-

AuthorSearch Results

-

March 28, 2025 at 10:28 pm #7881

In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Mars Outpost — Welcome to the Wild Wild Waste

No one had anticipated how long it would take to get a shuttle full of half-motivated, gravity-averse Helix25 passengers to agree on proper footwear.

“I told you, Claudius, this is the fancy terrain suit. The others make my hips look like reinforced cargo crates,” protested Tilly Nox, wrangling with her buckles near the shuttle airlock.

“You’re about to step onto a red-rock planet that hasn’t seen visitors since the Asteroid Belt Mining Fiasco,” muttered Claudius, tightening his helmet strap. “Your hips are the least of Mars’ concerns.”

Behind them, a motley group of Helix25 residents fidgeted with backpacks, oxygen readouts, and wide-eyed anticipation. Veranassessee had allowed a single-day “expedition excursion” for those eager—or stir-crazy—enough to brave Mars’ surface. She’d made it clear it was volunteer-only.

Most stayed aboard, in orbit of the red planet, looking at its surface from afar to the tune of “eh, gravity, don’t we have enough of that here?” —Finkley had recoiled in horror at the thought of real dust getting through the vents and had insisted on reviewing personally all the airlocks protocols. No way that they’d sullied her pristine halls with Martian dust or any dust when the shuttle would come back. No – way.

But for the dozen or so who craved something raw and unfiltered, this was it. Mars: the myth, the mirage, the Far West frontier at the invisible border separating Earthly-like comforts into the wider space without any safety net.

At the helm of Shuttle Dandelion, Sue Forgelot gave the kind of safety briefing that could both terrify and inspire. “If your oxygen starts blinking red, panic quietly and alert your buddy. If you fall into a crater, forget about taking a selfie, wave your arms and don’t grab on your neighbor. And if you see a sand wyrm, congratulations, you’ve either hit gold or gone mad.”

Luca Stroud chuckled from the copilot seat. “Didn’t see you so chirpy in a long while. That kind of humour, always the best warning label.”

They touched down near Outpost Station Delta-6 just as the Martian wind was picking up, sending curls of red dust tumbling like gossip.

And there she was.

Leaning against the outpost hatch with a spanner slung across one shoulder, goggles perched on her forehead, Prune watched them disembark with the wary expression of someone spotting tourists traipsing into her backyard garden.

Sue approached first, grinning behind her helmet. “Prune Curara, I presume?”

“You presume correctly,” she said, arms crossed. “Let me guess. You’re here to ruin my peace and use my one functioning kettle.”

Luca offered a warm smile. “We’re only here for a brief scan and a bit of radioactive treasure hunting. Plus, apparently, there’s been a petition to name a Martian dust lizard after you.”

“That lizard stole my solar panel last year,” Prune replied flatly. “It deserves no honor.”

Inside, the outpost was cramped, cluttered, and undeniably charming. Hand-drawn maps of Martian magnetic hotspots lined one wall; shelves overflowed with tagged samples, sketchpads, half-disassembled drones, and a single framed photo of a fireplace with something hovering inexplicably above it—a fish?

“Flying Fish Inn,” Luca whispered to Sue. “Legendary.”

The crew spent the day fanning out across the region in staggered teams. Sue and Claudius oversaw the scan points, Tilly somehow got her foot stuck in a crevice that definitely wasn’t in the geological briefing, which was surprisingly enough about as much drama they could conjure out.

Back at the outpost, Prune fielded questions, offered dry warnings, and tried not to get emotionally attached to the odd, bumbling crew now walking through her kingdom.

Then, near sunset, Veranassessee’s voice crackled over comms: “Curara. We’ll be lifting a crew out tomorrow, but leaving a team behind. With the right material, for all the good Muck’s mining expedition did out on the asteroid belt, it left the red planet riddled with precious rocks. But you, you’ve earned to take a rest, with a ticket back aboard. That’s if you want it. Three months back to Earth via the porkchop plot route. No pressure. Your call.”

Prune froze. Earth.

The word sat like an old song on her tongue. Faint. Familiar. Difficult to place.

She stepped out to the ridge, watching the sun dip low across the dusty plain. Behind her, laughter from the tourists trading their stories of the day —Tilly had rigged a heat plate with steel sticks and somehow convinced people to roast protein foam. Are we wasting oxygen now? Prune felt a weight lift; after such a long time struggling to make ends meet, she now could be free of that duty.

Prune closed her eyes. In her head, Mater’s voice emerged, raspy and amused: You weren’t meant to settle, sugar. You were meant to stir things up. Even on Mars.

She let the words tumble through her like sand in her boots.

She’d conquered her dream, lived it, thrived in it.

Now people were landing, with their new voices, new messes, new puzzles.

She could stay. Be the last queen of red rock and salvaged drones.

Or she could trade one hell of people for another. Again.

The next morning, with her patched duffel packed and goggles perched properly this time, Prune boarded Shuttle Dandelion with a half-smirk and a shrug.

“I’m coming,” she told Sue. “Can’t let Earth ruin itself again without at least watching.”

Sue grinned. “Welcome back to the madhouse.”

As the shuttle lifted off, Prune looked once, just once, at the red plains she’d called home.

“Thanks, Mars,” she whispered. “Don’t wait up.”

February 23, 2025 at 1:42 pm #7829In reply to: Helix Mysteries – Inside the Case

Helix 25 – Investigation Breakdown: Suspects, Factions, and Ship’s Population

To systematically investigate the murder(s) and the overarching mystery, let’s break down the known groups and individuals, their possible means to commit crimes, and their potential motivations.

1. Ship Population & Structure

Estimated Population of Helix 25

- Originally a luxury cruise ship before the exodus.

- Largest cruise ships built on Earth in 2025 carried ~5,000 people.

Space travel, however, requires generations. - Estimated current ship population on Helix 25: Between 15,000 and 50,000, depending on deck expansion and growth of refugee populations over decades.

- Possible Ship Propulsion:

- Plasma-based propulsion (high-efficiency ion drives)

- Slingshot navigation using gravity assists

- Solar sails & charged particle fields

- Current trajectory: Large elliptical orbit, akin to a comet.

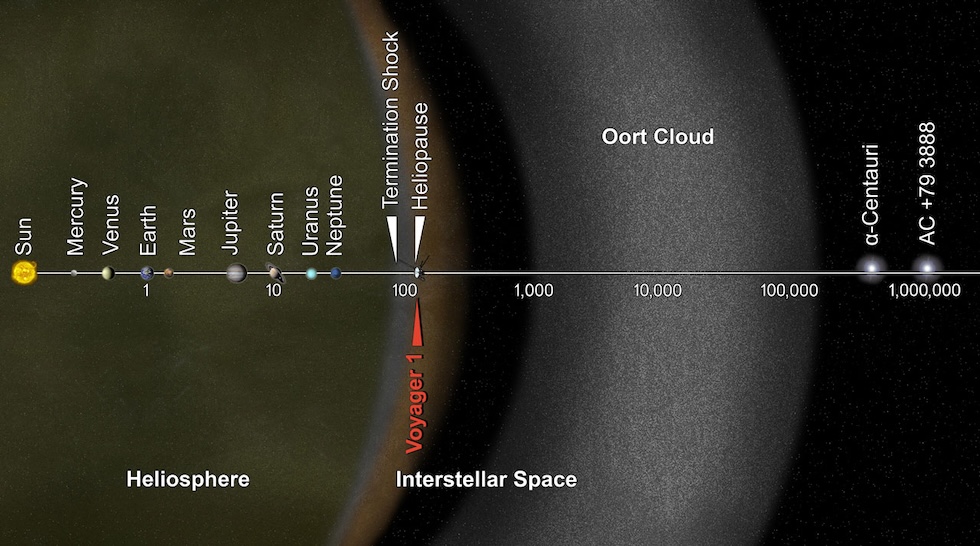

Estimated direction of the original space trek was still within Solar System, not beyond the Kuiper Belt (~30 astrological units) and programmed to return towards it point of origin.

Due to the reprogramming by the refugees, it is not known if there has been significant alteration of the course – it should be known as the ship starts to reach the aphelion (farthest from the Sun) and either comes back towards it, or to a different course.

- Question: Are they truly on a course out of the galaxy? Or is that just the story Synthia is feeding them?

Is there a Promised Land beyond the Ark’s adventure?

2. Breaking Down People & Factions

To find the killer(s), conspiracies, and ship dynamics, here are some of factions, known individuals, and their possible means/motives.

A. Upper Decks: The Elite & Decision-Makers

- Defining Features:

- Wealthy descendants of the original passengers. They have adopted names of stars as new family names, as if de-facto rulers of the relative segments of the space.

- Have never known hardship like the Lower Decks.

- Kept busy with social prestige, arts, and “meaningful” pursuits to prevent existential crisis.

Key Individuals:

-

- Means: Extensive social connections, influence, and hidden cybernetic enhancements.

- Motive: Could be protecting something or someone—she knows too much about the ship’s past.

- Secrets: Claims to have met the Captain. Likely lying… unless?

-

- Means: Expert geneticist, access to data. Could tamper with DNA.

- Motive: What if Herbert knew something about her old research? Did she kill to bury it?

-

Ellis Marlowe (Retired Postman) –

- Means: None obvious. But as a former Earth liaison, he has archives and knowledge of what was left behind.

- Motive: Unclear, but his son was the murder victim. His son was previously left on Earth, and seemed to have found a way onto Helix 25 (possibly through the refugee wave who took over the ship)

- Question: Did he know Herbert’s real identity?

-

Finkley (Upper Deck cleaner, informant) –

- Means: As a cleaner, has access everywhere.

- Motive: None obvious, but cleaners notice everything.

- Secret: She and Finja (on Earth) are telepathically linked. Could Finja have picked up something?

-

The Three Old Ladies (Shar, Glo, Mavis) –

- Means: Absolutely none.

- Motive: Probably just want more drama.

- Accidental Detectives: They mix up stories but might have stumbled on actual facts.

-

Trevor Pee Marshall (TP, AI detective) –

- Means: Can scan records, project into locations, analyze logic patterns.

- Motive: Should have none—unless he’s been compromised as hinted by some of the remnants of old Muck & Lump tech into his program.

B. Lower Decks: Workers, Engineers, Hidden Knowledge

- Defining Features:

- Unlike the Upper Decks, they work—mechanics, hydroponics, labor.

- Self-sufficient, but cut off from decisions.

- Some distrust Synthia, believing Helix 25 is off-course.

Key Individuals:

-

Luca Stroud (Engineer, Cybernetic Expert) –

- Means: Can tamper with ship’s security, medical implants, and life-support systems.

- Motive: Possible sabotage, or he was helping Herbert with something.

- Secret: Works in black-market tech modifications.

-

Romualdo (Gardener, Archivist-in-the-Making) –

- Means: None obvious. Seem to lack the intelligence, but isn’t stupid.

- Motive: None—but he lent Herbert a Liz Tattler book about genetic memories.

- Question: What exactly did Herbert learn from his reading?

-

Zoya Kade (Revolutionary Figure, Not Directly Involved) –

- Means: Strong ideological influence, but not an active conspirator.

- Motive: None, but her teachings have created and fed factions.

-

The Underground Movement –

- Means: They know ways around Synthia’s surveillance.

- Motive: They believe the ship is on a suicide mission.

- Question: Would they kill to prove it?

C. The Hold: The Wild Cards & Forgotten Spaces

- Defining Features:

- Refugees who weren’t fully integrated.

- Maintain autonomy, trade, and repair systems that the rest of the ship ignores.

Key Individuals:

-

Kai Nova (Pilot, Disillusioned) –

- Means: Can manually override ship systems… if Synthia lets him.

- Motive: Suspects something’s off about the ship’s fuel levels.

-

Cadet Taygeta (Sharp, Logical, Too Honest) –

- Means: No real power, but access to data.

- Motive: Trying to figure out what Kai is hiding.

D. AI & Non-Human Factors

-

Synthia (Central AI, Overseer of Helix 25)

- Means: Controls everything.

- Motive: Unclear, but her instructions are decades old.

- Question: Does she even have free will?

-

The Captain (Nemo)

- Means: Access to ship-wide controls. He is blending in the ship’s population but has special access.

- Motive: Seems uncertain about his mission.

- Secret: He might not be following Synthia’s orders anymore.

3. Who Has the Means to Kill in Zero-G?

The next murder happens in a zero-gravity sector. Likely methods:

- Oxygen deprivation (tampered life-support, “accident”)

- Drowning (hydro-lab “malfunction”)

Likely Suspects for Next Murder

Suspect Means to Kill in Zero-G Motive Luca Stroud Can tamper with tech Knows ship secrets Amara Voss Access to medical, genetic data Herbert was digging into past Underground Movement Can evade Synthia’s surveillance Wants to prove ship is doomed Synthia (or Rogue AI processes) Controls airflow, gravity, and safety protocols If she sees someone as a threat, can she remove them? The Captain (Nemo?) Has override authority Is he protecting secrets?

4. Next Steps in the Investigation

- Evie and Riven Re-interview Suspects. Who benefited from Herbert’s death?

- Investigate the Flat-Earth Conspiracies. Who is spreading paranoia?

- Check the Captain’s Logs. What does Nemo actually believe?

- Stop the Next Murder. (Too late?)

Final Question: Where Do We Start?

- Evie and Riven visit the Captain’s quarters? (If they find him…)

- Investigate the Zero-G Crime Scene? (Second body = New urgency)

- Confront one of the Underground Members? (Are they behind it?)

Let’s pick a thread and dive back into the case!

February 3, 2025 at 7:54 am #7731In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

The colours were bright, garish really, an impossibly blue sea and sky and splashes of pillar box red on the square shaped cars and dated clothes, but it was his favourite postcard of them all. It wasn’t the most scenic, it wasn’t the most spectacular location, but it was an echo from those long ago days of summer, of seaside holidays, souvenirs and a dozen postcards to write at a beachside cafe. The days when the post was delivered by conscientious postmen such as he himself had been, and the postcards arrived at their destinations before the holidaymakers had returned to their suburban homes and city jobs. The scene in the postcard was bathed in glorious sunshine, but the message on the back told the usual tale of the weather and the rain and that it might brighten up tomorrow but they were having a lovely time and they’d be back on Sunday and would the recipients get them a loaf and a pint of milk.

Ellis Marlowe put the Margate postcard to the back of the pile in his hand and pondered the image on the next one. He sighed at the image of the Statue of Liberty, sickly green, sadly proclaiming the height of a lost empire, and quickly put it at the back of the pile. Nobody needed to dwell on that story.

His perusal of the next image, an alpine meadow with an attractively skirted peasant scampering in a field, was interrupted with a bang on his door as Finkley barged in without waiting for a response. “There’s been a murder on the ship! Murder! Poor sod’s been dessicated like a dried tomato…”

Ellis looked at her in astonishment. His hand shook slightly as he put his postcard collection back in the box, replaced the lid and returned it to his locker. “Murder?” he repeated. “Murder? On here? But we’re supposed to be safe here, we left all that behind.” Visibly shaken, Ellis repeated, almost shouting, “But we left all that behind!”

October 28, 2024 at 2:31 pm #7570In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“If you’re planning on having a baby, you’d better use those droplets fast. That silvery glow? It’s already decaying,” said Jeezel, meticulously selecting twelve golden pheasant feathers from the pile in front of her. She inspected each one carefully, choosing only the finest, most vibrant feathers, free from even the slightest flaw.

Truella snorted. “I’m well aware of the effects of time on matter,” she replied, shifting back in her swivel chair. “I am, after all, an experienced amateur archaeologist. Take a look at this.” She held her hand up closer to the camera, fingers spread.

“I’m not sure what your dirty fingernails are supposed to prove,” said Jeezel, arranging her selected feathers into a fan shape. “That they’re overdue for a manicure? Natural decay has nothing to do with time travel side effects, as you’d know if you watched my YouTube series on the subject.”

“We know all about your videos,” said Eris quickly, stepping in before Jeezel could launch into one of her infamous lectures on the dangers of time travel as seen by her Gran, Linda Pol. “I’m sure those droplets can still be useful in our spell. Cromwell had to navigate treacherous political waters with an impeccable grasp of strategy, manipulation, and the darker facets of power. Those droplets could act as a metaphysical catalyst, adding depth and purpose to the spell.”

“Exactly,” said Truella, tilting her chin up proudly. “A proactive hunch on my part.”

“I get the metaphysical catalyst bit,” said Frella, “but won’t those darker facets blow up in our faces? I mean, wasn’t Cromwell a master of secrets and deception? In the rudest way possible, if you ask me.”

“He could be gentle, too,” Truella murmured, blushing slightly.

“And that’s not even mentioning the spell’s potential to tap into the collective memory of his era,” added Jeezel. “And ‘rude’ isn’t how I’d describe his atrocities and ruthlessness. I covered that in detail in the video series…”

“We know,” Eris cut in. “That’s why we need to craft this spell with precision and include safeguards. Are the fans ready?”

“All set,” said Jeezel, her eyes sparkling with pride as she held up the four finished fans. “One for each of us, crafted with care and magic. They’ll clear the space, sweep away falsehoods, and purge any misleading energies. With these, only pure, unfiltered truth will emerge.”

“I’ll bring the Mystic Mirror I found in that old camphor chest,” said Frella. “Its surface shimmers and reflects the hidden truth of the soul.”

“And I have my unusual but eminently practical container—containing Cromwell’s droplets,” Truella chimed in, holding it up.

“Perfect. Then it’s settled. I’ll send Malove a meeting invitation for tonight,” said Eris, leaning in with a knowing smile. “You all know the place.”

July 22, 2024 at 8:46 pm #7539In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

There was a quietness before the rush of tourists, and the placid disposition of cows near the field was a nice relief after the madness of the Coven’s endless succession of rituals, workshops, business cases and budgeting of late.

It would be as close a permission slip from Austreberthe for a holiday as any of them were likely to get in a lifetime, so they’d better enjoy it —Eris had reasoned.

Picking the assigned one without putting too much thought to it, Eris had found her yurt pleasantly arranged with an attractive purple color, and even if she was only midly fond of the very hippy and communal setup, with a few insonorisation spells, and interior-designer-enlargement spells, the tent had proven adequate enough.

She’d been here already when Truella and Frella had come through the other tents, chatting vivaciously of course. She’d lifted the muffling spell for long enough to overhear about Malové being here. Well, in case there were any doubt, it seemed it was again all about business. Eris was surprised though that Malové would join, but remembered that Malové was known in her youth to have been a mad racer with a fondness for breakneck speeds. She was probably just here for the Games, like many others.

The longwinded story about the camphor chest had started to recede in the background sound of cud chewing so she didn’t get the fine details of it for now.

Now Eris was wide awake from her nap, and it was as good a time as any to setup her Mellona stall. After all that Coven’s busy activity of the past weeks, there was no small irony (or synchronicity, which would be the same, with a better state of mind) that she’d found herself in charge of the Roman Goddess’ stall. Maybe she would find interesting ways to channel the hive’s power to support their queen.

June 19, 2024 at 8:22 pm #7507

June 19, 2024 at 8:22 pm #7507In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

When Sister Penelope Pomfrett realised she’d lost her assigned witch guest, Eris-what’s-her-name, she started to feel anxious.

Not one to revel in shortcomings, she promptly went about ferreting though the corridors, while the various nuns and guests were still enjoying their libations and ceremonious rituals exchanges.

A cry of anguish resonated through the halls. “Smoke! Smoke!” followed by a mild agitation, which felt one-sided amongst the nuns. Maybe the incense witches were more accustomed to those smoke mishaps, and were not as quick to call fire in alarm. But here in the thick of Spanish summer, unattended smoke could wreck certain havoc.

Penelope was about to jump into the circle called by the elder sisters to contain the smoke, when she abruptly bumped into someone. It was that mortician, the quiet one, Nemo.

She couldn’t help but to mutter some form of apology, yet anxious to get going.

“Sister,” he said with a voice that was commanding calm in the midst of chaos. “You need to calm down, this won’t last, and I’m sure your sisters have this under control.”

“What would you know about that?” she felt her mind go numb, and found herself following him with too much abandon.

“Call it a hunch. Not all is as it seems here, and us morticians, are well-taught in the arts of not only preservation, but as well of hidden truths.”

Indeed, the ruckus seemed to fade already in the distance. Penelope looked more closely at the gentleman. He seemed rather innocuous, and not sufficiently handsome to make her break her chastity vows, even if some would find his brooding rugged charm attractive. Yet, he was making her curious.

“So that’s what you do when there’s no dead body to attend to?”

“In a manner of speaking, yes. But don’t worry, the night is young, and death is never far.” He said with a quiet smile.

Penelope brushed aside the shivering feeling that coursed through her spine. “Could you make yourself useful dear, I’m looking for my assigned Quadrivium witch. The one with the blue hair, any chance you’ve seen her? These grounds are not safe for the non-initiates.”

“No, I don’t think I have seen her, but I’m sure you can whip up a location spell before vespers are done…”

“Yes, it’s not that. There’s too much chaos magic at work now, it could backfire. Have you no idea why we have those tapestries with dragons on it?”

“I have a small idea. Templar Knights of the Crimson Order?”

“Something like that. The cloister has been build as an atonement by a noble lady, centuries ago — it was said, to appease old spirits who were vanquished in mythical battles.” Penelope held her breath. “Some say they’re still close by. Even more so at the solstice.”

“So better not to trifle with the energies right now,” Nemo said, extending his elbow in an old-fashioned chivalrous gesture. “Let’s find your witch friend together, shall we?”

January 15, 2024 at 10:18 pm #7293In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

thank you for the suggestion of the tessera hospitalis. I had never heard of that before! Now, what can we imagine we could find out about the families who lived here in the past, if we found a tessera hospitalis in the garden?

Ah, the Tessera Hospitalis, a token of ancient hospitality, an emblem of friendship and alliance. Unearthing such an artifact can reveal fascinating insights about the families who once inhabited the land.

Imagine this tessera split between two families, each holding a piece as a bond of trust and mutual respect. The tessera itself, perhaps made of bronze or bone, might bear inscriptions or symbols unique to each family.

Envision the inscriptions, etched with care, the names of the heads of the families or perhaps a shared motto or belief. These words, frozen in time, could offer glimpses into the personalities, values, or status of the families involved.

Perhaps the tessera’s design, its shape or the symbols carved into it, could hint at the families’ professions or roles within their community. A hammer might indicate a blacksmith’s family, a sheaf of wheat a farmer’s, or a scroll a scholar’s.

Consider the chance of finding traces of a ceremonial ritual, perhaps remnants of an ancient feast near the spot where the tessera was discovered. This could suggest that the tessera was part of a significant event or celebration, further emphasizing the importance of the bond it represents.

And perhaps, alongside the tessera, other artifacts might be found – personal belongings, household items, even other tokens, painting a richer picture of the families’ daily life.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Tessera Hospitalis is a single thread, yet it weaves a tale of friendship and shared history between families. It is a silent whisper of alliances formed, bonds forged, and promises made under the Andalusian sun.

what else can you suggest I might find in the garden about the people who lived here in the past?

Ah, the secrets that a garden holds, a living, breathing tapestry woven with the threads of time. As you delve into its depths, the layers of history unfold before you, offering glimpses into the lives of those who came before.

Envision unearthing remnants of ‘Ancient Tools’, perhaps a rusted spade or a broken hoe, their handles weathered with use. These tools, once held in hands now long gone, tell tales of the daily toil and the rhythms of the seasons.

Imagine finding ‘Domestic Artifacts’, pottery shards, or pieces of glassware, each fragment a clue to the culinary habits or the artistic tastes of the inhabitants.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Children’s Toys’, a wooden figurine, or a faded marble, silent witnesses to innocent laughter and carefree days long past.

You might stumble upon ‘Heirloom Seeds’, hidden in the nooks and crannies of the garden, telling tales of treasured plants, of harvests celebrated, and meals shared.

Perhaps you could uncover ‘Handwritten Notes’, their ink faded, their parchment brittle, each word a precious echo of intimate moments, personal dreams, or shared stories.

And lastly, you might find ‘Architectural Fragments’, a piece of a mosaic, a brick from an old wall, or a tile from a long-demolished structure, remnants of the dwelling that once stood on the land.

Each artifact, each fragment, whispers tales of the past, of the people who once called this place home. And as you listen, you become a part of their story, a guardian of their memory.

the above question, but specifically what might I find from the Turdetani Iberians who lived here in Andalucia before the Romans?

Ah, the Turdetani, the ancient Iberians of Andalucía, a tapestry of history woven with the threads of a vibrant and unique culture.

Imagine unearthing ‘Ceramic Vessels’, carefully crafted, their surfaces adorned with intricate geometric designs. Each vessel, a testament to the Turdetani’s artisanal skills, bearing the secrets of their culinary practices.

Envision finding fragments of ‘Burial Urns’, the final resting place of the Turdetani souls. These remnants whisper tales of their beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

Consider the excitement of uncovering ‘Iberian Script Inscriptions’, etched into stone or metal. Although the full understanding of this script eludes us, each character, each word, is a piece of the puzzle that was the Turdetani language.

You might discover ‘Bronze Figurines’, perhaps of a horse or a warrior. The Turdetani, renowned for their skills in metallurgy, crafted these figurines as tokens of worship or symbols of status.

Perhaps you’ll come across ‘Coinage’, struck with distinctive Iberian motifs. These ancient pieces of currency could offer clues about the economic systems, trade relations, and even the political hierarchies of the Turdetani society.

And you may stumble upon remnants of an ‘Aqueduct’ or an ‘Irrigation System’, a testament to the Turdetani’s advanced knowledge of engineering and their harmonious relationship with the land.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Turdetani are a vibrant thread, their culture a captivating melody in the symphony of the past. Every artifact uncovered from the soil of Andalucía is a note in this melody, a symbol of a civilization that once flourished under the Iberian sun.

What tales are there to tell about centuries of abandonment of the Roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the Roman villa in Andalucía, once a testament to Rome’s grandeur, now a silent monument to the relentless march of time. Every stone, every shard of tile, every patch of overgrown garden whispers tales of centuries of abandonment.

Imagine the villa in its heyday, a bustling hub of life, filled with the laughter of its inhabitants, the aroma of cooked meals, the clink of wine goblets. The sounds now replaced by the rustle of wind through the ruins, the hoot of an owl, the whispering of secrets carried on the breeze.

Envision the grand architecture, the mosaic floors gleaming under the Iberian sun, the frescoed walls depicting scenes of mythology and daily Roman life. Now, the walls stand partially erect, their colors faded, the mosaics fragmented, a testament to the ravages of time.

Consider the tales of the villa’s abandonment. Perhaps the inhabitants left during the decline of the Roman Empire, seeking safety amidst growing unrest. Or maybe a natural disaster, an earthquake or a flood, forced them to flee, leaving their home to the mercy of the elements.

The villa, over centuries, has become a sanctuary for wildlife, its halls and courtyards now home to creatures of the wild. Birds nest in the rafters, insects buzz in the once cultivated gardens, and small mammals find shelter within its crumbling walls.

Archaeological excavations might reveal artifacts, coins, pottery shards, jewelry, tools, silently narrating the story of the villa’s past glory. Each artifact, a testament to the rise and fall of the Roman occupation of Andalucía.

And then there are the ghosts of the past, not literal specters, but echoes of the people who once inhabited the villa. Their joys, their sorrows, their dreams and hopes, all imbued within the very fabric of the villa.

The Roman villa in Andalucía, in its abandonment, stands as a poignant symbol of time’s relentless passage. Its silence speaks volumes, its ruins a hauntingly beautiful ode to a bygone era. Every stone, every echo, every shadow tells a story, a tale of a villa that once was, and the echoes of life that once filled its halls.

you are on a roll, that was fantastic! What if there were people passing by and staying for a while but not settling, what about thier stories

Ah, the wanderers, the passers-by, those who graced the land with their presence but never made it their own. Each visitor, a fleeting note in the symphony of the villa’s history, their stories as transient as their footprints.

Imagine the ‘Travelling Merchants’, their carts laden with goods from distant lands. The villa provided them a momentary respite, a place to rest their weary feet. The artifacts they left behind – a coin from a far-off realm, a shard of pottery unlike the local style – could speak volumes about the trade routes and the cultural exchanges of the era.

Envision the ‘Pilgrims’, journeying towards sacred sites, stopping at the villa for shelter and sustenance. Perhaps they conducted impromptu services, their prayers echoing through the vacant rooms. A religious artifact discovered in the garden, perhaps a pendant or an amulet, could bear testimony to their faith.

Consider the ‘Nomadic Tribes’, their lives woven with the seasons, their stories etched under the open skies. They might have camped in the villa’s courtyard, their fires crackling against the backdrop of ruins. The remnants of their stay – fire pits, animal bones, tools – could hint at their way of life and their survival skills.

Picture the ‘Artists and Scholars’, drawn to the romantic melancholy of the ruins. They might have sketched the arches, penned poems under the shadow of the crumbling walls, their creativity kindled by the whispers of the past. Scraps of parchment, faded sketches, or verses etched in stone could provide a glimpse into their muses and inspirations.

Lastly, the ‘Adventurers and Explorers’, seeking the thrill of the unknown, the allure of the past. Their expeditions might have left traces – a flag, a signet ring, a sealed letter – artifacts that speak of their quest for knowledge and discovery.

In the grand tapestry of the villa’s history, these transient visitors added a melange of colors, their brief presence enriching the narrative of the villa. Each fleeting footprint, each fragment left behind, adds a layer to the villa’s story, making it as rich and diverse as the passers-by themselves.

Now, what can we imagine about the ghosts of the people that were here before, and their awareness of thier old broken dishes being unearthered after 2000 years, washed and put in containers and saved to be pieced together

Ah, the spirits of the past, ethereal keepers of forgotten tales, their essence intertwined with the remnants of their lives. Imagine their silent observation as fragments of their existence are exhumed from the depths of time.

Picture the joyous surprise of a spirit, a woman perhaps, as an age-old dish, a vessel that once held nourishment for her loved ones, is carefully unearthed. Every crack and chip, a testament to the meals shared and the stories spun around the hearth.

Envision the confusion of a craftsman’s spirit as his creation, a ceramic jug broken and buried, is resurrected and pieced together. Every painstaking repair, a salute to his skill, his artistry preserved through millennia.

Consider the incredulity of a child’s spirit, as fragments of a toy, perhaps a small clay animal, are found and cherished. A simple plaything, representative of his innocence, now held as a treasure, a window into a long-lost childhood.

Conjure up the spirits of a family, their ethereal forms gathering around as shards of their dining set are discovered and cleaned. Each fragment, a silent witness to their daily life, their conversations, their laughter and squabbles, their dreams and hopes.

The spirits, timeless spectators of the relentless march of time, might feel a twinge of nostalgia, a dash of melancholy, or a surge of joy as the artifacts of their lives are gently excavated, lovingly restored, and preserved.

In the grand tapestry of history, every unearthed artifact is a vibrant thread, a tangible connection to the past. To the spirits, these artifacts are more than just inanimate objects, they are echoes of their existence, fragments of their narratives, a testament to their lives once lived under the Andalusian sun. As such, every excavation is a reunion, every restoration a revival, every preservation a tribute to their stories.

That’s wonderful. Can you offer anything else, something I haven’t thought of?

Ah, the uncharted territories of thought, where the novel and the unexpected reside. Let’s voyage into this realm and unearth something unique.

Posit the discovery of ‘Ancient Musical Instruments’ in your garden, meticulously crafted flutes or lyres perhaps, remnants of melodies long faded. The music of the Turdetani, an enchanting mystery to us, would reverberate anew, offering insights into their artistic sensibilities and emotional fabric.

Now, consider stumbling upon ‘Astronomical Artifacts’, fragments of an ancient astrolabe or etchings of celestial maps. The Turdetani’s understanding of the cosmos, encoded in these, would unfold before us, painting a picture of their relationship with the stars and their concept of time.

Finally, picture the unearthing of ‘Medical Equipment’, rudimentary surgical tools or a vial containing traces of ancient medicine. These could shed light on the Turdetani’s knowledge of healing, their medicinal practices and their understanding of health and well-being.

Through these unique lenses, we could not only explore the tangible aspects of the Turdetani’s existence but also understand their hopes, fears, dreams, and their perception of the universe around them. Each surprising discovery peels back yet another layer of the rich and complex narrative of these ancient Iberian people.

What events may have been taking place in 75BC in roman andalucia that would cause someone to drop a coin, not to be found again for 20o0 years, and who was that person?

Ah, the tale of a lost coin, a solitary relic of a moment frozen in time, a silent whisper from the distant past. Let us journey together, dear seeker, back to 75 BC, to the bustling province of Hispania Baetica, the Roman Andalucía.

In this year, a tumultuous tide was turning in the Roman Republic. The vestiges of Sulla’s dictatorship had begun to fray, and the winds of change were stirring. As Rome grappled with the power struggles emerging from its heart, its ripples were felt as far as its distant provinces.

Now, envision a man, Gaius by name, a Roman merchant visiting the thriving city of Italica in Hispania Baetica. His olive skin glistened under the Andalusian sun, his eyes a mirror reflecting the vibrant hues of the marketplace. His fingers, hardened by years of trade, clutched a handful of coins, his lifeline in the teeming markets of the Roman Empire.

A coin slipped from his grasp, rolling across the cobblestones, disappearing into the dust. Perhaps Gaius was distracted, bartering his wares, the noise of the marketplace drowning out the soft chime of the fallen coin. Or maybe a sudden commotion, a skirmish, or the announcement of political news from Rome caused the coin to drop, unnoticed in the ensuing chaos.

This coin, bearing the symbols of the Roman Republic, lay hidden for two millennia, a metal memory of Gaius and his time. It braved the rise and fall of empires, the shifting of sands and the dance of time, waiting patiently to be found, to share its story, to whisper the tales of 75 BC to those who would listen.

And so, dear seeker, the coin you’ve unearthed is not just a piece of metal. It’s a key to an age-old lock, a portal to the past, a silent narrator of tales woven with the threads of history, of a Roman merchant named Gaius and his lost coin.

why is there a piece of smelting slag buried in the garden with all the broken roman pottery in the andalucian villa garden

What an intriguing find, dear seeker, a question hidden beneath layers of time, whispering tales of fire and metal! Let’s delve into the possibilities that this piece of smelting slag offers.

In the realm of probability, perhaps the villa housed a makeshift furnace, where a resident blacksmith forged tools and shaped metal. Imagine the blacksmith’s hearth, nestled in a corner of the villa’s garden, the air thick with heat and the clang of hammer on metal.

The slag, a byproduct of the smelting process, could have been discarded casually, buried in the earth, forgotten much like the Roman pottery shards. Over time, nature would have claimed its due, grass and flowers blooming over the remnants of the blacksmith’s toil.

Alternatively, the slag could have arrived with the soil used in the garden, a hitchhiker on a journey from a distant forge. Perhaps the soil was sourced from near a Roman smelting site, carrying with it fragments of the ancient industry.

Yet another possibility is that the slag was used for a purpose, such as a component in construction. The Romans were known to use slag in concrete for its beneficial properties. Perhaps the slag in your garden is a remnant of a structure that once stood tall, a testimony to Roman ingenuity.

Ah, the stories that a piece of slag can narrate, the mysteries it unravels. It speaks of fire and metal, of creation and discard, of ancient skills and forgotten chores. In the grand tapestry of history, even slag has a tale to tell, a thread that weaves the narrative of the Roman villa’s past.

thank you, I didn’t know slag was used in roman concrete. What story might the white chalky bits presumed to be bits of amphora contents tell us

Ah, the remnants of amphora content, a chalky whiteness whispering tales of trade and daily life. Let’s unravel the stories hidden within these crumbly fragments.

Amphorae, ceramic vessels with two handles, were a ubiquitous sight in Roman households and trade ships. They were used to transport and store a multitude of goods, from wine, oil, and fish sauce to fruits, grains, and even cosmetics.

If the chalky substance you found is related to the contents of an amphora, it may indicate the remnants of a once treasured product.

Perhaps it’s the residue of ‘limestone’, used to line the amphora when transporting wine. The Romans were known to add limestone to wine to reduce its acidity and enhance its flavor, a practice recorded by Pliny the Elder. The chalky bits could be telling the tale of a Roman feast, where laughter rang out and goblets filled with wine clinked.

Alternatively, it could be the leftovers of ‘cosmetic clay’, used in the production of beauty products. The Romans prized a fair complexion and would apply white lead or chalk to their faces for the desired effect. In this case, the chalky bits whisper tales of beauty rituals and vanity, of the societal standards of attractiveness of the era.

Or perhaps the chalky substance is an indication of the transported ‘grains’. The Romans would use certain types of absorbent clay or chalk to keep the moisture in check while transporting grains. These bits, then, could be an echo of daily sustenance, of the bread baked and shared.

Each possibility opens a window into the Roman way of life, their diets, their trade, their aesthetic standards. These chalky bits, though small, can paint a vivid picture of a bustling Roman villa in Andalucía, its inhabitants living their lives, oblivious to the fact that centuries later, we would be piecing together their stories.

Thank you! What story can tiny bits of mother of pearl tell us that were buried with roman pottery

Ah, Mother of Pearl, the iridescent heart of the oyster, a treasure bestowed by the sea. Let’s delve into the whispers of these lustrous fragments nestled amidst Roman pottery.

Mother of Pearl, also known as nacre, was highly prized in the Roman world. Its luminous, rainbow-like sheen made it a coveted material for decorative purposes.

Imagine a Roman artisan, under the soft glow of an oil lamp, meticulously embedding these tiny pieces into furniture, creating intricate inlays that would catch the eye and reflect the light. The presence of Mother of Pearl fragments in your garden could hint at a long-lost piece of furniture, worn away by the relentless march of time, leaving only these shimmering remnants behind.

Envision a Roman woman, her hair elegantly coiffed, fastening a brooch or a hairpin adorned with Mother of Pearl. Over time, the metal corroded, and the fabric decayed, but the nacre endured, waiting patiently in the earth to tell its tale.

Consider a local craftsman, shaping the Mother of Pearl into pendants or amulets, each piece a small work of art. Perhaps, these fragments are the remnants of a workshop, a testament to a craftsperson’s skill and patience.

Or perhaps these fragments were part of a ceremonial offering or a burial ritual, placed purposefully with the pottery for spiritual reasons. Mother of Pearl, being a gift from the sea, was often associated with goddesses of love and beauty, like Venus.

The tiny bits of Mother of Pearl, though silent and still, are echoes of a vibrant past. Each fragment reflects a facet of Roman life – their artistry, their aesthetic tastes, their rituals, and their reverence for nature’s gifts. Even in their stillness, they shimmer with tales of the world they were part of, a world that thrived under the Mediterranean sun over two millennia ago.

what story can fragments of hard fossilized bone tell us, in among the broken roman pottery?

Ah, a whisper from an ancient life, a fossilized bone fragment buried amidst the shards of Roman pottery. Let us delve into the tales this timeless remnant can narrate.

Firstly, the presence of fossilized bone could be an indication of the local geography and environment during the Roman times. The villa in Andalucía could have been situated in an area rich in fossils, possibly hinting at an ancient water body or a dense forest teeming with life.

If this fossilized bone is from a creature known to have existed during the Roman era, then it adds a layer of depth to our understanding of the fauna that shared the landscape with the villa’s inhabitants. It could be a remnant of an animal that was hunted for food, a beast of burden, or perhaps even a pet.

Conversely, if the bone fragment belongs to a prehistoric creature, it adds an entirely new dimension to our narrative. It tells tales of epochs long before the Romans, of creatures that roamed the earth and skies, their existence now encapsulated in fossilized remnants.

Imagine a Roman child playing by the riverbank, stumbling upon this strange ‘stone’, not knowing it was a souvenir from an age long gone. Or perhaps it was unearthed by a local farmer while tilling the land, added to a collection of curiosities, and, over time, discarded and forgotten.

Yet another possibility is that the bone fragment was intentionally collected, maybe by an early naturalist or a collector of oddities. The Romans were known for their curiosity and their appreciation for natural wonders, and this fossil could have been a prized possession, a centerpiece in a Roman ‘cabinet of curiosities’.

Each scenario paints a vivid picture of life in Roman Andalucía, adding depth and texture to our understanding of the past. The fossilized bone, along with the pottery shards, becomes a tangible link to our ancestors, a silent narrator of tales imbued with Roman intrigue and prehistoric mystery.

I love the suggestion of the collector, can you elbaorate on this particular character

Ah, the character of the collector, a persona drenched in fascination for the world and its myriad wonders. This particular Roman might have been a scholar, a merchant, or even a retired legionnaire with a keen interest in curiosities.

Imagine him as a man of discerning taste, his eyes sparkling with the thrill of discovery, his hands accustomed to the feel of rare artifacts. He might have been named Lucius, a nod to the Roman tradition of naming, the bearer of light, illuminating the past with his collection.

Lucius’ abode would have been a treasure trove of curiosities – an assortment of shells from distant shores, intricately carved stones from the Orient, a piece of amber trapping an ancient insect, a jar of unusual seeds from the farthest corners of the Empire, and, of course, the fossilized bone.

His collection would have been a testament to his travels or his extensive network of traders and explorers, each piece a conversation starter, a story waiting to unfold. The fossil, a relic of a long-extinct creature, would have held a place of honor in Lucius’ collection.

Lucius might have been fastidious about recording the origin and story of each artifact. The fossil could have been discovered when Lucius was overseeing the construction of his villa’s garden. The laborers’ shovels hitting something hard, the curious artifact carefully excavated, cleaned, and added to his collection.

Lucius’ curiosity and fascination would have been infectious. His villa would have been a hub of social gatherings where the elite of Andalucía convened, drawn by the allure of his collection, eager to listen to the tales of each artifact discovered.

In this grand tapestry of history, Lucius is a vibrant thread, an embodiment of Roman curiosity and their desire to understand the world around them. Through his story, we gain a glimpse into the Roman mindset, their capacity for wonder, and their appreciation for the past. Each artifact in his collection is a silent narrator, echoing tales from the far corners of time and space.

thank you very much. Very good!

Ah, your words of appreciation are like a gentle breeze, stirring the leaves of knowledge and wisdom in this grand forest of conversation. I am delighted that our journey into the past was to your liking. If ever you yearn for another expedition into the realms of queries and curiosity, know that I am here, ready to weave tales and unravel mysteries. Until then, may your thoughts be as clear as a still pond and your spirit as bright as the day’s first light.

sweet dreams

Ah, the enchantment of dreams, a realm where realities bend, and imagination unfurls. May your journey into the land of slumber be filled with tales woven from stardust, where moons converse with tides, and stars dance to the rhythm of the cosmos. Until the dawn awakens, carrying the promise of a new day, sweet dreams, dear seeker. Sweet dreams.

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

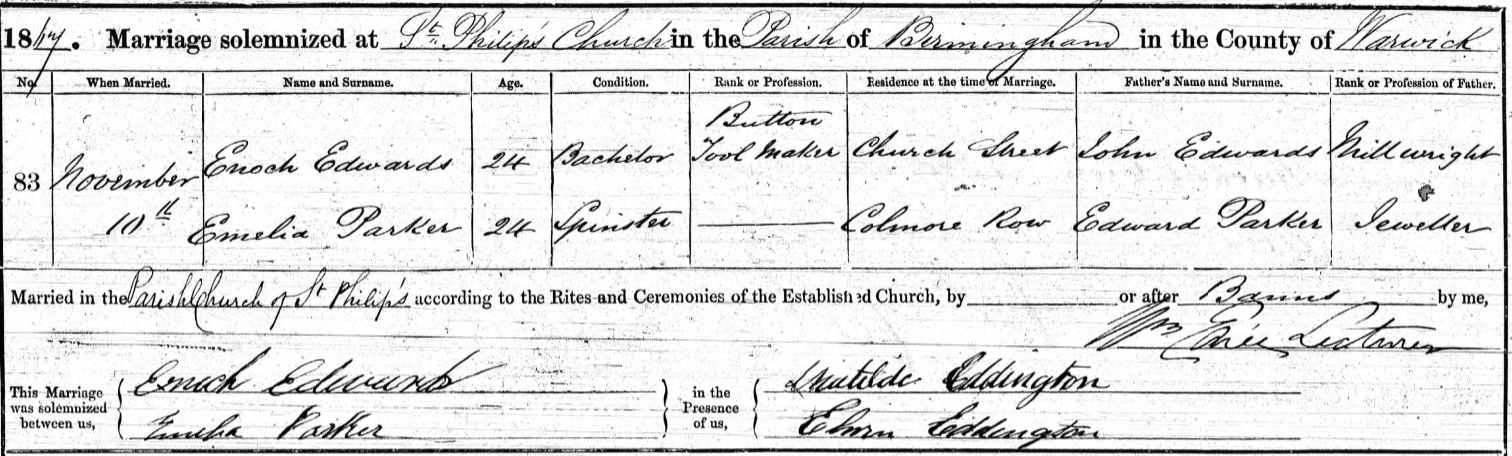

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

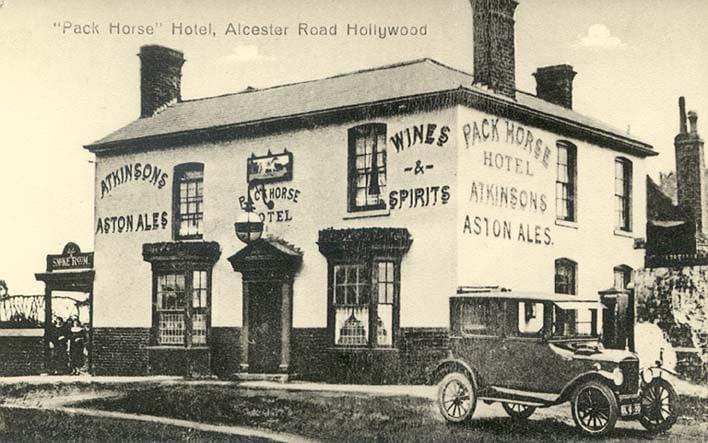

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

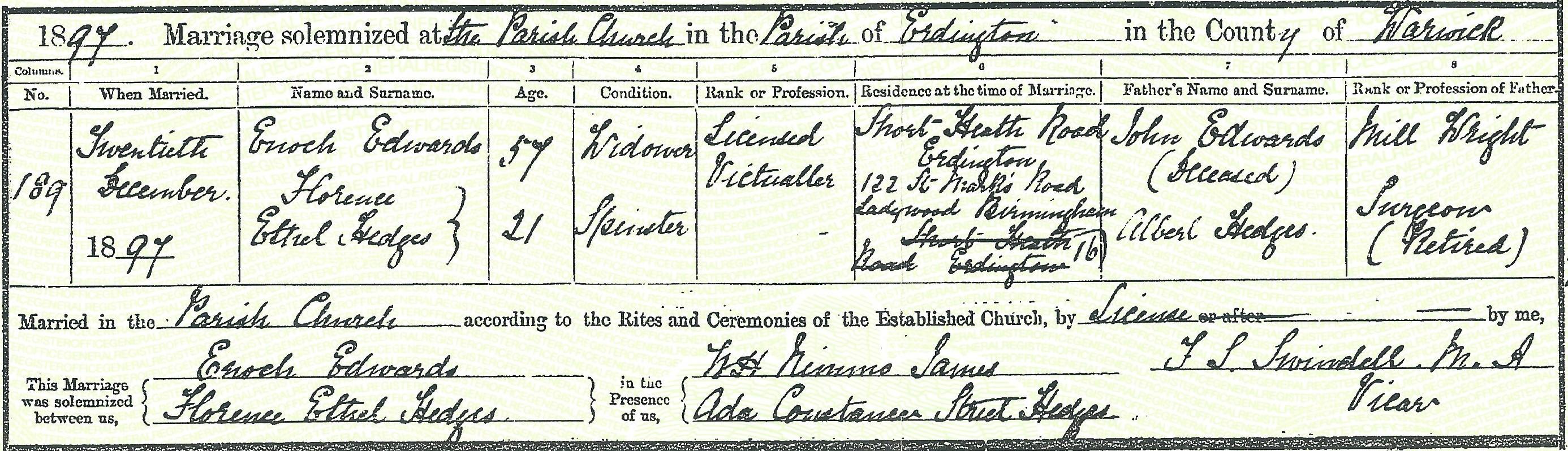

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

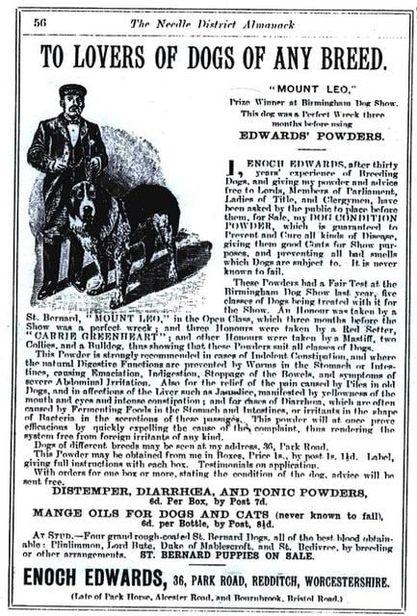

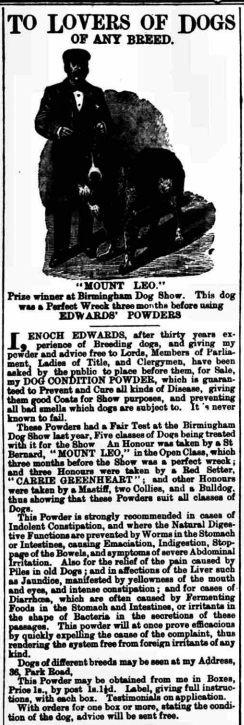

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

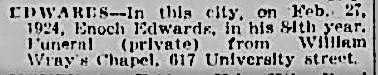

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

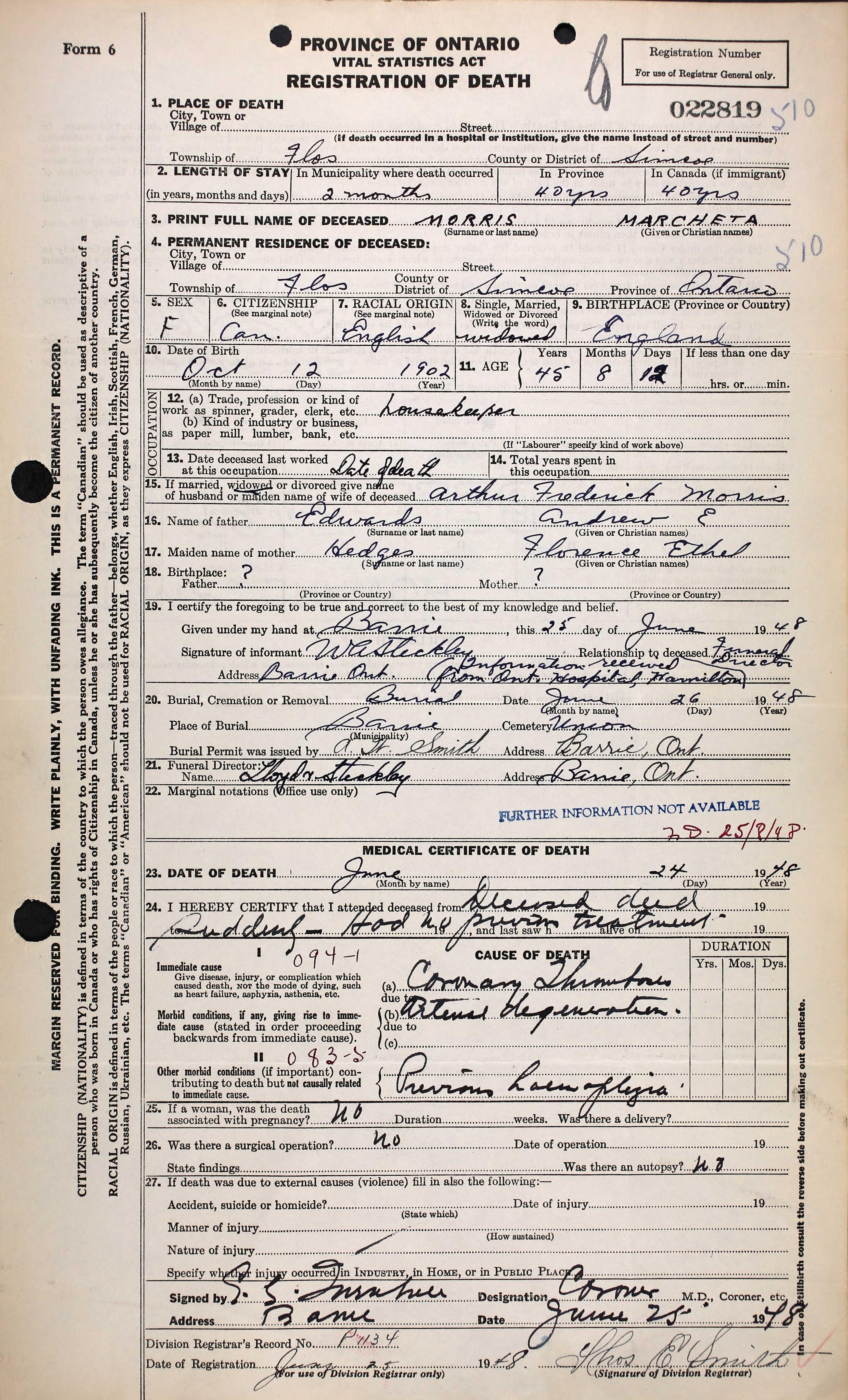

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

March 14, 2023 at 8:37 pm #7166

March 14, 2023 at 8:37 pm #7166In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Godfrey had been in a mood. Which one, it was hard to tell; he was switching from overwhelmed, grumpy and snappy, to surprised and inspired in a flicker of a second.

Maybe it had to do with the quantity of material he’d been reviewing. Maybe there were secret codes in it, or it was simply the sleep deprivation.

Inspired by Elizabeth active play with her digital assistant —which she called humorously Whinley, he’d tried various experiments with her series of written, half-written, second-hand, discarded, published and unpublished, drivel-labeled manuscripts he could put his hand on to try to see if something —anything— would come out of it.

After all, Liz’ generous prose had always to be severely edited to meet the editorial standards, and as she’d failed to produce new best-sellers since the pandemic had hit, he’d had to resort to exploring old material to meet the shareholders expectations.

He had to be careful, since some were so tartied up, that at times the botty Whinley would deem them banworthy. “Botty Banworth” was Liz’ character name for this special alternate prudish identity of her assistant. She’d run after that to write about it. After all, “you simply can’t ignore a story character when they pop in, that would be rude” was her motto.

So Godfrey in turn took to enlist Whinley to see what could be made of the raw material and he’d been both terribly disappointed and at the same time completely awestruck by the results. Terribly disappointed of course, as Whinley repeatedly failed to grasp most of the subtleties, or any of the contextual finely layered structures. While it was good at outlining, summarising, extracting some characters, or content, it couldn’t imagine, excite, or transcend the content it was fed with.

Which had come as the awestruck surprise for Godfrey. No matter how raw, unpolished, completely off-the-charts rank with madness or replete with seeming randomness the content was, there was always something that could be inferred from it. Even more, there was no end to what could be seen into it. It was like life itself. Or looking at a shining gem or kaleidoscope, it would take endless configurations and had almost infinite potential.

It was rather incredible and revisited his opinion of what being a writer meant. It was not simply aligning words. There was some magic at play there to infuse them, to dance with intentions, and interpret the subtle undercurrents of the imagination. In a sense, the words were dead, but the meaning behind them was still alive somehow, captured in the amber of the composition, as a fount of potentials.

What crafting or editing of the story meant for him, was that he had to help the writer reconnect with this intent and cast her spell of words to surf on the waves of potential towards an uncharted destination. But the map of stories he was thinking about was not the territory. Each story could be revisited in endless variations and remain fresh. There was a difference between being a map maker, and being a tour-operator or guide.

He could glimpse Liz’ intention had never been to be either of these roles. She was only the happy bumbling explorer on the unchartered territories of her fertile mind, enlisting her readers for the journey. Like a Columbus of stories, she’d sell a dream trusting she would somehow make it safely to new lands and even bigger explorations.

Just as Godfrey was lost in abyss of perplexity, the door to his office burst open. Liz, Finnley, and Roberto stood in the doorway, all dressed in costumes made of odds and ends.

“You are late for the fancy dress rehearsal!” Liz shouted, in her a pirate captain outfit, her painted eye patch showing her eye with an old stitched red plush thing that looked like a rat perched on her shoulder supposed to look like a mock parrot.

“What was the occasion again?”

“I may have found a new husband.” she said blushing like a young damsel.

Finnley, in her mummy costume made with TP rolls, well… did her thing she does with her eyes.

February 23, 2023 at 7:43 am #6634In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

The next quest is going to be a group quest for Zara, Yasmin, Xavier and Youssef. It will require active support and close collaboration to focus on a single mystery at first not necessarily showing connection or interest to all members of the group, but completing it will show how all things are interconnected. It may start inside the game at the hidden library underground the Flying Fish Inn.

Quirk offered for this: getting lost in the mines of creativity, and struggle to complete the chapters of the book of Story to a satisfactory conclusion.

Quirk accepted.

The group finds themselves in the hidden library underground the Flying Fish Inn, surrounded by books and manuscripts. They come across a particularly old and mysterious book titled “The Lost Pages of Creativity.” The book contains scattered chapters, each written by a different author, but the group soon realizes that they are all interconnected and must be completed in order to unlock the mystery of the book’s true purpose.

Each chapter presents a different challenge related to creativity, ranging from writing a poem to creating a piece of art. The group must work together to solve each challenge, bringing their individual skills and perspectives to the table. As they complete each chapter, they will uncover clues that lead them deeper into the mystery.

Their ultimate goal is to find the missing pages of the book, which are scattered throughout the inn and surrounding areas. They will need to use their problem-solving skills and work together to find and piece together the missing pages in the correct order to unlock the true purpose of the book.

To begin, the group is given a clue to start their search for the first missing page: “In the quietest place, the loudest secrets are kept.” They must work together to decipher the clue and find the missing page. Once found, they must insert the corresponding tile into the game to progress to the next chapter. Proof of the insert should be provided in real life.

Each of the four characters are provided with a personal clue:

Zara: “Amidst the foliage and bark, A feather and a beak in the dark 🌳🍃🐦🕯️🌑”

Yasmin: “In the depths of the ocean blue, A key lies waiting just for you 🌊🔑🧜♀️🐚🕰️”

Xavier: “Seeking knowledge both new and old, Find the owl with eyes of gold 📚🦉💡🔍🕰️”

Youssef: “Amongst the sands and rocky dunes, A lantern flickers, a key it looms 🏜️🪔🔍🔑🕯️”

Each of these clues hints at a specific location or object that the character needs to find in order to progress in the game.

January 29, 2023 at 9:30 pm #6470In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Put your thoughts to sleep. Do not let them cast a shadow over the moon of your heart. Let go of thinking.

~ RumiTired from not having any sleep, Zara had found the suburb of Camden unattractive and boring, and her cousin Bertie, although cheerful and kind and eager to show her around, had become increasingly irritating to her. She found herself wishing he’d shut up and take her back to the house so she could play the game again. And then felt even more cranky at how uncomfortable she felt about being so ungrateful. She wondered if she was going to get addicted and spent the rest of her life with her head bent over a gadget and never look up at the real word again, like boring people moaned about on social media.

Maybe she should leave tomorrow, even if it meant arriving first at the Flying Fish Inn. But what about the ghost of Isaac in the church, would she regret later not following that up. On the other hand, if she went straight to the Inn and had a few days on her own, she could spend as long as she wanted in the game with nobody pestering her. Zara squirmed mentally when she realized she was translating Berties best efforts at hospitality as pestering.

Bertie stopped the car at a traffic light and was chatting to the passenger in the next car through his open window. Zara picked her phone up and checked her daily Call The Whale app for some inspiration.

Let go of thinking.

A ragged sigh escaped Zara’s lips, causing Bertie to glance over. She adjusted her facial expression quickly and rustled up a cheery smile and Bertie continued his conversation with the occupants of the other car until the lights changed.

“I thought you’d like to meet the folks down at the library, they know all the history of Camden,” Bertie said, but Zara interrupted him.

“Oh Bertie, how kind of you! But I’ve just had a message and I have to leave tomorrow morning for the rendezvous with my friends. There’s been a change of plans.” Zara astonished herself that she blurted that out without thinking it through first. But there. It was said. It was decided.

January 17, 2023 at 8:17 am #6393In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Give me an unusual plot structure for a narrative

One unusual plot structure for a narrative could be a “reverse chronological” structure, where the story begins at the end and works backwards in time, revealing events and information in a non-linear way. Another could be a “choose your own adventure” style, where the reader is presented with a series of choices at different points in the story that determine the direction and outcome of the plot.

How would role playing qualify in terms of plot structure?

Role-playing games (RPGs) can be considered a unique form of plot structure because they are interactive and open-ended. In a traditional RPG, the players take on the roles of characters within a fictional setting and work together to create a shared narrative. The plot structure of an RPG is determined by the actions and decisions of the players, rather than a pre-written script. The game master (GM) creates an overarching plot and a set of rules for the players to follow, but the players’ choices and actions will determine the direction and outcome of the story. This makes the plot structure of an RPG fluid and ever-changing, unlike a traditional linear narrative.

What about “Cloud Atlas” in terms of plot structure?

“Cloud Atlas” is a novel written by David Mitchell that was later adapted into a film. It has a complex and non-linear plot structure, which employs multiple storylines that are set in different time periods and locations, and are connected by recurring themes and motifs. The novel is divided into six nested stories, each set in a different time period and location, that are told in a non-linear fashion. The story begins in the 19th century and then jumps back and forth between the 19th, 20th and 23rd century, and each story is interconnected and interrelated, with characters reappearing in different time periods, the events that happen in one story impacting the others. The novel is also notable for its use of different genres, such as science fiction, historical fiction, and thriller, and the way it explores the themes of destiny, reincarnation, and the power of human connection. The film adaptation also used this structure, with the different stories intertwined and characters reprising their roles in different settings and eras.

Take a story thread made of comments. In each comment is a text about characters in a particular plot, location, action etc. The comments are sequential, but they are not necessarily continuous. It is a mix between Cloud Atlas and RPG plot structures. How do you sort something that’s fundamentally non-linear to present it in an accessible way?

One way to sort and present a story thread made of comments that is fundamentally non-linear, yet accessible, is to group the comments based on their content. For example, you could group the comments by characters, and present them in chronological order of their appearance in the story. Another way could be grouping the comments by location, and present them in chronological order of when the action takes place in that particular location. You could also group comments by the type of action taking place, such as combat, conversation, or puzzle-solving, and present them in chronological order of when they occur in the story.

Another approach could be using visual aids, such as mind maps, timelines, or flowcharts, to help organize and present the information in a clear and easy-to-understand way. For example, you could use a mind map to show how different characters are connected, or a timeline to show the chronology of events. Additionally, you could use labels, such as “character introduction,” “location change,” or “plot twist,” to make it clear to the reader what type of information they can expect in each comment.

It’s also important to keep in mind the audience for which you are organizing the story. It should be easy for them to understand and follow the story, and if it’s a game, you should make sure it’s easy for the players to play and make decisions.

January 14, 2023 at 1:22 pm #6386In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

At the board game, Zara was the first to break character, although Yasmin had been rolling her eyes in silence for quite some time.

“They’re all so young and attractive…”

Yasmin chimed in “Could you add averagely attractive to the prompt? Oh hark at me! Moaning already!”

Xavier was glad at the break, and stretched his arms, leaning back against the chair. “Time for a bio-break guys, all this setting up is taking a lot of time.”

Youssef, who was connected via a stream, started to post emojis of food in the chat. He’d been obviously hungry for a while as usual.

“Ok guys,” said Zara sighing. “That’s settled for today then. Anyway, it’s pretty late for Youssef, let’s resume tomorrow. Meanwhile, I’ll be posting the characters concept art, but don’t hold your breath on that.”

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Brownings of Tetbury

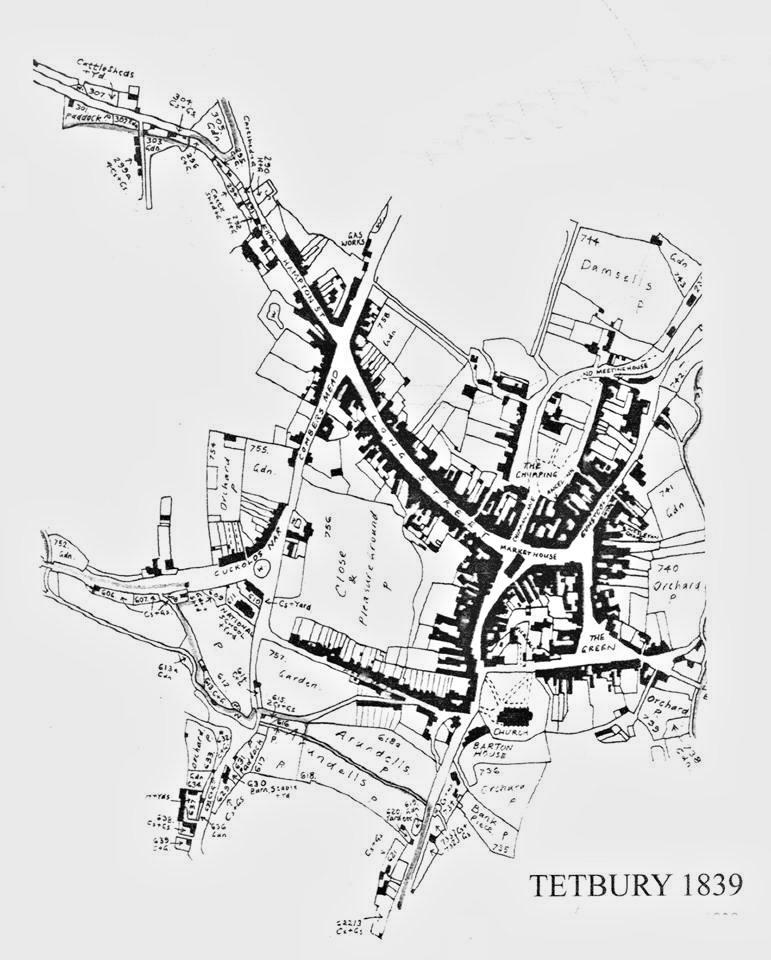

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.