Search Results for 'narrative'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 17, 2023 at 8:17 am #6393

In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Give me an unusual plot structure for a narrative

One unusual plot structure for a narrative could be a “reverse chronological” structure, where the story begins at the end and works backwards in time, revealing events and information in a non-linear way. Another could be a “choose your own adventure” style, where the reader is presented with a series of choices at different points in the story that determine the direction and outcome of the plot.

How would role playing qualify in terms of plot structure?

Role-playing games (RPGs) can be considered a unique form of plot structure because they are interactive and open-ended. In a traditional RPG, the players take on the roles of characters within a fictional setting and work together to create a shared narrative. The plot structure of an RPG is determined by the actions and decisions of the players, rather than a pre-written script. The game master (GM) creates an overarching plot and a set of rules for the players to follow, but the players’ choices and actions will determine the direction and outcome of the story. This makes the plot structure of an RPG fluid and ever-changing, unlike a traditional linear narrative.

What about “Cloud Atlas” in terms of plot structure?

“Cloud Atlas” is a novel written by David Mitchell that was later adapted into a film. It has a complex and non-linear plot structure, which employs multiple storylines that are set in different time periods and locations, and are connected by recurring themes and motifs. The novel is divided into six nested stories, each set in a different time period and location, that are told in a non-linear fashion. The story begins in the 19th century and then jumps back and forth between the 19th, 20th and 23rd century, and each story is interconnected and interrelated, with characters reappearing in different time periods, the events that happen in one story impacting the others. The novel is also notable for its use of different genres, such as science fiction, historical fiction, and thriller, and the way it explores the themes of destiny, reincarnation, and the power of human connection. The film adaptation also used this structure, with the different stories intertwined and characters reprising their roles in different settings and eras.

Take a story thread made of comments. In each comment is a text about characters in a particular plot, location, action etc. The comments are sequential, but they are not necessarily continuous. It is a mix between Cloud Atlas and RPG plot structures. How do you sort something that’s fundamentally non-linear to present it in an accessible way?

One way to sort and present a story thread made of comments that is fundamentally non-linear, yet accessible, is to group the comments based on their content. For example, you could group the comments by characters, and present them in chronological order of their appearance in the story. Another way could be grouping the comments by location, and present them in chronological order of when the action takes place in that particular location. You could also group comments by the type of action taking place, such as combat, conversation, or puzzle-solving, and present them in chronological order of when they occur in the story.

Another approach could be using visual aids, such as mind maps, timelines, or flowcharts, to help organize and present the information in a clear and easy-to-understand way. For example, you could use a mind map to show how different characters are connected, or a timeline to show the chronology of events. Additionally, you could use labels, such as “character introduction,” “location change,” or “plot twist,” to make it clear to the reader what type of information they can expect in each comment.

It’s also important to keep in mind the audience for which you are organizing the story. It should be easy for them to understand and follow the story, and if it’s a game, you should make sure it’s easy for the players to play and make decisions.

March 21, 2022 at 7:05 am #6284In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

To Australia

Grettons

Charles Herbert Gretton 1876-1954

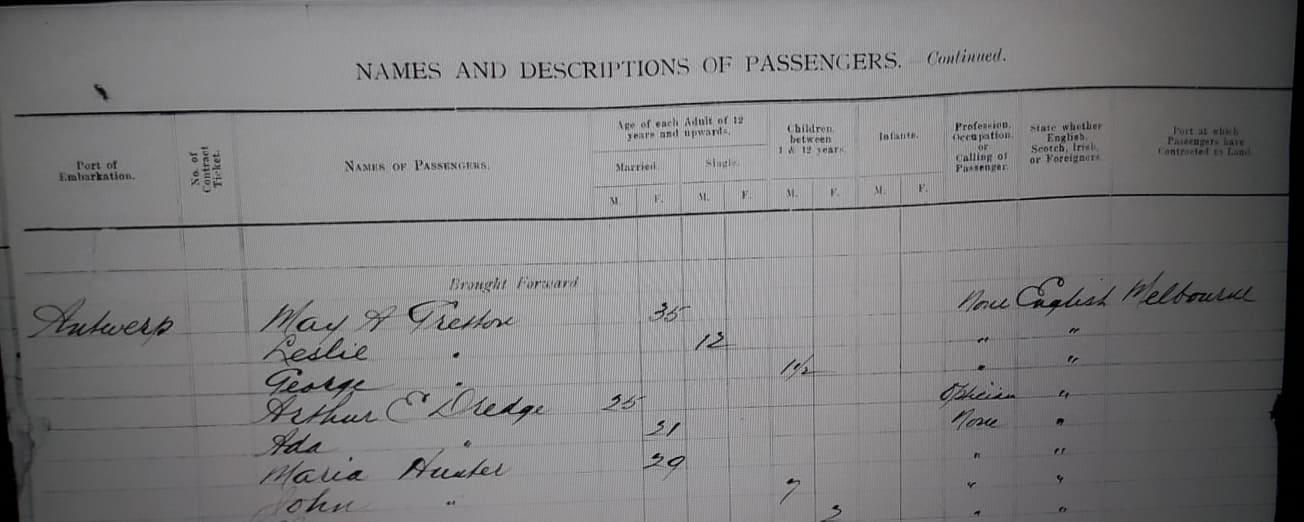

Charles Gretton, my great grandmothers youngest brother, arrived in Sydney Australia on 12 February 1912, having set sail on 5 January 1912 from London. His occupation on the passenger list was stockman, and he was traveling alone. Later that year, in October, his wife and two sons sailed out to join him.

Charles was born in Swadlincote. He married Mary Anne Illsley, a local girl from nearby Church Gresley, in 1898. Their first son, Leslie Charles Bloemfontein Gretton, was born in 1900 in Church Gresley, and their second son, George Herbert Gretton, was born in 1910 in Swadlincote. In 1901 Charles was a colliery worker, and on the 1911 census, his occupation was a sanitary ware packer.

Charles and Mary Anne had two more sons, both born in Footscray: Frank Orgill Gretton in 1914, and Arthur Ernest Gretton in 1920.

On the Australian 1914 electoral rolls, Charles and Mary Ann were living at 72 Moreland Street, Footscray, and in 1919 at 134 Cowper Street, Footscray, and Charles was a labourer. In 1924, Charles was a sub foreman, living at 3, Ryan Street E, Footscray, Australia. On a later electoral register, Charles was a foreman. Footscray is a suburb of Melbourne, and developed into an industrial zone in the second half of the nineteenth century.

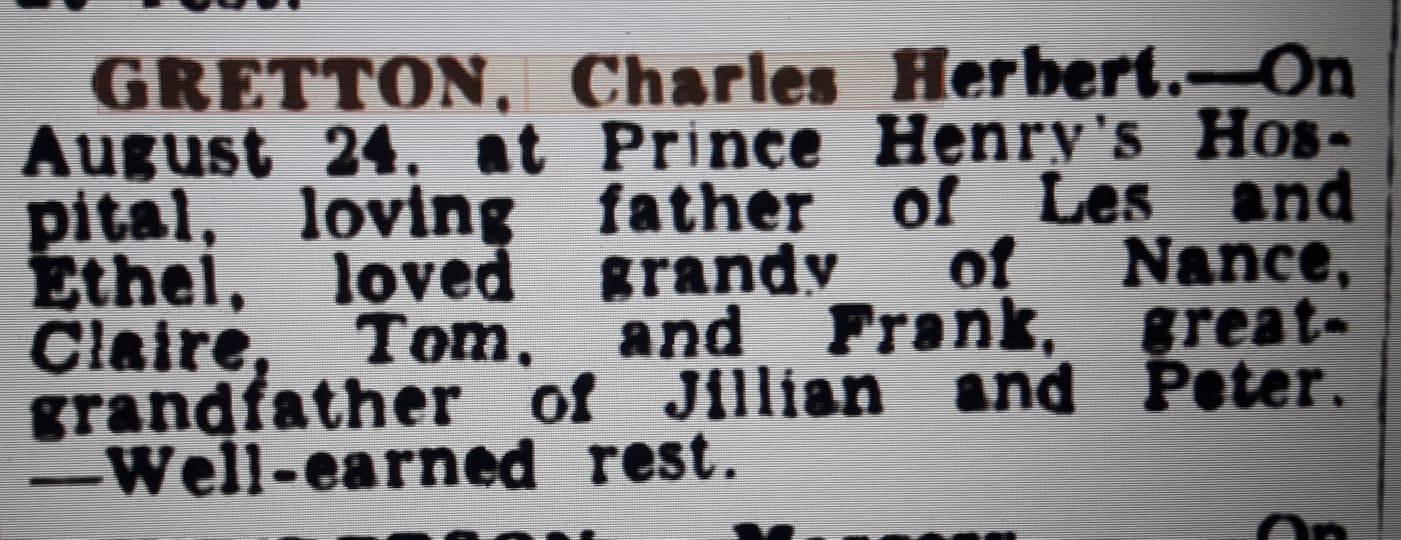

Charles died in Victoria in 1954 at the age of 77. His wife Mary Ann died in 1958.

Charles and Mary Ann Gretton:

Leslie Charles Bloemfontein Gretton 1900-1955

Leslie was an electrician. He married Ethel Christine Halliday, born in 1900 in Footscray, in 1927. They had four children: Tom, Claire, Nancy and Frank. By 1943 they were living in Yallourn. Yallourn, Victoria was a company town in Victoria, Australia built between the 1920s and 1950s to house employees of the State Electricity Commission of Victoria, who operated the nearby Yallourn Power Station complex. However, expansion of the adjacent open-cut brown coal mine led to the closure and removal of the town in the 1980s.

On the 1954 electoral registers, daughter Claire Elizabeth Gretton, occupation teacher, was living at the same address as Leslie and Ethel.

Leslie died in Yallourn in 1955, and Ethel nine years later in 1964, also in Yallourn.

George Herbert Gretton 1910-1970

George married Florence May Hall in 1934 in Victoria, Australia. In 1942 George was listed on the electoral roll as a grocer, likewise in 1949. In 1963 his occupation was a process worker, and in 1968 in Flinders, a horticultural advisor.

George died in Lang Lang, not far from Melbourne, in 1970.

Frank Orgill Gretton 1914-

Arthur Ernest Gretton 1920-

Orgills

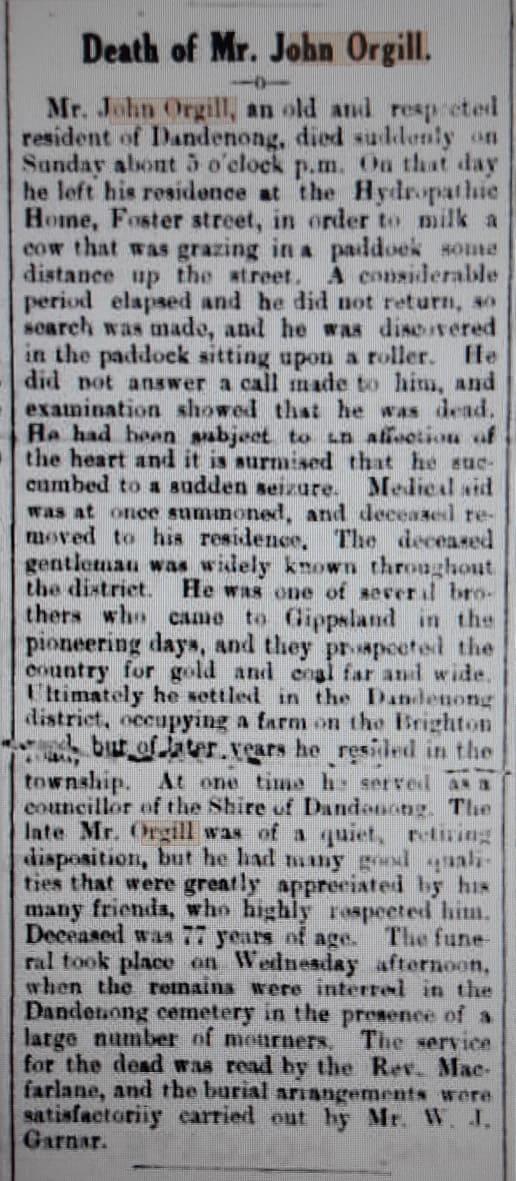

John Orgill 1835-1911

John Orgill was Charles Herbert Gretton’s uncle. He emigrated to Australia in 1865, and married Elizabeth Mary Gladstone 1845-1926 in Victoria in 1870. Their first child was born in December that year, in Dandenong. They had seven children, and their three sons all have the middle name Gladstone.

John Orgill was a councillor for the Shire of Dandenong in 1873, and between 1876 and 1879.

John Orgill:

John Orgill obituary in the South Bourke and Mornington Journal, 21 December 1911:

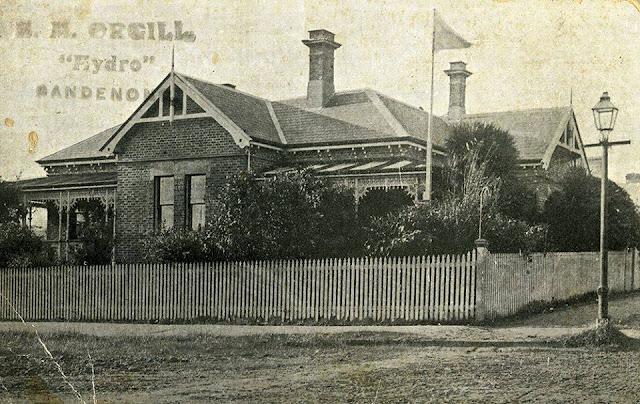

John’s wife Elizabeth Orgill, a teacher and a “a public spirited lady” according to newspaper articles, opened a hydropathic hospital in Dandenong called Gladstone House.

Elizabeth Gladstone Orgill:

On the Old Dandenong website:

Gladstone House hydropathic hospital on the corner of Langhorne and Foster streets (153 Foster Street) Dandenong opened in 1896, working on the theory of water therapy, no medicine or operations. Her husband passed away in 1911 at 77, around similar time Dr Barclay Thompson obtained control of the practice. Mrs Orgill remaining on in some capacity.

Elizabeth Mary Orgill (nee Gladstone) operated Gladstone House until at least 1911, along with another hydropathic hospital (Birthwood) on Cheltenham road. She was the daughter of William Gladstone (Nephew of William Ewart Gladstone, UK prime minister in 1874).

Around 1912 Dr A. E. Taylor took over the location from Dr. Barclay Thompson. Mrs Orgill was still working here but no longer controlled the practice, having given it up to Barclay. Taylor served as medical officer for the Shire for before his death in 1939. After Taylor’s death Dr. T. C. Reeves bought his practice in 1939, later that year being appointed medical officer,

Gladstone Road in Dandenong is named after her family, who owned and occupied a farming paddock in the area on former Police Paddock ground, the Police reserve having earlier been reduced back to Stud Road.

Hydropathy (now known as Hydrotherapy) and also called water cure, is a part of medicine and alternative medicine, in particular of naturopathy, occupational therapy and physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and treatment.

Gladstone House, Dandenong:

John’s brother Robert Orgill 1830-1915 also emigrated to Australia. I met (online) his great great grand daughter Lidya Orgill via the Old Dandenong facebook group.

John’s other brother Thomas Orgill 1833-1908 also emigrated to the same part of Australia.

Thomas Orgill:

One of Thomas Orgills sons was George Albert Orgill 1880-1949:

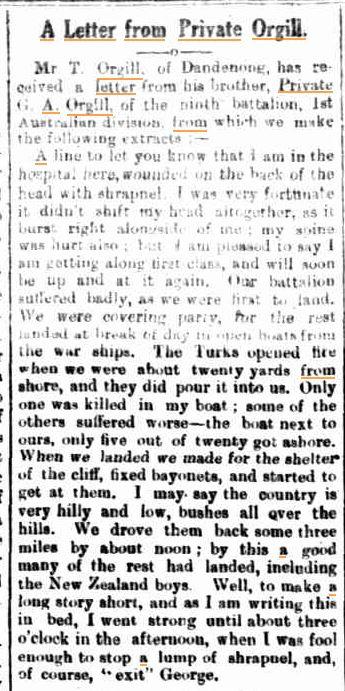

A letter was published in The South Bourke & Mornington Journal (Richmond, Victoria, Australia) on 17 Jun 1915, to Tom Orgill, Emerald Hill (South Melbourne) from hospital by his brother George Albert Orgill (4th Pioneers) describing landing of Covering Party prior to dawn invasion of Gallipoli:

Another brother Henry Orgill 1837-1916 was born in Measham and died in Dandenong, Australia. Henry was a bricklayer living in Measham on the 1861 census. Also living with his widowed mother Elizabeth at that address was his sister Sarah and her husband Richard Gretton, the baker (my great great grandparents). In October of that year he sailed to Melbourne. His occupation was bricklayer on his death records in 1916.

Two of Henry’s sons, Arthur Garfield Orgill born 1888 and Ernest Alfred Orgill born 1880 were killed in action in 1917 and buried in Nord-Pas-de-Calais, France. Another son, Frederick Stanley Orgill, died in 1897 at the age of seven.

A fifth brother, William Orgill 1842- sailed from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1861, at 19 years of age. Four years later in 1865 he sailed from Victoria, Australia to New Zealand.

I assumed I had found all of the Orgill brothers who went to Australia, and resumed research on the Orgills in Measham, in England. A search in the British Newspaper Archives for Orgills in Measham revealed yet another Orgill brother who had gone to Australia.

Matthew Orgill 1828-1907 went to South Africa and to Australia, but returned to Measham.

The Orgill brothers had two sisters. One was my great great great grandmother Sarah, and the other was Hannah. Hannah married Francis Hart in Measham. One of her sons, John Orgill Hart 1862-1909, was born in Measham. On the 1881 census he was a 19 year old carpenters apprentice. Two years later in 1883 he was listed as a joiner on the passenger list of the ship Illawarra, bound for Australia. His occupation at the time of his death in Dandenong in 1909 was contractor.

An additional coincidental note about Dandenong: my step daughter Emily’s Australian partner is from Dandenong.

Housleys

Charles Housley 1823-1856

Charles Housley emigrated to Australia in 1851, the same year that his brother George emigrated to USA. Charles is mentioned in the Narrative on the Letters by Barbara Housley, and appears in the Housley Letters chapters.

Rushbys

George “Mike” Rushby 1933-

Mike moved to Australia from South Africa. His story is a separate chapter.

February 8, 2022 at 2:24 pm #6275In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

“AND NOW ABOUT EMMA”

and a mystery about George

I had overlooked this interesting part of Barbara Housley’s “Narrative on the Letters” initially, perhaps because I was more focused on finding Samuel Housley. But when I did eventually notice, I wondered how I had missed it! In this particularly interesting letter excerpt from Joseph, Barbara has not put the date of the letter ~ unusually, because she did with all of the others. However I dated the letter to later than 1867, because Joseph mentions his wife, and they married in 1867. This is important, because there are two Emma Housleys. Joseph had a sister Emma, born in 1836, two years before Joseph was born. At first glance, one would assume that a reference to Emma in the letters would mean his sister, but Emma the sister was married in Derby in 1858, and by 1869 had four children.

But there was another Emma Housley, born in 1851.

From Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters:

“AND NOW ABOUT EMMA”

A MYSTERY

A very mysterious comment is contained in a letter from Joseph:

“And now about Emma. I have only seen her once and she came to me to get your address but I did not feel at liberty to give it to her until I had wrote to you but however she got it from someone. I think it was in this way. I was so pleased to hear from you in the first place and with John’s family coming to see me I let them read one or two of your letters thinking they would like to hear of you and I expect it was Will that noticed your address and gave it to her. She came up to our house one day when I was at work to know if I had heard from you but I had not heard from you since I saw her myself and then she called again after that and my wife showed her your boys’ portraits thinking no harm in doing so.”

At this point Joseph interrupted himself to thank them for sending the portraits. The next sentence is:

“Your son JOHN I have never seen to know him but I hear he is rather wild,” followed by: “EMMA has been living out service but don’t know where she is now.”

Since Joseph had just been talking about the portraits of George’s three sons, one of whom is John Eley, this could be a reference to things George has written in despair about a teen age son–but could Emma be a first wife and John their son? Or could Emma and John both be the children of a first wife?

Elsewhere, Joseph wrote, “AMY ELEY died 14 years ago. (circa 1858) She left a son and a daughter.”

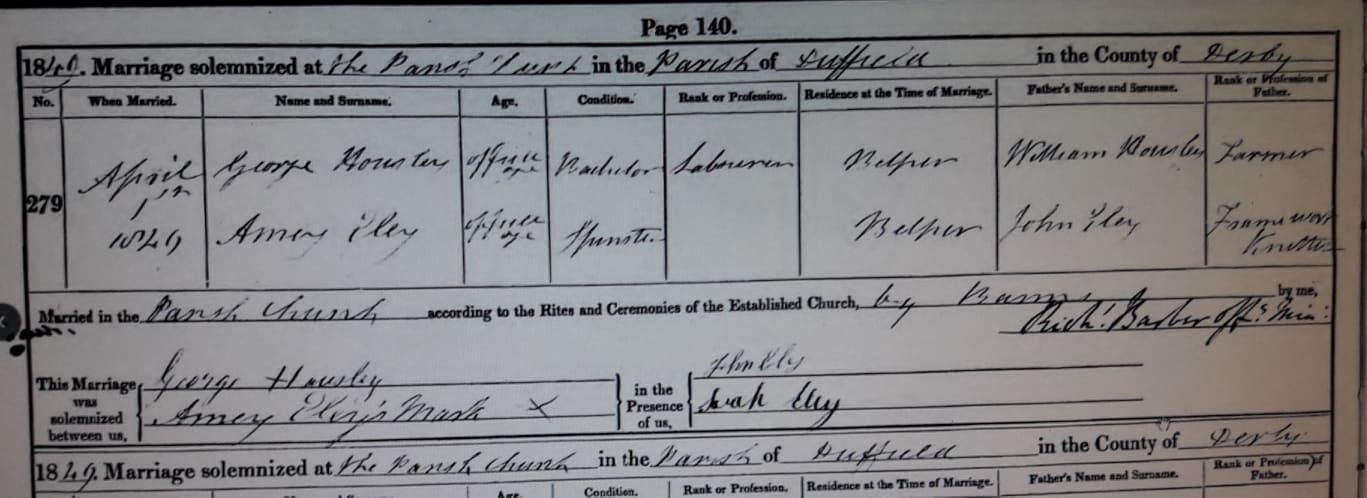

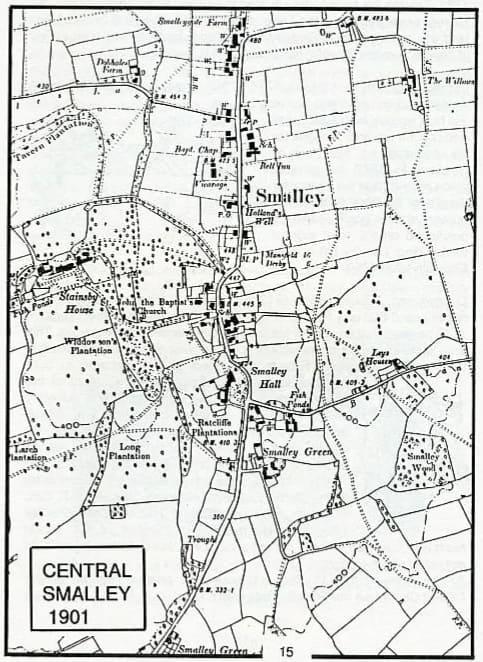

An Amey Eley and a George Housley were married on April 1, 1849 in Duffield which is about as far west of Smalley as Heanor is East. She was the daughter of John, a framework knitter, and Sarah Eley. George’s father is listed as William, a farmer. Amey was described as “of full age” and made her mark on the marriage document.

Anne wrote in August 1854: “JOHN ELEY is living at Derby Station so must take the first opportunity to get the receipt.” Was John Eley Housley named for him?

(John Eley Housley is George Housley’s son in USA, with his second wife, Sarah.)

George Housley married Amey Eley in 1849 in Duffield. George’s father on the register is William Housley, farmer. Amey Eley’s father is John Eley, framework knitter.

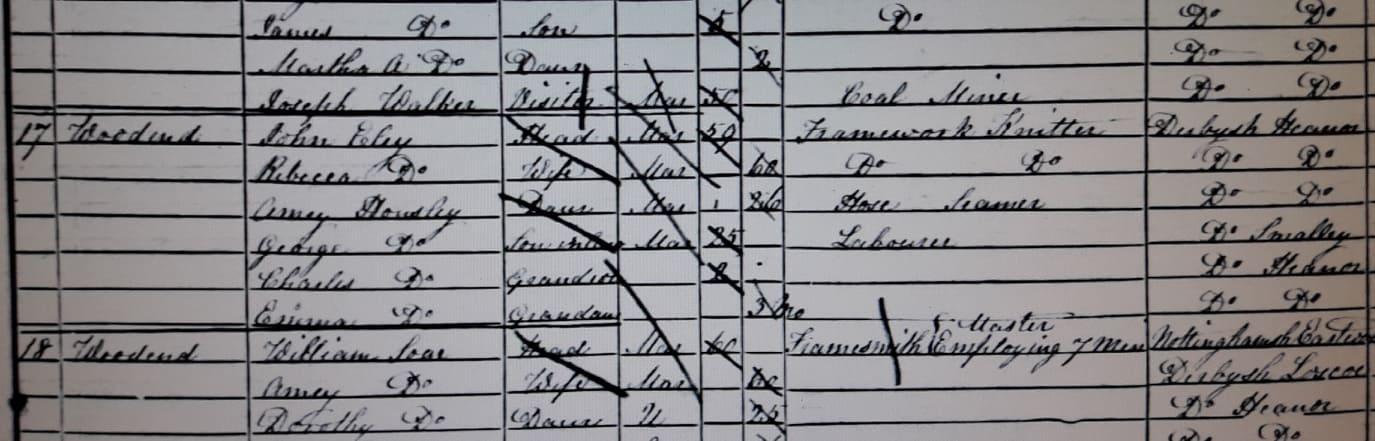

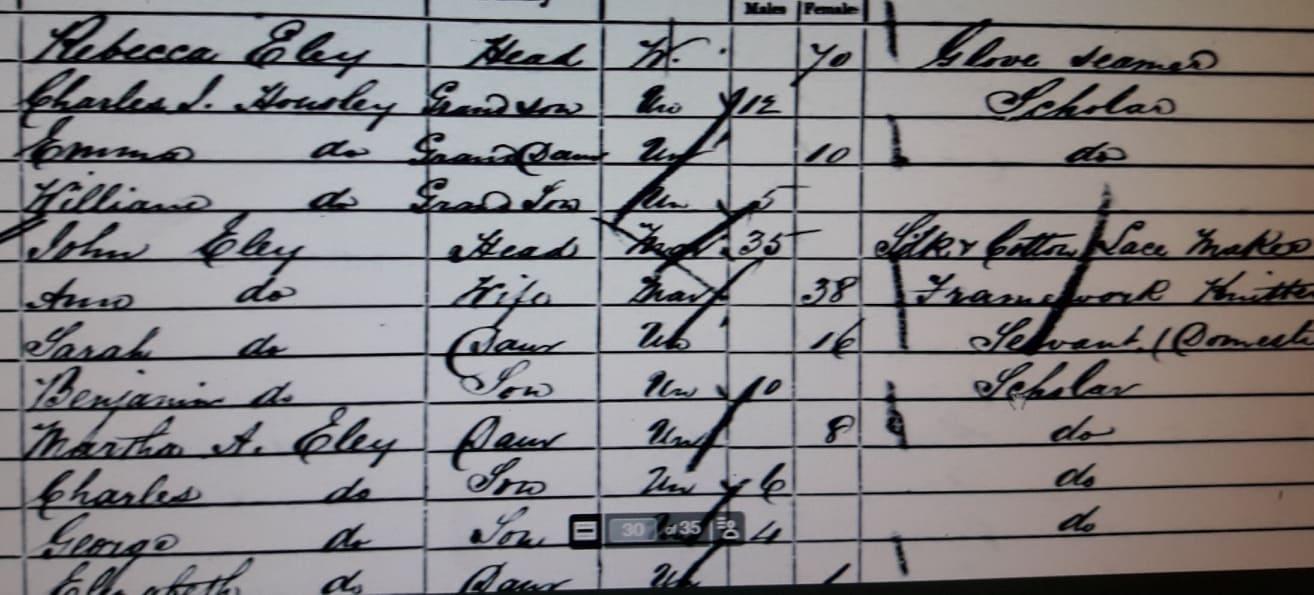

On the 1851 census, George Housley and his wife Amey Housley are living with her parents in Heanor, John Eley, a framework knitter, and his wife Rebecca. Also on the census are Charles J Housley, born in 1849 in Heanor, and Emma Housley, three months old at the time of the census, born in 1851. George’s birth place is listed as Smalley.

On the 31st of July 1851 George Housley arrives in New York. In 1854 George Housley marries Sarah Ann Hill in USA.

On the 1861 census in Heanor, Rebecca Eley was a widow, her husband John having died in 1852, and she had three grandchildren living with her: Charles J Housley aged 12, Emma Housley, 10, and mysteriously a William Housley aged 5! Amey Housley, the childrens mother, died in 1858.

Back to the mysterious comment in Joseph’s letter. Joseph couldn’t have been speaking of his sister Emma. She was married with children by the time Joseph wrote that letter, so was not just out of service, and Joseph would have known where she was. There is no reason to suppose that the sister Emma was trying unsuccessfully to find George’s addresss: she had been sending him letters for years. Joseph must have been referring to George’s daughter Emma.

Joseph comments to George “Your son John…is rather wild.” followed by the remark about Emma’s whereabouts. Could Charles John Housley have used his middle name of John instead of Charles?

As for the child William born five years after George left for USA, despite his name of Housley, which was his mothers married name, we can assume that he was not a Housley ~ not George’s child, anyway. It is not clear who his father was, as Amey did not remarry.

A further excerpt from Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters:

Certainly there was some mystery in George’s life. George apparently wanted his whereabouts kept secret. Anne wrote: “People are at a loss to know where you are. The general idea is you are with Charles. We don’t satisfy them.” In that same letter Anne wrote: “I know you could not help thinking of us very often although you neglected writing…and no doubt would feel grieved for the trouble you at times caused (our mother). She freely forgives all.” Near the end of the letter, Anne added: “Mother sends her love to you and hopes you will write and if you want to tell her anything you don’t want all to see you must write it on a piece of loose paper and put it inside the letter.”

In a letter to George from his sister Emma:

Emma wrote in 1855, “We write in love to your wife and yourself and you must write soon and tell us whether there is a little nephew or niece and what you call them.”

In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “We want to see dear Sarah Ann and the dear little boy. We were much pleased with the “bit of news” you sent.” The bit of news was the birth of John Eley Housley, January 11, 1855. Emma concluded her letter “Give our very kindest love to dear sister and dearest Johnnie.”

It would seem that George Housley named his first son with his second wife after his first wife’s father ~ while he was married to both of them.

Emma Housley

1851-1935

In 1871 Emma was 20 years old and “in service” living as a lodger in West Hallam, not far from Heanor. As she didn’t appear on a 1881 census, I looked for a marriage, but the only one that seemed right in every other way had Emma Housley’s father registered as Ralph Wibberly!

Who was Ralph Wibberly? A family friend or neighbour, perhaps, someone who had been a father figure? The first Ralph Wibberly I found was a blind wood cutter living in Derby. He had a son also called Ralph Wibberly. I did not think Ralph Wibberly would be a very common name, but I was wrong.

I then found a Ralph Wibberly living in Heanor, with a son also named Ralph Wibberly. A Ralph Wibberly married an Emma Salt from Heanor. In 1874, a 36 year old Ralph Wibberly (born in 1838) was on trial in Derby for inflicting grevious bodily harm on William Fretwell of Heanor. His occupation is “platelayer” (a person employed in laying and maintaining railway track.) The jury found him not guilty.

In 1851 a 23 year old Ralph Wibberly (born in 1828) was a prisoner in Derby Gaol. However, Ralph Wibberly, a 50 year old labourer born in 1801 and his son Ralph Wibberly, aged 13 and born in 1838, are living in Belper on the 1851 census. Perhaps the son was the same Ralph Wibberly who was found not guilty of GBH in 1874. This appears to be the one who married Emma Salt, as his wife on the 1871 census is called Emma, and his occupation is “Midland Company Railway labourer”.

Which was the Ralph Wibberly that Emma chose to name as her father on the marriage register? We may never know, but perhaps we can assume it was Ralph Wibberly born in 1801. It is unlikely to be the blind wood cutter from Derby; more likely to be the local Ralph Wibberly. Maybe his son Ralph, who we know was involved in a fight in 1874, was a friend of Emma’s brother Charles John, who was described by Joseph as a “wild one”, although Ralph was 11 years older than Charles John.

Emma Housley married James Slater on Christmas day in Heanor in 1873. Their first child, a daughter, was called Amy. Emma’s mother was Amy Eley. James Slater was a colliery brakesman (employed to work the steam-engine, or other machinery used in raising the coal from the mine.)

It occurred to me to wonder if Emma Housley (George’s daughter) knew Elizabeth, Mary Anne and Catherine (Samuel’s daughters). They were cousins, lived in the vicinity, and they had in common with each other having been deserted by their fathers who were brothers. Emma was born two years after Catherine. Catherine was living with John Benniston, a framework knitter in Heanor, from 1851 to 1861. Emma was living with her grandfather John Ely, a framework knitter in Heanor. In 1861, George Purdy was also living in Heanor. He was listed on the census as a 13 year old coal miner! George Purdy and Catherine Housley married in 1866 in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire ~ just over the county border. Emma’s first child Amy was born in Heanor, but the next two children, Eliza and Lilly, were born in Eastwood, in 1878 and 1880. Catherine and George’s fifth child, my great grandmother Mary Ann Gilman Purdy, was born in Eastwood in 1880, the same year as Lilly Slater.

By 1881 Emma and James Slater were living in Woodlinkin, Codnor and Loscoe, close to Heanor and Eastwood, on the Derbyshire side of the border. On each census up to 1911 their address on the census is Woodlinkin. Emma and James had nine children: six girls and 3 boys, the last, Alfred Frederick, born in 1901.

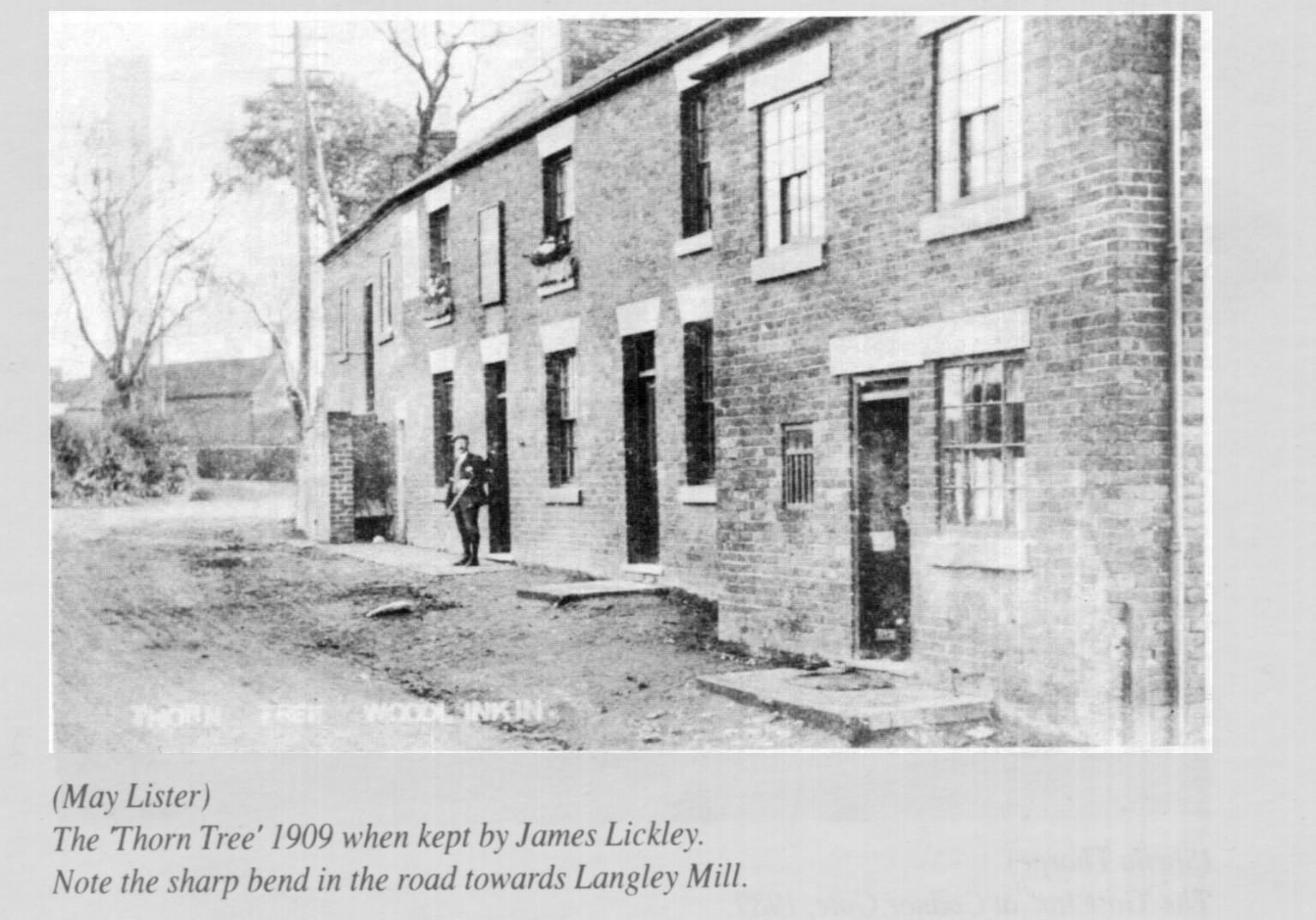

Emma and James lived three doors up from the Thorn Tree pub in Woodlinkin, Codnor:

Emma Slater died in 1935 at the age of 84.

IN

LOVING MEMORY OF

EMMA SLATER

(OF WOODLINKIN)

WHO DIED

SEPT 12th 1935

AGED 84 YEARS

AT RESTCrosshill Cemetery, Codnor, Amber Valley Borough, Derbyshire, England:

Charles John Housley

1949-

February 5, 2022 at 2:16 pm #6273In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

THE NEIGHBORHOODFrom Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters:

In July 1872, Joseph wrote to George who had been gone for 21 years: “You would not know Heanor now. It has got such a large place. They have got a town hall built where Charles’ stone yard was.”

Then Joseph took George on a tour from Smalley to Heanor pointing out all the changes:

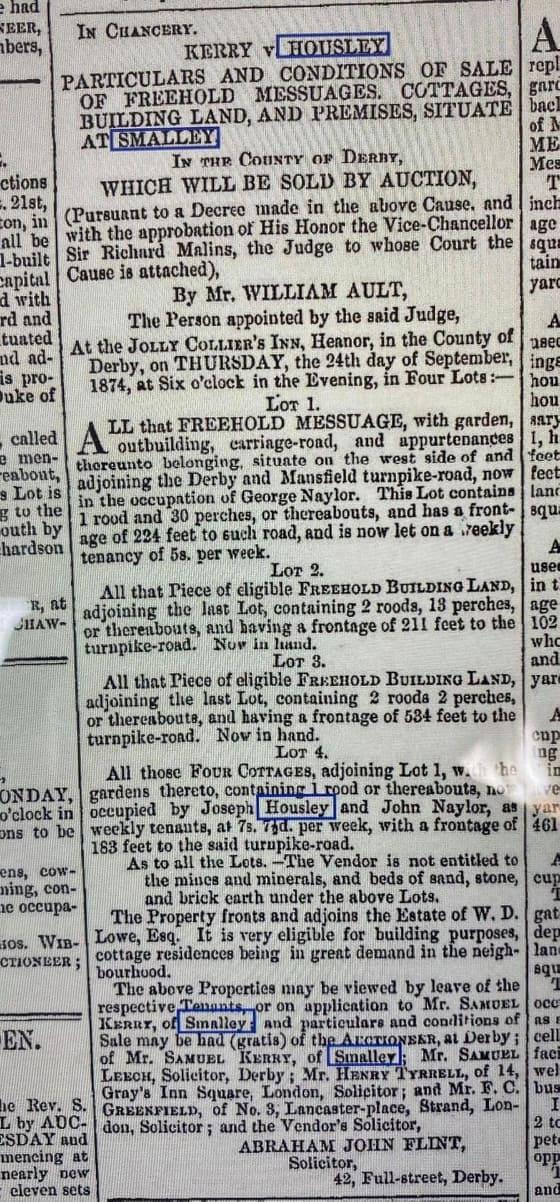

“Now we commence at Firby Brook. There is no public house there. It is turned into a market gardener’s place. Morley smithy stands as it did. You would know Chris Shepperd that used to keep the farm opposite. He is dead and the farm is got into other hands.” (In 1851, Chris Shepherd, age 39, and his widowed mother, Mary, had a farm of 114 acres. Charles Carrington, age 14, worked for them as a “cow boy.” In 1851 Hollingsworths also lived at Morely smithy.) “The Rose and Crown stands and Antony Kerry keeps that yet.” (In 1851, the census listed Kerry as a mason, builder, victicular, and farmer. He lived with his wife and four sons and numerous servants.) “They have pulled down Samuel Kerry’s farm house down and built him one in another place. Now we come to the Bell that was but they have pulled the old one down and made Isaac Potters House into the new Bell.” (In 1851, The Bell was run by Ann Weston, a widow.)

Smalley Roundhouse:

“The old Round House is standing yet but they have took the machine away. The Public House at the top end is kept by Mrs. Turton. I don’t know who she was before she married. Now we get to old Tom Oldknow. The old house is pulled down and a new one is put up but it is gone out of the family altogether. Now Jack is living at Stanley. He married Ann that used to live at Barbers at Smalley. That finishes Smalley. Now for Taghill. The old Jolly Collier is standing yet and a man of the name of Remmington keeps the new one opposite. Jack Foulkes son Jack used to keep that but has left just lately. There is the Nottingham House, Nags Head, Cross Keys and then the Red Lion but houses built on both sides all the way down Taghill. Then we get to the town hall that is built on the ground that Charles’ Stone Yard used to be. There is Joseph Watson’s shop standing yet in the old place. The King of Prussia, the White Lion and Hanks that is the Public House. You see there are more than there used to be. The Magistrate sits at the Town Hall and tries cases there every fortnight.”

.

February 5, 2022 at 1:59 pm #6272In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

The Carringtons

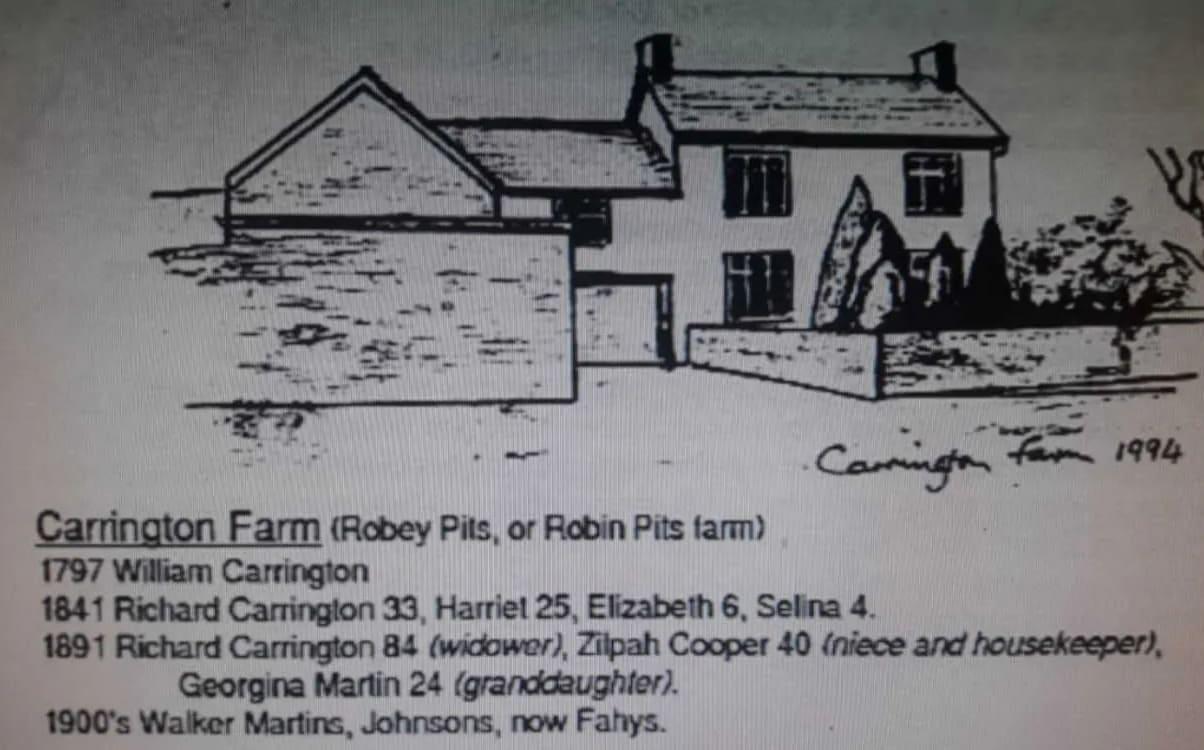

Carrington Farm, Smalley:

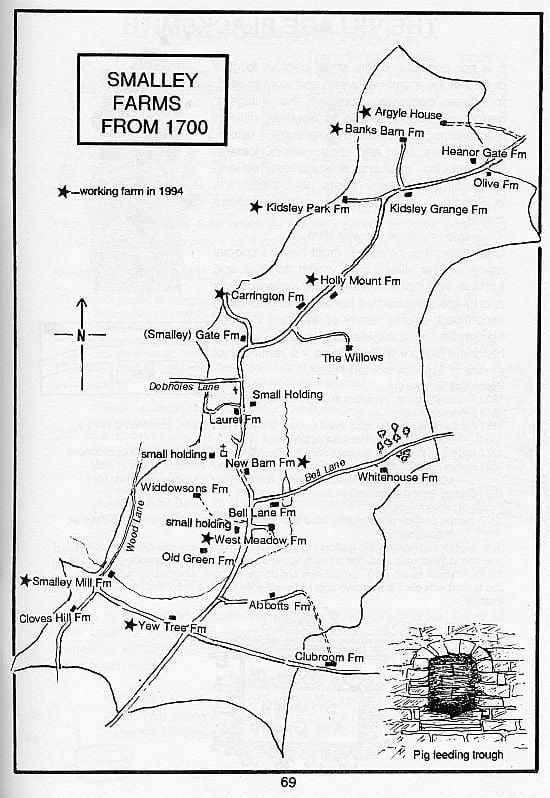

Ellen Carrington was born in 1795. Her father William Carrington 1755-1833 was from Smalley. Her mother Mary Malkin 1765-1838 was from Ellastone, in Staffordshire. Ellastone is on the Derbyshire border and very close to Ashboure, where Ellen married William Housley.

From Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters:

Ellen’s family was evidently rather prominant in Smalley. Two Carringtons (John and William) served on the Parish Council in 1794. Parish records are full of Carrington marriages and christenings.

The letters refer to a variety of “uncles” who were probably Ellen’s brothers, but could be her uncles. These include:

RICHARD

Probably the youngest Uncle, and certainly the most significant, is Richard. He was a trustee for some of the property which needed to be settled following Ellen’s death. Anne wrote in 1854 that Uncle Richard “has got a new house built” and his daughters are “fine dashing young ladies–the belles of Smalley.” Then she added, “Aunt looks as old as my mother.”

Richard was born somewhere between 1808 and 1812. Since Richard was a contemporary of the older Housley children, “Aunt,” who was three years younger, should not look so old!

Richard Carrington and Harriet Faulkner were married in Repton in 1833. A daughter Elizabeth was baptised March 24, 1834. In July 1872, Joseph wrote: “Elizabeth is married too and a large family and is living in Uncle Thomas’s house for he is dead.” Elizabeth married Ayres (Eyres) Clayton of Lascoe. His occupation was listed as joiner and shopkeeper. They were married before 1864 since Elizabeth Clayton witnessed her sister’s marriage. Their children in April 1871 were Selina (1863), Agnes Maria (1866) and Elizabeth Ann (1868). A fourth daughter, Alice Augusta, was born in 1872 or 1873, probably by July 1872 to fit Joseph’s description “large family”! A son Charles Richard was born in 1880.

An Elizabeth Ann Clayton married John Arthur Woodhouse on May 12, 1913. He was a carpenter. His father was a miner. Elizabeth Ann’s father, Ayres, was also a carpenter. John Arthur’s age was given as 25. Elizabeth Ann’s age was given as 33 or 38. However, if she was born in 1868, her age would be 45. Possibly this is another case of a child being named for a deceased sibling. If she were 38 and born in 1875, she would fill the gap between Alice Augusta and Charles Richard.

Selina Clayton, who would have been 18, is not listed in the household in 1881. She died on June 11, 1914 at age 51. Agnes Maria Clayton died at the age of 25 and was buried March 31, 1891. Charles Richard died at the age of 5 and was buried on February 4, 1886. A Charles James Clayton, 18 months, was buried June 8, 1889 in Heanor.

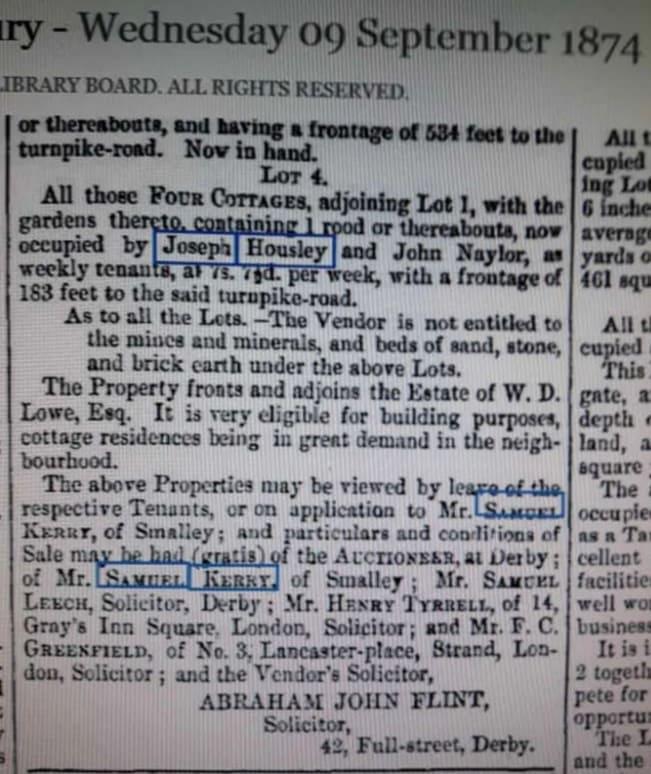

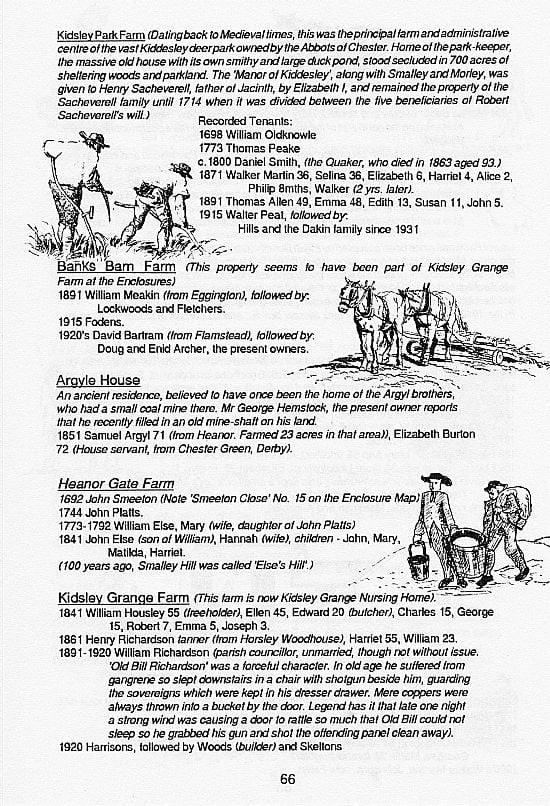

Richard Carrington’s second daughter, Selina, born in 1837, married Walker Martin (b.1835) on February 11, 1864 and they were living at Kidsley Park Farm in 1872, according to a letter from Joseph, and, according to the census, were still there in 1881. This 100 acre farm was formerly the home of Daniel Smith and his daughter Elizabeth Davy Barber. Selina and Walker had at least five children: Elizabeth Ann (1865), Harriet Georgianna (1866/7), Alice Marian (September 6, 1868), Philip Richard (1870), and Walker (1873). In December 1972, Joseph mentioned the death of Philip Walker, a farmer of Prospect Farm, Shipley. This was probably Walker Martin’s grandfather, since Walker was born in Shipley. The stock was to be sold the following Monday, but his daughter (Walker’s mother?) died the next day. Walker’s father was named Thomas. An Annie Georgianna Martin age 13 of Shipley died in April of 1859.

Selina Martin died on October 29, 1906 but her estate was not settled until November 14, 1910. Her gross estate was worth L223.56. Her son Walker and her daughter Harriet Georgiana were her trustees and executers. Walker was to get Selina’s half of Richard’s farm. Harriet Georgiana and Alice Marian were to be allowed to live with him. Philip Richard received L25. Elizabeth Ann was already married to someone named Smith.

Richard and Harriet may also have had a son George. In 1851 a Harriet Carrington and her three year old son George were living with her step-father John Benniston in Heanor. John may have been recently widowed and needed her help. Or, the Carrington home may have been inadequate since Anne reported a new one was built by 1854. Selina’s second daughter’s name testifies to the presence of a “George” in the family! Could the death of this son account for the haggard appearance Anne described when she wrote: “Aunt looks as old as my mother?”

Harriet was buried May 19, 1866. She was 55 when she died.In 1881, Georgianna then 14, was living with her grandfather and his niece, Zilpah Cooper, age 38–who lived with Richard on his 63 acre farm as early as 1871. A Zilpah, daughter of William and Elizabeth, was christened October 1843. Her brother, William Walter, was christened in 1846 and married Anna Maria Saint in 1873. There are four Selina Coopers–one had a son William Thomas Bartrun Cooper christened in 1864; another had a son William Cooper christened in 1873.

Our Zilpah was born in Bretley 1843. She died at age 49 and was buried on September 24, 1892. In her will, which was witnessed by Selina Martin, Zilpah’s sister, Frances Elizabeth Cleave, wife of Horatio Cleave of Leicester is mentioned. James Eley and Francis Darwin Huish (Richard’s soliciter) were executers.

Richard died June 10, 1892, and was buried on June 13. He was 85. As might be expected, Richard’s will was complicated. Harriet Georgiana Martin and Zilpah Cooper were to share his farm. If neither wanted to live there it was to go to Georgiana’s cousin Selina Clayton. However, Zilpah died soon after Richard. Originally, he left his piano, parlor and best bedroom furniture to his daughter Elizabeth Clayton. Then he revoked everything but the piano. He arranged for the payment of £150 which he owed. Later he added a codicil explaining that the debt was paid but he had borrowed £200 from someone else to do it!

Richard left a good deal of property including: The house and garden in Smalley occupied by Eyres Clayton with four messuages and gardens adjoining and large garden below and three messuages at the south end of the row with the frame work knitters shop and garden adjoining; a dwelling house used as a public house with a close of land; a small cottage and garden and four cottages and shop and gardens.

THOMAS

In August 1854, Anne wrote “Uncle Thomas is about as usual.” A Thomas Carrington married a Priscilla Walker in 1810.

Their children were baptised in August 1830 at the same time as the Housley children who at that time ranged in age from 3 to 17. The oldest of Thomas and Priscilla’s children, Henry, was probably at least 17 as he was married by 1836. Their youngest son, William Thomas, born 1830, may have been Mary Ellen Weston’s beau. However, the only Richard whose christening is recorded (1820), was the son of Thomas and Lucy. In 1872 Joseph reported that Richard’s daughter Elizabeth was married and living in Uncle Thomas’s house. In 1851, Alfred Smith lived in house 25, Foulks lived in 26, Thomas and Priscilla lived in 27, Bennetts lived in 28, Allard lived in 29 and Day lived in 30. Thomas and Priscilla do not appear in 1861. In 1871 Elizabeth Ann and Ayres Clayton lived in House 54. None of the families listed as neighbors in 1851 remained. However, Joseph Carrington, who lived in house 19 in 1851, lived in house 51 in 1871.

JOHN

In August 1854, Anne wrote: “Uncle John is with Will and Frank has been home in a comfortable place in Cotmanhay.” Although John and William are two of the most popular Carrington names, only two John’s have sons named William. John and Rachel Buxton Carrington had a son William christened in 1788. At the time of the letters this John would have been over 100 years old. Their son John and his wife Ann had a son William who was born in 1805. However, this William age 46 was living with his widowed mother in 1851. A Robert Carrington and his wife Ann had a son John born 1n 1805. He would be the right age to be a brother to Francis Carrington discussed below. This John was living with his widowed mother in 1851 and was unmarried. There are no known Williams in this family grouping. A William Carrington of undiscovered parentage was born in 1821. It is also possible that the Will in question was Anne’s brother Will Housley.

–Two Francis Carringtons appear in the 1841 census both of them aged 35. One is living with Richard and Harriet Carrington. The other is living next door to Samuel and Ellen Carrington Kerry (the trustee for “father’s will”!). The next name in this sequence is John Carrington age 15 who does not seem to live with anyone! but may be part of the Kerry household.

FRANK (see above)

While Anne did not preface her mention of the name Frank with an “Uncle,” Joseph referred to Uncle Frank and James Carrington in the same sentence. A James Carrington was born in 1814 and had a wife Sarah. He worked as a framework knitter. James may have been a son of William and Anne Carrington. He lived near Richard according to the 1861 census. Other children of William and Anne are Hannah (1811), William (1815), John (1816), and Ann (1818). An Ann Carrington married a Frank Buxton in 1819. This might be “Uncle Frank.”

An Ellen Carrington was born to John and Rachel Carrington in 1785. On October 25, 1809, a Samuel Kerry married an Ellen Carrington. However this Samuel Kerry is not the trustee involved in settling Ellen’s estate. John Carrington died July 1815.

William and Mary Carrington:

February 5, 2022 at 10:50 am #6271

February 5, 2022 at 10:50 am #6271In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

FRIENDS AND NEIGHBORS

from Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters:

George apparently asked about old friends and acquaintances and the family did their best to answer although Joseph wrote in 1873: “There is very few of your old cronies that I know of knocking about.”

In Anne’s first letter she wrote about a conversation which Robert had with EMMA LYON before his death and added “It (his death) was a great trouble to Lyons.” In her second letter Anne wrote: “Emma Lyon is to be married September 5. I am going the Friday before if all is well. There is every prospect of her being comfortable. MRS. L. always asks after you.” In 1855 Emma wrote: “Emma Lyon now Mrs. Woolhouse has got a fine boy and a pretty fuss is made with him. They call him ALFRED LYON WOOLHOUSE.”

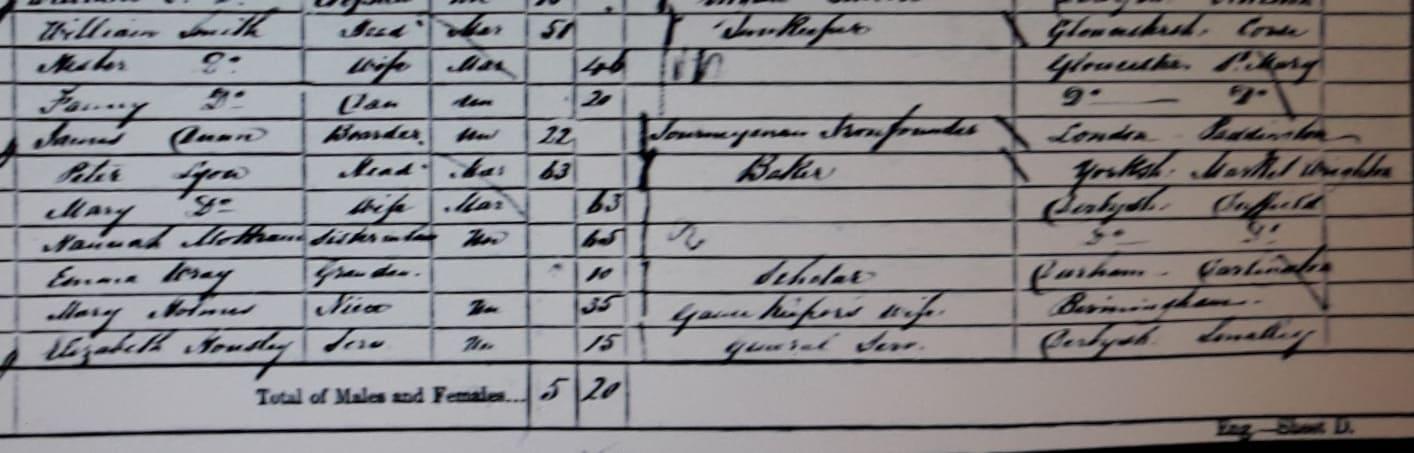

(Interesting to note that Elizabeth Housley, the eldest daughter of Samuel and Elizabeth, was living with a Lyon family in Derby in 1861, after she left Belper workhouse. The Emma listed on the census in 1861 was 10 years old, and so can not be the Emma Lyon mentioned here, but it’s possible, indeed likely, that Peter Lyon the baker was related to the Lyon’s who were friends of the Housley’s. The mention of a sea captain in the Lyon family begs the question did Elizabeth Housley meet her husband, George William Stafford, a seaman, through some Lyon connections, but to date this remains a mystery.)

Elizabeth Housley living with Peter Lyon and family in Derby St Peters in 1861:

A Henrietta Lyon was married in 1860. Her father was Matthew, a Navy Captain. The 1857 Derby Directory listed a Richard Woolhouse, plumber, glazier, and gas fitter on St. Peter’s Street. Robert lived in St. Peter’s parish at the time of his death. An Alfred Lyon, son of Alfred and Jemima Lyon 93 Friargate, Derby was baptised on December 4, 1877. An Allen Hewley Lyon, born February 1, 1879 was baptised June 17 1879.

Anne wrote in August 1854: “KERRY was married three weeks since to ELIZABETH EATON. He has left Smith some time.” Perhaps this was the same person referred to by Joseph: “BILL KERRY, the blacksmith for DANIEL SMITH, is working for John Fletcher lace manufacturer.” According to the 1841 census, Elizabeth age 12, was the oldest daughter of Thomas and Rebecca Eaton. She would certainly have been of marriagable age in 1854. A William Kerry, age 14, was listed as a blacksmith’s apprentice in the 1851 census; but another William Kerry who was 29 in 1851 was already working for Daniel Smith as a blacksmith. REBECCA EATON was listed in the 1851 census as a widow serving as a nurse in the John Housley household. The 1881 census lists the family of William Kerry, blacksmith, as Jane, 19; William 13; Anne, 7; and Joseph, 4. Elizabeth is not mentioned but Bill is not listed as a widower.

Anne also wrote in 1854 that she had not seen or heard anything of DICK HANSON for two years. Joseph wrote that he did not know Old BETTY HANSON’S son. A Richard Hanson, age 24 in 1851, lived with a family named Moore. His occupation was listed as “journeyman knitter.” An Elizabeth Hanson listed as 24 in 1851 could hardly be “Old Betty.” Emma wrote in June 1856 that JOE OLDKNOW age 27 had married Mrs. Gribble’s servant age 17.

Anne wrote that “JOHN SPENCER had not been since father died.” The only John Spencer in Smalley in 1841 was four years old. He would have been 11 at the time of William Housley’s death. Certainly, the two could have been friends, but perhaps young John was named for his grandfather who was a crony of William’s living in a locality not included in the Smalley census.

TAILOR ALLEN had lost his wife and was still living in the old house in 1872. JACK WHITE had died very suddenly, and DR. BODEN had died also. Dr. Boden’s first name was Robert. He was 53 in 1851, and was probably the Robert, son of Richard and Jane, who was christened in Morely in 1797. By 1861, he had married Catherine, a native of Smalley, who was at least 14 years his junior–18 according to the 1871 census!

Among the family’s dearest friends were JOSEPH AND ELIZABETH DAVY, who were married some time after 1841. Mrs. Davy was born in 1812 and her husband in 1805. In 1841, the Kidsley Park farm household included DANIEL SMITH 72, Elizabeth 29 and 5 year old Hannah Smith. In 1851, Mr. Davy’s brother William and 10 year old Emma Davy were visiting from London. Joseph reported the death of both Davy brothers in 1872; Joseph apparently died first.

Mrs. Davy’s father, was a well known Quaker. In 1856, Emma wrote: “Mr. Smith is very hearty and looks much the same.” He died in December 1863 at the age of 94. George Fox, the founder of the Quakers visited Kidsley Park in 1650 and 1654.

Mr. Davy died in 1863, but in 1854 Anne wrote how ill he had been for two years. “For two last winters we never thought he would live. He is now able to go out a little on the pony.” In March 1856, his wife wrote, “My husband is in poor health and fell.” Later in 1856, Emma wrote, “Mr. Davy is living which is a great wonder. Mrs. Davy is very delicate but as good a friend as ever.”

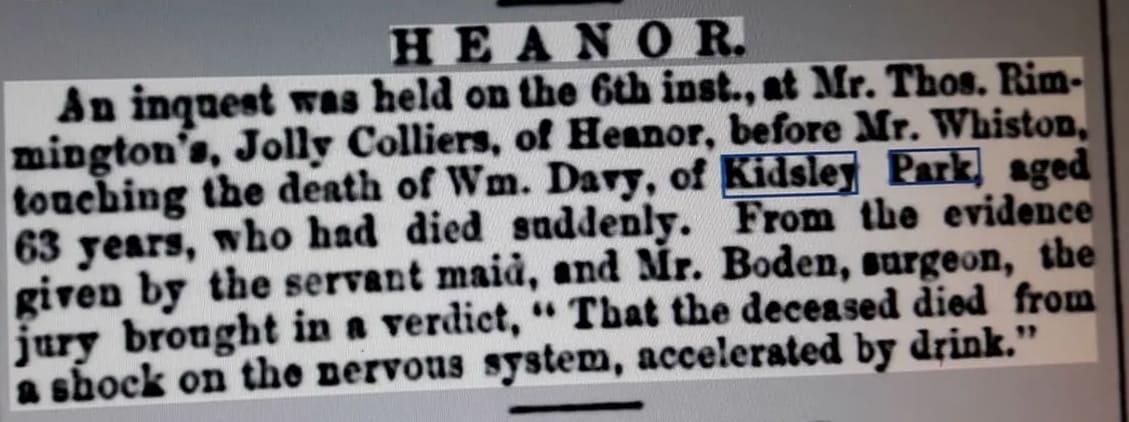

In The Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal, 15 May 1863:

Whenever the girls sent greetings from Mrs. Davy they used her Quaker speech pattern of “thee and thy.” Mrs. Davy wrote to George on March 21 1856 sending some gifts from his sisters and a portrait of their mother–“Emma is away yet and A is so much worse.” Mrs. Davy concluded: “With best wishes for thy health and prosperity in this world and the next I am thy sincere friend.”

Mrs. Davy later remarried. Her new husband was W.T. BARBER. The 1861 census lists William Barber, 35, Bachelor of Arts, Cambridge, living with his 82 year old widowed mother on an 135 acre farm with three servants. One of these may have been the Ann who, according to Joseph, married Jack Oldknow. By 1871 the farm, now occupied by William, 47 and Elizabeth, 57, had grown to 189 acres. Meanwhile, Kidsley Park Farm became the home of the Housleys’ cousin Selina Carrington and her husband Walker Martin. Both Barbers were still living in 1881.

Mrs. Davy was described in Kerry’s History of Smalley as “an accomplished and exemplary lady.” A piece of her poetry “Farewell to Kidsley Park” was published in the history. It was probably written when Elizabeth moved to the Barber farm. Emma sent one of her poems to George. It was supposed to be about their house. “We have sent you a piece of poetry that Mrs. Davy composed about our ‘Old House.’ I am sure you will like it though you may not understand all the allusions she makes use of as well as we do.”

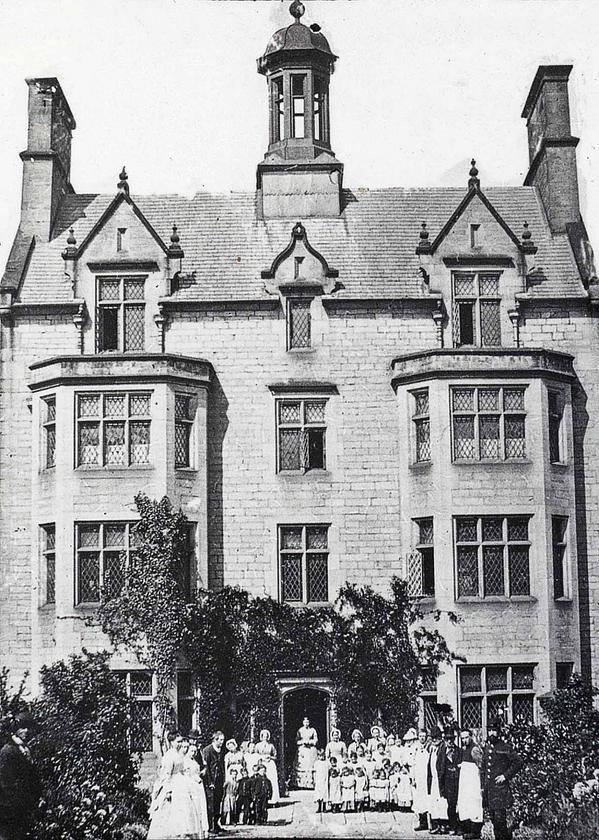

Kiddsley Park Farm, Smalley, in 1898. (note that the Housley’s lived at Kiddsley Grange Farm, and the Davy’s at neighbouring Kiddsley Park Farm)

Emma was not sure if George wanted to hear the local gossip (“I don’t know whether such little particulars will interest you”), but shared it anyway. In November 1855: “We have let the house to Mr. Gribble. I dare say you know who he married, Matilda Else. They came from Lincoln here in March. Mrs. Gribble gets drunk nearly every day and there are such goings on it is really shameful. So you may be sure we have not very pleasant neighbors but we have very little to do with them.”

John Else and his wife Hannah and their children John and Harriet (who were born in Smalley) lived in Tag Hill in 1851. With them lived a granddaughter Matilda Gribble age 3 who was born in Lincoln. A Matilda, daughter of John and Hannah, was christened in 1815. (A Sam Else died when he fell down the steps of a bar in 1855.)

February 4, 2022 at 3:17 pm #6269In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

From Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters.

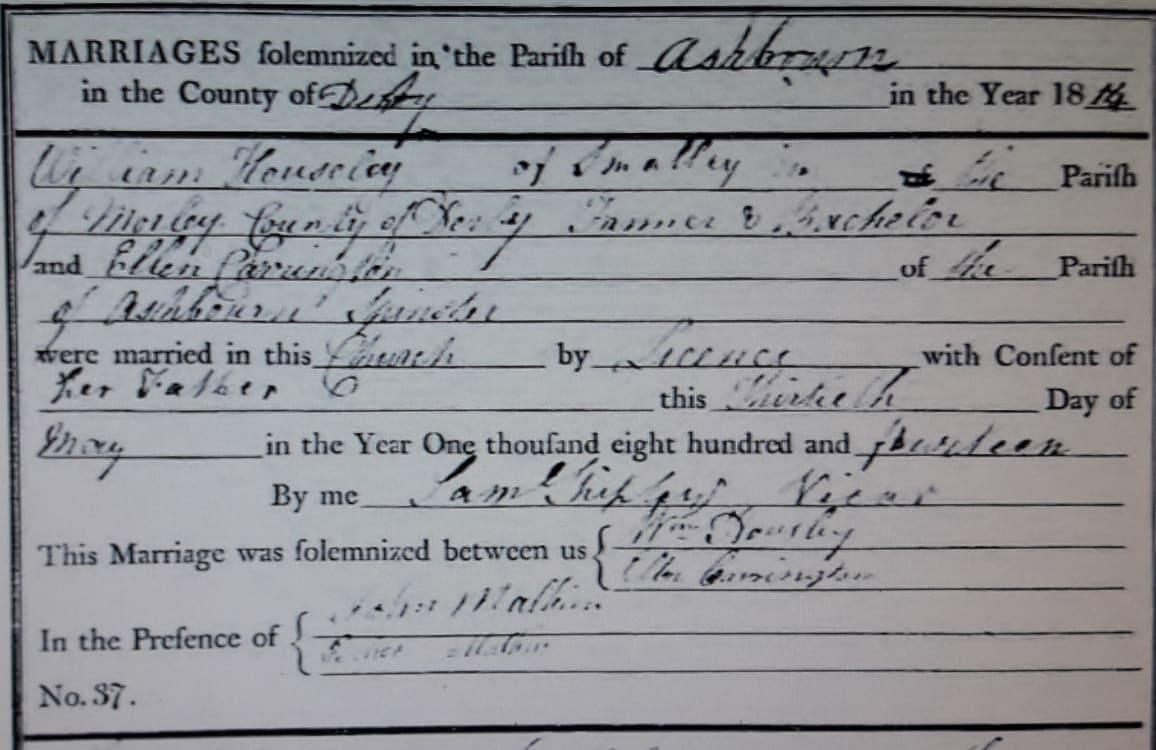

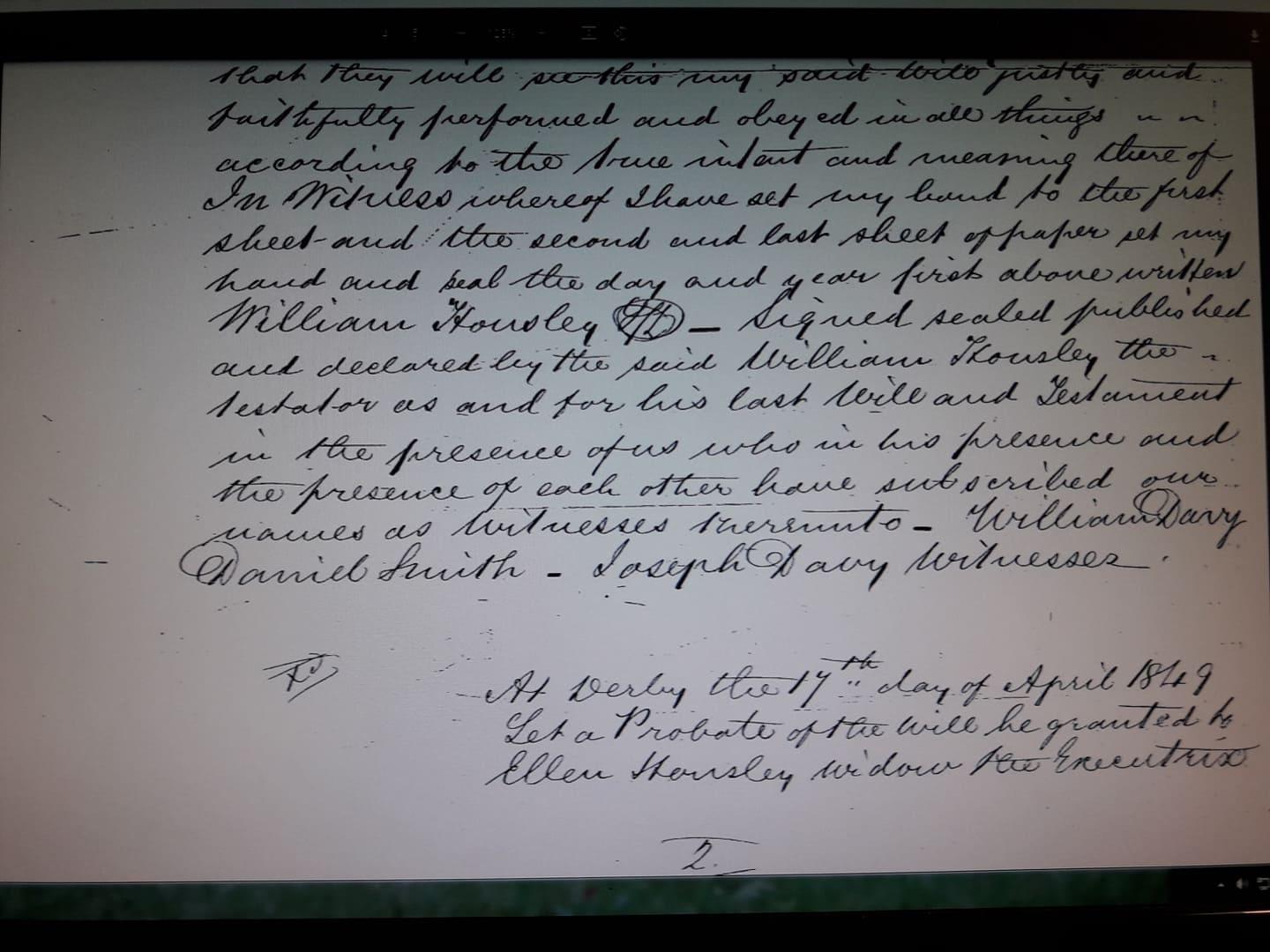

William Housley (1781-1848) and Ellen Carrington were married on May 30, 1814 at St. Oswald’s church in Ashbourne. William died in 1848 at the age of 67 of “disease of lungs and general debility”. Ellen died in 1872.

Marriage of William Housley and Ellen Carrington in Ashbourne in 1814:

Parish records show three children for William and his first wife, Mary, Ellens’ sister, who were married December 29, 1806: Mary Ann, christened in 1808 and mentioned frequently in the letters; Elizabeth, christened in 1810, but never mentioned in any letters; and William, born in 1812, probably referred to as Will in the letters. Mary died in 1813.

William and Ellen had ten children: John, Samuel, Edward, Anne, Charles, George, Joseph, Robert, Emma, and Joseph. The first Joseph died at the age of four, and the last son was also named Joseph. Anne never married, Charles emigrated to Australia in 1851, and George to USA, also in 1851. The letters are to George, from his sisters and brothers in England.

The following are excerpts of those letters, including excerpts of Barbara Housley’s “Narrative on Historic Letters”. They are grouped according to who they refer to, rather than chronological order.

ELLEN HOUSLEY 1795-1872

Joseph wrote that when Emma was married, Ellen “broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby didn’t agree with her so she left again leaving her things behind and came to live with John in the new house where she died.” Ellen was listed with John’s household in the 1871 census.

In May 1872, the Ilkeston Pioneer carried this notice: “Mr. Hopkins will sell by auction on Saturday next the eleventh of May 1872 the whole of the useful furniture, sewing machine, etc. nearly new on the premises of the late Mrs. Housley at Smalley near Heanor in the county of Derby. Sale at one o’clock in the afternoon.”Ellen’s family was evidently rather prominant in Smalley. Two Carringtons (John and William) served on the Parish Council in 1794. Parish records are full of Carrington marriages and christenings; census records confirm many of the family groupings.

In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “Mother looks as well as ever and was told by a lady the other day that she looked handsome.” Later she wrote: “Mother is as stout as ever although she sometimes complains of not being able to do as she used to.”

Mary’s children:

MARY ANN HOUSLEY 1808-1878

There were hard feelings between Mary Ann and Ellen and her children. Anne wrote: “If you remember we were not very friendly when you left. They never came and nothing was too bad for Mary Ann to say of Mother and me, but when Robert died Mother sent for her to the funeral but she did not think well to come so we took no more notice. She would not allow her children to come either.”

Mary Ann was unlucky in love! In Anne’s second letter she wrote: “William Carrington is paying Mary Ann great attention. He is living in London but they write to each other….We expect it will be a match.” Apparantly the courtship was stormy for in 1855, Emma wrote: “Mary Ann’s wedding with William Carrington has dropped through after she had prepared everything, dresses and all for the occassion.” Then in 1856, Emma wrote: “William Carrington and Mary Ann are separated. They wore him out with their nonsense.” Whether they ever married is unclear. Joseph wrote in 1872: “Mary Ann was married but her husband has left her. She is in very poor health. She has one daughter and they are living with their mother at Smalley.”

Regarding William Carrington, Emma supplied this bit of news: “His sister, Mrs. Lily, has eloped with a married man. Is she not a nice person!”

WILLIAM HOUSLEY JR. 1812-1890

According to a letter from Anne, Will’s two sons and daughter were sent to learn dancing so they would be “fit for any society.” Will’s wife was Dorothy Palfry. They were married in Denby on October 20, 1836 when Will was 24. According to the 1851 census, Will and Dorothy had three sons: Alfred 14, Edwin 12, and William 10. All three boys were born in Denby.

In his letter of May 30, 1872, after just bemoaning that all of his brothers and sisters are gone except Sam and John, Joseph added: “Will is living still.” In another 1872 letter Joseph wrote, “Will is living at Heanor yet and carrying on his cattle dealing.” The 1871 census listed Will, 59, and his son William, 30, of Lascoe Road, Heanor, as cattle dealers.

Ellen’s children:

JOHN HOUSLEY 1815-1893

John married Sarah Baggally in Morely in 1838. They had at least six children. Elizabeth (born 2 May 1838) was “out service” in 1854. In her “third year out,” Elizabeth was described by Anne as “a very nice steady girl but quite a woman in appearance.” One of her positions was with a Mrs. Frearson in Heanor. Emma wrote in 1856: “Elizabeth is still at Mrs. Frearson. She is such a fine stout girl you would not know her.” Joseph wrote in 1872 that Elizabeth was in service with Mrs. Eliza Sitwell at Derby. (About 1850, Miss Eliza Wilmot-Sitwell provided for a small porch with a handsome Norman doorway at the west end of the St. John the Baptist parish church in Smalley.)

According to Elizabeth’s birth certificate and the 1841 census, John was a butcher. By 1851, the household included a nurse and a servant, and John was listed as a “victular.” Anne wrote in February 1854, “John has left the Public House a year and a half ago. He is living where Plumbs (Ann Plumb witnessed William’s death certificate with her mark) did and Thomas Allen has the land. He has been working at James Eley’s all winter.” In 1861, Ellen lived with John and Sarah and the three boys.

John sold his share in the inheritance from their mother and disappeared after her death. (He died in Doncaster, Yorkshire, in 1893.) At that time Charles, the youngest would have been 21. Indeed, Joseph wrote in July 1872: “John’s children are all grown up”.

In May 1872, Joseph wrote: “For what do you think, John has sold his share and he has acted very bad since his wife died and at the same time he sold all his furniture. You may guess I have never seen him but once since poor mother’s funeral and he is gone now no one knows where.”

In February 1874 Joseph wrote: “You want to know what made John go away. Well, I will give you one reason. I think I told you that when his wife died he persuaded me to leave Derby and come to live with him. Well so we did and dear Harriet to keep his house. Well he insulted my wife and offered things to her that was not proper and my dear wife had the power to resist his unmanly conduct. I did not think he could of served me such a dirty trick so that is one thing dear brother. He could not look me in the face when we met. Then after we left him he got a woman in the house and I suppose they lived as man and wife. She caught the small pox and died and there he was by himself like some wild man. Well dear brother I could not go to him again after he had served me and mine as he had and I believe he was greatly in debt too so that he sold his share out of the property and when he received the money at Belper he went away and has never been seen by any of us since but I have heard of him being at Sheffield enquiring for Sam Caldwell. You will remember him. He worked in the Nag’s Head yard but I have heard nothing no more of him.”

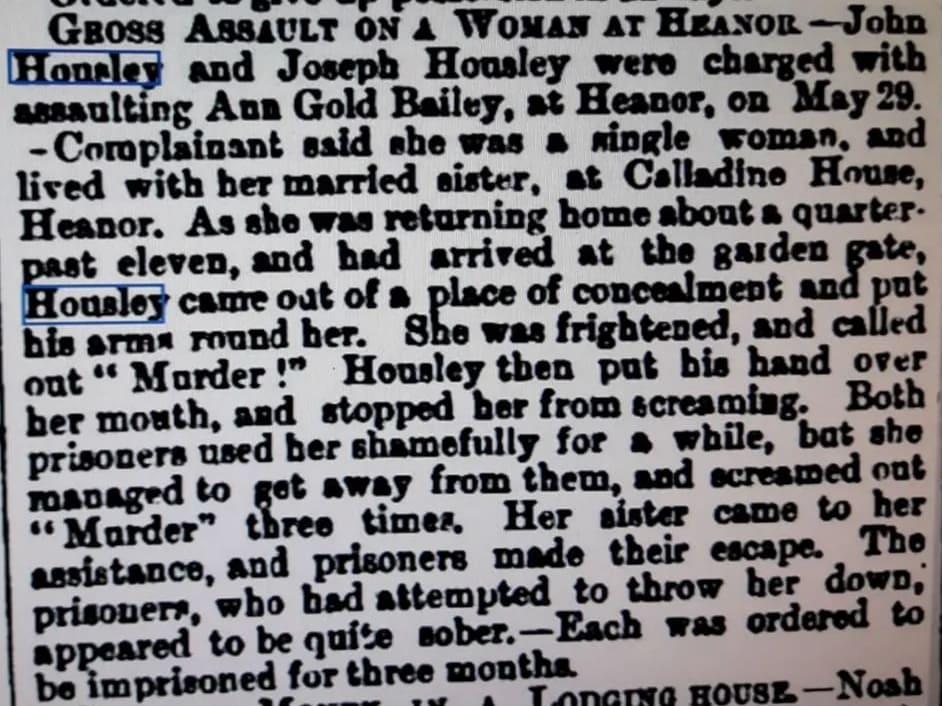

A mention of a John Housley of Heanor in the Nottinghma Journal 1875. I don’t know for sure if the John mentioned here is the brother John who Joseph describes above as behaving improperly to his wife. John Housley had a son Joseph, born in 1840, and John’s wife Sarah died in 1870.

In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

SAMUEL HOUSLEY 1816-

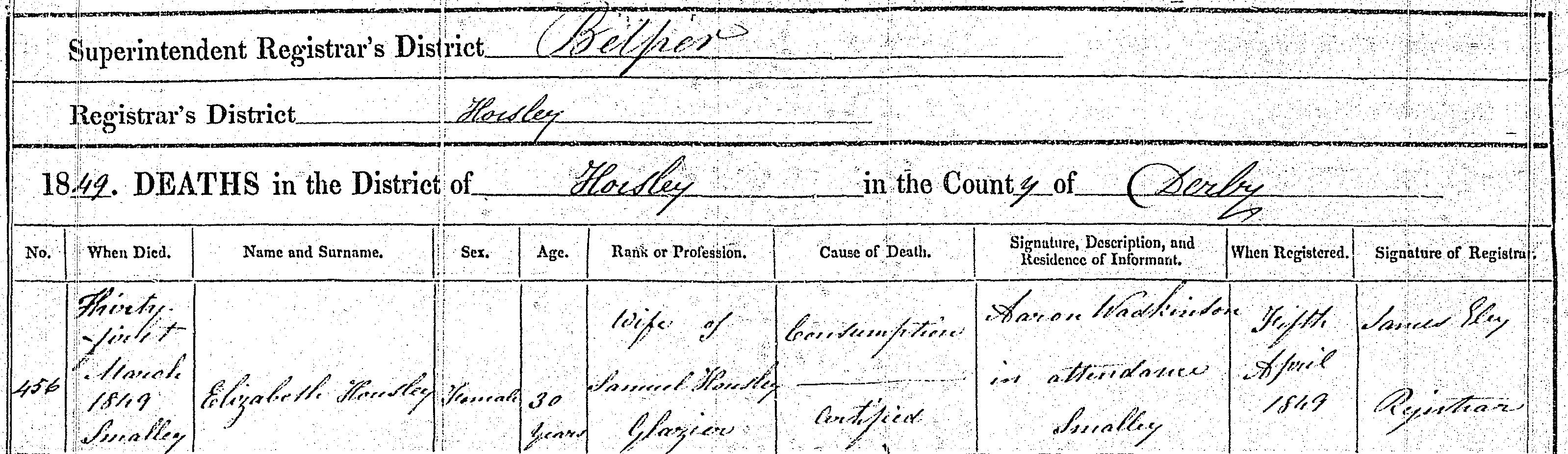

Sam married Elizabeth Brookes of Sutton Coldfield, and they had three daughters: Elizabeth, Mary Anne and Catherine. Elizabeth his wife died in 1849, a few months after Samuel’s father William died in 1848. The particular circumstances relating to these individuals have been discussed in previous chapters; the following are letter excerpts relating to them.

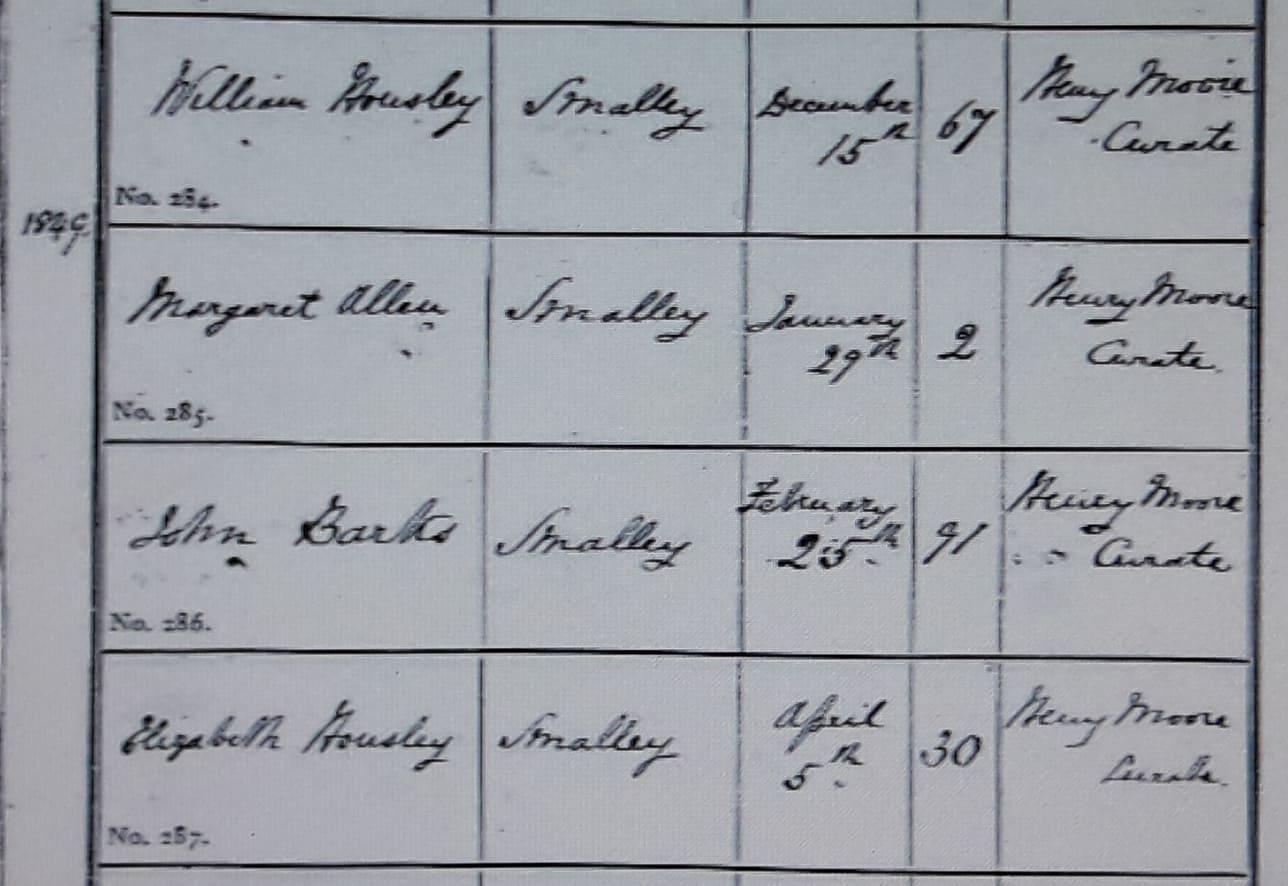

Death of William Housley 15 Dec 1848, and Elizabeth Housley 5 April 1849, Smalley:

Joseph wrote in December 1872: “I saw one of Sam’s daughters, the youngest Kate, you would remember her a baby I dare say. She is very comfortably married.”

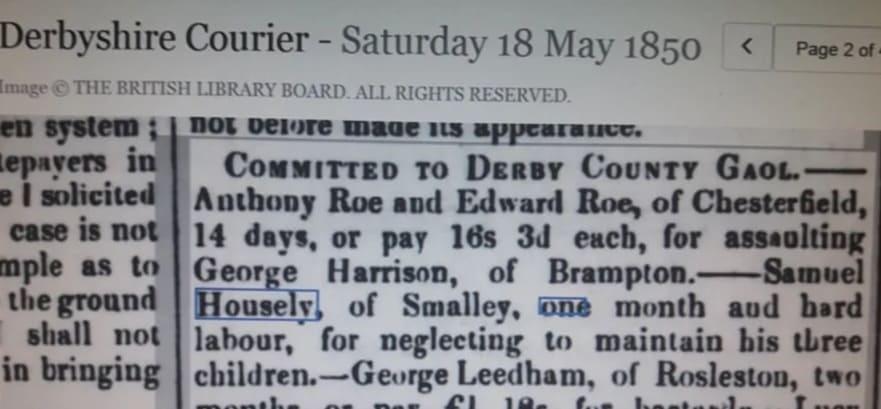

In the same letter (December 15, 1872), Joseph wrote: “I think we have now found all out now that is concerned in the matter for there was only Sam that we did not know his whereabouts but I was informed a week ago that he is dead–died about three years ago in Birmingham Union. Poor Sam. He ought to have come to a better end than that….His daughter and her husband went to Brimingham and also to Sutton Coldfield that is where he married his wife from and found out his wife’s brother. It appears he has been there and at Birmingham ever since he went away but ever fond of drink.”

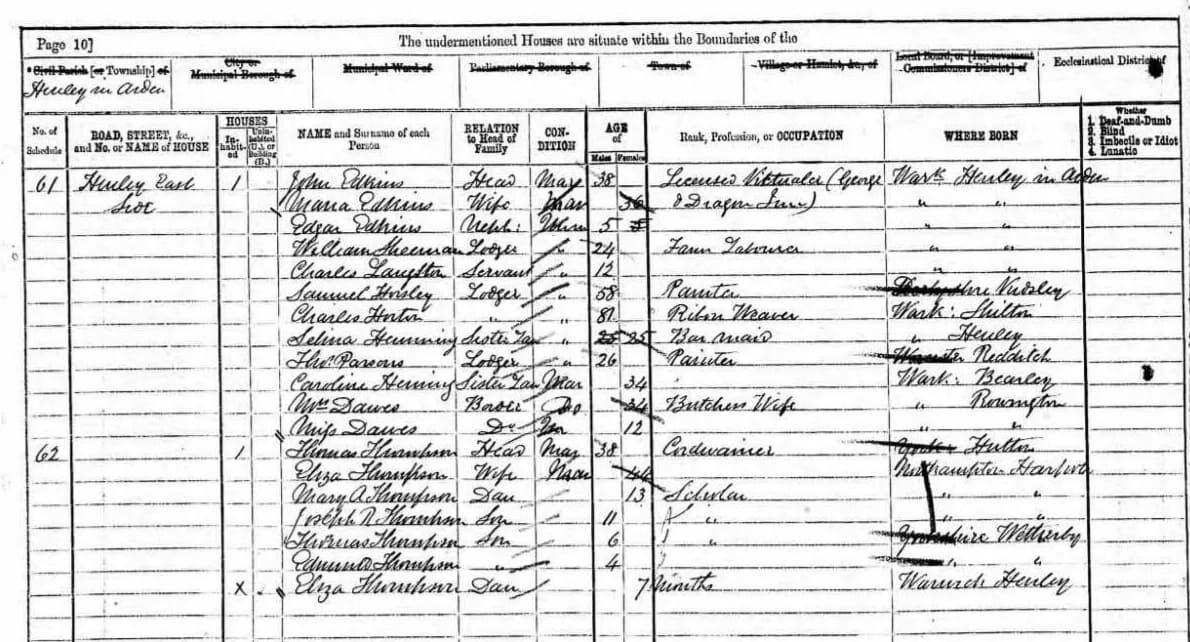

(Sam, however, was still alive in 1871, living as a lodger at the George and Dragon Inn, Henley in Arden. And no trace of Sam has been found since. It would appear that Sam did not want to be found.)

EDWARD HOUSLEY 1819-1843

Edward died before George left for USA in 1851, and as such there is no mention of him in the letters.

ANNE HOUSLEY 1821-1856

Anne wrote two letters to her brother George between February 1854 and her death in 1856. Apparently she suffered from a lung disease for she wrote: “I can say you will be surprised I am still living and better but still cough and spit a deal. Can do nothing but sit and sew.” According to the 1851 census, Anne, then 29, was a seamstress. Their friend, Mrs. Davy, wrote in March 1856: “This I send in a box to my Brother….The pincushion cover and pen wiper are Anne’s work–are for thy wife. She would have made it up had she been able.” Anne was not living at home at the time of the 1841 census. She would have been 19 or 20 and perhaps was “out service.”

In her second letter Anne wrote: “It is a great trouble now for me to write…as the body weakens so does the mind often. I have been very weak all summer. That I continue is a wonder to all and to spit so much although much better than when you left home.” She also wrote: “You know I had a desire for America years ago. Were I in health and strength, it would be the land of my adoption.”

In November 1855, Emma wrote, “Anne has been very ill all summer and has not been able to write or do anything.” Their neighbor Mrs. Davy wrote on March 21, 1856: “I fear Anne will not be long without a change.” In a black-edged letter the following June, Emma wrote: “I need not tell you how happy she was and how calmly and peacefully she died. She only kept in bed two days.”

Certainly Anne was a woman of deep faith and strong religious convictions. When she wrote that they were hoping to hear of Charles’ success on the gold fields she added: “But I would rather hear of him having sought and found the Pearl of great price than all the gold Australia can produce, (For what shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul?).” Then she asked George: “I should like to learn how it was you were first led to seek pardon and a savior. I do feel truly rejoiced to hear you have been led to seek and find this Pearl through the workings of the Holy Spirit and I do pray that He who has begun this good work in each of us may fulfill it and carry it on even unto the end and I can never doubt the willingness of Jesus who laid down his life for us. He who said whoever that cometh unto me I will in no wise cast out.”

Anne’s will was probated October 14, 1856. Mr. William Davy of Kidsley Park appeared for the family. Her estate was valued at under £20. Emma was to receive fancy needlework, a four post bedstead, feather bed and bedding, a mahogany chest of drawers, plates, linen and china. Emma was also to receive Anne’s writing desk. There was a condition that Ellen would have use of these items until her death.

The money that Anne was to receive from her grandfather, William Carrington, and her father, William Housley was to be distributed one third to Joseph, one third to Emma, and one third to be divided between her four neices: John’s daughter Elizabeth, 18, and Sam’s daughters Elizabeth, 10, Mary Ann, 9 and Catharine, age 7 to be paid by the trustees as they think “most useful and proper.” Emma Lyon and Elizabeth Davy were the witnesses.

The Carrington Farm:

CHARLES HOUSLEY 1823-1855

Charles went to Australia in 1851, and was last heard from in January 1853. According to the solicitor, who wrote to George on June 3, 1874, Charles had received advances on the settlement of their parent’s estate. “Your promissory note with the two signed by your brother Charles for 20 pounds he received from his father and 20 pounds he received from his mother are now in the possession of the court.”

Charles and George were probably quite close friends. Anne wrote in 1854: “Charles inquired very particularly in both his letters after you.”

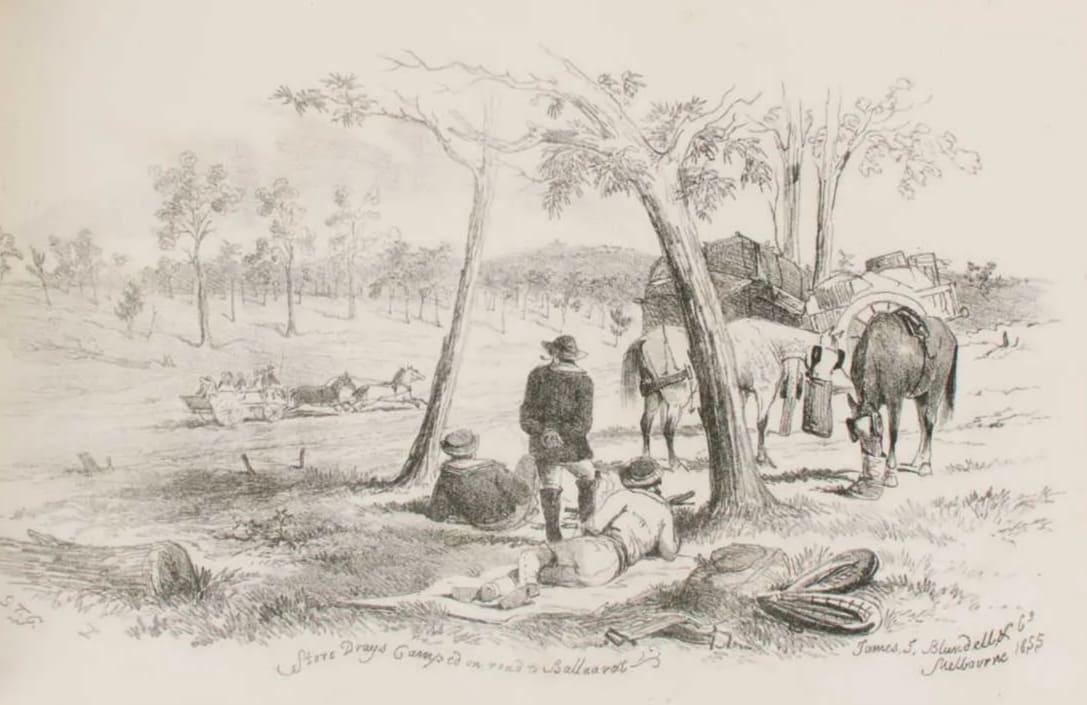

According to Anne, Charles and a friend married two sisters. He and his father-in-law had a farm where they had 130 cows and 60 pigs. Whatever the trade he learned in England, he never worked at it once he reached Australia. While it does not seem that Charles went to Australia because gold had been discovered there, he was soon caught up in “gold fever”. Anne wrote: “I dare say you have heard of the immense gold fields of Australia discovered about the time he went. Thousands have since then emigrated to Australia, both high and low. Such accounts we heard in the papers of people amassing fortunes we could not believe. I asked him when I wrote if it was true. He said this was no exaggeration for people were making their fortune daily and he intended going to the diggings in six weeks for he could stay away no longer so that we are hoping to hear of his success if he is alive.”

In March 1856, Mrs. Davy wrote: “I am sorry to tell thee they have had a letter from Charles’s wife giving account of Charles’s death of 6 months consumption at the Victoria diggings. He has left 2 children a boy and a girl William and Ellen.” In June of the same year in a black edged letter, Emma wrote: “I think Mrs. Davy mentioned Charles’s death in her note. His wife wrote to us. They have two children Helen and William. Poor dear little things. How much I should like to see them all. She writes very affectionately.”

In December 1872, Joseph wrote: “I’m told that Charles two daughters has wrote to Smalley post office making inquiries about his share….” In January 1876, the solicitor wrote: “Charles Housley’s children have claimed their father’s share.”

GEORGE HOUSLEY 1824-1877

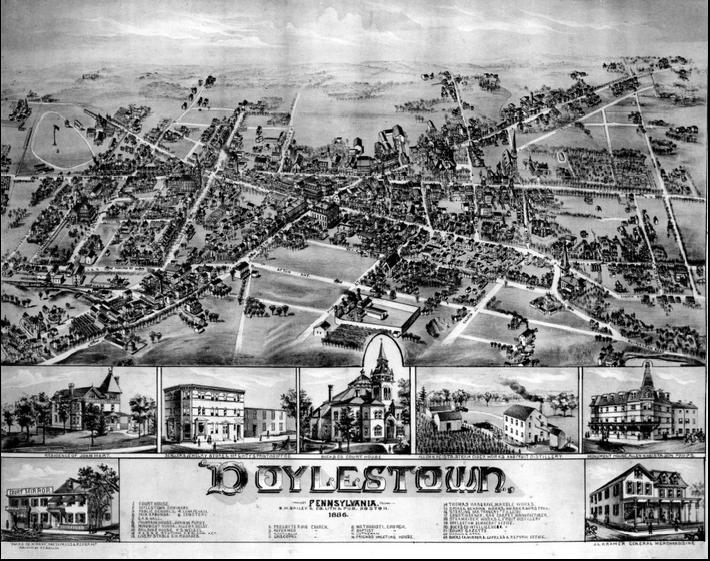

George emigrated to the United states in 1851, arriving in July. The solicitor Abraham John Flint referred in a letter to a 15-pound advance which was made to George on June 9, 1851. This certainly was connected to his journey. George settled along the Delaware River in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The letters from the solicitor were addressed to: Lahaska Post Office, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

George married Sarah Ann Hill on May 6, 1854 in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. In her first letter (February 1854), Anne wrote: “We want to know who and what is this Miss Hill you name in your letter. What age is she? Send us all the particulars but I would advise you not to get married until you have sufficient to make a comfortable home.”

Upon learning of George’s marriage, Anne wrote: “I hope dear brother you may be happy with your wife….I hope you will be as a son to her parents. Mother unites with me in kind love to you both and to your father and mother with best wishes for your health and happiness.” In 1872 (December) Joseph wrote: “I am sorry to hear that sister’s father is so ill. It is what we must all come to some time and hope we shall meet where there is no more trouble.”

Emma wrote in 1855, “We write in love to your wife and yourself and you must write soon and tell us whether there is a little nephew or niece and what you call them.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “We want to see dear Sarah Ann and the dear little boy. We were much pleased with the “bit of news” you sent.” The bit of news was the birth of John Eley Housley, January 11, 1855. Emma concluded her letter “Give our very kindest love to dear sister and dearest Johnnie.”

In September 1872, Joseph wrote, “I was very sorry to hear that John your oldest had met with such a sad accident but I hope he is got alright again by this time.” In the same letter, Joseph asked: “Now I want to know what sort of a town you are living in or village. How far is it from New York? Now send me all particulars if you please.”

In March 1873 Harriet asked Sarah Ann: “And will you please send me all the news at the place and what it is like for it seems to me that it is a wild place but you must tell me what it is like….”. The question of whether she was referring to Bucks County, Pennsylvania or some other place is raised in Joseph’s letter of the same week.

On March 17, 1873, Joseph wrote: “I was surprised to hear that you had gone so far away west. Now dear brother what ever are you doing there so far away from home and family–looking out for something better I suppose.”The solicitor wrote on May 23, 1874: “Lately I have not written because I was not certain of your address and because I doubted I had much interesting news to tell you.” Later, Joseph wrote concerning the problems settling the estate, “You see dear brother there is only me here on our side and I cannot do much. I wish you were here to help me a bit and if you think of going for another summer trip this turn you might as well run over here.”

Apparently, George had indicated he might return to England for a visit in 1856. Emma wrote concerning the portrait of their mother which had been sent to George: “I hope you like mother’s portrait. I did not see it but I suppose it was not quite perfect about the eyes….Joseph and I intend having ours taken for you when you come over….Do come over before very long.”

In March 1873, Joseph wrote: “You ask me what I think of you coming to England. I think as you have given the trustee power to sign for you I think you could do no good but I should like to see you once again for all that. I can’t say whether there would be anything amiss if you did come as you say it would be throwing good money after bad.”

On June 10, 1875, the solicitor wrote: “I have been expecting to hear from you for some time past. Please let me hear what you are doing and where you are living and how I must send you your money.” George’s big news at that time was that on May 3, 1875, he had become a naturalized citizen “renouncing and abjuring all allegiance and fidelity to every foreign prince, potentate, state and sovereignity whatsoever, and particularly to Victoria Queen of Great Britain of whom he was before a subject.”

ROBERT HOUSLEY 1832-1851

In 1854, Anne wrote: “Poor Robert. He died in August after you left he broke a blood vessel in the lung.”

From Joseph’s first letter we learn that Robert was 19 when he died: “Dear brother there have been a great many changes in the family since you left us. All is gone except myself and John and Sam–we have heard nothing of him since he left. Robert died first when he was 19 years of age. Then Anne and Charles too died in Australia and then a number of years elapsed before anyone else. Then John lost his wife, then Emma, and last poor dear mother died last January on the 11th.”Anne described Robert’s death in this way: “He had thrown up blood many times before in the spring but the last attack weakened him that he only lived a fortnight after. He died at Derby. Mother was with him. Although he suffered much he never uttered a murmur or regret and always a smile on his face for everyone that saw him. He will be regretted by all that knew him”.

Robert died a resident of St. Peter’s Parish, Derby, but was buried in Smalley on August 16, 1851.

Apparently Robert was apprenticed to be a joiner for, according to Anne, Joseph took his place: “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after and is there still.”In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

EMMA HOUSLEY 1836-1871

Emma was not mentioned in Anne’s first letter. In the second, Anne wrote that Emma was living at Spondon with two ladies in her “third situation,” and added, “She is grown a bouncing woman.” Anne described her sister well. Emma wrote in her first letter (November 12, 1855): “I must tell you that I am just 21 and we had my pudding last Sunday. I wish I could send you a piece.”

From Emma’s letters we learn that she was living in Derby from May until November 1855 with Mr. Haywood, an iron merchant. She explained, “He has failed and I have been obliged to leave,” adding, “I expect going to a new situation very soon. It is at Belper.” In 1851 records, William Haywood, age 22, was listed as an iron foundry worker. In the 1857 Derby Directory, James and George were listed as iron and brass founders and ironmongers with an address at 9 Market Place, Derby.

In June 1856, Emma wrote from “The Cedars, Ashbourne Road” where she was working for Mr. Handysides.

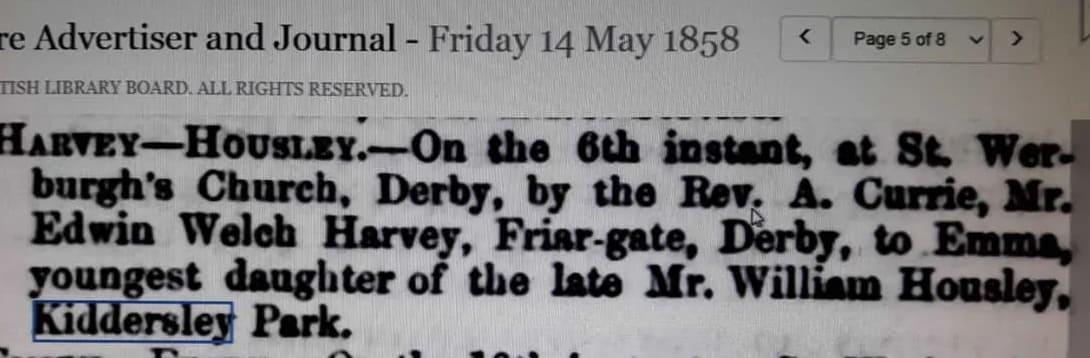

While she was working for Mr. Handysides, Emma wrote: “Mother is thinking of coming to live at Derby. That will be nice for Joseph and I.”Friargate and Ashbourne Road were located in St. Werburgh’s Parish. (In fact, St. Werburgh’s vicarage was at 185 Surrey Street. This clue led to the discovery of the record of Emma’s marriage on May 6, 1858, to Edwin Welch Harvey, son of Samuel Harvey in St. Werburgh’s.)

In 1872, Joseph wrote: “Our sister Emma, she died at Derby at her own home for she was married. She has left two young children behind. The husband was the son of the man that I went apprentice to and has caused a great deal of trouble to our family and I believe hastened poor Mother’s death….”. Joseph added that he believed Emma’s “complaint” was consumption and that she was sick a good bit. Joseph wrote: “Mother was living with John when I came home (from Ascension Island around 1867? or to Smalley from Derby around 1870?) for when Emma was married she broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby did not agree with her so she had to leave it again but left all her things there.”

Emma Housley and Edwin Welch Harvey wedding, 1858:

JOSEPH HOUSLEY 1838-1893

We first hear of Joseph in a letter from Anne to George in 1854. “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after (probably 1851) and is there still. He is grown as tall as you I think quite a man.” Emma concurred in her first letter: “He is quite a man in his appearance and quite as tall as you.”

From Emma we learn in 1855: “Joseph has left Mr. Harvey. He had not work to employ him. So mother thought he had better leave his indenture and be at liberty at once than wait for Harvey to be a bankrupt. He has got a very good place of work now and is very steady.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote “Joseph and I intend to have our portraits taken for you when you come over….Mother is thinking of coming to Derby. That will be nice for Joseph and I. Joseph is very hearty I am happy to say.”

According to Joseph’s letters, he was married to Harriet Ballard. Joseph described their miraculous reunion in this way: “I must tell you that I have been abroad myself to the Island of Ascension. (Elsewhere he wrote that he was on the island when the American civil war broke out). I went as a Royal Marine and worked at my trade and saved a bit of money–enough to buy my discharge and enough to get married with but while I was out on the island who should I meet with there but my dear wife’s sister. (On two occasions Joseph and Harriet sent George the name and address of Harriet’s sister, Mrs. Brooks, in Susquehanna Depot, Pennsylvania, but it is not clear whether this was the same sister.) She was lady’s maid to the captain’s wife. Though I had never seen her before we got to know each other somehow so from that me and my wife recommenced our correspondence and you may be sure I wanted to get home to her. But as soon as I did get home that is to England I was not long before I was married and I have not regretted yet for we are very comfortable as well as circumstances will allow for I am only a journeyman joiner.”

Proudly, Joseph wrote: “My little family consists of three nice children–John, Joseph and Susy Annie.” On her birth certificate, Susy Ann’s birthdate is listed as 1871. Parish records list a Lucy Annie christened in 1873. The boys were born in Derby, John in 1868 and Joseph in 1869. In his second letter, Joseph repeated: “I have got three nice children, a good wife and I often think is more than I have deserved.” On August 6, 1873, Joseph and Harriet wrote: “We both thank you dear sister for the pieces of money you sent for the children. I don’t know as I have ever see any before.” Joseph ended another letter: “Now I must close with our kindest love to you all and kisses from the children.”

In Harriet’s letter to Sarah Ann (March 19, 1873), she promised: “I will send you myself and as soon as the weather gets warm as I can take the children to Derby, I will have them taken and send them, but it is too cold yet for we have had a very cold winter and a great deal of rain.” At this time, the children were all under 6 and the baby was not yet two.

In March 1873 Joseph wrote: “I have been working down at Heanor gate there is a joiner shop there where Kings used to live I have been working there this winter and part of last summer but the wages is very low but it is near home that is one comfort.” (Heanor Gate is about 1/4 mile from Kidsley Grange. There was a school and industrial park there in 1988.) At this time Joseph and his family were living in “the big house–in Old Betty Hanson’s house.” The address in the 1871 census was Smalley Lane.

A glimpse into Joseph’s personality is revealed by this remark to George in an 1872 letter: “Many thanks for your portrait and will send ours when we can get them taken for I never had but one taken and that was in my old clothes and dear Harriet is not willing to part with that. I tell her she ought to be satisfied with the original.”

On one occasion Joseph and Harriet both sent seeds. (Marks are still visible on the paper.) Joseph sent “the best cow cabbage seed in the country–Robinson Champion,” and Harriet sent red cabbage–Shaw’s Improved Red. Possibly cow cabbage was also known as ox cabbage: “I hope you will have some good cabbages for the Ox cabbage takes all the prizes here. I suppose you will be taking the prizes out there with them.” Joseph wrote that he would put the name of the seeds by each “but I should think that will not matter. You will tell the difference when they come up.”

George apparently would have liked Joseph to come to him as early as 1854. Anne wrote: “As to his coming to you that must be left for the present.” In 1872, Joseph wrote: “I have been thinking of making a move from here for some time before I heard from you for it is living from hand to mouth and never certain of a job long either.” Joseph then made plans to come to the United States in the spring of 1873. “For I intend all being well leaving England in the spring. Many thanks for your kind offer but I hope we shall be able to get a comfortable place before we have been out long.” Joseph promised to bring some things George wanted and asked: “What sort of things would be the best to bring out there for I don’t want to bring a lot that is useless.” Joseph’s plans are confirmed in a letter from the solicitor May 23, 1874: “I trust you are prospering and in good health. Joseph seems desirous of coming out to you when this is settled.”

George must have been reminiscing about gooseberries (Heanor has an annual gooseberry show–one was held July 28, 1872) and Joseph promised to bring cuttings when they came: “Dear Brother, I could not get the gooseberries for they was all gathered when I received your letter but we shall be able to get some seed out the first chance and I shall try to bring some cuttings out along.” In the same letter that he sent the cabbage seeds Joseph wrote: “I have got some gooseberries drying this year for you. They are very fine ones but I have only four as yet but I was promised some more when they were ripe.” In another letter Joseph sent gooseberry seeds and wrote their names: Victoria, Gharibaldi and Globe.

In September 1872 Joseph wrote; “My wife is anxious to come. I hope it will suit her health for she is not over strong.” Elsewhere Joseph wrote that Harriet was “middling sometimes. She is subject to sick headaches. It knocks her up completely when they come on.” In December 1872 Joseph wrote, “Now dear brother about us coming to America you know we shall have to wait until this affair is settled and if it is not settled and thrown into Chancery I’m afraid we shall have to stay in England for I shall never be able to save money enough to bring me out and my family but I hope of better things.”

On July 19, 1875 Abraham Flint (the solicitor) wrote: “Joseph Housley has removed from Smalley and is working on some new foundry buildings at Little Chester near Derby. He lives at a village called Little Eaton near Derby. If you address your letter to him as Joseph Housley, carpenter, Little Eaton near Derby that will no doubt find him.”

George did not save any letters from Joseph after 1874, hopefully he did reach him at Little Eaton. Joseph and his family are not listed in either Little Eaton or Derby on the 1881 census.

In his last letter (February 11, 1874), Joseph sounded very discouraged and wrote that Harriet’s parents were very poorly and both had been “in bed for a long time.” In addition, Harriet and the children had been ill.

The move to Little Eaton may indicate that Joseph received his settlement because in August, 1873, he wrote: “I think this is bad news enough and bad luck too, but I have had little else since I came to live at Kiddsley cottages but perhaps it is all for the best if one could only think so. I have begun to think there will be no chance for us coming over to you for I am afraid there will not be so much left as will bring us out without it is settled very shortly but I don’t intend leaving this house until it is settled either one way or the other. “Joseph Housley and the Kiddsley cottages:

January 14, 2022 at 7:27 am #6252

January 14, 2022 at 7:27 am #6252In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The USA Housley’s

This chapter is copied from Barbara Housley’s Narrative on Historic Letters, with thanks to her brother Howard Housley for sharing it with me. Interesting to note that Housley descendants (on the Marshall paternal side) and Gretton descendants (on the Warren maternal side) were both living in Trenton, New Jersey at the same time.

GEORGE HOUSLEY 1824-1877

George emigrated to the United states in 1851, arriving in July. The solicitor Abraham John Flint referred in a letter to a 15-pound advance which was made to George on June 9, 1851. This certainly was connected to his journey. George settled along the Delaware River in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The letters from the solicitor were addressed to: Lahaska Post Office, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. George married Sarah Ann Hill on May 6, 1854 in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The service was performed by Attorney James Gilkyson.

In her first letter (February 1854), Anne (George’s sister in Smalley, Derbyshire) wrote: “We want to know who and what is this Miss Hill you name in your letter. What age is she? Send us all the particulars but I would advise you not to get married until you have sufficient to make a comfortable home.”

Upon learning of George’s marriage, Anne wrote: “I hope dear brother you may be happy with your wife….I hope you will be as a son to her parents. Mother unites with me in kind love to you both and to your father and mother with best wishes for your health and happiness.” In 1872 (December) Joseph (George’s brother) wrote: “I am sorry to hear that sister’s father is so ill. It is what we must all come to some time and hope we shall meet where there is no more trouble.”

Emma (George’s sister) wrote in 1855, “We write in love to your wife and yourself and you must write soon and tell us whether there is a little nephew or niece and what you call them.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “We want to see dear Sarah Ann and the dear little boy. We were much pleased with the “bit of news” you sent.” The bit of news was the birth of John Eley Housley, January 11, 1855. Emma concluded her letter “Give our very kindest love to dear sister and dearest Johnnie.”

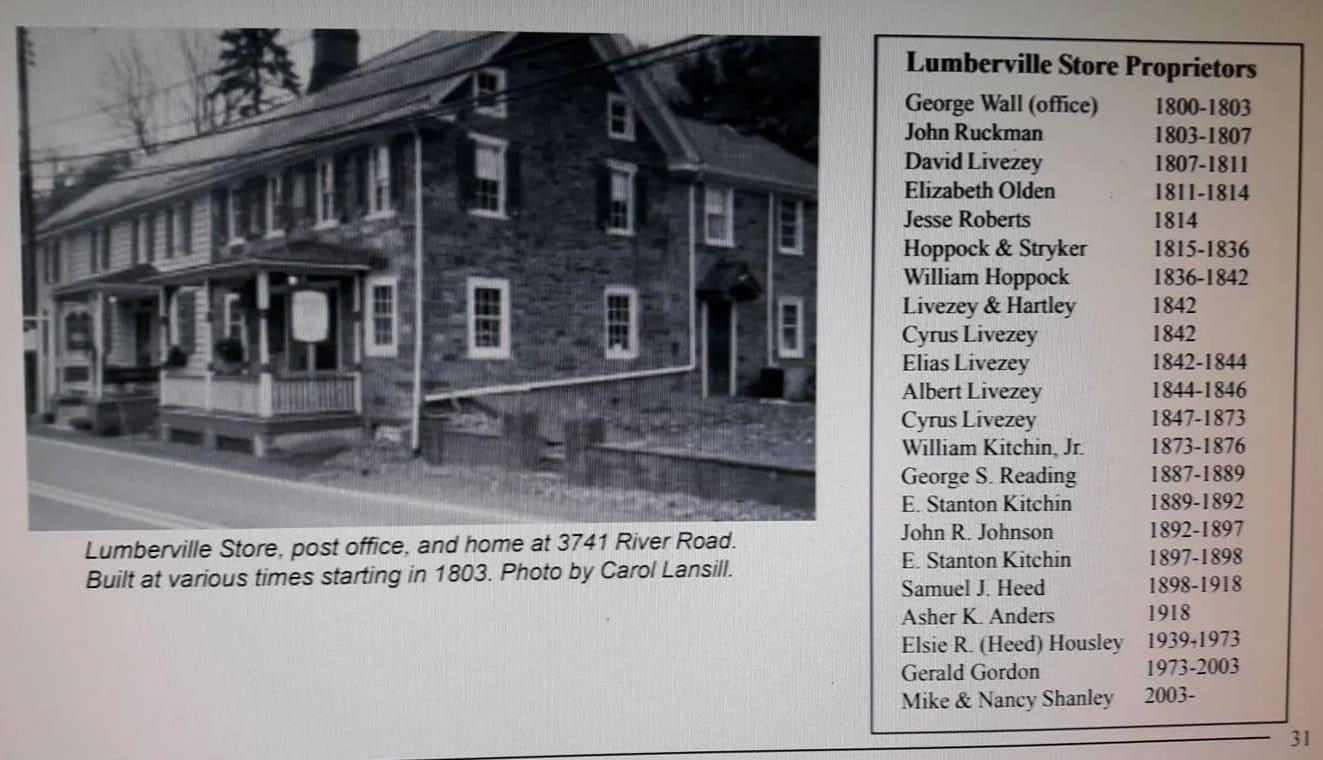

According to his obituary, John Eley was born at Wrightstown and “removed” to Lumberville at the age of 19. John was married first to Lucy Wilson with whom he had three sons: George Wilson (1883), Howard (1893) and Raymond (1895); and then to Elizabeth Kilmer with whom he had one son Albert Kilmer (1907). John Eley Housley died November 20, 1926 at the age of 71. For many years he had worked for John R. Johnson who owned a store. According to his son Albert, John was responsible for caring for Johnson’s horses. One named Rex was considered to be quite wild, but was docile in John’s hands. When John would take orders, he would leave the wagon at the first house and walk along the backs of the houses so that he would have access to the kitchens. When he reached the seventh house he would climb back over the fence to the road and whistle for the horses who would come to meet him. John could not attend church on Sunday mornings because he was working with the horses and occasionally Albert could convince his mother that he was needed also. According to Albert, John was regular in attendance at church on Sunday evenings.

John was a member of the Carversville Lodge 261 IOOF and the Carversville Lodge Knights of Pythias. Internment was in the Carversville cemetery; not, however, in the plot owned by his father. In addition to his sons, he was survived by his second wife Elizabeth who lived to be 80 and three grandchildren: George’s sons, Kenneth Worman and Morris Wilson and Raymond’s daughter Miriam Louise. George had married Katie Worman about the time John Eley married Elizabeth Kilmer. Howard’s first wife Mary Brink and daughter Florence had died and he remarried Elsa Heed who also lived into her eighties. Raymond’s wife was Fanny Culver.

Two more sons followed: Joseph Sackett, who was known as Sackett, September 12, 1856 and Edwin or Edward Rose, November 11, 1858. Joseph Sackett Housley married Anna Hubbs of Plumsteadville on January 17, 1880. They had one son Nelson DeC. who in turn had two daughters, Eleanor Mary and Ruth Anna, and lived on Bert Avenue in Trenton N.J. near St. Francis Hospital. Nelson, who was an engineer and built the first cement road in New Jersey, died at the age of 51. His daughters were both single at the time of his death. However, when his widow, the former Eva M. Edwards, died some years later, her survivors included daughters, Mrs. Herbert D. VanSciver and Mrs. James J. McCarrell and four grandchildren. One of the daughters (the younger) was quite crippled in later years and would come to visit her great-aunt Elizabeth (John’s widow) in a chauffeur driven car. Sackett died in 1929 at the age of 70. He was a member of the Warrington Lodge IOOF of Jamison PA, the Uncas tribe and the Uncas Hayloft 102 ORM of Trenton, New Jersey. The interment was in Greenwood cemetery where he had been caretaker since his retirement from one of the oldest manufacturing plants in Trenton (made milk separators for one thing). Sackett also was the caretaker for two other cemeteries one located near the Clinton Street station and the other called Riverside.