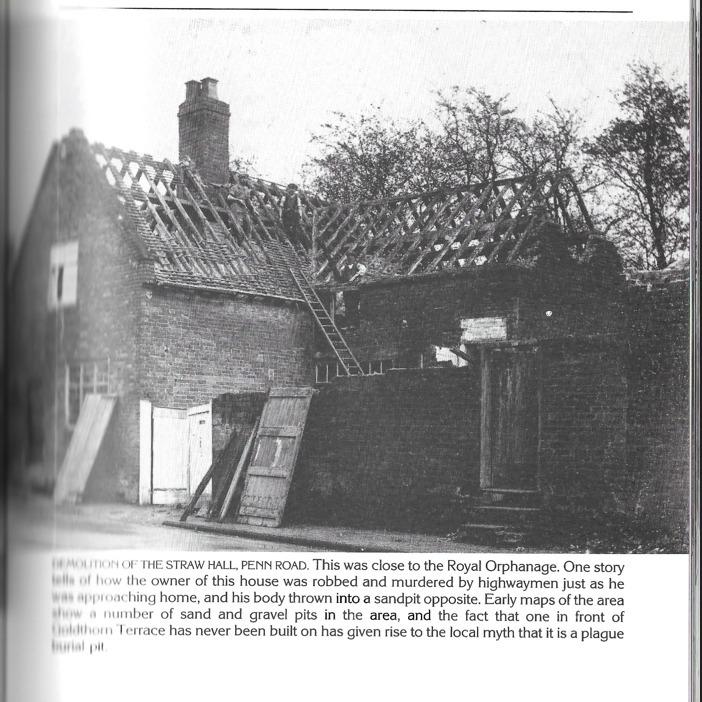

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

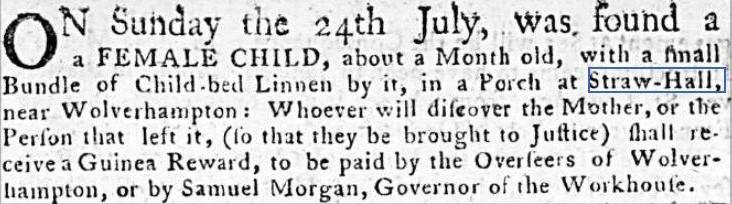

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

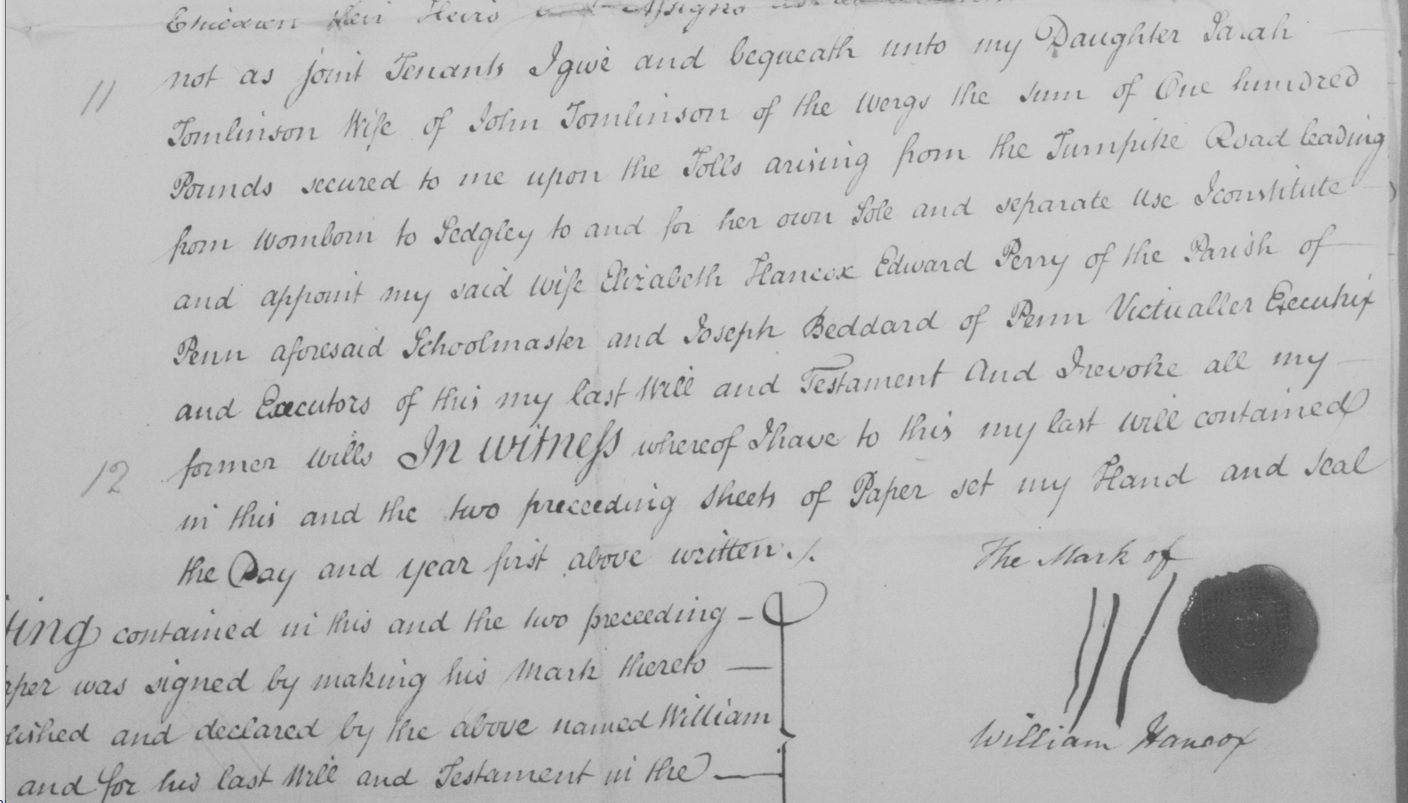

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wood Screw Manufacturers

The Fishers of West Bromwich.

My great grandmother, Nellie Fisher, was born in 1877 in Wolverhampton. Her father William 1834-1916 was a whitesmith, and his father William 1792-1873 was a whitesmith and master screw maker. William’s father was Abel Fisher, wood screw maker, victualler, and according to his 1849 will, a “gentleman”.

Nellie Fisher 1877-1956 :

Abel Fisher was born in 1769 according to his burial document (age 81 in 1849) and on the 1841 census. Abel was a wood screw manufacturer in Wolverhampton.

As no baptism record can be found for Abel Fisher, I read every Fisher will I could find in a 30 year period hoping to find his fathers will. I found three other Fishers who were wood screw manufacurers in neighbouring West Bromwich, which led me to assume that Abel was born in West Bromwich and related to these other Fishers.

The wood screw making industry was a relatively new thing when Abel was born.

“The screw was used in furniture but did not become a common woodworking fastener until efficient machine tools were developed near the end of the 18th century. The earliest record of lathe made wood screws dates to an English patent of 1760. The development of wood screws progressed from a small cottage industry in the late 18th century to a highly mechanized industry by the mid-19th century. This rapid transformation is marked by several technical innovations that help identify the time that a screw was produced. The earliest, handmade wood screws were made from hand-forged blanks. These screws were originally produced in homes and shops in and around the manufacturing centers of 18th century Europe. Individuals, families or small groups participated in the production of screw blanks and the cutting of the threads. These small operations produced screws individually, using a series of files, chisels and cutting tools to form the threads and slot the head. Screws produced by this technique can vary significantly in their shape and the thread pitch. They are most easily identified by the profusion of file marks (in many directions) over the surface. The first record regarding the industrial manufacture of wood screws is an English patent registered to Job and William Wyatt of Staffordshire in 1760.”

Wood Screw Makers of West Bromwich:

Edward Fisher, wood screw maker of West Bromwich, died in 1796. He mentions his wife Pheney and two underage sons in his will. Edward (whose baptism has not been found) married Pheney Mallin on 13 April 1793. Pheney was 17 years old, born in 1776. Her parents were Isaac Mallin and Sarah Firme, who were married in West Bromwich in 1768.

Edward and Pheney’s son Edward was born on 21 October 1793, and their son Isaac in 1795. The executors of Edwards 1796 will are Daniel Fisher the Younger, Isaac Mallin, and Joseph Fisher.There is a marriage allegations and bonds document in 1774 for an Edward Fisher, bachelor and wood screw maker of West Bromwich, aged 25 years and upwards, and Mary Mallin of the same age, father Isaac Mallin. Isaac Mallin and Sarah didn’t marry until 1768 and Mary Mallin would have been born circa 1749. Perhaps Isaac Mallin’s father was the father of Mary Mallin. It’s possible that Edward Fisher was born in 1749 and first married Mary Mallin, and then later Pheney, but it’s also possible that the Edward Fisher who married Mary Mallin in 1774 was Edward Fishers uncle, Daniel’s brother. (I do not know if Daniel had a brother Edward, as I haven’t found a baptism, or marriage, for Daniel Fisher the elder.)

There are two difficulties with finding the records for these West Bromwich families. One is that the West Bromwich registers are not available online in their entirety, and are held by the Sandwell Archives, and even so, they are incomplete. Not only that, the Fishers were non conformist. There is no surviving register prior to 1787. The chapel opened in 1788, and any registers that existed before this date, taken in a meeting houses for example, appear not to have survived.

Daniel Fisher the younger died intestate in 1818. Daniel was a wood screw maker of West Bromwich. He was born in 1751 according to his age stated as 67 on his death in 1818. Daniel’s wife Mary, and his son William Fisher, also a wood screw maker, claimed the estate.

Daniel Fisher the elder was a farmer of West Bromwich, who died in 1806. He was 81 when he died, which makes a birth date of 1725, although no baptism has been found. No marriage has been found either, but he was probably married not earlier than 1746.

Daniel’s sons Daniel and Joseph were the main inheritors, and he also mentions his other children and grandchildren namely William Fisher, Thomas Fisher, Hannah wife of William Hadley, two grandchildren Edward and Isaac Fisher sons of Edward Fisher his son deceased. Daniel the elder presumably refers to the wood screw manufacturing when he says “to my son Daniel Fisher the good will and advantage which may arise from his manufacture or trade now carried on by me.” Daniel does not mention a son called Abel unfortunately, but neither does he mention his other grandchildren. Abel may be Daniel’s son, or he may be a nephew.

The Staffordshire Record Office holds the documents of a Testamentary Case in 1817. The principal people are Isaac Fisher, a legatee; Daniel and Joseph Fisher, executors. Principal place, West Bromwich, and deceased person, Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

William and Sarah Fisher baptised six children in the Mares Green Non Conformist registers in West Bromwich between 1786 and 1798. William Fisher and Sarah Birch were married in West Bromwich in 1777. This William was probably born circa 1753 and was probably the son of Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

Daniel Fisher the younger and his wife Mary had a son William, as mentioned in the intestacy papers, although I have not found a baptism for William. I did find a baptism for another son, Eutychus Fisher in 1792.

In White’s Directory of Staffordshire in 1834, there are three Fishers who are wood screw makers in Wolverhampton: Eutychus Fisher, Oxford Street; Stephen Fisher, Bloomsbury; and William Fisher, Oxford Street.

Abel’s son William Fisher 1792-1873 was living on Oxford Street on the 1841 census, with his wife Mary and their son William Fisher 1834-1916.

In The European Magazine, and London Review of 1820 (Volume 77 – Page 564) under List of Patents, W Fisher and H Fisher of West Bromwich, wood screw manufacturers, are listed. Also in 1820 in the Birmingham Chronicle, the partnership of William and Hannah Fisher, wood screw manufacturers of West Bromwich, was dissolved.

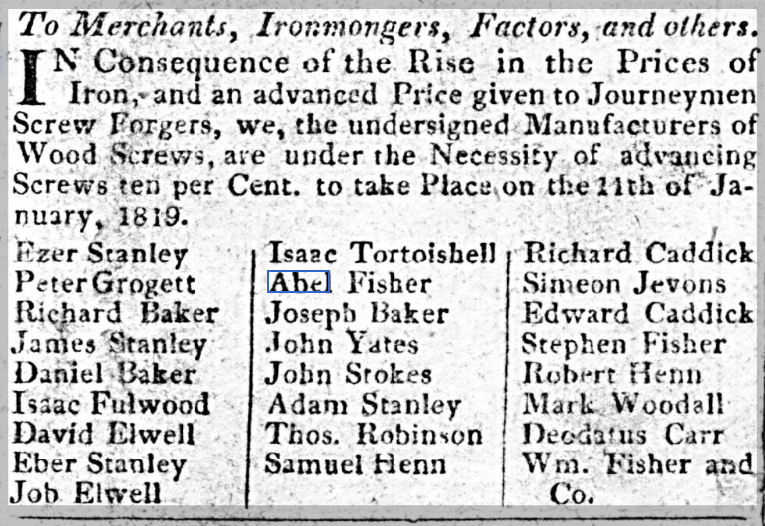

In the Staffordshire General & Commercial Directory 1818, by W. Parson, three Fisher’s are listed as wood screw makers. Abel Fisher victualler and wood screw maker, Red Lion, Walsal Road; Stephen Fisher wood screw maker, Buggans Lane; and Daniel Fisher wood screw manufacturer, Brickiln Lane.

In Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on 4 January 1819 Abel Fisher is listed with 23 other wood screw manufacturers (Stephen Fisher and William Fisher included) stating that “In consequence of the rise in prices of iron and the advanced price given to journeymen screw forgers, we the undersigned manufacturers of wood screws are under the necessity of advancing screws 10 percent, to take place on the 11th january 1819.”

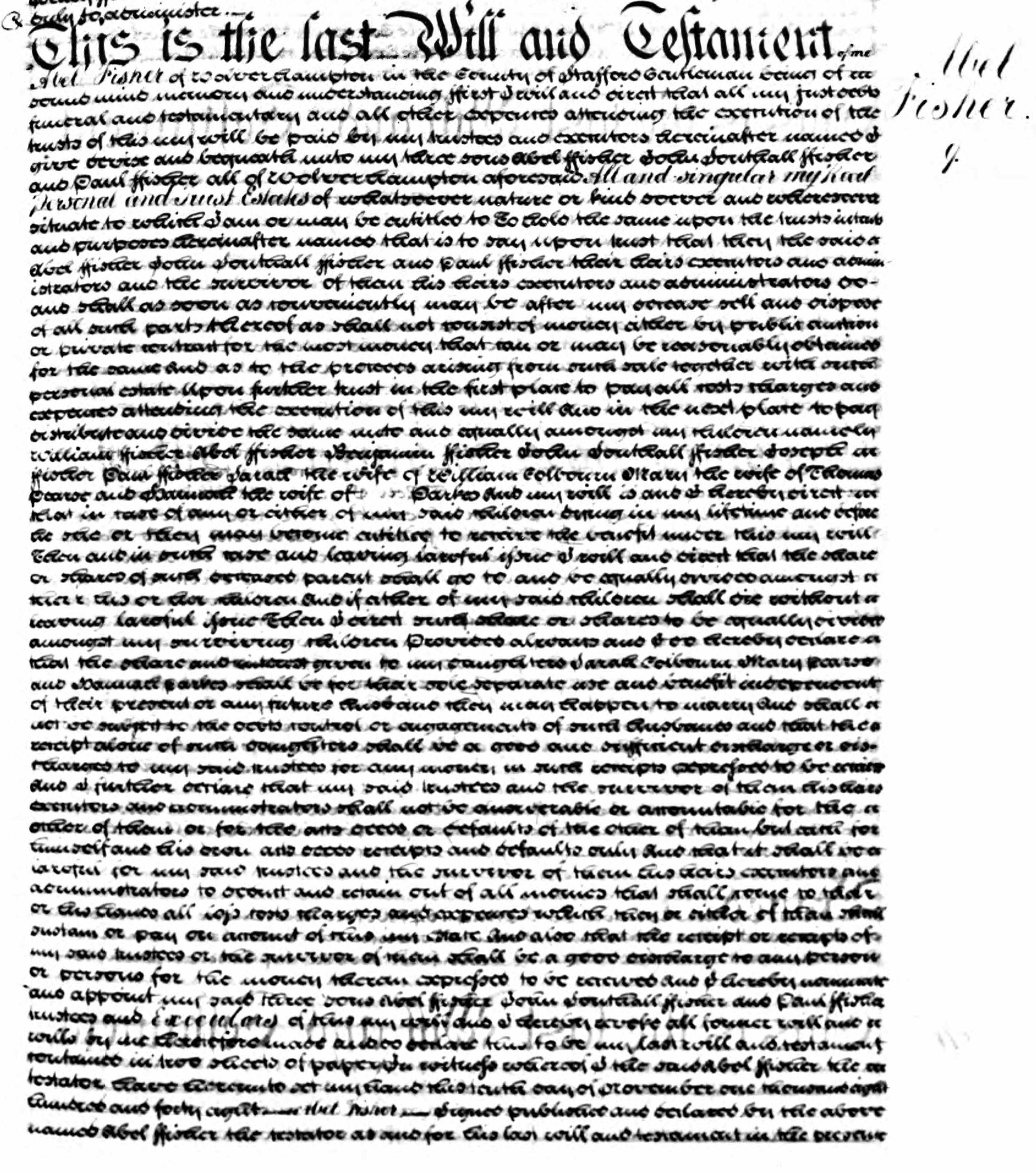

In Abel Fisher’s 1849 will, he names his three sons Abel Fisher 1796-1869, Paul Fisher 1811-1900 and John Southall Fisher 1801-1871 as the executors. He also mentions his other three sons, William Fisher 1792-1873, Benjamin Fisher 1798-1870, and Joseph Fisher 1803-1876, and daughters Sarah Fisher 1794- wife of William Colbourne, Mary Fisher 1804- wife of Thomas Pearce, and Susannah (Hannah) Fisher 1813- wife of Parkes. His son Silas Fisher 1809-1837 wasn’t mentioned as he died before Abel, nor his sons John Fisher 1799-1800, and Edward Southall Fisher 1806-1843. Abel’s wife Susannah Southall born in 1771 died in 1824. They were married in 1791.

The 1849 will of Abel Fisher:

August 15, 2023 at 12:42 pm #7267

August 15, 2023 at 12:42 pm #7267In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Thomas Josiah Tay

22 Feb 1816 – 16 November 1878

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.”

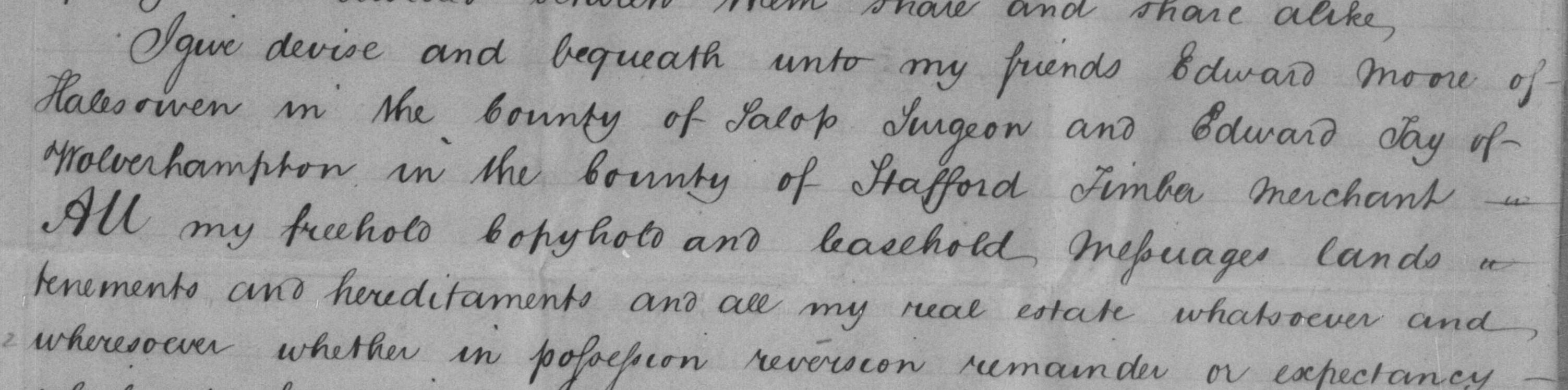

I first came across the name TAY in the 1844 will of John Tomlinson (1766-1844), gentleman of Wergs, Tettenhall. John’s friends, trustees and executors were Edward Moore, surgeon of Halesowen, and Edward Tay, timber merchant of Wolverhampton.

Edward Moore (born in 1805) was the son of John’s wife’s (Sarah Hancox born 1772) sister Lucy Hancox (born 1780) from her first marriage in 1801. In 1810 widowed Lucy married Josiah Tay (1775-1837).

Edward Tay was the son of Sarah Hancox sister Elizabeth (born 1778), who married Thomas Tay in 1800. Thomas Tay (1770-1841) and Josiah Tay were brothers.

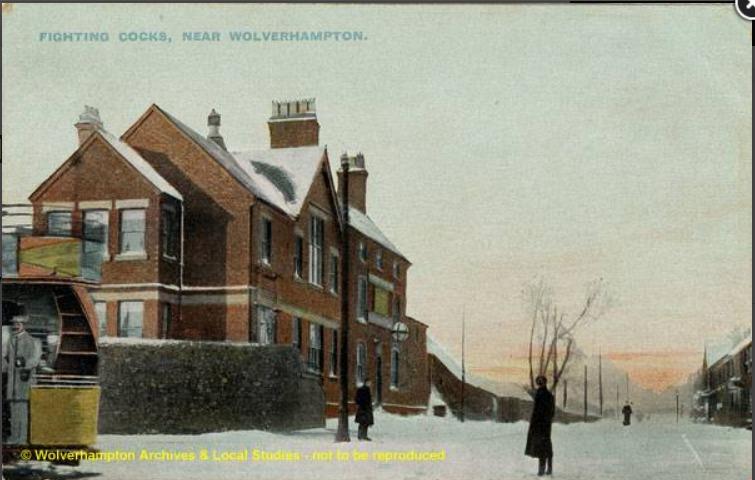

Edward Tay (1803-1862) was born in Sedgley and was buried in Penn. He was innkeeper of The Fighting Cocks, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, as well as a builder and timber merchant, according to various censuses, trade directories, his marriage registration where his father Thomas Tay is also a timber merchant, as well as being named as a timber merchant in John Tomlinsons will.

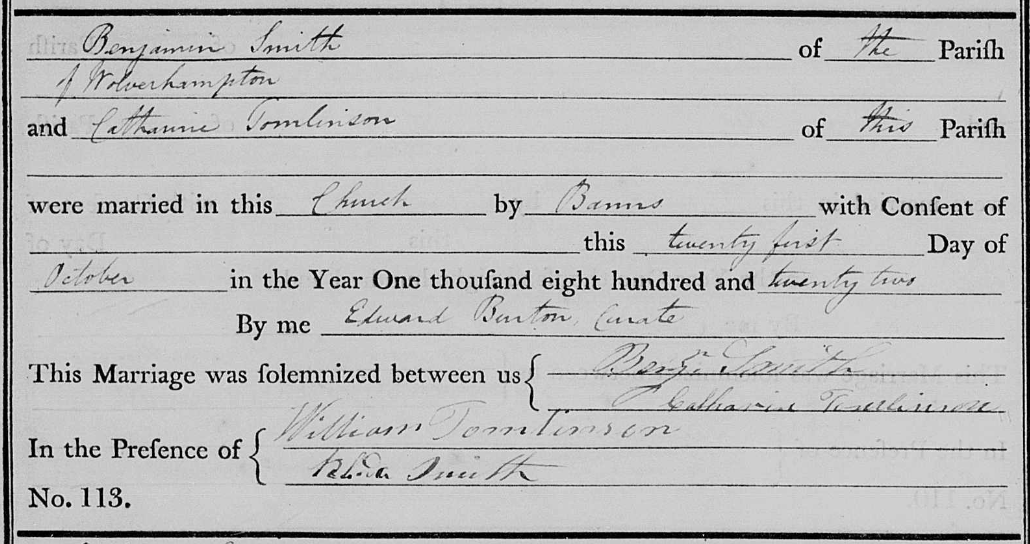

John Tomlinson’s daughter Catherine (born in 1794) married Benjamin Smith in Tettenhall in 1822. William Tomlinson (1797-1867), Catherine’s brother, and my 3x great grandfather, was one of the witnesses.

Their daughter Matilda Sarah Smith (1823-1910) married Thomas Josiah Tay in 1850 in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah Tay (1816-1878) was Edward Tay’s brother, the sons of Elizabeth Hancox and Thomas Tay.

Therefore, William Hancox 1737-1816 (the father of Sarah, Elizabeth and Lucy), was Matilda’s great grandfather and Thomas Josiah Tay’s grandfather.

Thomas Josiah Tay’s relationship to me is the husband of first cousin four times removed, as well as my first cousin, five times removed.

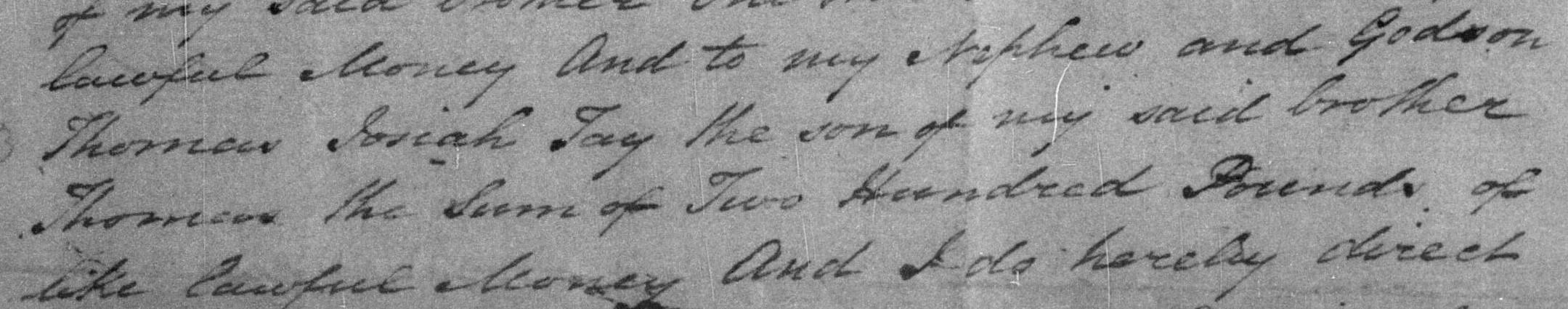

In 1837 Thomas Josiah Tay is mentioned in the will of his uncle Josiah Tay.

In 1841 Thomas Josiah Tay appears on the Stafford criminal registers for an “attempt to procure miscarriage”. He was found not guilty.

According to the Staffordshire Advertiser on 14th March 1840 the listing for the Assizes included: “Thomas Ashmall and Thomas Josiah Tay, for administering noxious ingredients to Hannah Evans, of Wolverhampton, with intent to procure abortion.”

The London Morning Herald on 19th March 1840 provides further information: “Mr Thomas Josiah Tay, a chemist and druggist, surrendered to take his trial on a charge of having administered drugs to Hannah Lear, now Hannah Evans, with intent to procure abortion.” She entered the service of Tay in 1837 and after four months “an intimacy was formed” and two months later she was “enciente”. Tay advised her to take some pills and a draught which he gave her and she became very ill. The prosecutrix admitted that she had made no mention of this until 1939. Verdict: not guilty.

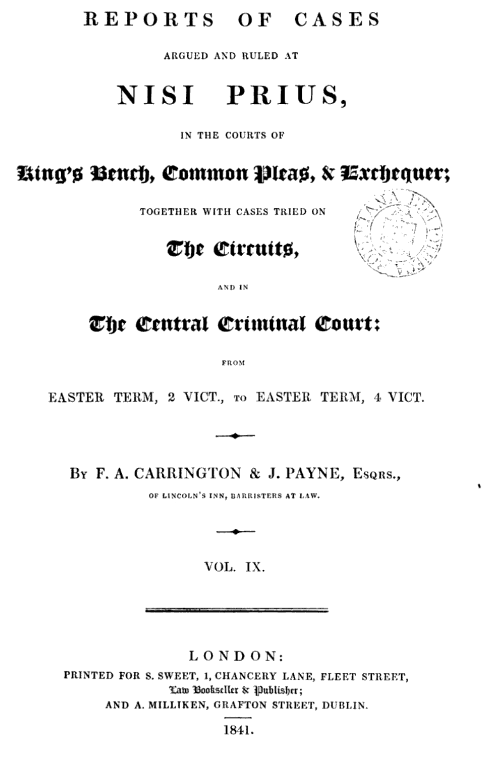

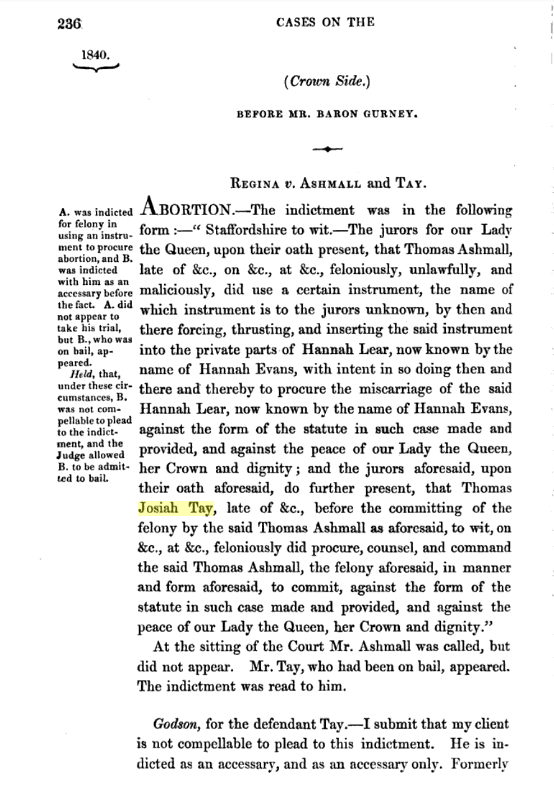

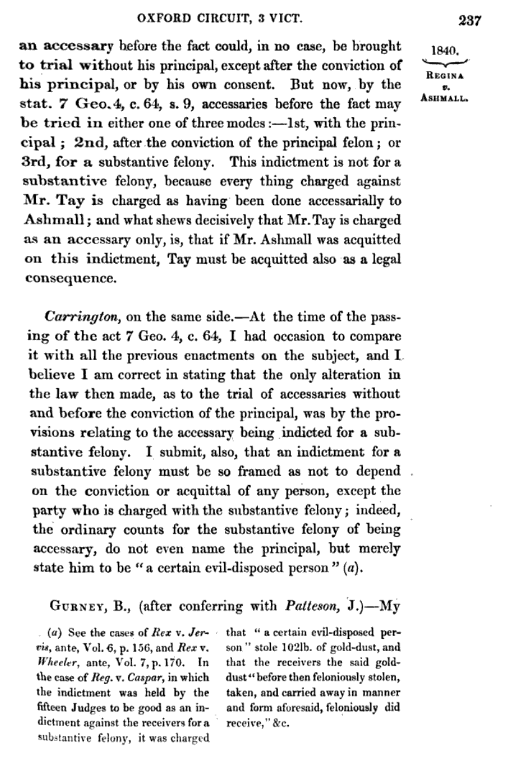

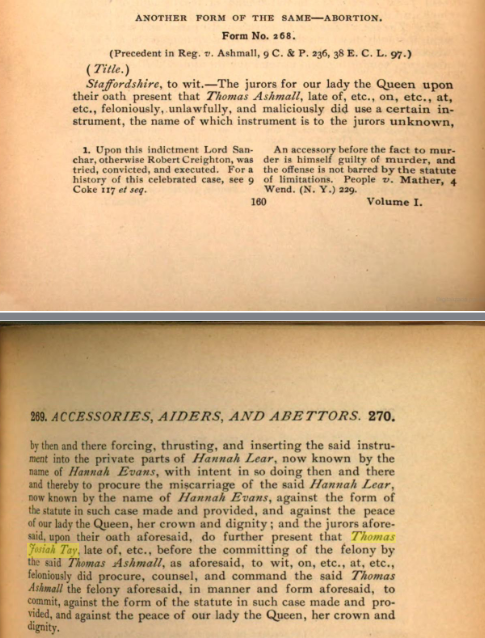

However, the case of Thomas Josiah Tay is also mentioned in a couple of law books, and the story varies slightly. In the 1841 Reports of Cases Argued and Rules at Nisi Prius, the Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case states that Thomas Ashmall feloniously, unlawfully, and maliciously, did use a certain instrument, and that Thomas Josiah Tay did procure the instrument, counsel and command Ashmall in the use of it. It concludes that Tay was not compellable to plead to the indictment, and that he did not.

The Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case is also mentioned in the Encyclopedia of Forms and Precedents, 1896.

In 1845 Thomas Josiah Tay married Isabella Southwick in Tettenhall. Two years later in 1847 Isabella died.

In 1850 Thomas Josiah married Matilda Sarah Smith. (granddaughter of John Tomlinson, as mentioned above)

On the 1851 census Thomas Josiah Tay was a farmer of 100 acres employing two labourers in Shelfield, Walsall, Staffordshire. Thomas Josiah and Matilda Sarah have a daughter Matilda under a year old, and they have a live in house servant.

In 1861 Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife and their four children Ann, James, Josiah and Alice, live in Chelmarsh, Shropshire. He was a farmer of 224 acres. Mercy Smith, Matilda’s sister, lives with them, a 28 year old dairy maid.

In 1863 Thomas Josiah Tay of Hampton Lode (Chelmarsh) Shropshire was bankrupt. Creditors include Frederick Weaver, druggist of Wolverhampton.

In 1869 Thomas Josiah Tay was again bankrupt. He was an innkeeper at The Fighting Cocks on Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, at the time, the same inn as his uncle Edward Tay, aforementioned timber merchant.

In 1871, Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife Matilda, and their three children Alice, Edward and Maryann, were living in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah was a commercial traveller.

He died on the 16th November 1878 at the age of 62 and was buried in Darlaston, Walsall. On his gravestone:

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.” Psalm XC 15 verse.

Edward Moore, surgeon, was also a MAGISTRATE in later years. On the 1871 census he states his occupation as “magistrate for counties Worcester and Stafford, and deputy lieutenant of Worcester, formerly surgeon”. He lived at Townsend House in Halesowen for many years. His wifes name was PATTERN Lucas. Her mothers name was Pattern Hewlitt from Birmingham, an unusal name that I have not heard before. On the 1871 census, Edward’s son was a 22 year old solicitor.

In 1861 an article appeared in the newspapers about the state of the morality of the women of Dudley. It was claimed that all the local magistrates agreed with the premise of the article, concerning unmarried women and their attitudes towards having illegitimate children. Letters appeared in subsequent newspapers signed by local magistrates, including Edward Moore, strongly disagreeing.

Staffordshire Advertiser 17 August 1861:

June 8, 2023 at 8:10 am #7254

June 8, 2023 at 8:10 am #7254In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“Oh!” exclaimed Liz, who had heretofore been struggling to stay abreast of recent developments. “You mean Mr Du Grat! Honestly Finnley, your pronunciation leaves much to be desired. I have it from the horses mouth that the charming Mr Du Grat has gone on an adventure. More’s the pity,” she added, “As I was just starting to take a shine to him.”

“But what about Walter Melon?” Roberto chimed in nervously.

“What’s it got to do with you?” Liz narrowed her eyes. “Turning the garden into a wildlife haven was a mistake, it’s left you with far too much time on your hands, my boy! See if there’s anything you can do to help Finnley, it might stop her screaming.”

“Why not help her with the baby faced cookies, Roberto?” Godfrey said mildly, peering over the top of his spectacles.

“What was that you said? I can’t hear over that racket.”

“I SAID..” Godfrey shouted, but was prevented from continuing when the corner of Liz’s desk landed on his gouty toe, which left him momentarily speechless.

“Well that shut you all up, didn’t it!” With a triumphant smile, Liz surveyed the room. Her sudden urge to upend her desk, sending papers, books, ashtrays, peanuts and coffee cups scattering all over the room had been surprisingly therapeutic. “I must do that more often,” she said quietly to herself.

“I heard that,” retorted Finnley. “Let’s see how therapeutic it is to clean it all up.” And with that, Finnley marched out of the room, tossing her toilet plunger over her shoulder which hit Godfrey on the side of his head knocking his glasses off.

“Not so fast, Finnely! Godfrey shouted. The pain in his big toe had enraged him. But it was too late, the insubordinate wench slammed the door behind her and thundered up the stairs.

“Ah, Roberto! You can clean all this mess up. I’m off to the dentist for a bit of peace and quiet. I’ll expect it all to be tip top and Bristol fashion when I get back.”

Thundering back down the stairs, Finnley flung the door open. “You use far too many cliches!” and then slammed back out again.

May 12, 2023 at 8:15 pm #7237In reply to: Washed off the sea ~ Creative larks

“Sod this for a lark,” he said, and then wondered what that actually meant. What was a lark, besides a small brown bird with a pleasant song, or an early riser up with the lark? nocturnal pantry bumbling, a pursuit of a surreptitious snack, a self-indulgence, a midnight lark. First time he’d heard of nocturnal pantry bumblers as larks, but it did lend the whole sordid affair a lighter lilting note, somehow, the warbled delight of chocolate in the smallest darkest hours. Lorries can be stolen for various purposes—sometimes just for a lark—and terrible things can happen. But wait, what? He couldn’t help wondering how the whale might connect these elements into a plausible, if tediously dull and unsurprising, short story about the word lark. Did I use too many commas, he wondered? And what about the apostrophe in the plural comma word? I bet AI doesn’t have any trouble with that. He asked who could think of caging larks that sang at heaven’s gates. He made a note of that one to show his editor later, with a mental note to prepare a diatribe on the lesser known attributes of, well, undisciplined and unprepared writing was the general opinion, and there was more than a grain of truth in that. Would AI write run on sentences and use too many whataretheycalled? Again, the newspapers tell these children about pills with fascinating properties, and taking a pill has become a lark. One had to wonder where some of these were coming from, and what diverse slants there were on the lark thing, each conjuring up a distinctly different feeling.

Suddenly he had an idea.

April 18, 2023 at 5:23 pm #7226In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“I worry about the dreadful limbo, those poor characters! So much going on and there they all are, frozen in time, perched on the edge of all those cliffs, waiting to spring into action, leap across chasms of revelations, lurch into dark mysterious depths…” Liz trailed off, looking pensively out of the window. “I wonder if the characters will ever forgive me for the jerky spasms of action followed by interminable stretches of oblivion, endlessly repeated…. Oh dear, oh dear! What a terrible torment, taunting them with great unveilings, and then… then, the desertion, forsaken yet again, abandoned …. and for what?”

“Attending to other pressing matters in real life?” offered Finnley. “Entertaining guests? Worrying about aged relatives?” Liz interrupted with a cross between a snort and a harumph. “Writing shopping lists?” Finnley continued, a fount of gently patient sagacity. Bless that girl, thought Liz, uncharacteristically generous in her assessment of the often difficult maid. “Do you even know if they’re aware of the dilated gaps in the narrative?”

Liz was momentarily nonplussed. This was something she had heretofore not considered. “You mean they might not be waiting?”

“That’s right”, Finnley replied, warming to the idea that she hadn’t given much thought to, and had just thrown into the conversation to mollify Liz, who was in danger of droning on depressingly for the rest of the evening. “They probably don’t even notice, a bit like blinking out, and then springing back into animation. I wouldn’t worry if I were you. Why don’t you ask them and see what they say?”

“Ask them?” repeated Liz stupidly. I really am getting dull in the head, she thought to herself and wondered why Finnley was smirking and nodding. Was the dratted girl reading her mind again? “Fetch me something to buck me up, Finnley. And fetch Roberto and Godfrey in here. Oh and bring a tray of whatever you’re bringing me, to buck us all up.” Liz looked up and smiled magnanimously into Finnley’s face. “And one for yourself, dear.”

Tidying the stack of papers on her desk into a neat pile and blowing the ash and crumbs off, Liz felt a plan forming. They would have a meeting with the characters and discuss their feelings, their hopes and ambitions, work it all out together. Why didn’t I think of this before? she wondered, quite forgetting that it was Finnley’s idea.

March 24, 2023 at 10:05 am #7215In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Zara the game character was standing in the entrance hallway in the old wooden inn. There was nobody around except for her three friends, and the light inside was strangely dim and an eerie orange glow was coming from the windows. She and the others wandered around opening doors and looking in rooms in the deserted building. There were a dozen or so bedrooms along both sides of a corridor, and a kitchen, dining room and lounge room leading off the entrance hall. Zara looked up the wide staircase, but as a cellar entrance was unlikely to be upstairs, she didn’t go up. The inn was surrounded by a wrap around verandah; perhaps the cellar entrance was outside underneath it. Zara checked for a personal clue:

“Amidst the foliage and bark, A feather and a beak in the dark.”

Foliage and bark suggested that the entrance was indeed outside, given the absence of houseplants inside. She stepped out the door and down the steps, walking around the perimeter of the raised vernadah, looking for a hatch or anything to suggest a way under the building. Before she had completed the circuit she noticed an outbuilding at the back underneath a eucalyptus tree and made her way over to it. She pushed the door open and peered into the dim interior. A single unmade bed, some jeans and t shirts thrown over the back of a chair, a couple of pairs of mens shoes….Zara was just about to retreat and close the door behind her when she noticed the little wooden desk in the corner with an untidy pile of papers and notebooks on it.

Wait though, Zara reminded herself, This is supposed to be a group quest. I better call the others over here.

Nevertheless, she went over to the desk to look first. There was an old fashioned feather quill and an ink pot on the desk, and a gold pocket watch and chain. Or was it a compass? Strangely, it seemed like neither, but what was it then? Zara picked one of the notebooks up but it was too dark inside the hut to read.

March 15, 2023 at 4:27 pm #7167In reply to: The Chronicles of the Flying Fish Inn

I can’t believe the cart race is tomorrow. Joe, Callum and I have worked so hard this year to incorporate solar panels and wind propellers to our little bijou. The cart race rules are clear, apart from thermal engines and fossil fuels, your imagination is your limit. Our only worry was that dust storm. We feared the Mayor would cancelled the race, but I think she won’t. She desperately needs the money.

Some folks thought to revive the festival as a prank fifteen years ago, but people had so much fun the council agreed to renew it the next year, and the year after that it was made official. It’s been a small town festival for ten years, and would have stayed like that if it hadn’t been for a bus full of Italian tourist on their way to Uluru. It broke down as they drove through main street – I remember it because I just started my job at the garage and couldn’t attend the race. Those Italians, a bunch of crazy people, posted videos of the race on the Internet and it went viral, propelling our ghost town to worldwide fame. We thought it would subside but some folks created a FishBone group and we’re almost as famous as Punxsutawney once a year. We even have a team of old ladies from Tikfijikoo Island.

All that attention attracted sponsors, mostly booze brands. But this year we’ve got a special one from Sidney. Aunt Idle who’s got a special friend at the city council told us the council members couldn’t believe it when the tart called and offered money. Botty Banworth, head of a big news company made famous by her blog: Prudish Beauty.

Aunt Idle, who heard it from one of her special friends at the town’s council, started a protest because she thought the Banworth tart would force the council to ban all recreational substances. But I have it from Callum, who’s the Mayor’s son, that the tart is not interested in making us an example of sobriety. She’s asked to lease the land where the old mines are and the Mayor haven’t told anybody about it.

After Callum told me about the lease, it reminded me about the riddle.

A mine, a tile, dust piled high,

Together they rest, yet always outside.

One misstep, and you’ll surely fall,

Into the depths, where danger lies all.Then something else happened. Another woman stopped at the gas station earlier today. I recognised one of the Inn’s guests, the one with the Mercedes. With her mirror sunglasses and her headscarf wrapped around her hair, she already looked suspicious. But as it happened, she asked me about the mines and how to go there. For abandoned mines, they sure attract a lot of attention.

It reminded me of something. So after work, I went to the Inn and asked the twins permission to go up to their lair. When dad disappeared, Mater went mad, she threw everything to the garbage. The twins waited til she got back inside and moved everything back in the attic and called it their lair. It looks just like dad’s old office with the boxes full of papers, the mahogany desk and even his typewriter. For whatever reason, Mater just ignores it and if she needs something from the attic, she asks someone else to get it, pretexting she can’t climb all those stairs.

I was right. Dad left the old manuscript he was working on at the time. A sci-fi novel about strange occurrences in an abandoned mine that looked just like the one outside of town. Prune said it’s badly written, and it doesn’t even have a title. But I remember having nightmares after reading some of the passages.

February 28, 2023 at 1:14 pm #6720In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“It’s amazing, all the material we gathered over the years, it makes one’s head spin…” Godfrey was poring over quantities of papers, mostly early drafts stuck haphazardly in a pile of donations boxes that Elizabeth had generously contributed to the National Library’s archives of great works and renowned authors, but mostly as way of spring cleaning.

He had materialized some of the links from the pages with webs of purple yarn tied to the wall of the dining hall. It had soon become a tangled mess of interwoven threads that he had to protect from the cleaning frenzied assaults of energetic feather duster of Finnley.

She’d softened her stance a little when she’s realised how often her namesake has popped in the various storylines, almost making her emotional about Liz’ incorporating her in her works of fictions —only to remember that most of the time, she’d been the working hand behind the continuity, the Finnleys appearances being an offshoot of this endeavour.

Godfrey had almost forgotten he was actually a publisher to start with, before he became more of a useful side-kick, if not a useful idiot.

The phone rang in the empty hall. Soon after, Finnley arrived with the heavy bakelite telephone, handing it over to Godfrey unceremoniously. “You might want to take this, it’s Felicity…” she mouthed the last word like it was the name of the Devil himself.

“Dear Flove protect us, don’t tell me Liz’ mother is in town…”

“Well, at least she has comic relief value” snorted Finnley on her way back to her duties.

January 22, 2023 at 11:35 am #6447In reply to: Newsreel from the Rim of the Realm

Miss Bossy sat at her desk, scanning through the stack of papers on her desk. She was searching for the perfect reporter to send on a mission to investigate a mysterious story that had been brought to her attention. Suddenly, her eyes landed on the name of Samuel Sproink. He was new to the Rim of the Realm Newspaper and had a reputation for being a tenacious and resourceful reporter.

She picked up the phone and dialed his number. “Sproink, I have a job for you,” she said in her gruff voice.

“Yes, Miss Bossy, what can I do for you?” Samuel replied, his voice full of excitement.

“I want you to go down to Cartagena, Spain, in the Golden Banana off the Mediterranean coast. There have been sightings of Barbary macaques happening there and tourists being assaulted and stolen only their shoes, which is odd of course, and also obviously unusual for the apes to be seen so far off the Strait of Gibraltar. I want you to get to the bottom of it. I need you to find out what’s really going on and report back to me with your findings.”

“Consider it done, Miss Bossy,” Samuel said confidently. He had always been interested in wildlife and the idea of investigating a mystery involving monkeys was too good to pass up.

He hang up the phone to go and pack his bags and head to the airport, apparently eager to start his investigation.

“Apes again?” Ricardo who’s been eavesdropping what surprised at the sudden interest. After that whole story about the orangutan man, he thought they’d be done with the menagerie, but apparently, Miss Bossy had something in mind. He would have to quiz Sweet Sophie to remote view on that and anticipate possible links and knots in the plot.

January 17, 2023 at 9:06 pm #6410In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Real-life Xavier was marveling at the new AL (Artificial Life) developments on this project he’d been working on. It’s been great at tidying the plot, confusing as the plot started to become with Real-life characters named the same as their Quirky counterparts ones.

Real-life Zara had not managed to remain off the computer for very long, despite her grand claims to the contrary. She’d made quick work of introducing a new player in the game, a reporter in an obscure newspaper, who’d seemed quirky enough to be their guide in the new game indeed. It was difficult to see if hers was a nickname or nom de plume, but strangely enough, she also named her own character the same as her name in the papers. Interestingly, Zara and Glimmer had some friends in common in Australia, where RL Zara was living at the moment.

Anyways… “Clever AL” Xavier smiled when he saw the output on the screen. “Yasmin will love a little tidiness; even if she is the brains of the group, she has always loved the help.”

Meanwhile, in the real world, Youssef was on his own adventure in Mongolia, trying to uncover the mystery of the Thi Gang. He had been hearing whispers and rumors about the ancient and powerful group, and he was determined to find out the truth. He had been traveling through the desert for weeks, following leads and piecing together clues, and he was getting closer to the truth.

Zara, Xavier, and Yasmin, on the other hand, were scattered around the world. Zara was in Australia, working on a conservation project and trying to save a group of endangered animals. Xavier was in Europe, working on a new project for a technology company. And Yasmin was in Asia, volunteering at a children’s hospital.

Despite being physically separated, the four friends kept in touch through video calls and messages. They were all excited about the upcoming adventure in the Land of the Quirks and the possibility of discovering their inner quirks. They were also looking forward to their trip to the Flying Fish Inn, where they hoped to find some clues about the game and their characters.

In the game, Glimmer Gambol’s interactions with the other characters will be taking place in the confines of the Land of the Quirks. As she is the one who has been playing the longest and has the most experience, she will probably be the one to lead the group and guide them through the game. She also has some information that the others don’t know about yet, and she will probably reveal it at the right time.

As the game and the real-world adventures are intertwined, the characters will have to navigate both worlds and find a way to balance them. They will have to use their unique skills and personalities to overcome challenges and solve puzzles, both in the game and in the real world. It will be an exciting and unpredictable journey, full of surprises and twists.

-

AuthorSearch Results