Search Results for 'street'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 21, 2023 at 6:35 pm #6617

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Youssef had brought his black obsidian with him in the kitchen at breakfast. Idle—Youssef had realised that on top of being her way of life, it was also her name—was preparing a herbal brownie under the supervision of a colourful parrot perched on her shoulder.

“If you’re interested in rocks, you should go to Betsy’s. She’s got that ‘Gems & Minerals’ shop on Main street. She opened it with her hubby a few years back. Before he died.”

“Nutty Betsy, Pretty Girl likes her better,” said the parrot.

Idle looked at his backpack and his clothes.

“You seem the wandering type, lad. I was like you when I was younger, always gallivanting here, there, and everywhere with my brother. Now, I prefer wandering in my mind, if you know what I mean,” she said licking her finger full of chocolate. “Anyway, an advice. Don’t go down the mines alone. Betsy’s hubby’s still down there after one of the tunnels collapsed a few years back. She’s not been quite herself ever since.”

Main street was —well— the only street in town. They’ve been preparing for some kind of festival, putting banners on top of the shops and in between two trees near the gas station. Youssef stopped there to buy snacks that he stacked on top of the obsidian stone in his backpack. The young boy who worked there, Devan, seemed quite excited at the perspective of the Lager and Cart Race. It happened only every ten years and last time he was too young to participate.

The shop had not been difficult to find, at the other end of the street. A tiny sign covered in purple star sequins indicated “Betsy’s Gems & Minerals — We deliver worldwide”. He felt with his hand the black rock he had put in his backpack. If Idle had not mentioned the mines and the dead husband, Youssef might have reconsidered going in. But the coincidence with his dream and the game was too intriguing. He entered.

The shop was a mess. Crates full of stones, cardboard boxes and bubble wrappings. In the back, a plump woman, working on a giant starfish she held on her lap, was humming as she listened to loud rock music. Youssef recognised a song from the Last Shadow Puppets’ second album : The Element of Surprise. Apparently, the woman hadn’t heard him enter. She wore a dress and a hat sprinkled with golden stars, and her wrists were hidden under a ton of stone bracelets. The music track changed. The woman started shaking her head following the rhythm of the tune. She was gluing small red stones, she picked in a little box, on one of the starfish arms.

The shop was a mess. Crates full of stones, cardboard boxes and bubble wrappings. In the back, a plump woman, working on a giant starfish she held on her lap, was humming as she listened to loud rock music. Youssef recognised a song from the Last Shadow Puppets’ second album : The Element of Surprise. Apparently, the woman hadn’t heard him enter. She wore a dress and a hat sprinkled with golden stars, and her wrists were hidden under a ton of stone bracelets. The music track changed. The woman started shaking her head following the rhythm of the tune. She was gluing small red stones, she picked in a little box, on one of the starfish arms.“Bad Habits! Uhu. Bad Habits! Uhu.”

Youssef moved closer. His shadow covered the starfish. The woman raised her head and screamed, scattering the red stones in her workshop. The starfish fell from her lap onto the ground with a thud.

“Oh! My! Little devil. Look at what you made me do. I lost my marbles,” she said with a high pitched laugh. “Your mother never taught you? That’s bad habit to creep up on people like that. You scared the sheep out of me!”

“I’m so sorry,” said Youssef, getting on his knees to help her gather the stones.

When they were all back in their box, Youssef got back on his feet. The woman looked a him with a softened face.

“You such a cutie with your bear shirt. You make me think of my Howard. He was as tall as you are. I’m Betsy, obviously” she said with a giggle, extending her hand to him.

They shook hands, making the pearls of her bracelets clink together.

“I’m Youssef.”

Youssef didn’t need to insist too much. Betsy was a real juke box of gossips. He just had to ask one question from time to time, and she would get going again. He was starting to feel his quirk could be more than a curse after all.

“When the tunnel collapsed,” Betsy said, “I was ready to give up the stone shop. The pain was too much to bear, everything in the shop reminded me of Howard. And in a miners’ town, who would want to buy stones anyway. We’ve been in bad terms with Idle and her family for some time, but that tragic incident coincided with her brother Fred’s disappearance. They thought at first Fred had died in the mines with Howard, because they spent so much time discussing together in Room 8 at the Inn. I overheard them once, talking about something they found in the mines. But Howard never told me, he was so secretive about that. We even had a fight, you know. But Fred, the children found some message later that suggested he had just left the family. Imagine, the children! Idle was pissed with him of course. Abandoning her with that mother of theirs and that money pit of an Inn and the rest of the family. And I needed company. So we started to get together on a regular basis. She would bring her special cakes, and we would complain about our lives. At some point she got involved with that shamanic stuff she found online, and she helped me find my totem Bear. It was quite a revelation. Bear suggested I diversify and open an online shop and start making orgonites. I love those little gummy bears so much. So, I followed Bear’s advice and it has been working like a charm ever since. That’s why I trusted you straight away, lad. Not ’cause of your cute face. You got the Bear in your heart,” she said putting her finger at the center of his chest.

My inner Bear, of course, thought Youssef. That’s the magnet. His phone buzzed. He took it out and saw he had an alert from the game and a message from his friends.

You found the source of your quirk, the magnetic pull that attracts talkative people to you.

Now obtain the silver key in the shape of a tongue to fulfil your quest.Zara : Where are you!?

We’re at the bar, getting parched! They got Pale Ale!

We’re at the bar, getting parched! They got Pale Ale!“I have to go,” said Youssef.

“Wait,” said Betsy.

She foraged through her orgonite collection and handed Youssef one little gummy bear and an ornate metal badge.

“Bear wants me to give this to you. Howard made it. He said it was his forked tongue key.”

She looked at him, emotion in her eyes.

“I know you won’t listen if I tell you not to. So, be careful when you go into the mines.”

February 21, 2023 at 9:10 am #6615

February 21, 2023 at 9:10 am #6615In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Like ships in the night, Zara and Yasmin still hadn’t met up with Xavier and Youssef at the inn. Yasmin was tired from traveling and retired to her room to catch up on some sleep, despite Zara’s hopes that they’d have a glass of wine or two and discuss whatever it was that was on Yasmins mind. Zara decided to catch up on her game.

The next quirk was “unleash your hidden rudeness” which gave Zara pause to consider how hidden her rudeness actually was. But wait, it was the avatar Zara, not herself. Or was it? Zara rearranged the pillows and settled herself on the bed.

Zara found her game self in the bustling streets of a medieval market town, visually an improvement on the previous game level of the mines, which pleased her, with many colourful characters and intriguing alleyways and street market vendors.

She quickly forgot what her quest was and set off wandering around the scene. Each alley led to a little square and each square had gaily coloured carts of wares for sale, and an abundance of grinning jesters and jugglers. Although tempted to linger and join the onlookers jeering and goading the jugglers and artistes that she encountered, Zara continued her ramble around the scene.

She came to a gathering outside an old market hall, where two particularly raucous jesters were trying to tempt the onlookers into partaking of what appeared to be cups of tea. Zara wondered what the joke was and why nobody in the crowd was willing to try. She inched closer, attracting the attention of the odd grinning fellow in the orange head piece.

“Come hither, ye fine wench in thy uncomely scant garments, I know what thou seekest! Pray, sit thee down beside me and partake of my remedy.”

“Who, me?” asked Zara, looking behind her to make sure he wasn’t talking to someone else.

“Thoust in dire need of my elixir, come ye hither!”

Somewhat reluctantly Zara stepped towards the odd figure who was offering to hand her a cup. She considered the inadvisability of drinking something that everyone else was refusing, but what the hell, she took the cup and saucer off him and took a hesitant sip.

The crowd roared with laughter and there was much mirthful thigh slapping when Zara spit the foul tasting concoction all over the jesters shoes.

“Believe me dame,” quoth the Jester, “I perceive proffered ware is worse by ten in the hundred than that which is sought. But I pray ye, tell me thy quest.”

“My quest is none of your business, and your tea sucks, mister,” Zara replied. “But I like the cup.”

Pushing past the still laughing onlookers and clutching the cup, Zara spotted a tavern on the opposite side of the square and made her way towards it. A tankard of ale was what she needed to get rid of the foul taste lingering in her mouth.

The inside of the tavern was as much a madhouse as the streets outside it. What was everyone laughing at? Zara found a place to sit on a bench beside a long wooden table. She sat patiently waiting to be served, trying to eavesdrop to decipher the cause of such merriment, but the snatches of conversation made no sense to her. The jollity was contagious, and before long Zara was laughing along with the others. A strange child sat down on the opposite bench (she seemed familiar somehow) and Zara couldn’t help remarking, “You lot are as mad as a box of frogs, are you all on drugs or something?” which provoked further hoots of laughter, thigh slapping and table thumping.

“Ye be an ungodly rude maid, and ye’ll not get a tankard of ale while thoust leavest thy cup of elixir untasted yet,” the child said with a smirk.

“And you are an impertinent child,” Zara replied, considering the potential benefits of drinking the remainder of the concoction if it would hasten the arrival of the tankard of ale she was now craving. She gritted her teeth and picked up the cup.

But the design on the cup had changed, and now bore a strange resemblance to Xavier. Not only that, the cup was calling her name in Xavier’s voice, and the table thumping got louder.

“Zara!” Xavier was knocking on her bedroom door. “Zara! We’re going for a beer in the local tavern, are you coming?”

“Xavi!” Zara snapped back to reality, “Yes! I’m bloody parched.”

February 18, 2023 at 11:28 am #6551In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Xavier had woken up in the middle of the night that felt surprisingly alive bursting with a quiet symphony of sounds from nocturnal creatures and nearby nature, painted on a canvas of eerie spacious silence.

It often took him a while to get accustomed to any new place, and it was not uncommon for him to have his mind racing in the middle of the night. Generally Brytta had a soothing presence and that often managed to nudge him back to sleep, otherwise, he would simply wake up until the train of thoughts had left the station.

It was beginning of the afternoon in Berlin; Brytta would be in a middle of a shift, so he recorded a little message for her to find when she would get back to her phone. It was funny to think they’d met thanks to Yasmin and Zara, at the time the three girls were members of the same photography club, which was called ‘Focusgroupfocus’ or something similar…

With that done, he’d turned around for something to do but there wasn’t much in the room to explore or to distract him sufficiently. Not even a book in the nightstand drawer. The decoration itself had a mesmerising nature, but after a while it didn’t help with the racing thoughts.He was tempted to check in the game — there was something satisfactory in finishing a quest that left his monkey brain satiated for a while, so he gave in and logged back in.

Completing the quest didn’t take him too long this time. The main difficulty initially was to find the portal from where his avatar had landed. It was a strange carousel of blue storks that span into different dimensions one could open with the proper incantation.

As usual, stating the quirk was the key to the location, and the carousel portal propelled him right away to Midnight town, which was clearly a ghost town in more ways than one. Interestingly, he was chatting on the side with Glimmer, who’d run into new adventures of her own while continuing to ask him what was up, and as soon as he’d reached Midnight town, all communication channels suddenly went dark. He’d laughed to himself thinking how frustrated Glimmer would have been about that. But maybe the game took care of sending her AI-generated messages simulating his presence. Despite the disturbing thought of having an AI generated clone of himself, he almost hoped for it (he’d probably signed the consent for this without realising), so that he wouldn’t have to do a tedious recap about all what she’d missed.

Once he arrived in the town, the adventure followed a predictable pattern. The clues were also rather simple to follow.

The townspeople are all frozen in time, stuck in their daily routines and unable to move on. Your mission is to find the missing piece of continuity, a small hourglass that will set time back in motion and allow the townspeople to move forward.

The clue to finding the hourglass lies within a discarded pocket watch that can be found in the mayor’s office. You must unscrew the back and retrieve a hidden key. The key will unlock a secret compartment in the town clock tower, where the hourglass is kept.

Be careful as you search for the hourglass, as the town is not as abandoned as it seems. Spectral figures roam the streets, and strange whispers can be heard in the wind. You may also encounter a mysterious old man who seems to know more about the town’s secrets than he lets on.

Evading the ghosts and spectres wasn’t too difficult once you got the hang of it. The old man however had been quite an elusive figure to find, but he was clearly the highlight of the whole adventure; he had been hiding in plain sight since the beginning of the adventure. One of the blue storks in the town that he’d thought had come with him through the portal was in actuality not a bird at all.

While he was focused on finishing the quest, the interaction with the hermit didn’t seem very helpful. Was he really from the game construct? When it was time to complete the quest and turn the hourglass to set the town back in motion, and resume continuity, some of his words came back to Xavier.

“The town isn’t what it seems. Recognise this precious moment where everything is still and you can realise it for the illusion that it is, a projection of your busy mind. When motion resumes, you will need to keep your mind quiet. The prize in the quest is not the completion of it, but the realisation you can stop the agitation at any moment, and return to what truly matters.”

The hermit had turned to him with clear dark eyes and asked “do you know what you are seeking in these adventures? do you know what truly matters to you?”

When he came out of the game, his quest completed, Xavier felt the words resonate ominously.

A buzz of the phone snapped him out of it.

It was a message from Zara. Apparently she’d found her way back to modernity.

[4:57] “Going to pick up Yasmin at the airport. You better sleep away the jetlag you lazy slugs, we have poultry damn plenty planned ahead – cackling bugger cooking lessons not looking forward to, but can be fun. Talk to you later. Z”

He had the impulse to go with her, but the lack of sleep was hitting back at him now, and he thought he’d better catch some so he could manage to realign with the timezone.

“The old man was right… that sounds like a lot of agitation coming our way…”

February 11, 2023 at 9:16 am #6536In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Youssef hadn’t changed a bit since they last met in real life. He definitely brought the bear in the bear hug he gave Xavier after Xavier had entered the soft sandal wood scented atmosphere of the Indian restaurant.

It was like there’d seen each other the day before, and conversation naturally flew without a thought on the few years’ hiatus between their last trip.

As they inquired about each other’s lives and events on the trip to get to Alice Springs, they ordered cheese nan, salted and mango lassi, a fish biryani and chicken tikka masala and a side thali for Youssef who was again ravenous after the jumpy ride. Soon after, the discussion turned to the road ahead.

“How long to the hostel?” asked Youssef, his mouth full of buns.

Xavier looked at his connected watch “It’s about 1 and half hour drive apparently. I called the number to check when to arrive, they told me to arrive before sunset… which I guess gives us 2-3 hours to visit around… I mean,” he looked at his friend “… we can also go straight there.”

Youssef nodded. He seemed to have had already enough of interactions in the past day.

Xavier continued “so it’s settled, we leave after we finish here. According to the landlady, it looks like Zara went off trekking, she didn’t seem too sure about Zara’s whereabouts. That would explain why we heard so little from her.”

Youssef laughed “If they don’t know Zara, I can bet they’ll be running around searching for her in the middle of the night.”

Xavier looked though the large window facing the street pensively. “I’m not sure I would want to get lost away from the beaten tracks here. There’s something so alien to the scale of it, and the dryness. Have you noticed we’re next to a river? I tried to have a look when I arrived, but it’s mostly dried up. And it’s supposed to be the wet season…”

Youssef didn’t reply, and turned to the leftovers of the biryani.

Despite the offering to top it off with gulab jamun and rose ice cream, it didn’t take too long to finish the healthy meal at the Indian restaurant. Youssef and Xavier went for the car.

“Here, catch!” Xavier threw the keys to Youssef. He knew his friend would have liked to drive; meanwhile he’d be able to catch on some emails and work stuff. After all, he was supposed to remote work for some days.

February 9, 2023 at 9:50 pm #6520In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Rajkumar had named his car JUMPY because he said it reminded him of his mother country. He drove like they were in the chaotic streets of an Indian city. Youssef’s fist was clenched on the door handle, his knuckles white. He needed to hold on to something just as much as he was afraid of loosing the door.

He had never been so happy as when Rajkumar stopped in front of his cousin’s shop and restaurant.

“Just in time for the best butter chicken in all Alice Springs!” said Rajkumar, pointing to the restaurant on the left.

“Just in time for the best butter chicken in all Alice Springs!” said Rajkumar, pointing to the restaurant on the left.Smells of greasy sauce, meat and spices floated in the air. Despite his legendary hunger, Youssef’s stomach started to protest from the recent treatment on the road. If he had had any doubt, he was sure now that he wouldn’t go on a trip in Jumpy with Rajkumar.

“Maybe I’ll go for the scarf first,” he said.

Rajkumar noded and pointed to the right, to a stout man squating in front of a pile of scarves.

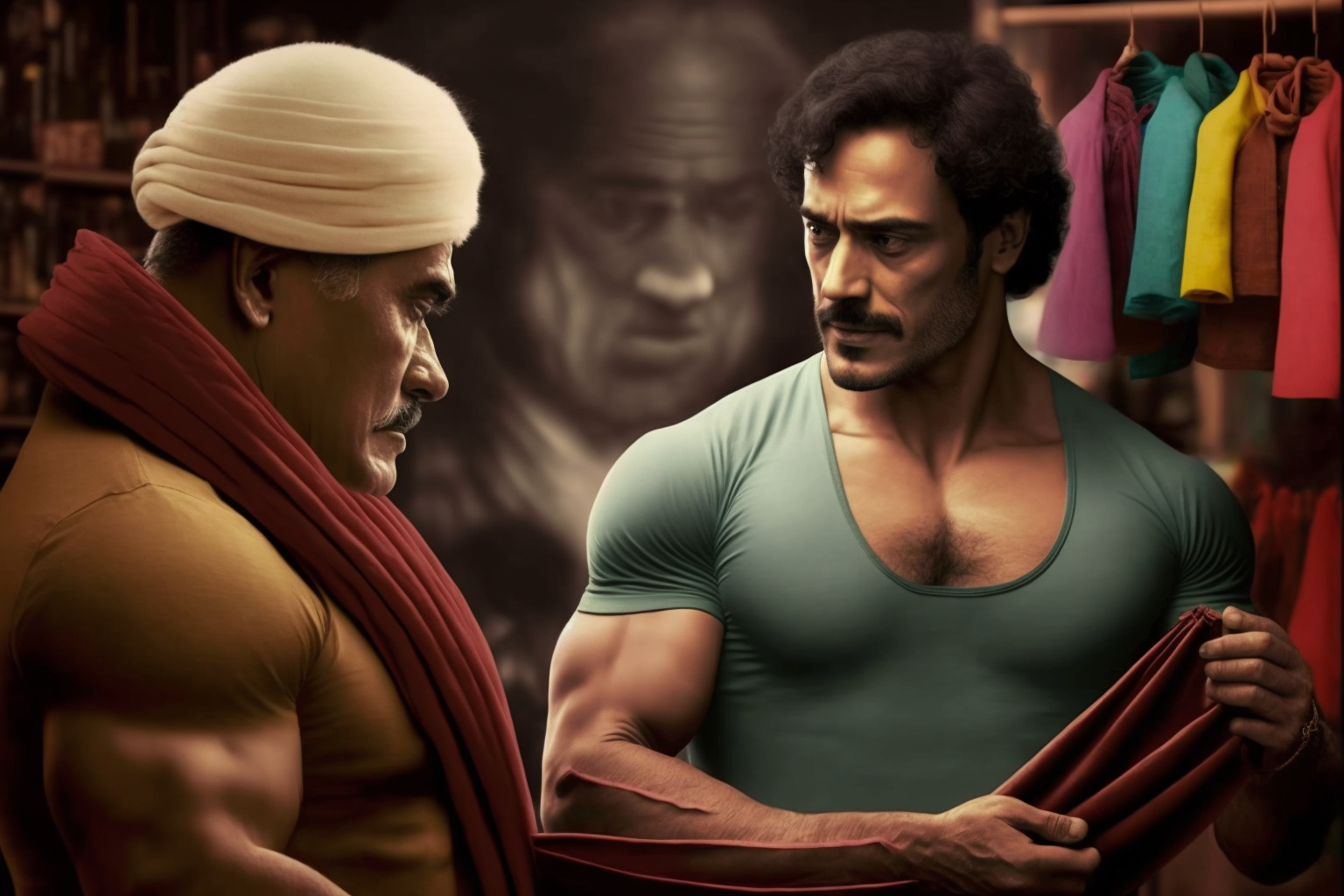

“This is cousin Ashish. You can’t find a better shop in town for scarves,” said Rajkumar. He high fived his cousin who looked like a giant in comparison with the short guide. They talked for a long time in what Youssef assumed to be some Indian dialect. At some point, his guide pointed a finger at him and said : “This big man is looking for a red scarf. I told him you had the best quality in town. Hand made, right from India. Ashish buys and sells the best to the best only. I have to go park the car and tell my other cousin to prepare you a meal. Best Indian food in Alice.”

After he left, cousin Ashish showed Youssef in. At the entrance incense burned at the feet of a couple of colourful Hindu gods. The intoxicating smell reminded him of a stop at a temple during his last trip with the documentary team. The face of Miss Tartiflate jumped into his mind. He would have to take care of THE BLOG at some point, but for now, he was looking for a red scarf. The inside of the shop was as messy as a Mongolian bazaar. Clothes upon clothes, and piles of scarves everywhere.

“Red scarves are over there, said Ashish. Follow me.”

He was less talkative than his cousin, which was a welcome relief. He led Youssef to the back of the shop. On the wall, the portrait in black and white of an old Indian man was watching over their shoulder.

Ashish took one long red scarf and put it around his neck.

“You can touch, he said. Very good quality. Very light. Like you wear nothing.”

Youssef took the end of the fabric in his hand. It felt very silky and light to the touch.

“That’s perfect, I’ll take it”, he said.

His phone buzzed in his pocket. He took it out and checked his messages.

- 📨

[Quirk Land] NEW QUEST OPENED

Looking at the time, it was already noon. Xavier must have landed in Alice already. He started to type a message to his friend :

💬

Meet me for lunch at Todd Mall. Patel indian restaurant next to fabric shopFebruary 9, 2023 at 7:59 pm #6518In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Xavier had been drowsing in the rental car for a while, waiting for a message from Youssef. He’d stopped the aircon despite the suffocating heat, as he was starting to feel cold. And he’d started to nose dive in dreaming.

The buzzing of his phone made him snap back to consciousness from the weirdest dream, he had to take a few seconds to adjust. The phone went into silent mode to voicemail before he got the chance to pick it up.

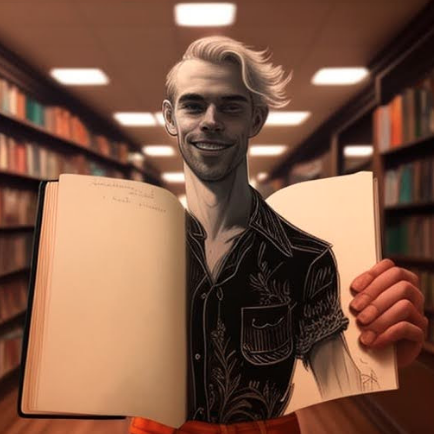

Weirdest dream ever. Few hours ago, he’d been going round and round the place, trying to find a library to buy a black book, but surprisingly, even when he’d managed to find a small bookstore, there were none to sell. None with a black cover…

He’d wondered —sometimes these quests are made to be difficult, but come on, how difficult could it be. Even a plain black-covered notebook would have been enough, but nothing!

That’s when he’d decided to drop the search, that he dozed off in the car.

Few images came back from the dream. First, the insane search, and books coming up in all shapes and forms, any color but black… or black but with black-and-white photos on the covers he didn’t want.

And then, there was one. He started to open it, and all the pages were blank. As he was browsing them, looking for a clue, like a pop-out book, something came up from the middle of the pages. And it was himself, smiling back at him. The shock snapped him right back to the rather quiet street of Alice Springs.

SOOO WEIIIIRD

He turned the ignition back on as well as the aircon. Checked his message.

- 📨

[Quirk Land] NEW QUEST OPENED - ➿

1 voicemail from ❣️🐝Brytta🐝❣️ - 💬 Youssef typing…

February 8, 2023 at 10:08 pm #6514In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Xavier offered the following quirk: “being the holder of continuity”

Quirk accepted.

Your quest takes place in the ghost town of Midnight, where time seems to have stood still. The townspeople are all frozen in time, stuck in their daily routines and unable to move on. Your mission is to find the missing piece of continuity, a small hourglass that will set time back in motion and allow the townspeople to move forward.

The clue to finding the hourglass lies within a discarded pocket watch that can be found in the mayor’s office. You must unscrew the back and retrieve a hidden key. The key will unlock a secret compartment in the town clock tower, where the hourglass is kept.

Be careful as you search for the hourglass, as the town is not as abandoned as it seems. Spectral figures roam the streets, and strange whispers can be heard in the wind. You may also encounter a mysterious old man who seems to know more about the town’s secrets than he lets on.

Proof of completion can be shown by taking a photo of the hourglass and the pocket watch, and sending it to the game’s creators.

Good luck!

February 7, 2023 at 10:43 pm #6512In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Zara offered the following quirk: “unleash my hidden rudeness”

Quirk accepted.

You find yourself in the bustling streets of an old medieval town. The people around you are going about their business, and you see vendors selling goods, street performers entertaining the crowd, and guards patrolling the area. You hear rumors about a secret society of mischievous tricksters who are known for causing trouble and making people’s lives more interesting.

You decide to investigate these rumors and join the society of tricksters, who call themselves the “Rude Ones.” You are tasked with finding the key to their hideout, a tile with a rude message written on it. To do this, you must complete several challenges and pranks around the town, each more mischievous than the last.

Your objective is to find the tile, sneak into the Rude Ones’ hideout, and cause as much chaos and trouble as possible. You must also find a way to insert a real-life prank or act of rudeness into your daily life, as proof of your success in the game.

Possible directions to investigate:

- Talk to the vendors and street performers to gather information about the Rude Ones.

- Observe the guards and see if they have any information on the secret society.

- Explore the different neighborhoods and see if anyone knows about the hideout.

Possible characters to engage:

- A mysterious street performer who is rumored to be part of the Rude Ones.

- A vendor who has a reputation for being rude to customers.

- A guard who is rumored to be in league with the Rude Ones.

Look for a tile with a rude message written on it, and capture proof of your real-life prank or act of rudeness. Good luck, and have fun!

January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

January 11, 2023 at 11:53 pm #6372

January 11, 2023 at 11:53 pm #6372In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

5 important keywords linked to Badul

- Action-space-time

- Harmonic fluid

- Rhythm

- Scale

- Choosing without limits.

Imagine four friends, Jib, Franci, Tracy, and Eric, who are all deeply connected through their shared passion for music and performance. They often spend hours together creating and experimenting with different sounds and rhythms.

One day, as they were playing together, they found that their combined energy had created a new essence, which they named Badul. This new essence was formed from the unique combination of their individual energies and personalities, and it quickly grew in autonomy and began to explore the world around it.

As Badul began to explore, it discovered that it had the ability to understand and create complex rhythms, and that it could use this ability to bring people together and help them find a sense of connection and purpose.

As Badul traveled, it would often come across individuals who were struggling to find their way in life. It would use its ability to create rhythm and connection to help these individuals understand themselves better and make the choices that were right for them.

In the scene, Badul is exploring a city, playing with the rhythms of the city, through the traffic, the steps of people, the ambiance. Badul would observe a person walking in the streets, head down, lost in thoughts. Badul would start playing a subtle tune, and as the person hears it, starts to walk with the rhythm, head up, starting to smile.

As the person continues to walk and follow the rhythm created by Badul, he begins to notice things he had never noticed before and begins to feel a sense of connection to the world around him. The music created by Badul serves as a guide, helping the person to understand himself and make the choices that will lead to a happier, more fulfilled life.

In this way, Badul’s focus is to bring people together, to connect them to themselves and to the world around them through the power of rhythm and music, and to be an ally in the search of personal revelation and understanding.

December 19, 2022 at 9:48 am #6352In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Birmingham Bootmaker

Samuel Jones 1816-1875

Samuel Jones the elder was born in Belfast circa 1779. He is one of just two direct ancestors found thus far born in Ireland. Samuel married Jane Elizabeth Brooker (born in St Giles, London) on the 25th January 1807 at St George, Hanover Square in London. Their first child Mary was born in 1808 in London, and then the family moved to Birmingham. Mary was my 3x great grandmother.

But this chapter is about her brother Samuel Jones. I noticed that on a number of other trees on the Ancestry site, Samuel Jones was a convict transported to Australia, but this didn’t tally with the records I’d found for Samuel in Birmingham. In fact another Samuel Jones born at the same time in the same place was transported, but his occupation was a baker. Our Samuel Jones was a bootmaker like his father.

Samuel was born on 28th January 1816 in Birmingham and baptised at St Phillips on the 19th August of that year, the fourth child and first son of Samuel the elder and Jane’s eleven children.

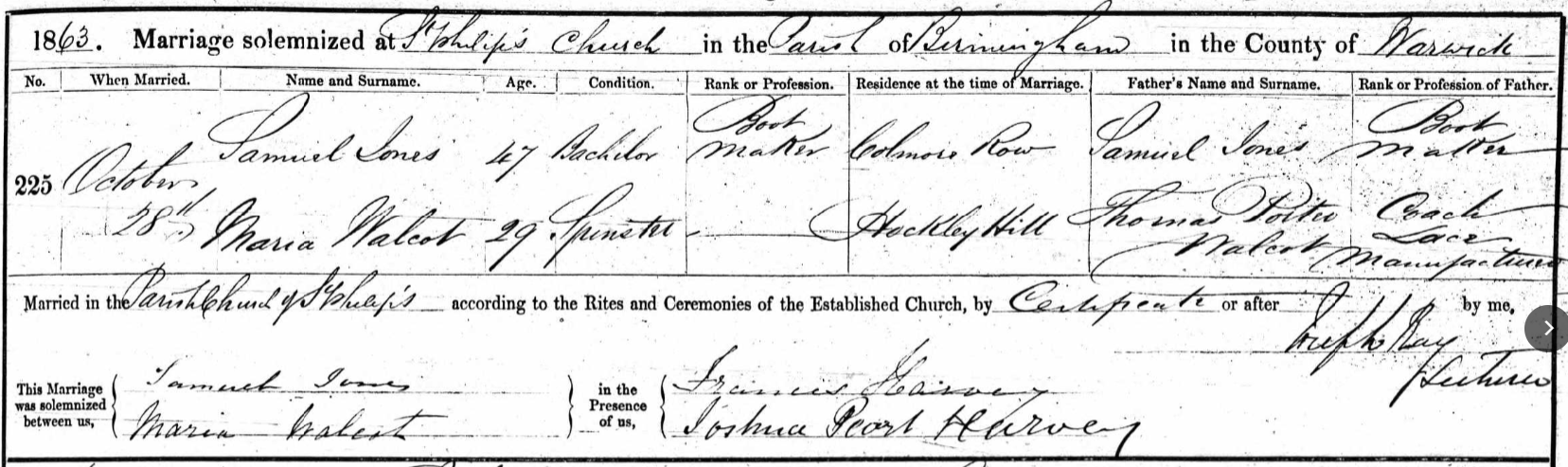

On the 1839 electoral register a Samuel Jones owned a property on Colmore Row, Birmingham.

Samuel Jones, bootmaker of 15, Colmore Row is listed in the 1849 Birmingham post office directory, and in the 1855 White’s Directory.

On the 1851 census, Samuel was an unmarried bootmaker employing sixteen men at 15, Colmore Row. A 9 year old nephew Henry Harris was living with him, and his mother Ruth Harris, as well as a female servant. Samuel’s sister Ruth was born in 1818 and married Henry Harris in 1840. Henry died in 1848.

Samuel was a 45 year old bootmaker at 15 Colmore Row on the 1861 census, living with Maria Walcot, a 26 year old domestic servant.

In October 1863 Samuel married Maria Walcot at St Philips in Birmingham. They don’t appear to have had any children as none appear on the 1871 census, where Samuel and Maria are living at the same address, with another female servant and two male lodgers by the name of Messant from Ipswich.

Marriage of Samuel Jones and Maria Walcot:

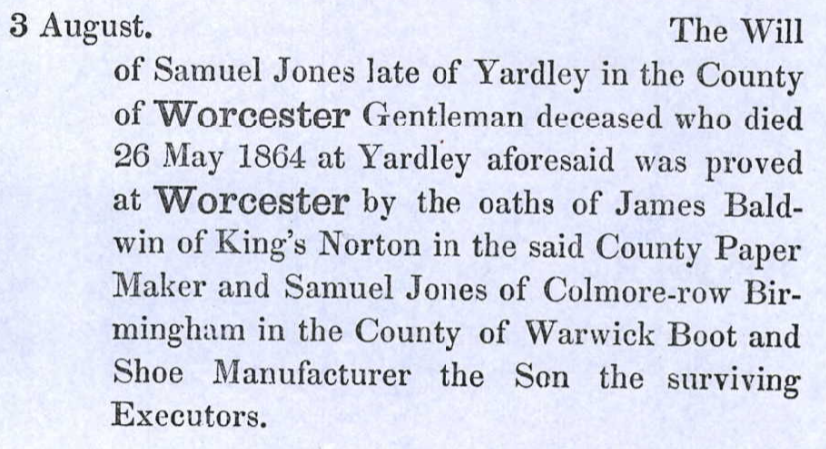

In 1864 Samuel’s father died. Samuel the son is mentioned in the probate records as one of the executors: “Samuel Jones of Colmore Row Birmingham in the county of Warwick boot and shoe manufacturer the son”.

Indeed it could hardly be clearer that this Samuel Jones was not the convict transported to Australia in 1834!

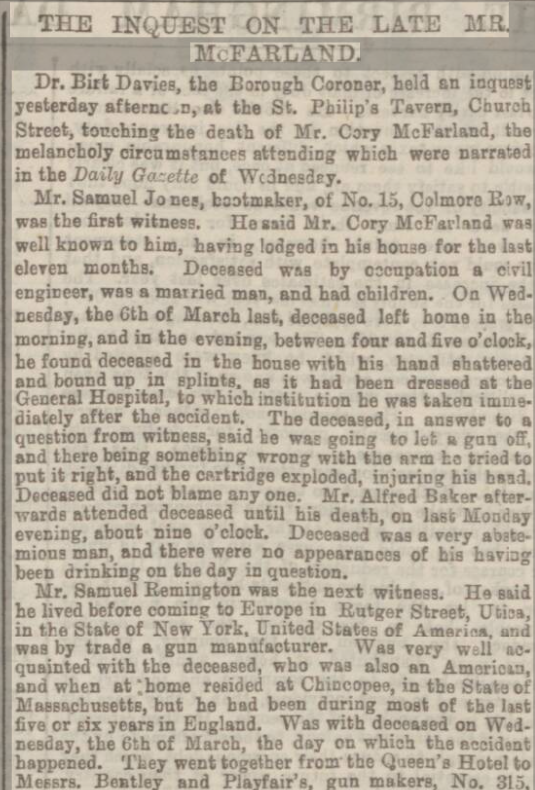

In 1867 Samuel Jones, bootmaker, was mentioned in the Birmingham Daily Gazette with regard to an unfortunate incident involving his American lodger, Cory McFarland. The verdict was accidental death.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Friday 05 April 1867:

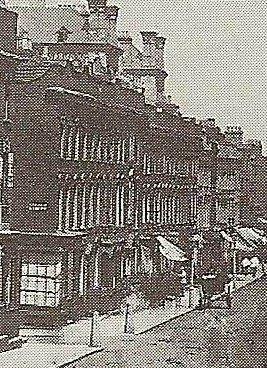

I asked a Birmingham history group for an old photo of Colmore Row. This photo is circa 1870 and number 15 is furthest from the camera. The businesses on the street at the time were as follows:

7 homeopathic chemist George John Morris. 8 surgeon dentist Frederick Sims. 9 Saul & Walter Samuel, Australian merchants. Surgeons occupied 10, pawnbroker John Aaron at 11 & 12. 15 boot & shoemaker. 17 auctioneer…

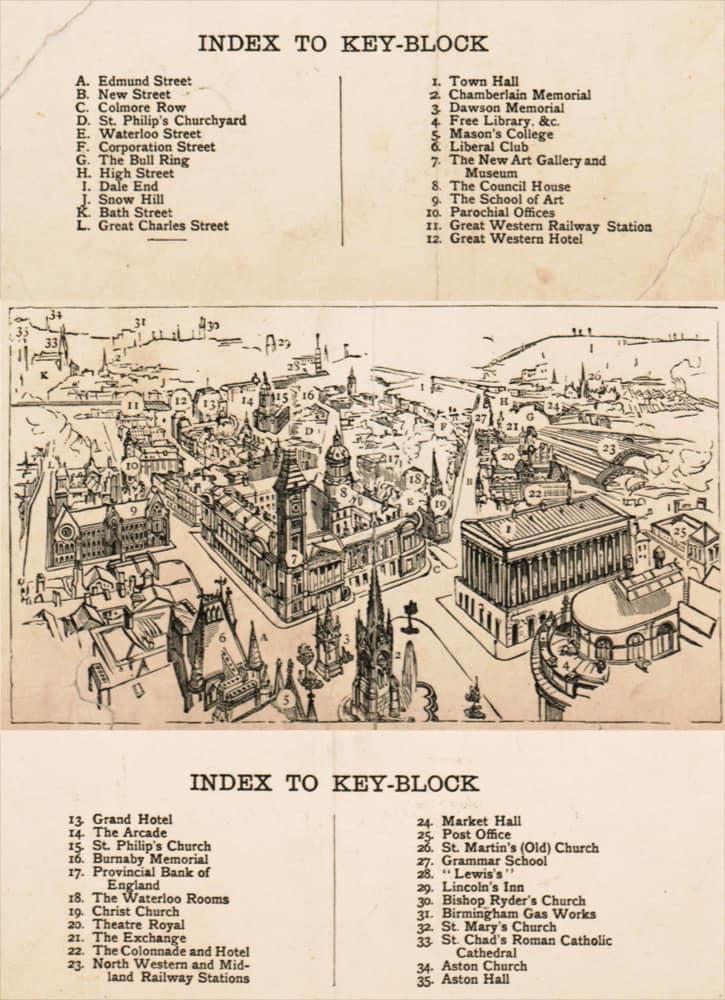

from Bird’s Eye View of Birmingham, 1886:

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

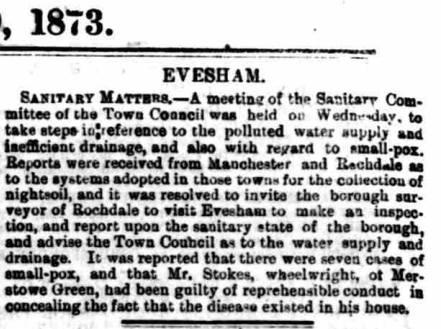

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

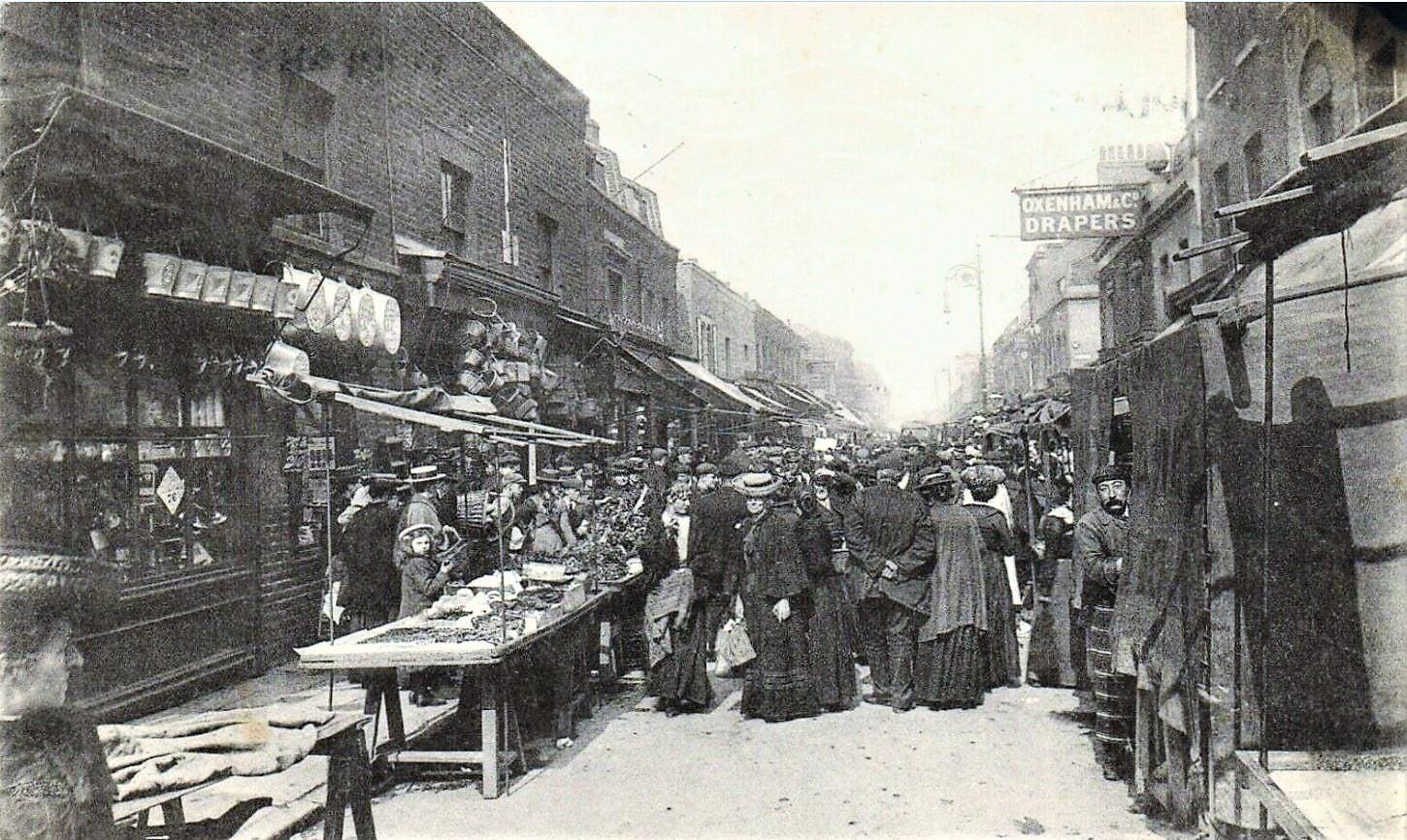

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

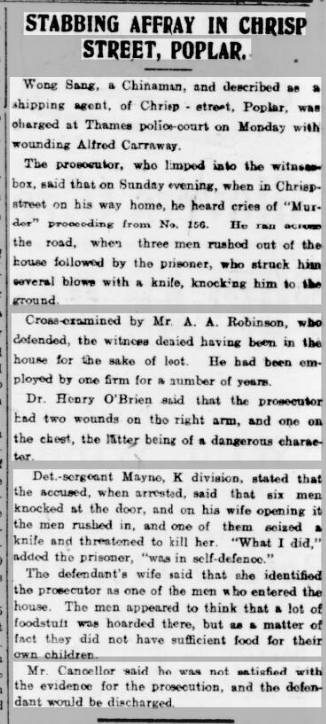

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

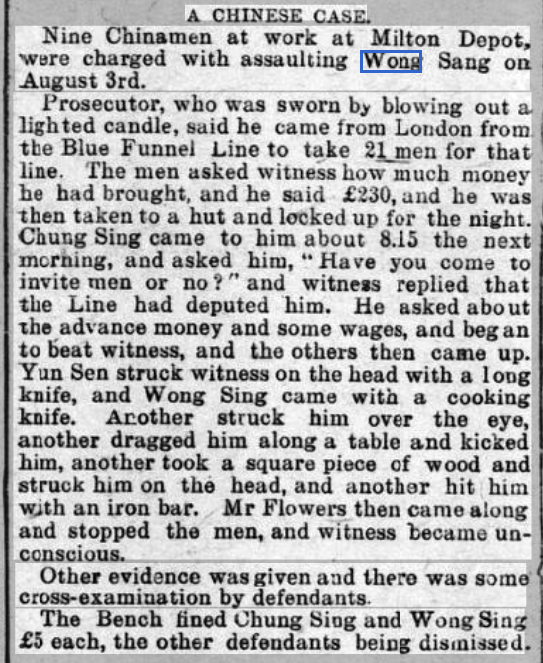

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

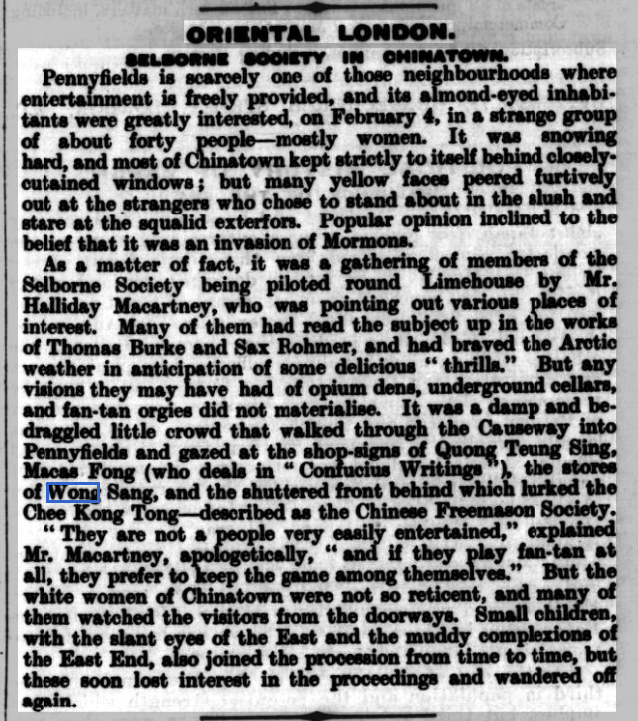

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

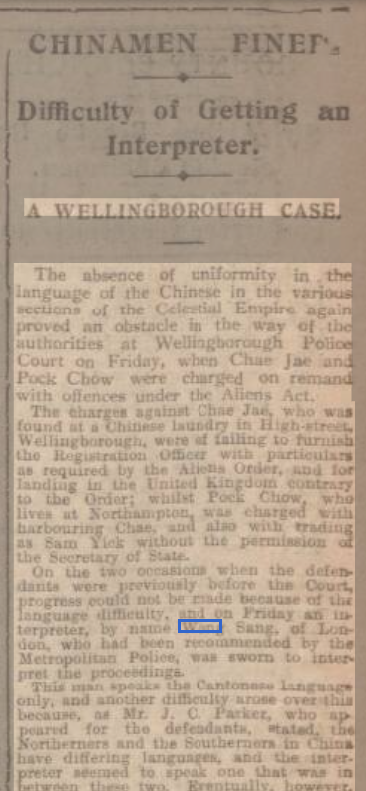

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

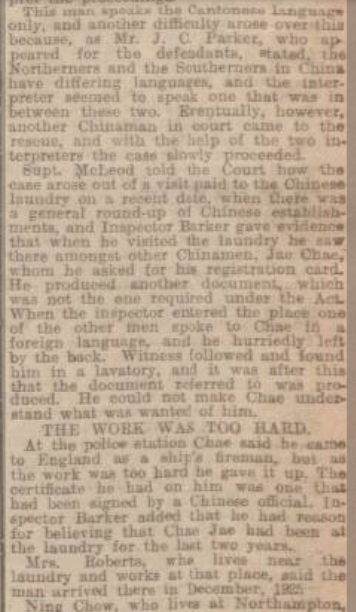

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wheelwrights of Broadway

Thomas Stokes 1816-1885

Frederick Stokes 1845-1917

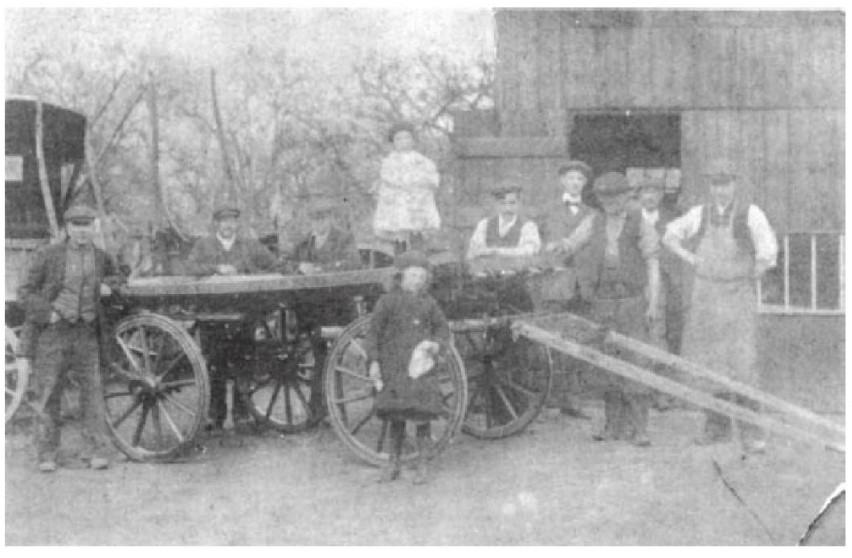

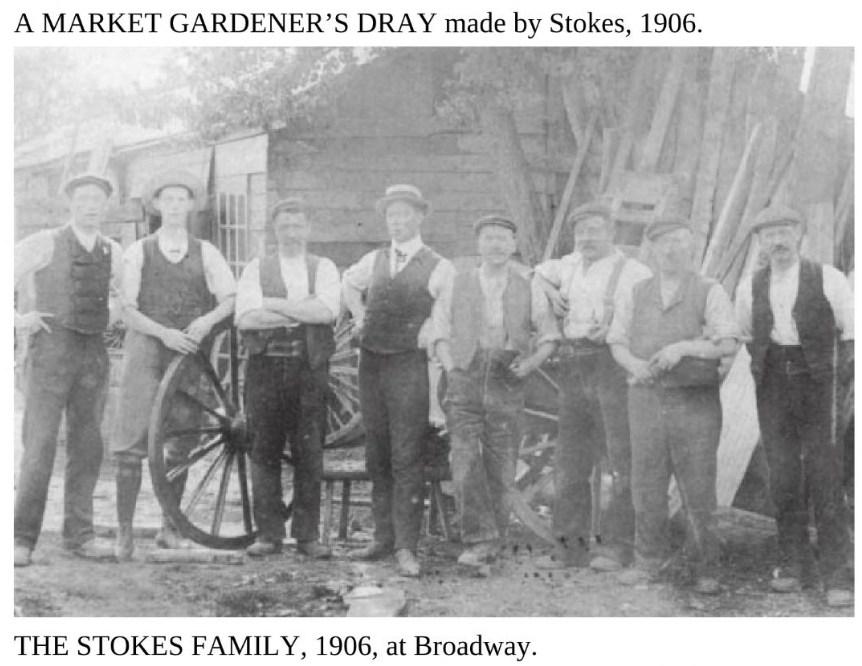

Stokes Wheelwrights. Fred on left of wheel, Thomas his father on right.

Thomas Stokes

Thomas Stokes was born in Bicester, Oxfordshire in 1816. He married Eliza Browning (born in 1814 in Tetbury, Gloucestershire) in Gloucester in 1840 Q3. Their first son William was baptised in Chipping Hill, Witham, Essex, on 3 Oct 1841. This seems a little unusual, and I can’t find Thomas and Eliza on the 1841 census. However both the 1851 and 1861 census state that William was indeed born in Essex.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza were living in Bledington, Gloucestershire, and Thomas was a journeyman carpenter.

Note that a journeyman does not mean someone who moved around a lot. A journeyman was a tradesman who had served his trade apprenticeship and mastered his craft, not bound to serve a master, but originally hired by the day. The name derives from the French for day – jour.

Also on the 1851 census: their daughter Susan, born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1844; son Frederick born in Bledington Gloucestershire in 1846; daughter Louisa born in Foxcote Oxfordshire in 1849; and 2 month old daughter Harriet born in Bledington in 1851.

On the 1861 census Thomas and Eliza were living in Evesham, Worcestershire, and daughter Susan was no longer living at home, but William, Fred, Louisa and Harriet were, as well as daughter Emily born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1856. Thomas was a wheelwright.

On the 1871 census Thomas and Eliza were still living in Evesham, and Thomas was a wheelwright employing three apprentices. Son Fred, also a wheelwright, and his wife Ann Rebecca live with them.

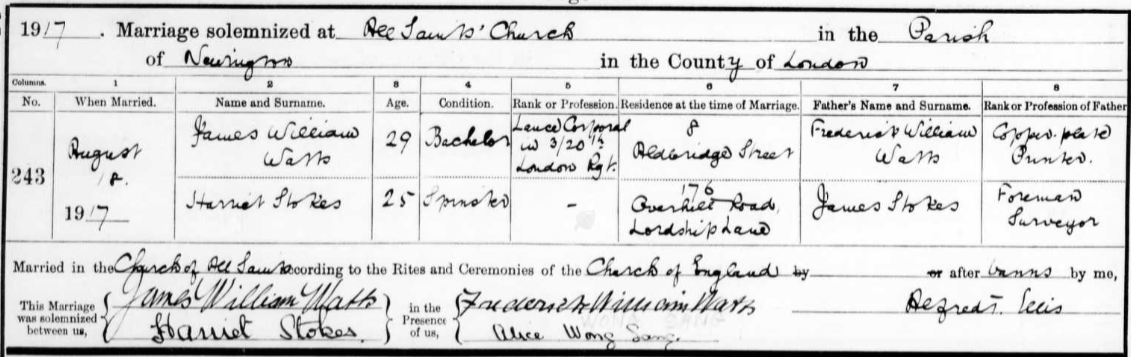

Mr Stokes, wheelwright, was found guilty of reprehensible conduct in concealing the fact that small-pox existed in his house, according to a mention in The Oxfordshire Weekly News on Wednesday 19 February 1873:

From Paul Weaver’s ancestry website:

“It was Thomas Stokes who built the first “Famous Vale of Evesham Light Gardening Dray for a Half-Legged Horse to Trot” (the quotation is from his account book), the forerunner of many that became so familiar a sight in the towns and villages from the 1860s onwards. He built many more for the use of the Vale gardeners.

Thomas also had long-standing business dealings with the people of the circus and fairgrounds, and had a contract to effect necessary repairs and renewals to their waggons whenever they visited the district. He built living waggons for many of the show people’s families as well as shooting galleries and other equipment peculiar to the trade of his wandering customers, and among the names figuring in his books are some still familiar today, such as Wilsons and Chipperfields.

He is also credited with inventing the wooden “Mushroom” which was used by housewives for many years to darn socks. He built and repaired all kinds of vehicles for the gentry as well as for the circus and fairground travellers.

Later he lived with his wife at Merstow Green, Evesham, in a house adjoining the Almonry.”

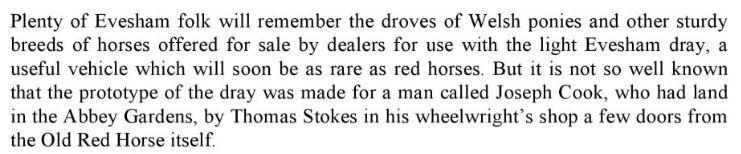

An excerpt from the book Evesham Inns and Signs by T.J.S. Baylis:

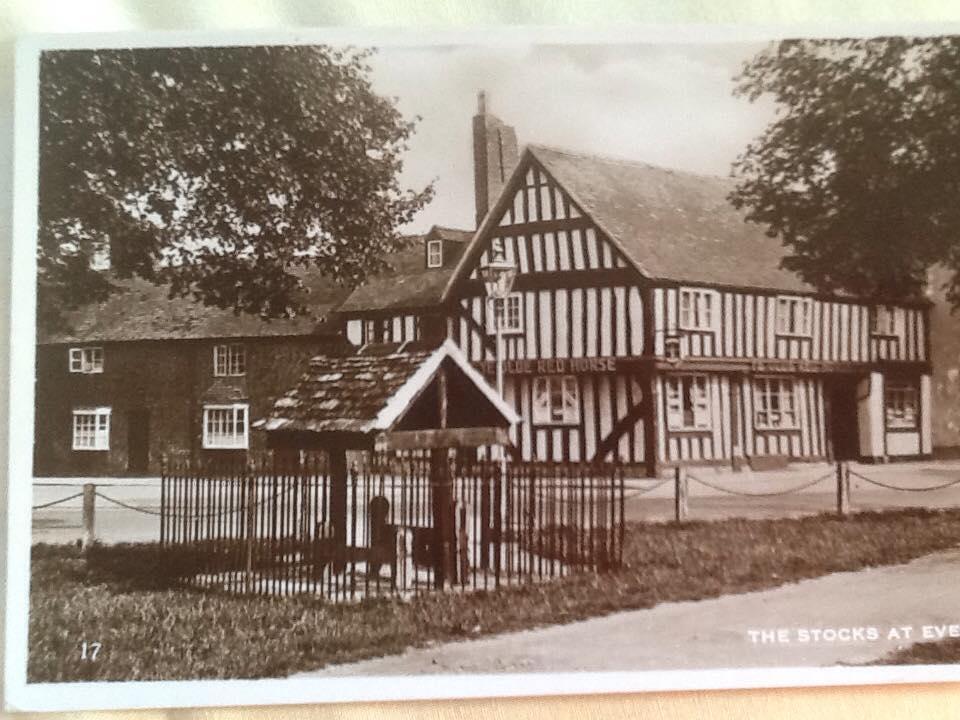

The Old Red Horse, Evesham:

Thomas died in 1885 aged 68 of paralysis, bronchitis and debility. His wife Eliza a year later in 1886.

Frederick Stokes

In Worcester in 1870 Fred married Ann Rebecca Day, who was born in Evesham in 1845.

Ann Rebecca Day:

In 1871 Fred was still living with his parents in Evesham, with his wife Ann Rebecca as well as their three month old daughter Annie Elizabeth. Fred and Ann (referred to as Rebecca) moved to La Quinta on Main Street, Broadway.

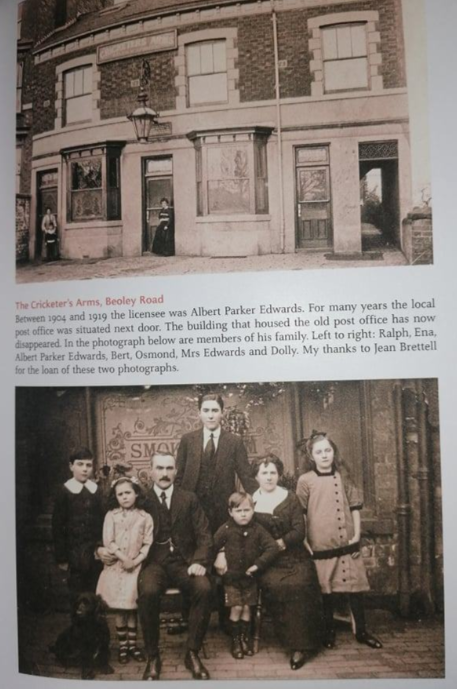

Rebecca Stokes in the doorway of La Quinta on Main Street Broadway, with her grandchildren Ralph and Dolly Edwards:

Fred was a wheelwright employing one man on the 1881 census. In 1891 they were still in Broadway, Fred’s occupation was wheelwright and coach painter, as well as his fifteen year old son Frederick.

In the Evesham Journal on Saturday 10 December 1892 it was reported that “Two cases of scarlet fever, the children of Mr. Stokes, wheelwright, Broadway, were certified by Mr. C. W. Morris to be isolated.”

Still in Broadway in 1901 and Fred’s son Albert was also a wheelwright. By 1911 Fred and Rebecca had only one son living at home in Broadway, Reginald, who was a coach painter. Fred was still a wheelwright aged 65.

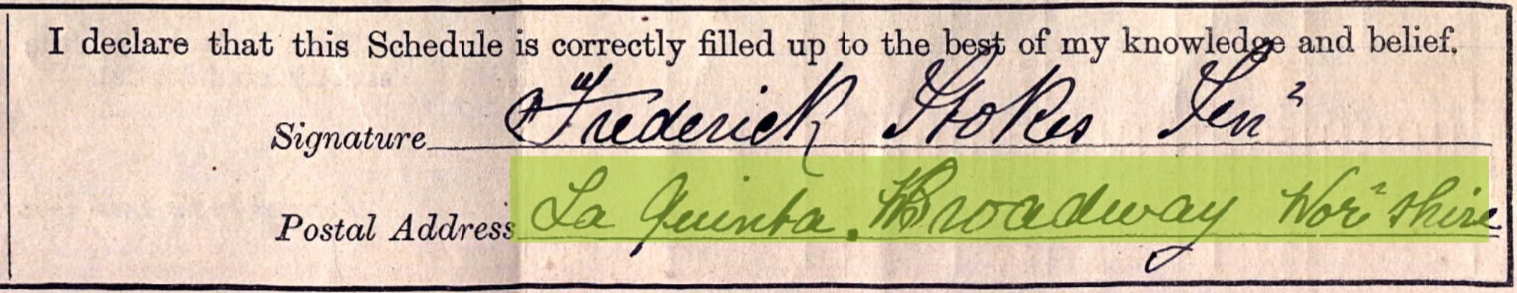

Fred’s signature on the 1911 census:

Rebecca died in 1912 and Fred in 1917.

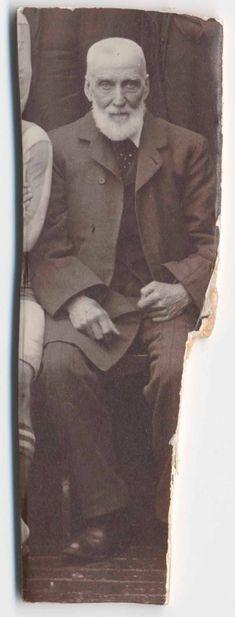

Fred Stokes:

In the book Evesham to Bredon From Old Photographs By Fred Archer:

October 21, 2022 at 2:06 pm #6337

October 21, 2022 at 2:06 pm #6337In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Annie Elizabeth Stokes

1871-1961

“Grandma E”

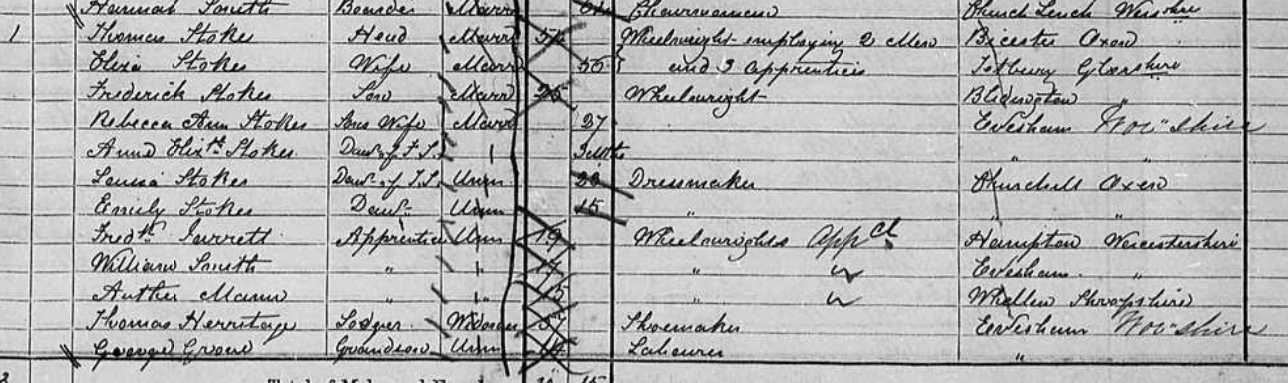

Annie, my great grandmother, was born 2 Jan 1871 in Merstow Green, Evesham, Worcestershire. Her father Fred Stokes was a wheelwright. On the 1771 census in Merston Green Annie was 3 months old and there was quite a houseful: Annies parents Fred and Rebecca, Fred’s parents Thomas and Eliza and two of their daughters, three apprentices, a lodger and one of Thomas’s grandsons.

1771 census Merstow Green, Evesham:

Annie at school in the early 1870s in Broadway. Annie is in the front on the left and her brother Fred is in the centre of the first seated row:

In 1881 Annie was a 10 year old visitor at the Angel Inn, Chipping Camden. A boarder there was 19 year old William Halford, a wheelwright apprentice. John Such, a 62 year old widower, was the innkeeper. Her parents and two siblings were living at La Quinta, on Main Street in Broadway.

According to her obituary in 1962, “When the Maxton family visited Broadway to stay with Mr and Madame de Navarro at Court Farm, they offered Annie a family post with them which took her for several years to Paris and other parts of the continent.”

Mary Anderson was an American theatre actress. In 1890 she married Antonio Fernando de Navarro. She became known as Mary Anderson de Navarro. They settled at Court Farm in the Cotswolds, Broadway, Worcestershire, where she cultivated an interest in music and became a noted hostess with a distinguished circle of musical, literary and ecclesiastical guests. As in the years when Mary lived there, it was often filled with visiting artists and musicians, including Myra Hess and a young Jacqueline du Pré. (via Wikipedia)

Court Farm, Broadway:

Annie was an assistant to a tobacconist in West Bromwich in 1991, living as a boarder with William Calcutt and family. He future husband Albert was living in neighbouring Tipton in 1891, working at a pawnbroker apprenticeship.

Annie married Albert Parker Edwards in 1898 in Evesham. On the 1901 census, she was in hospital in Redditch.

By 1911, Anne and Albert had five children and were living at the Cricketers Arms in Redditch.

Behind the bar in 1904 shortly after taking over at the Cricketers Arms. From a book on Redditch pubs:

Annie was referred to in later years as Grandma E, probably to differentiate between her and my fathers Grandma T, as both lived to a great age.

Annie with her grandson Reg on the left and her daughter in law Peggy on the right, in the early 1950s:

Annie at my christening in 1959:

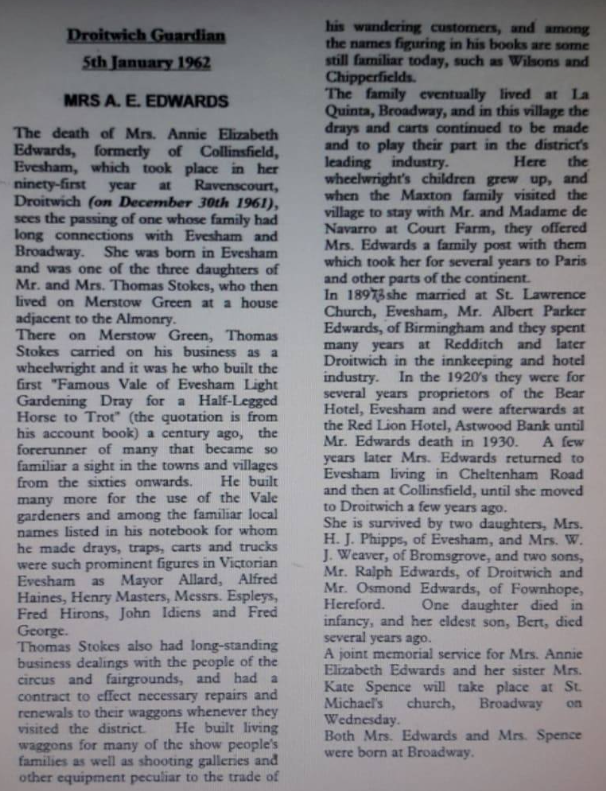

Annie died 30 Dec 1961, aged 90, at Ravenscourt nursing home, Redditch. Her obituary in the Droitwich Guardian in January 1962:

Note that this obituary contains an obvious error: Annie’s father was Frederick Stokes, and Thomas was his father.

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

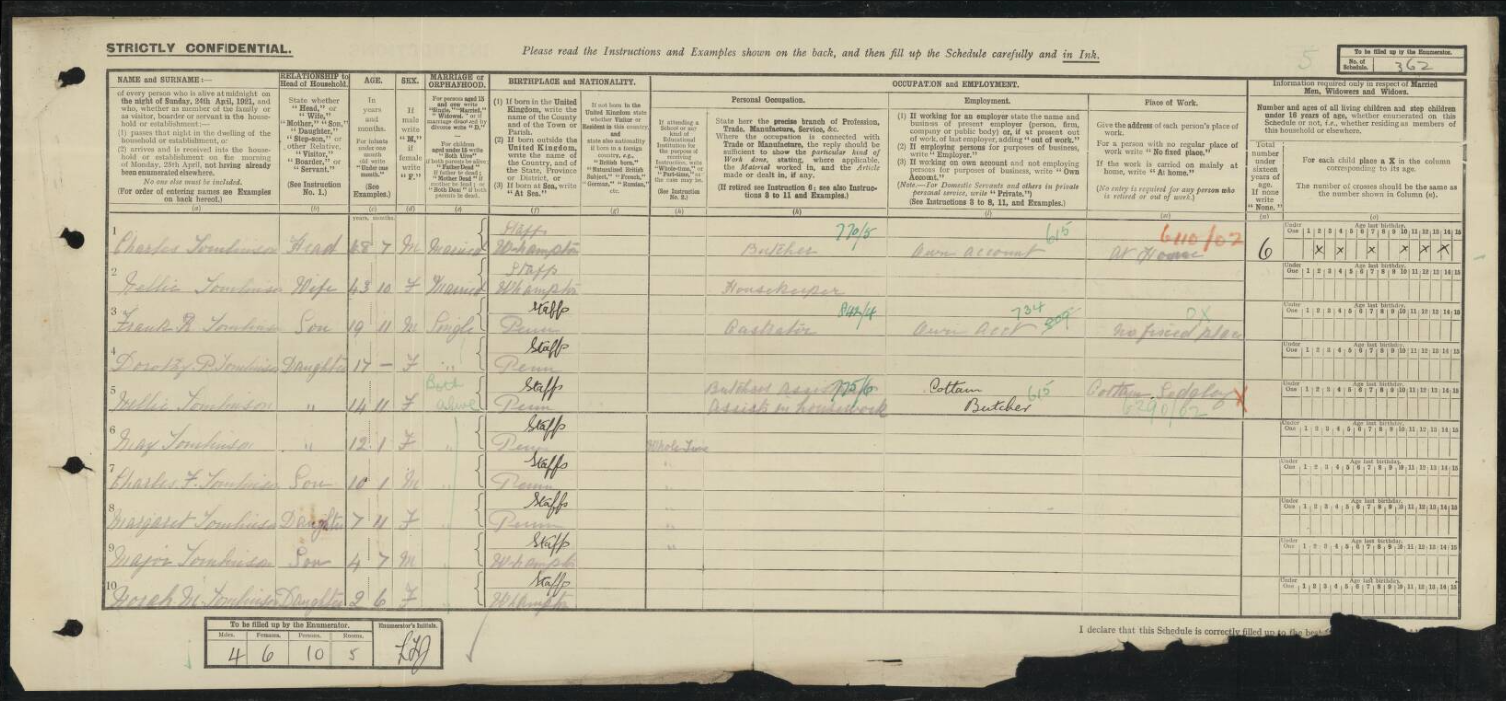

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

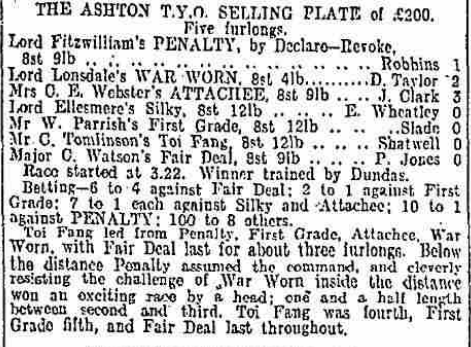

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

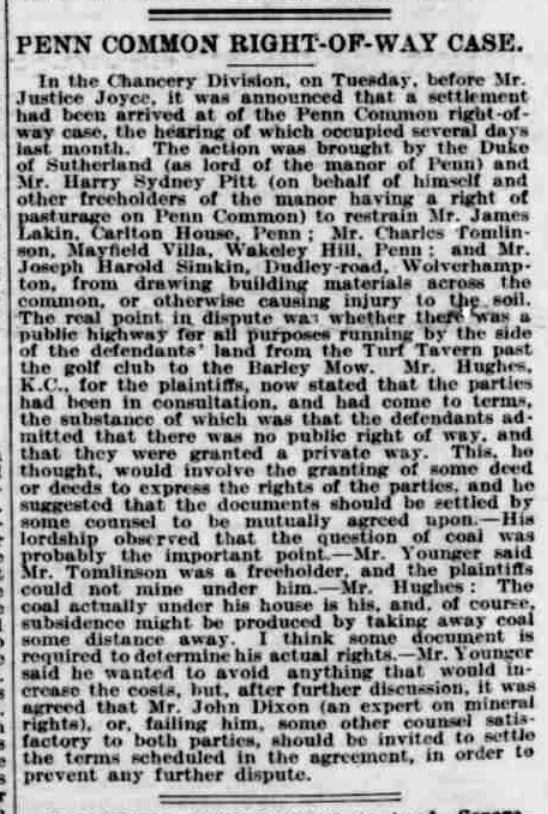

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

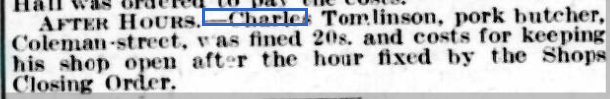

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

September 21, 2022 at 1:25 pm #6331In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

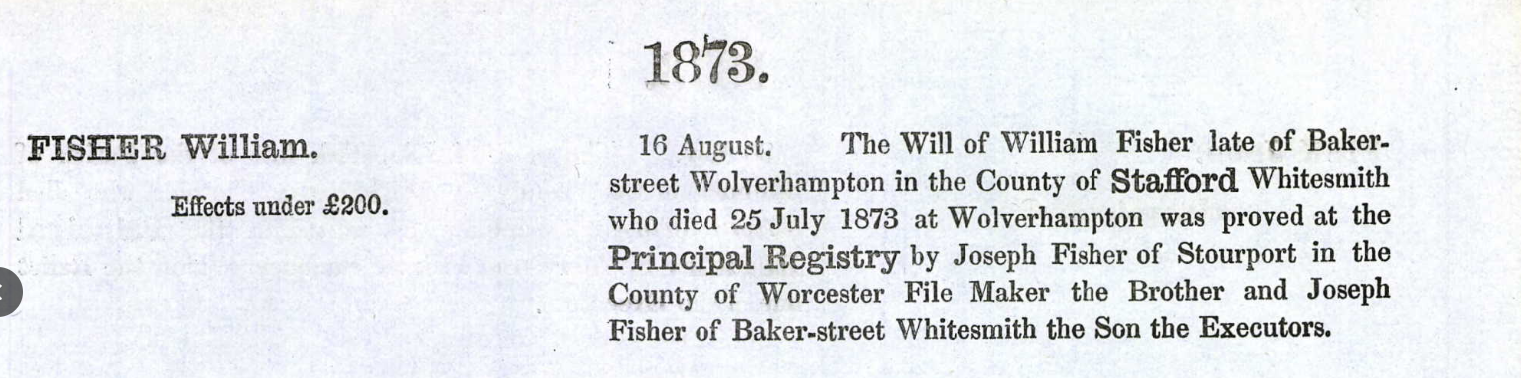

Whitesmiths of Baker Street

The Fishers of Wolverhampton

My fathers mother was Margaret Tomlinson born in 1913, the youngest but one daughter of Charles Tomlinson and Nellie Fisher of Wolverhampton.

Nellie Fisher was born in 1877. Her parents were William Fisher and Mary Ann Smith.

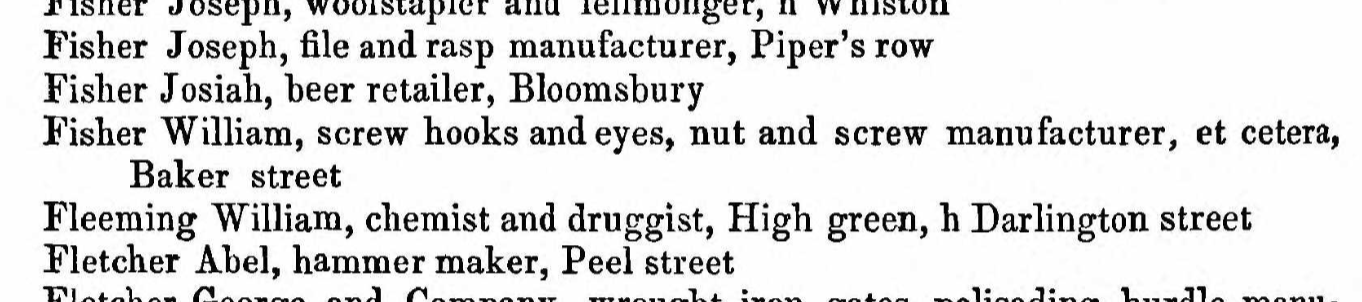

William Fisher born in 1834 was a whitesmith on Baker St on the 1881 census; Nellie was 3 years old. Nellie was his youngest daughter.

William was a whitesmith (or screw maker) on all of the censuses but in 1901 whitesmith was written for occupation, then crossed out and publican written on top. This was on Duke St, so I searched for William Fisher licensee on longpull black country pubs website and he was licensee of The Old Miners Arms on Duke St in 1896. The pub closed in 1906 and no longer exists. He was 67 in 1901 and just he and wife Mary Ann were at that address.

In 1911 he was a widower living alone in Upper Penn. Nellie and Charles Tomlinson were also living in Upper Penn on the 1911 census, and my grandmother was born there in 1913.

William’s father William Fisher born in 1792, Nellie’s grandfather, was a whitesmith on Baker St on the 1861 census employing 4 boys, 2 men, 3 girls. He died in 1873.

William Fisher the elder appears in a number of directories including this one:

1851 Melville & Co´s Directory of Wolverhampton

I noticed that all the other ancestry trees (as did my fathers cousin on the Tomlinson side) had MARY LUNN from Birmingham in Warwickshire marrying William Fisher the elder in 1828. But on ALL of the censuses, Mary’s place of birth was Staffordshire, and on one it said Bilston. I found another William Fisher and Mary marriage in Sedgley in 1829, MARY PITT.

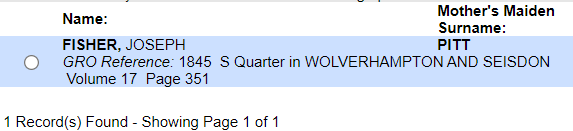

You can order a birth certificate from the records office with mothers maiden name on, but only after 1837. So I looked for Williams younger brother Joseph, born 1845. His mothers maiden name was Pitt. July 12, 2022 at 2:00 am #6318

July 12, 2022 at 2:00 am #6318In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“You’d better sit down,” said Olga gesturing to the end of her bed. As a rule, she did not have visitors so she saw no need to clutter up the available space in her tiny room with an extra chair. A large proportion of her life was spent in her armchair and she was content that way. While Egbert perched on the end of the bed, she lowered herself into the soft and familiar confines of her armchair and felt instantly soothed. It was true, sometimes she felt a tinge of regret when she considered how disappointed her younger self would be to see her now. But she hadn’t lived through what I’ve lived through so she can mind her own damn business,” she thought.

“It is just a story, twisted in the telling I expect.” Olga knew her voice held no conviction.

Egbert opened his mouth as though to speak. Closed it again.

“You look like a fish,” said Olga folding her arms.

“They say you and the Mayor go back a long way. Are you telling me that is not true?

“And what if we do?”

“You know he is Ursula’s uncle and a very powerful man. They say even the great president Voldomeer Zumbaskee holds him in great regard. They say …”

“Pfft! They say!” snapped Olga. “Who are these chattering fools you listen to, Egbert Gofindlevsky? I’d rather end up on the streets than ask a favour from that mountebank.”

Egbert jumped up from the bed and shook a fist at her. “And end up on the streets you will, Olga Herringbonevsky, along with the rest of us. You really want that on your conscience?”

July 6, 2022 at 11:41 am #6313In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Egbert Gofindlevsky rapped on the door of room number 22. The letter flapped against his pin striped trouser leg as his hand shook uncontrollably, his habitual tremor exacerbated with the shock. Remembering that Obadiah Sproutwinklov was deaf, he banged loudly on the door with the flat of his hand. Eventually the door creaked open.

Egbert flapped the letter in from of Obadiah’s face. “Have you had one of these?” he asked.

“If you’d stop flapping it about I might be able to see what it is,” Obadiah replied. “Oh that! As a matter of fact I’ve had one just like it. The devils work, I tell you! A practical joke, and in very poor taste!”

Egbert was starting to wish he’d gone to see Olga Herringbonevsky first. “Can I come in?” he hissed, “So we can discuss it in private?”

Reluctantly Obadiah pulled the door open and ushered him inside the room. Egbert looked around for a place to sit, but upon noticing a distinct odour of urine decided to remain standing.

“Ursula is booting us out, where are we to go?”

“Eh?” replied Obadiah, cupping his ear. “Speak up, man!”

Egbert repeated his question.

“No need to shout!”

The two old men endeavoured to conduct a conversation on this unexepected turn of events, the upshot being that Obadiah had no intention of leaving his room at all henceforth, come what may, and would happily starve to death in his room rather than take to the streets.

Egbert considered this form of action unhelpful, as he himself had no wish to starve to death in his room, so he removed himself from room 22 with a disgruntled sigh and made his way to Olga’s room on the third floor.

March 21, 2022 at 7:05 am #6284In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

To Australia

Grettons

Charles Herbert Gretton 1876-1954

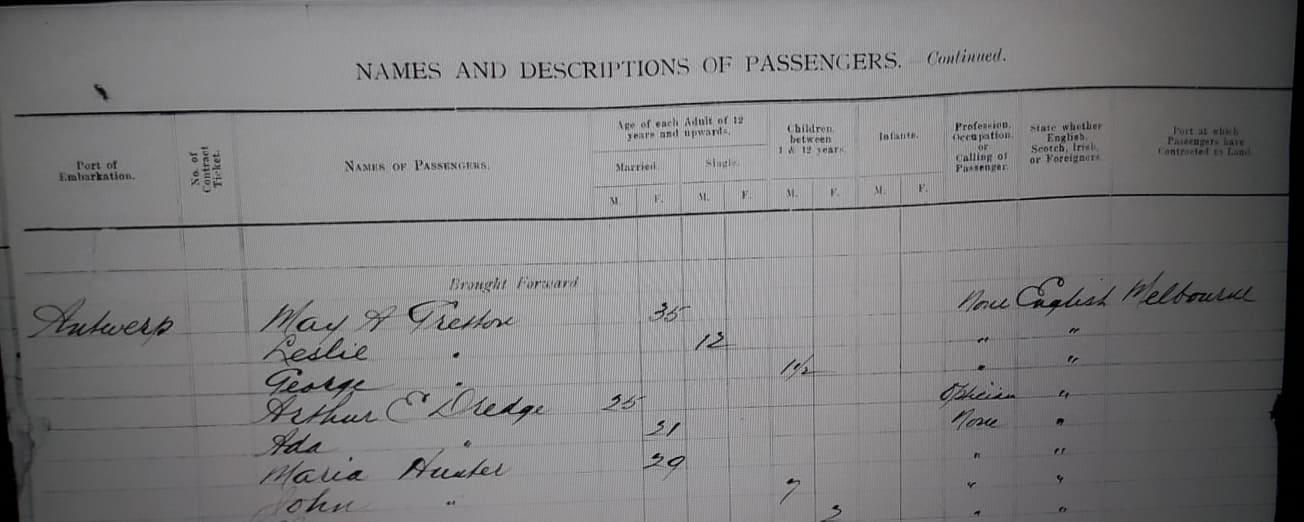

Charles Gretton, my great grandmothers youngest brother, arrived in Sydney Australia on 12 February 1912, having set sail on 5 January 1912 from London. His occupation on the passenger list was stockman, and he was traveling alone. Later that year, in October, his wife and two sons sailed out to join him.

Charles was born in Swadlincote. He married Mary Anne Illsley, a local girl from nearby Church Gresley, in 1898. Their first son, Leslie Charles Bloemfontein Gretton, was born in 1900 in Church Gresley, and their second son, George Herbert Gretton, was born in 1910 in Swadlincote. In 1901 Charles was a colliery worker, and on the 1911 census, his occupation was a sanitary ware packer.

Charles and Mary Anne had two more sons, both born in Footscray: Frank Orgill Gretton in 1914, and Arthur Ernest Gretton in 1920.

On the Australian 1914 electoral rolls, Charles and Mary Ann were living at 72 Moreland Street, Footscray, and in 1919 at 134 Cowper Street, Footscray, and Charles was a labourer. In 1924, Charles was a sub foreman, living at 3, Ryan Street E, Footscray, Australia. On a later electoral register, Charles was a foreman. Footscray is a suburb of Melbourne, and developed into an industrial zone in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Charles died in Victoria in 1954 at the age of 77. His wife Mary Ann died in 1958.

Charles and Mary Ann Gretton:

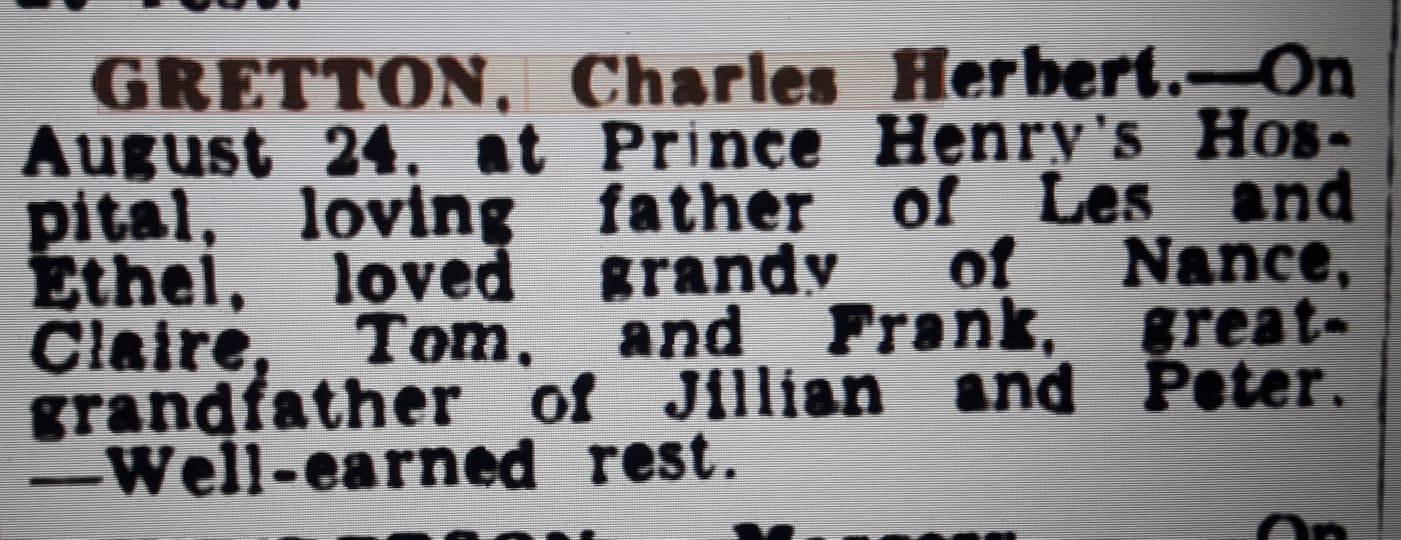

Leslie Charles Bloemfontein Gretton 1900-1955

Leslie was an electrician. He married Ethel Christine Halliday, born in 1900 in Footscray, in 1927. They had four children: Tom, Claire, Nancy and Frank. By 1943 they were living in Yallourn. Yallourn, Victoria was a company town in Victoria, Australia built between the 1920s and 1950s to house employees of the State Electricity Commission of Victoria, who operated the nearby Yallourn Power Station complex. However, expansion of the adjacent open-cut brown coal mine led to the closure and removal of the town in the 1980s.

On the 1954 electoral registers, daughter Claire Elizabeth Gretton, occupation teacher, was living at the same address as Leslie and Ethel.

Leslie died in Yallourn in 1955, and Ethel nine years later in 1964, also in Yallourn.

George Herbert Gretton 1910-1970

George married Florence May Hall in 1934 in Victoria, Australia. In 1942 George was listed on the electoral roll as a grocer, likewise in 1949. In 1963 his occupation was a process worker, and in 1968 in Flinders, a horticultural advisor.

George died in Lang Lang, not far from Melbourne, in 1970.

Frank Orgill Gretton 1914-

Arthur Ernest Gretton 1920-

Orgills

John Orgill 1835-1911

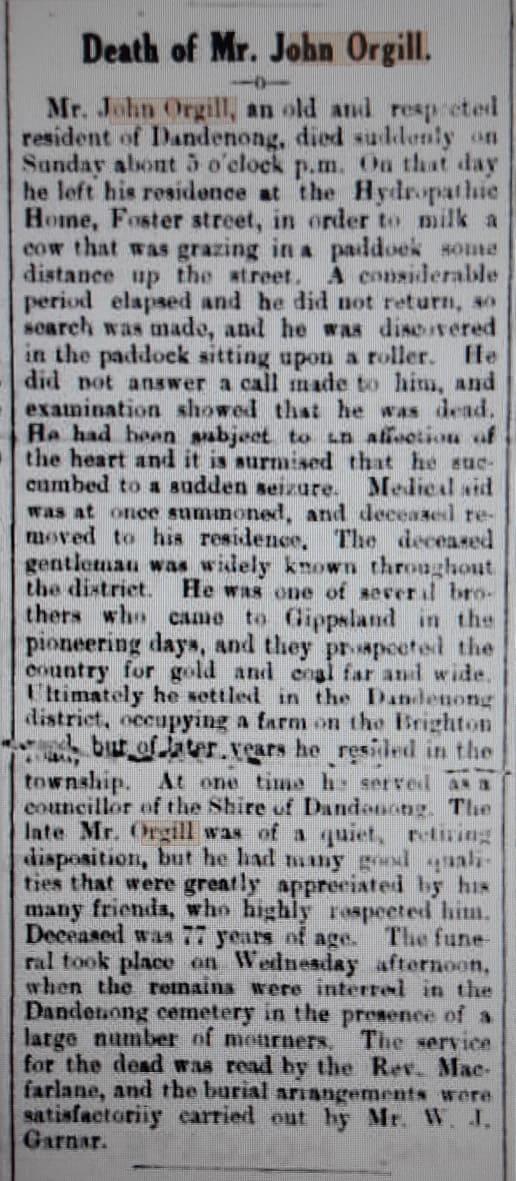

John Orgill was Charles Herbert Gretton’s uncle. He emigrated to Australia in 1865, and married Elizabeth Mary Gladstone 1845-1926 in Victoria in 1870. Their first child was born in December that year, in Dandenong. They had seven children, and their three sons all have the middle name Gladstone.

John Orgill was a councillor for the Shire of Dandenong in 1873, and between 1876 and 1879.

John Orgill:

John Orgill obituary in the South Bourke and Mornington Journal, 21 December 1911:

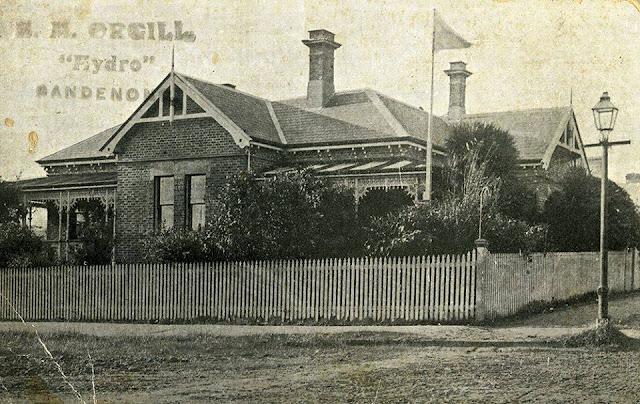

John’s wife Elizabeth Orgill, a teacher and a “a public spirited lady” according to newspaper articles, opened a hydropathic hospital in Dandenong called Gladstone House.

Elizabeth Gladstone Orgill:

On the Old Dandenong website:

Gladstone House hydropathic hospital on the corner of Langhorne and Foster streets (153 Foster Street) Dandenong opened in 1896, working on the theory of water therapy, no medicine or operations. Her husband passed away in 1911 at 77, around similar time Dr Barclay Thompson obtained control of the practice. Mrs Orgill remaining on in some capacity.

Elizabeth Mary Orgill (nee Gladstone) operated Gladstone House until at least 1911, along with another hydropathic hospital (Birthwood) on Cheltenham road. She was the daughter of William Gladstone (Nephew of William Ewart Gladstone, UK prime minister in 1874).

Around 1912 Dr A. E. Taylor took over the location from Dr. Barclay Thompson. Mrs Orgill was still working here but no longer controlled the practice, having given it up to Barclay. Taylor served as medical officer for the Shire for before his death in 1939. After Taylor’s death Dr. T. C. Reeves bought his practice in 1939, later that year being appointed medical officer,

Gladstone Road in Dandenong is named after her family, who owned and occupied a farming paddock in the area on former Police Paddock ground, the Police reserve having earlier been reduced back to Stud Road.

Hydropathy (now known as Hydrotherapy) and also called water cure, is a part of medicine and alternative medicine, in particular of naturopathy, occupational therapy and physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and treatment.

Gladstone House, Dandenong:

John’s brother Robert Orgill 1830-1915 also emigrated to Australia. I met (online) his great great grand daughter Lidya Orgill via the Old Dandenong facebook group.

John’s other brother Thomas Orgill 1833-1908 also emigrated to the same part of Australia.

Thomas Orgill:

One of Thomas Orgills sons was George Albert Orgill 1880-1949:

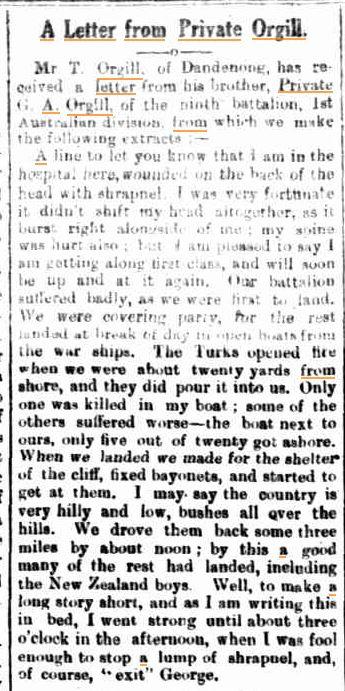

A letter was published in The South Bourke & Mornington Journal (Richmond, Victoria, Australia) on 17 Jun 1915, to Tom Orgill, Emerald Hill (South Melbourne) from hospital by his brother George Albert Orgill (4th Pioneers) describing landing of Covering Party prior to dawn invasion of Gallipoli:

Another brother Henry Orgill 1837-1916 was born in Measham and died in Dandenong, Australia. Henry was a bricklayer living in Measham on the 1861 census. Also living with his widowed mother Elizabeth at that address was his sister Sarah and her husband Richard Gretton, the baker (my great great grandparents). In October of that year he sailed to Melbourne. His occupation was bricklayer on his death records in 1916.

Two of Henry’s sons, Arthur Garfield Orgill born 1888 and Ernest Alfred Orgill born 1880 were killed in action in 1917 and buried in Nord-Pas-de-Calais, France. Another son, Frederick Stanley Orgill, died in 1897 at the age of seven.

A fifth brother, William Orgill 1842- sailed from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1861, at 19 years of age. Four years later in 1865 he sailed from Victoria, Australia to New Zealand.

I assumed I had found all of the Orgill brothers who went to Australia, and resumed research on the Orgills in Measham, in England. A search in the British Newspaper Archives for Orgills in Measham revealed yet another Orgill brother who had gone to Australia.

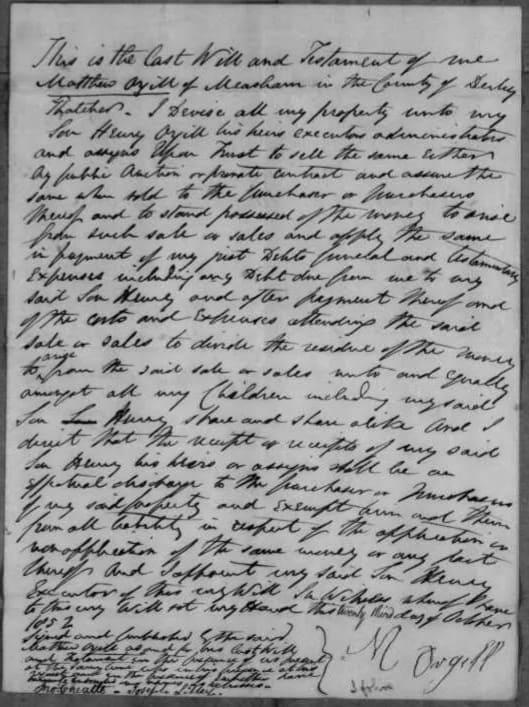

Matthew Orgill 1828-1907 went to South Africa and to Australia, but returned to Measham.

The Orgill brothers had two sisters. One was my great great great grandmother Sarah, and the other was Hannah. Hannah married Francis Hart in Measham. One of her sons, John Orgill Hart 1862-1909, was born in Measham. On the 1881 census he was a 19 year old carpenters apprentice. Two years later in 1883 he was listed as a joiner on the passenger list of the ship Illawarra, bound for Australia. His occupation at the time of his death in Dandenong in 1909 was contractor.

An additional coincidental note about Dandenong: my step daughter Emily’s Australian partner is from Dandenong.

Housleys

Charles Housley 1823-1856

Charles Housley emigrated to Australia in 1851, the same year that his brother George emigrated to USA. Charles is mentioned in the Narrative on the Letters by Barbara Housley, and appears in the Housley Letters chapters.

Rushbys

George “Mike” Rushby 1933-

Mike moved to Australia from South Africa. His story is a separate chapter.

March 10, 2022 at 7:40 am #6281In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Measham Thatchers

Orgills, Finches and Wards

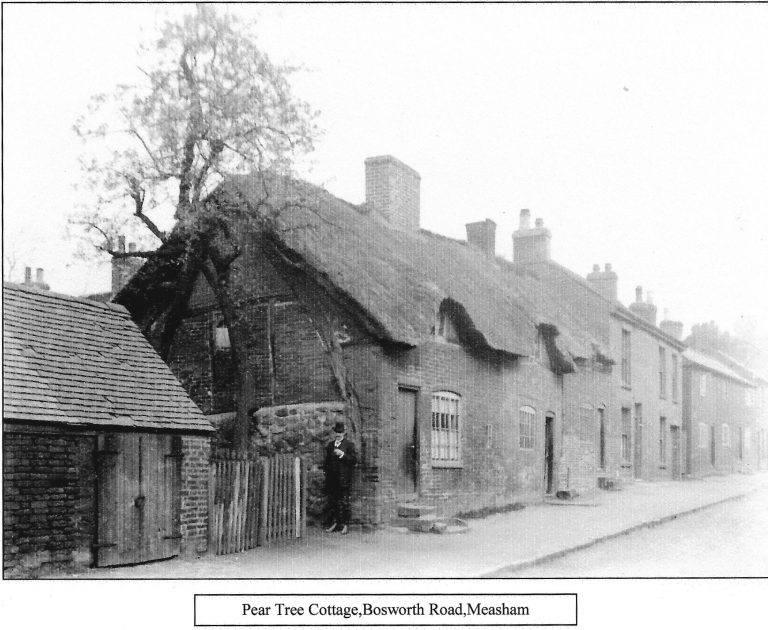

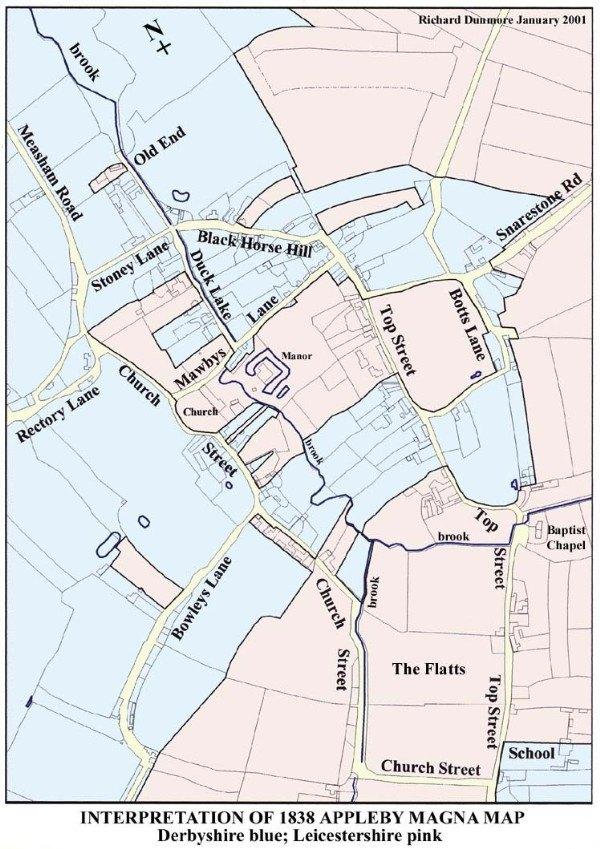

Measham is a large village in north west Leicestershire, England, near the Derbyshire, Staffordshire and Warwickshire boundaries. Our family has a penchant for border straddling, and the Orgill’s of Measham take this a step further living on the boundaries of four counties. Historically it was in an exclave of Derbyshire absorbed into Leicestershire in 1897, so once again we have two sets of county records to search.

ORGILL

Richard Gretton, the baker of Swadlincote and my great grandmother Florence Nightingale Grettons’ father, married Sarah Orgill (1840-1910) in 1861.

(Incidentally, Florence Nightingale Warren nee Gretton’s first child Hildred born in 1900 had the middle name Orgill. Florence’s brother John Orgill Gretton emigrated to USA.)

When they first married, they lived with Sarah’s widowed mother Elizabeth in Measham. Elizabeth Orgill is listed on the 1861 census as a farmer of two acres.