Search Results for 'clothes'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 28, 2022 at 2:29 pm #6261

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Mchewe Estate. 11th July 1931.

Dearest Family,

You say that you would like to know more about our neighbours. Well there is

not much to tell. Kath Wood is very good about coming over to see me. I admire her

very much because she is so capable as well as being attractive. She speaks very

fluent Ki-Swahili and I envy her the way she can carry on a long conversation with the

natives. I am very slow in learning the language possibly because Lamek and the

houseboy both speak basic English.I have very little to do with the Africans apart from the house servants, but I do

run a sort of clinic for the wives and children of our employees. The children suffer chiefly

from sore eyes and worms, and the older ones often have bad ulcers on their legs. All

farmers keep a stock of drugs and bandages.George also does a bit of surgery and last month sewed up the sole of the foot

of a boy who had trodden on the blade of a panga, a sort of sword the Africans use for

hacking down bush. He made an excellent job of it. George tells me that the Africans

have wonderful powers of recuperation. Once in his bachelor days, one of his men was

disembowelled by an elephant. George washed his “guts” in a weak solution of

pot.permang, put them back in the cavity and sewed up the torn flesh and he

recovered.But to get back to the neighbours. We see less of Hicky Wood than of Kath.

Hicky can be charming but is often moody as I believe Irishmen often are.

Major Jones is now at home on his shamba, which he leaves from time to time

for temporary jobs on the district roads. He walks across fairly regularly and we are

always glad to see him for he is a great bearer of news. In this part of Africa there is no

knocking or ringing of doorbells. Front doors are always left open and visitors always

welcome. When a visitor approaches a house he shouts “Hodi”, and the owner of the

house yells “Karibu”, which I believe means “Come near” or approach, and tea is

produced in a matter of minutes no matter what hour of the day it is.

The road that passes all our farms is the only road to the Gold Diggings and

diggers often drop in on the Woods and Major Jones and bring news of the Goldfields.

This news is sometimes about gold but quite often about whose wife is living with

whom. This is a great country for gossip.Major Jones now has his brother Llewyllen living with him. I drove across with

George to be introduced to him. Llewyllen’s health is poor and he looks much older than

his years and very like the portrait of Trader Horn. He has the same emaciated features,

burning eyes and long beard. He is proud of his Welsh tenor voice and often bursts into

song.Both brothers are excellent conversationalists and George enjoys walking over

sometimes on a Sunday for a bit of masculine company. The other day when George

walked across to visit the Joneses, he found both brothers in the shamba and Llew in a

great rage. They had been stooping to inspect a water furrow when Llew backed into a

hornets nest. One furious hornet stung him on the seat and another on the back of his

neck. Llew leapt forward and somehow his false teeth shot out into the furrow and were

carried along by the water. When George arrived Llew had retrieved his teeth but

George swears that, in the commotion, the heavy leather leggings, which Llew always

wears, had swivelled around on his thin legs and were calves to the front.

George has heard that Major Jones is to sell pert of his land to his Swedish brother-in-law, Max Coster, so we will soon have another couple in the neighbourhood.I’ve had a bit of a pantomime here on the farm. On the day we went to Tukuyu,

all our washing was stolen from the clothes line and also our new charcoal iron. George

reported the matter to the police and they sent out a plain clothes policeman. He wears

the long white Arab gown called a Kanzu much in vogue here amongst the African elite

but, alas for secrecy, huge black police boots protrude from beneath the Kanzu and, to

add to this revealing clue, the askari springs to attention and salutes each time I pass by.

Not much hope of finding out the identity of the thief I fear.George’s furrow was entirely successful and we now have water running behind

the kitchen. Our drinking water we get from a lovely little spring on the farm. We boil and

filter it for safety’s sake. I don’t think that is necessary. The furrow water is used for

washing pots and pans and for bath water.Lots of love,

EleanorMchewe Estate. 8th. August 1931

Dearest Family,

I think it is about time I told you that we are going to have a baby. We are both

thrilled about it. I have not seen a Doctor but feel very well and you are not to worry. I

looked it up in my handbook for wives and reckon that the baby is due about February

8th. next year.The announcement came from George, not me! I had been feeling queasy for

days and was waiting for the right moment to tell George. You know. Soft lights and

music etc. However when I was listlessly poking my food around one lunch time

George enquired calmly, “When are you going to tell me about the baby?” Not at all

according to the book! The problem is where to have the baby. February is a very wet

month and the nearest Doctor is over 50 miles away at Tukuyu. I cannot go to stay at

Tukuyu because there is no European accommodation at the hospital, no hotel and no

friend with whom I could stay.George thinks I should go South to you but Capetown is so very far away and I

love my little home here. Also George says he could not come all the way down with

me as he simply must stay here and get the farm on its feet. He would drive me as far

as the railway in Northern Rhodesia. It is a difficult decision to take. Write and tell me what

you think.The days tick by quietly here. The servants are very willing but have to be

supervised and even then a crisis can occur. Last Saturday I was feeling squeamish and

decided not to have lunch. I lay reading on the couch whilst George sat down to a

solitary curry lunch. Suddenly he gave an exclamation and pushed back his chair. I

jumped up to see what was wrong and there, on his plate, gleaming in the curry gravy

were small bits of broken glass. I hurried to the kitchen to confront Lamek with the plate.

He explained that he had dropped the new and expensive bottle of curry powder on

the brick floor of the kitchen. He did not tell me as he thought I would make a “shauri” so

he simply scooped up the curry powder, removed the larger pieces of glass and used

part of the powder for seasoning the lunch.The weather is getting warmer now. It was very cold in June and July and we had

fires in the daytime as well as at night. Now that much of the land has been cleared we

are able to go for pleasant walks in the weekends. My favourite spot is a waterfall on the

Mchewe River just on the boundary of our land. There is a delightful little pool below the

waterfall and one day George intends to stock it with trout.Now that there are more Europeans around to buy meat the natives find it worth

their while to kill an occasional beast. Every now and again a native arrives with a large

bowl of freshly killed beef for sale. One has no way of knowing whether the animal was

healthy and the meat is often still warm and very bloody. I hated handling it at first but am

becoming accustomed to it now and have even started a brine tub. There is no other

way of keeping meat here and it can only be kept in its raw state for a few hours before

going bad. One of the delicacies is the hump which all African cattle have. When corned

it is like the best brisket.See what a housewife I am becoming.

With much love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. Sept.6th. 1931

Dearest Family,

I have grown to love the life here and am sad to think I shall be leaving

Tanganyika soon for several months. Yes I am coming down to have the baby in the

bosom of the family. George thinks it best and so does the doctor. I didn’t mention it

before but I have never recovered fully from the effects of that bad bout of malaria and

so I have been persuaded to leave George and our home and go to the Cape, in the

hope that I shall come back here as fit as when I first arrived in the country plus a really

healthy and bouncing baby. I am torn two ways, I long to see you all – but how I would

love to stay on here.George will drive me down to Northern Rhodesia in early October to catch a

South bound train. I’ll telegraph the date of departure when I know it myself. The road is

very, very bad and the car has been giving a good deal of trouble so, though the baby

is not due until early February, George thinks it best to get the journey over soon as

possible, for the rains break in November and the the roads will then be impassable. It

may take us five or six days to reach Broken Hill as we will take it slowly. I am looking

forward to the drive through new country and to camping out at night.

Our days pass quietly by. George is out on the shamba most of the day. He

goes out before breakfast on weekdays and spends most of the day working with the

men – not only supervising but actually working with his hands and beating the labourers

at their own jobs. He comes to the house for meals and tea breaks. I potter around the

house and garden, sew, mend and read. Lamek continues to be a treasure. he turns out

some surprising dishes. One of his specialities is stuffed chicken. He carefully skins the

chicken removing all bones. He then minces all the chicken meat and adds minced onion

and potatoes. He then stuffs the chicken skin with the minced meat and carefully sews it

together again. The resulting dish is very filling because the boned chicken is twice the

size of a normal one. It lies on its back as round as a football with bloated legs in the air.

Rather repulsive to look at but Lamek is most proud of his accomplishment.

The other day he produced another of his masterpieces – a cooked tortoise. It

was served on a dish covered with parsley and crouched there sans shell but, only too

obviously, a tortoise. I took one look and fled with heaving diaphragm, but George said

it tasted quite good. He tells me that he has had queerer dishes produced by former

cooks. He says that once in his hunting days his cook served up a skinned baby

monkey with its hands folded on its breast. He says it would take a cannibal to eat that

dish.And now for something sad. Poor old Llew died quite suddenly and it was a sad

shock to this tiny community. We went across to the funeral and it was a very simple and

dignified affair. Llew was buried on Joni’s farm in a grave dug by the farm boys. The

body was wrapped in a blanket and bound to some boards and lowered into the

ground. There was no service. The men just said “Good-bye Llew.” and “Sleep well

Llew”, and things like that. Then Joni and his brother-in-law Max, and George shovelled

soil over the body after which the grave was filled in by Joni’s shamba boys. It was a

lovely bright afternoon and I thought how simple and sensible a funeral it was.

I hope you will be glad to have me home. I bet Dad will be holding thumbs that

the baby will be a girl.Very much love,

Eleanor.Note

“There are no letters to my family during the period of Sept. 1931 to June 1932

because during these months I was living with my parents and sister in a suburb of

Cape Town. I had hoped to return to Tanganyika by air with my baby soon after her

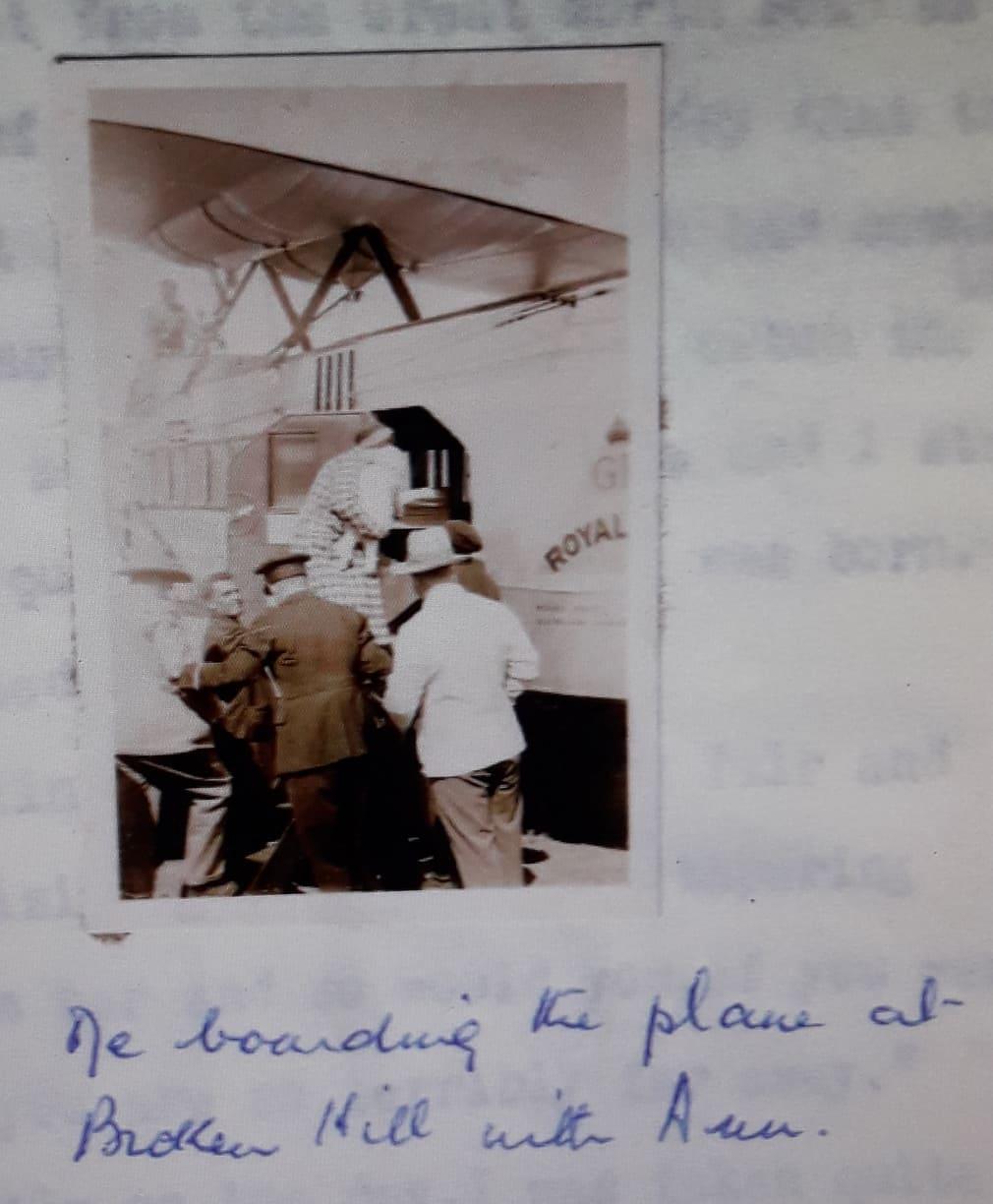

birth in Feb.1932 but the doctor would not permit this.A month before my baby was born, a company called Imperial Airways, had

started the first passenger service between South Africa and England. One of the night

stops was at Mbeya near my husband’s coffee farm, and it was my intention to take the

train to Broken Hill in Northern Rhodesia and to fly from there to Mbeya with my month

old baby. In those days however, commercial flying was still a novelty and the doctor

was not sure that flying at a high altitude might not have an adverse effect upon a young

baby.He strongly advised me to wait until the baby was four months old and I did this

though the long wait was very trying to my husband alone on our farm in Tanganyika,

and to me, cherished though I was in my old home.My story, covering those nine long months is soon told. My husband drove me

down from Mbeya to Broken Hill in NorthernRhodesia. The journey was tedious as the

weather was very hot and dry and the road sandy and rutted, very different from the

Great North road as it is today. The wooden wheel spokes of the car became so dry

that they rattled and George had to bind wet rags around them. We had several

punctures and with one thing and another I was lucky to catch the train.

My parents were at Cape Town station to welcome me and I stayed

comfortably with them, living very quietly, until my baby was born. She arrived exactly

on the appointed day, Feb.8th.I wrote to my husband “Our Charmian Ann is a darling baby. She is very fair and

rather pale and has the most exquisite hands, with long tapering fingers. Daddy

absolutely dotes on her and so would you, if you were here. I can’t bear to think that you

are so terribly far away. Although Ann was born exactly on the day, I was taken quite by

surprise. It was awfully hot on the night before, and before going to bed I had a fancy for

some water melon. The result was that when I woke in the early morning with labour

pains and vomiting I thought it was just an attack of indigestion due to eating too much

melon. The result was that I did not wake Marjorie until the pains were pretty frequent.

She called our next door neighbour who, in his pyjamas, drove me to the nursing home

at breakneck speed. The Matron was very peeved that I had left things so late but all

went well and by nine o’clock, Mother, positively twittering with delight, was allowed to

see me and her first granddaughter . She told me that poor Dad was in such a state of

nerves that he was sick amongst the grapevines. He says that he could not bear to go

through such an anxious time again, — so we will have to have our next eleven in

Tanganyika!”The next four months passed rapidly as my time was taken up by the demands

of my new baby. Dr. Trudy King’s method of rearing babies was then the vogue and I

stuck fanatically to all the rules he laid down, to the intense exasperation of my parents

who longed to cuddle the child.As the time of departure drew near my parents became more and more reluctant

to allow me to face the journey alone with their adored grandchild, so my brother,

Graham, very generously offered to escort us on the train to Broken Hill where he could

put us on the plane for Mbeya.

Mchewe Estate. June 15th 1932

Dearest Family,

You’ll be glad to know that we arrived quite safe and sound and very, very

happy to be home.The train Journey was uneventful. Ann slept nearly all the way.

Graham was very kind and saw to everything. He even sat with the baby whilst I went

to meals in the dining car.We were met at Broken Hill by the Thoms who had arranged accommodation for

us at the hotel for the night. They also drove us to the aerodrome in the morning where

the Airways agent told us that Ann is the first baby to travel by air on this section of the

Cape to England route. The plane trip was very bumpy indeed especially between

Broken Hill and Mpika. Everyone was ill including poor little Ann who sicked up her milk

all over the front of my new coat. I arrived at Mbeya looking a sorry caricature of Radiant

Motherhood. I must have been pale green and the baby was snow white. Under the

circumstances it was a good thing that George did not meet us. We were met instead

by Ken Menzies, the owner of the Mbeya Hotel where we spent the night. Ken was

most fatherly and kind and a good nights rest restored Ann and me to our usual robust

health.Mbeya has greatly changed. The hotel is now finished and can accommodate

fifty guests. It consists of a large main building housing a large bar and dining room and

offices and a number of small cottage bedrooms. It even has electric light. There are

several buildings out at the aerodrome and private houses going up in Mbeya.

After breakfast Ken Menzies drove us out to the farm where we had a warm

welcome from George, who looks well but rather thin. The house was spotless and the

new cook, Abel, had made light scones for tea. George had prepared all sorts of lovely

surprises. There is a new reed ceiling in the living room and a new dresser gay with

willow pattern plates which he had ordered from England. There is also a writing table

and a square table by the door for visitors hats. More personal is a lovely model ship

which George assembled from one of those Hobbie’s kits. It puts the finishing touch to

the rather old world air of our living room.In the bedroom there is a large double bed which George made himself. It has

strips of old car tyres nailed to a frame which makes a fine springy mattress and on top

of this is a thick mattress of kapok.In the kitchen there is a good wood stove which

George salvaged from a Mission dump. It looks a bit battered but works very well. The

new cook is excellent. The only blight is that he will wear rubber soled tennis shoes and

they smell awful. I daren’t hurt his feelings by pointing this out though. Opposite the

kitchen is a new laundry building containing a forty gallon hot water drum and a sink for

washing up. Lovely!George has been working very hard. He now has forty acres of coffee seedlings

planted out and has also found time to plant a rose garden and fruit trees. There are

orange and peach trees, tree tomatoes, paw paws, guavas and berries. He absolutely

adores Ann who has been very good and does not seem at all unsettled by the long

journey.It is absolutely heavenly to be back and I shall be happier than ever now that I

have a baby to play with during the long hours when George is busy on the farm,

Thank you for all your love and care during the many months I was with you. Ann

sends a special bubble for granddad.Your very loving,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate Mbeya July 18th 1932

Dearest Family,

Ann at five months is enchanting. She is a very good baby, smiles readily and is

gaining weight steadily. She doesn’t sleep much during the day but that does not

matter, because, apart from washing her little things, I have nothing to do but attend to

her. She sleeps very well at night which is a blessing as George has to get up very

early to start work on the shamba and needs a good nights rest.

My nights are not so good, because we are having a plague of rats which frisk

around in the bedroom at night. Great big ones that come up out of the long grass in the

gorge beside the house and make cosy homes on our reed ceiling and in the thatch of

the roof.We always have a night light burning so that, if necessary, I can attend to Ann

with a minimum of fuss, and the things I see in that dim light! There are gaps between

the reeds and one night I heard, plop! and there, before my horrified gaze, lay a newly

born hairless baby rat on the floor by the bed, plop, plop! and there lay two more.

Quite dead, poor things – but what a careless mother.I have also seen rats scampering around on the tops of the mosquito nets and

sometimes we have them on our bed. They have a lovely game. They swarm down

the cord from which the mosquito net is suspended, leap onto the bed and onto the

floor. We do not have our net down now the cold season is here and there are few

mosquitoes.Last week a rat crept under Ann’s net which hung to the floor and bit her little

finger, so now I tuck the net in under the mattress though it makes it difficult for me to

attend to her at night. We shall have to get a cat somewhere. Ann’s pram has not yet

arrived so George carries her when we go walking – to her great content.

The native women around here are most interested in Ann. They come to see

her, bearing small gifts, and usually bring a child or two with them. They admire my child

and I admire theirs and there is an exchange of gifts. They produce a couple of eggs or

a few bananas or perhaps a skinny fowl and I hand over sugar, salt or soap as they

value these commodities. The most lavish gift went to the wife of Thomas our headman,

who produced twin daughters in the same week as I had Ann.Our neighbours have all been across to welcome me back and to admire the

baby. These include Marion Coster who came out to join her husband whilst I was in

South Africa. The two Hickson-Wood children came over on a fat old white donkey.

They made a pretty picture sitting astride, one behind the other – Maureen with her arms

around small Michael’s waist. A native toto led the donkey and the children’ s ayah

walked beside it.It is quite cold here now but the sun is bright and the air dry. The whole

countryside is beautifully green and we are a very happy little family.Lots and lots of love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate August 11th 1932

Dearest Family,

George has been very unwell for the past week. He had a nasty gash on his

knee which went septic. He had a swelling in the groin and a high temperature and could

not sleep at night for the pain in his leg. Ann was very wakeful too during the same

period, I think she is teething. I luckily have kept fit though rather harassed. Yesterday the

leg looked so inflamed that George decided to open up the wound himself. he made

quite a big cut in exactly the right place. You should have seen the blackish puss

pouring out.After he had thoroughly cleaned the wound George sewed it up himself. he has

the proper surgical needles and gut. He held the cut together with his left hand and

pushed the needle through the flesh with his right. I pulled the needle out and passed it

to George for the next stitch. I doubt whether a surgeon could have made a neater job

of it. He is still confined to the couch but today his temperature is normal. Some

husband!The previous week was hectic in another way. We had a visit from lions! George

and I were having supper about 8.30 on Tuesday night when the back verandah was

suddenly invaded by women and children from the servants quarters behind the kitchen.

They were all yelling “Simba, Simba.” – simba means lions. The door opened suddenly

and the houseboy rushed in to say that there were lions at the huts. George got up

swiftly, fetched gun and ammunition from the bedroom and with the houseboy carrying

the lamp, went off to investigate. I remained at the table, carrying on with my supper as I

felt a pioneer’s wife should! Suddenly something big leapt through the open window

behind me. You can imagine what I thought! I know now that it is quite true to say one’s

hair rises when one is scared. However it was only Kelly, our huge Irish wolfhound,

taking cover.George returned quite soon to say that apparently the commotion made by the

women and children had frightened the lions off. He found their tracks in the soft earth

round the huts and a bag of maize that had been playfully torn open but the lions had

moved on.Next day we heard that they had moved to Hickson-Wood’s shamba. Hicky

came across to say that the lions had jumped over the wall of his cattle boma and killed

both his white Muskat riding donkeys.

He and a friend sat up all next night over the remains but the lions did not return to

the kill.Apart from the little set back last week, Ann is blooming. She has a cap of very

fine fair hair and clear blue eyes under straight brow. She also has lovely dimples in both

cheeks. We are very proud of her.Our neighbours are picking coffee but the crops are small and the price is low. I

am amazed that they are so optimistic about the future. No one in these parts ever

seems to grouse though all are living on capital. They all say “Well if the worst happens

we can always go up to the Lupa Diggings.”Don’t worry about us, we have enough to tide us over for some time yet.

Much love to all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 28th Sept. 1932

Dearest Family,

News! News! I’m going to have another baby. George and I are delighted and I

hope it will be a boy this time. I shall be able to have him at Mbeya because things are

rapidly changing here. Several German families have moved to Mbeya including a

German doctor who means to build a hospital there. I expect he will make a very good

living because there must now be some hundreds of Europeans within a hundred miles

radius of Mbeya. The Europeans are mostly British or German but there are also

Greeks and, I believe, several other nationalities are represented on the Lupa Diggings.

Ann is blooming and developing according to the Book except that she has no

teeth yet! Kath Hickson-Wood has given her a very nice high chair and now she has

breakfast and lunch at the table with us. Everything within reach goes on the floor to her

amusement and my exasperation!You ask whether we have any Church of England missionaries in our part. No we

haven’t though there are Lutheran and Roman Catholic Missions. I have never even

heard of a visiting Church of England Clergyman to these parts though there are babies

in plenty who have not been baptised. Jolly good thing I had Ann Christened down

there.The R.C. priests in this area are called White Fathers. They all have beards and

wear white cassocks and sun helmets. One, called Father Keiling, calls around frequently.

Though none of us in this area is Catholic we take it in turn to put him up for the night. The

Catholic Fathers in their turn are most hospitable to travellers regardless of their beliefs.

Rather a sad thing has happened. Lucas our old chicken-boy is dead. I shall miss

his toothy smile. George went to the funeral and fired two farewell shots from his rifle

over the grave – a gesture much appreciated by the locals. Lucas in his day was a good

hunter.Several of the locals own muzzle loading guns but the majority hunt with dogs

and spears. The dogs wear bells which make an attractive jingle but I cannot bear the

idea of small antelope being run down until they are exhausted before being clubbed of

stabbed to death. We seldom eat venison as George does not care to shoot buck.

Recently though, he shot an eland and Abel rendered down the fat which is excellent for

cooking and very like beef fat.Much love to all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. P.O.Mbeya 21st November 1932

Dearest Family,

George has gone off to the Lupa for a week with John Molteno. John came up

here with the idea of buying a coffee farm but he has changed his mind and now thinks of

staking some claims on the diggings and also setting up as a gold buyer.Did I tell you about his arrival here? John and George did some elephant hunting

together in French Equatorial Africa and when John heard that George had married and

settled in Tanganyika, he also decided to come up here. He drove up from Cape Town

in a Baby Austin and arrived just as our labourers were going home for the day. The little

car stopped half way up our hill and John got out to investigate. You should have heard

the astonished exclamations when John got out – all 6 ft 5 ins. of him! He towered over

the little car and even to me it seemed impossible for him to have made the long

journey in so tiny a car.Kath Wood has been over several times lately. She is slim and looks so right in

the shirt and corduroy slacks she almost always wears. She was here yesterday when

the shamba boy, digging in the front garden, unearthed a large earthenware cooking pot,

sealed at the top. I was greatly excited and had an instant mental image of fabulous

wealth. We made the boy bring the pot carefully on to the verandah and opened it in

happy anticipation. What do you think was inside? Nothing but a grinning skull! Such a

treat for a pregnant female.We have a tree growing here that had lovely straight branches covered by a

smooth bark. I got the garden boy to cut several of these branches of a uniform size,

peeled off the bark and have made Ann a playpen with the poles which are much like

broom sticks. Now I can leave her unattended when I do my chores. The other morning

after breakfast I put Ann in her playpen on the verandah and gave her a piece of toast

and honey to keep her quiet whilst I laundered a few of her things. When I looked out a

little later I was horrified to see a number of bees buzzing around her head whilst she

placidly concentrated on her toast. I made a rapid foray and rescued her but I still don’t

know whether that was the thing to do.We all send our love,

Eleanor.Mbeya Hospital. April 25th. 1933

Dearest Family,

Here I am, installed at the very new hospital, built by Dr Eckhardt, awaiting the

arrival of the new baby. George has gone back to the farm on foot but will walk in again

to spend the weekend with us. Ann is with me and enjoys the novelty of playing with

other children. The Eckhardts have two, a pretty little girl of two and a half and a very fair

roly poly boy of Ann’s age. Ann at fourteen months is very active. She is quite a little girl

now with lovely dimples. She walks well but is backward in teething.George, Ann and I had a couple of days together at the hotel before I moved in

here and several of the local women visited me and have promised to visit me in

hospital. The trip from farm to town was very entertaining if not very comfortable. There

is ten miles of very rough road between our farm and Utengule Mission and beyond the

Mission there is a fair thirteen or fourteen mile road to Mbeya.As we have no car now the doctor’s wife offered to drive us from the Mission to

Mbeya but she would not risk her car on the road between the Mission and our farm.

The upshot was that I rode in the Hickson-Woods machila for that ten mile stretch. The

machila is a canopied hammock, slung from a bamboo pole, in which I reclined, not too

comfortably in my unwieldy state, with Ann beside me or sometime straddling me. Four

of our farm boys carried the machila on their shoulders, two fore and two aft. The relief

bearers walked on either side. There must have been a dozen in all and they sang a sort

of sea shanty song as they walked. One man would sing a verse and the others took up

the chorus. They often improvise as they go. They moaned about my weight (at least

George said so! I don’t follow Ki-Swahili well yet) and expressed the hope that I would

have a son and that George would reward them handsomely.George and Kelly, the dog, followed close behind the machila and behind

George came Abel our cook and his wife and small daughter Annalie, all in their best

attire. The cook wore a palm beach suit, large Terai hat and sunglasses and two colour

shoes and quite lent a tone to the proceedings! Right at the back came the rag tag and

bobtail who joined the procession just for fun.Mrs Eckhardt was already awaiting us at the Mission when we arrived and we had

an uneventful trip to the Mbeya Hotel.During my last week at the farm I felt very tired and engaged the cook’s small

daughter, Annalie, to amuse Ann for an hour after lunch so that I could have a rest. They

played in the small verandah room which adjoins our bedroom and where I keep all my

sewing materials. One afternoon I was startled by a scream from Ann. I rushed to the

room and found Ann with blood steaming from her cheek. Annalie knelt beside her,

looking startled and frightened, with my embroidery scissors in her hand. She had cut off

half of the long curling golden lashes on one of Ann’s eyelids and, in trying to finish the

job, had cut off a triangular flap of skin off Ann’s cheek bone.I called Abel, the cook, and demanded that he should chastise his daughter there and

then and I soon heard loud shrieks from behind the kitchen. He spanked her with a

bamboo switch but I am sure not as well as she deserved. Africans are very tolerant

towards their children though I have seen husbands and wives fighting furiously.

I feel very well but long to have the confinement over.Very much love,

Eleanor.Mbeya Hospital. 2nd May 1933.

Dearest Family,

Little George arrived at 7.30 pm on Saturday evening 29 th. April. George was

with me at the time as he had walked in from the farm for news, and what a wonderful bit

of luck that was. The doctor was away on a case on the Diggings and I was bathing Ann

with George looking on, when the pains started. George dried Ann and gave her

supper and put her to bed. Afterwards he sat on the steps outside my room and a

great comfort it was to know that he was there.The confinement was short but pretty hectic. The Doctor returned to the Hospital

just in time to deliver the baby. He is a grand little boy, beautifully proportioned. The

doctor says he has never seen a better formed baby. He is however rather funny

looking just now as his head is, very temporarily, egg shaped. He has a shock of black

silky hair like a gollywog and believe it or not, he has a slight black moustache.

George came in, looked at the baby, looked at me, and we both burst out

laughing. The doctor was shocked and said so. He has no sense of humour and couldn’t

understand that we, though bursting with pride in our son, could never the less laugh at

him.Friends in Mbeya have sent me the most gorgeous flowers and my room is

transformed with delphiniums, roses and carnations. The room would be very austere

without the flowers. Curtains, bedspread and enamelware, walls and ceiling are all

snowy white.George hired a car and took Ann home next day. I have little George for

company during the day but he is removed at night. I am longing to get him home and

away from the German nurse who feeds him on black tea when he cries. She insists that

tea is a medicine and good for him.Much love from a proud mother of two.

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate 12May 1933

Dearest Family,

We are all together at home again and how lovely it feels. Even the house

servants seem pleased. The boy had decorated the lounge with sprays of

bougainvillaea and Abel had backed one of his good sponge cakes.Ann looked fat and rosy but at first was only moderately interested in me and the

new baby but she soon thawed. George is good with her and will continue to dress Ann

in the mornings and put her to bed until I am satisfied with Georgie.He, poor mite, has a nasty rash on face and neck. I am sure it is just due to that

tea the nurse used to give him at night. He has lost his moustache and is fast loosing his

wild black hair and emerging as quite a handsome babe. He is a very masculine looking

infant with much more strongly marked eyebrows and a larger nose that Ann had. He is

very good and lies quietly in his basket even when awake.George has been making a hatching box for brown trout ova and has set it up in

a small clear stream fed by a spring in readiness for the ova which is expected from

South Africa by next weeks plane. Some keen fishermen from Mbeya and the District

have clubbed together to buy the ova. The fingerlings are later to be transferred to

streams in Mbeya and Tukuyu Districts.I shall now have my hands full with the two babies and will not have much time for the

garden, or I fear, for writing very long letters. Remember though, that no matter how

large my family becomes, I shall always love you as much as ever.Your affectionate,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 14th June 1933

Dearest Family,

The four of us are all well but alas we have lost our dear Kelly. He was rather a

silly dog really, although he grew so big he retained all his puppy ways but we were all

very fond of him, especially George because Kelly attached himself to George whilst I

was away having Ann and from that time on he was George’s shadow. I think he had

some form of biliary fever. He died stretched out on the living room couch late last night,

with George sitting beside him so that he would not feel alone.The children are growing fast. Georgie is a darling. He now has a fluff of pale

brown hair and his eyes are large and dark brown. Ann is very plump and fair.

We have had several visitors lately. Apart from neighbours, a car load of diggers

arrived one night and John Molteno and his bride were here. She is a very attractive girl

but, I should say, more suited to life in civilisation than in this back of beyond. She has

gone out to the diggings with her husband and will have to walk a good stretch of the fifty

or so miles.The diggers had to sleep in the living room on the couch and on hastily erected

camp beds. They arrived late at night and left after breakfast next day. One had half a

beard, the other side of his face had been forcibly shaved in the bar the night before.your affectionate,

EleanorMchewe Estate. August 10 th. 1933

Dearest Family,

George is away on safari with two Indian Army officers. The money he will get for

his services will be very welcome because this coffee growing is a slow business, and

our capitol is rapidly melting away. The job of acting as White Hunter was unexpected

or George would not have taken on the job of hatching the ova which duly arrived from

South Africa.George and the District Commissioner, David Pollock, went to meet the plane

by which the ova had been consigned but the pilot knew nothing about the package. It

came to light in the mail bag with the parcels! However the ova came to no harm. David

Pollock and George brought the parcel to the farm and carefully transferred the ova to

the hatching box. It was interesting to watch the tiny fry hatch out – a process which took

several days. Many died in the process and George removed the dead by sucking

them up in a glass tube.When hatched, the tiny fry were fed on ant eggs collected by the boys. I had to

take over the job of feeding and removing the dead when George left on safari. The fry

have to be fed every four hours, like the baby, so each time I have fed Georgie. I hurry

down to feed the trout.The children are very good but keep me busy. Ann can now say several words

and understands more. She adores Georgie. I long to show them off to you.Very much love

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. October 27th 1933

Dear Family,

All just over flu. George and Ann were very poorly. I did not fare so badly and

Georgie came off best. He is on a bottle now.There was some excitement here last Wednesday morning. At 6.30 am. I called

for boiling water to make Georgie’s food. No water arrived but muffled shouting and the

sound of blows came from the kitchen. I went to investigate and found a fierce fight in

progress between the house boy and the kitchen boy. In my efforts to make them stop

fighting I went too close and got a sharp bang on the mouth with the edge of an

enamelled plate the kitchen boy was using as a weapon. My teeth cut my lip inside and

the plate cut it outside and blood flowed from mouth to chin. The boys were petrified.

By the time I had fed Georgie the lip was stiff and swollen. George went in wrath

to the kitchen and by breakfast time both house boy and kitchen boy had swollen faces

too. Since then I have a kettle of boiling water to hand almost before the words are out

of my mouth. I must say that the fight was because the house boy had clouted the

kitchen boy for keeping me waiting! In this land of piece work it is the job of the kitchen

boy to light the fire and boil the kettle but the houseboy’s job to carry the kettle to me.

I have seen little of Kath Wood or Marion Coster for the past two months. Major

Jones is the neighbour who calls most regularly. He has a wireless set and calls on all of

us to keep us up to date with world as well as local news. He often brings oranges for

Ann who adores him. He is a very nice person but no oil painting and makes no effort to

entertain Ann but she thinks he is fine. Perhaps his monocle appeals to her.George has bought a six foot long galvanised bath which is a great improvement

on the smaller oval one we have used until now. The smaller one had grown battered

from much use and leaks like a sieve. Fortunately our bathroom has a cement floor,

because one had to fill the bath to the brim and then bath extremely quickly to avoid

being left high and dry.Lots and lots of love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. P.O. Mbeya 1st December 1933

Dearest Family,

Ann has not been well. We think she has had malaria. She has grown a good

deal lately and looks much thinner and rather pale. Georgie is thriving and has such

sparkling brown eyes and a ready smile. He and Ann make a charming pair, one so fair

and the other dark.The Moltenos’ spent a few days here and took Georgie and me to Mbeya so

that Georgie could be vaccinated. However it was an unsatisfactory trip because the

doctor had no vaccine.George went to the Lupa with the Moltenos and returned to the farm in their Baby

Austin which they have lent to us for a week. This was to enable me to go to Mbeya to

have a couple of teeth filled by a visiting dentist.We went to Mbeya in the car on Saturday. It was quite a squash with the four of

us on the front seat of the tiny car. Once George grabbed the babies foot instead of the

gear knob! We had Georgie vaccinated at the hospital and then went to the hotel where

the dentist was installed. Mr Dare, the dentist, had few instruments and they were very

tarnished. I sat uncomfortably on a kitchen chair whilst he tinkered with my teeth. He filled

three but two of the fillings came out that night. This meant another trip to Mbeya in the

Baby Austin but this time they seem all right.The weather is very hot and dry and the garden a mess. We are having trouble

with the young coffee trees too. Cut worms are killing off seedlings in the nursery and

there is a borer beetle in the planted out coffee.George bought a large grey donkey from some wandering Masai and we hope

the children will enjoy riding it later on.Very much love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 14th February 1934.

Dearest Family,

You will be sorry to hear that little Ann has been very ill, indeed we were terribly

afraid that we were going to lose her. She enjoyed her birthday on the 8th. All the toys

you, and her English granny, sent were unwrapped with such delight. However next

day she seemed listless and a bit feverish so I tucked her up in bed after lunch. I dosed

her with quinine and aspirin and she slept fitfully. At about eleven o’clock I was

awakened by a strange little cry. I turned up the night light and was horrified to see that

Ann was in a convulsion. I awakened George who, as always in an emergency, was

perfectly calm and practical. He filled the small bath with very warm water and emersed

Ann in it, placing a cold wet cloth on her head. We then wrapped her in blankets and

gave her an enema and she settled down to sleep. A few hours later we had the same

thing over again.At first light we sent a runner to Mbeya to fetch the doctor but waited all day in

vain and in the evening the runner returned to say that the doctor had gone to a case on

the diggings. Ann had been feverish all day with two or three convulsions. Neither

George or I wished to leave the bedroom, but there was Georgie to consider, and in

the afternoon I took him out in the garden for a while whilst George sat with Ann.

That night we both sat up all night and again Ann had those wretched attacks of

convulsions. George and I were worn out with anxiety by the time the doctor arrived the

next afternoon. Ann had not been able to keep down any quinine and had had only

small sips of water since the onset of the attack.The doctor at once diagnosed the trouble as malaria aggravated by teething.

George held Ann whilst the Doctor gave her an injection. At the first attempt the needle

bent into a bow, George was furious! The second attempt worked and after a few hours

Ann’s temperature dropped and though she was ill for two days afterwards she is now

up and about. She has also cut the last of her baby teeth, thank God. She looks thin and

white, but should soon pick up. It has all been a great strain to both of us. Georgie

behaved like an angel throughout. He played happily in his cot and did not seem to

sense any tension as people say, babies do. Our baby was cheerful and not at all

subdued.This is the rainy season and it is a good thing that some work has been done on

our road or the doctor might not have got through.Much love to all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 1st October 1934

Dearest Family,

We are all well now, thank goodness, but last week Georgie gave us such a

fright. I was sitting on the verandah, busy with some sewing and not watching Ann and

Georgie, who were trying to reach a bunch of bananas which hung on a rope from a

beam of the verandah. Suddenly I heard a crash, Georgie had fallen backward over the

edge of the verandah and hit the back of his head on the edge of the brick furrow which

carries away the rainwater. He lay flat on his back with his arms spread out and did not

move or cry. When I picked him up he gave a little whimper, I carried him to his cot and

bathed his face and soon he began sitting up and appeared quite normal. The trouble

began after he had vomited up his lunch. He began to whimper and bang his head

against the cot.George and I were very worried because we have no transport so we could not

take Georgie to the doctor and we could not bear to go through again what we had gone

through with Ann earlier in the year. Then, in the late afternoon, a miracle happened. Two

men George hardly knew, and complete strangers to me, called in on their way from the

diggings to Mbeya and they kindly drove Georgie and me to the hospital. The Doctor

allowed me to stay with Georgie and we spent five days there. Luckily he responded to

treatment and is now as alive as ever. Children do put years on one!There is nothing much else to report. We have a new vegetable garden which is

doing well but the earth here is strange. Gardens seem to do well for two years but by

that time the soil is exhausted and one must move the garden somewhere else. The

coffee looks well but it will be another year before we can expect even a few bags of

coffee and prices are still low. Anyway by next year George should have some good

return for all his hard work.Lots of love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. November 4th 1934

Dearest Family,

George is home from his White Hunting safari looking very sunburnt and well.

The elderly American, who was his client this time, called in here at the farm to meet me

and the children. It is amazing what spirit these old lads have! This one looked as though

he should be thinking in terms of slippers and an armchair but no, he thinks in terms of

high powered rifles with telescopic sights.It is lovely being together again and the children are delighted to have their Dad

home. Things are always exciting when George is around. The day after his return

George said at breakfast, “We can’t go on like this. You and the kids never get off the

shamba. We’ll simply have to get a car.” You should have heard the excitement. “Get a

car Daddy?’” cried Ann jumping in her chair so that her plaits bounced. “Get a car

Daddy?” echoed Georgie his brown eyes sparkling. “A car,” said I startled, “However

can we afford one?”“Well,” said George, “on my way back from Safari I heard that a car is to be sold

this week at the Tukuyu Court, diseased estate or bankruptcy or something, I might get it

cheap and it is an A.C.” The name meant nothing to me, but George explained that an

A.C. is first cousin to a Rolls Royce.So off he went to the sale and next day the children and I listened all afternoon for

the sound of an approaching car. We had many false alarms but, towards evening we

heard what appeared to be the roar of an aeroplane engine. It was the A.C. roaring her

way up our steep hill with a long plume of steam waving gaily above her radiator.

Out jumped my beaming husband and in no time at all, he was showing off her

points to an admiring family. Her lines are faultless and seats though worn are most

comfortable. She has a most elegant air so what does it matter that the radiator leaks like

a sieve, her exhaust pipe has broken off, her tyres are worn almost to the canvas and

she has no windscreen. She goes, and she cost only five pounds.Next afternoon George, the kids and I piled into the car and drove along the road

on lookout for guinea fowl. All went well on the outward journey but on the homeward

one the poor A.C. simply gasped and died. So I carried the shot gun and George

carried both children and we trailed sadly home. This morning George went with a bunch

of farmhands and brought her home. Truly temperamental, she came home literally

under her own steam.George now plans to get a second hand engine and radiator for her but it won’t

be an A.C. engine. I think she is the only one of her kind in the country.

I am delighted to hear, dad, that you are sending a bridle for Joseph for

Christmas. I am busy making a saddle out of an old piece of tent canvas stuffed with

kapok, some webbing and some old rug straps. A car and a riding donkey! We’re

definitely carriage folk now.Lots of love to all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 28th December 1934

Dearest Family,

Thank you for the wonderful Christmas parcel. My frock is a splendid fit. George

declares that no one can knit socks like Mummy and the children love their toys and new

clothes.Joseph, the donkey, took his bit with an air of bored resignation and Ann now

rides proudly on his back. Joseph is a big strong animal with the looks and disposition of

a mule. he will not go at all unless a native ‘toto’ walks before him and when he does go

he wears a pained expression as though he were carrying fourteen stone instead of

Ann’s fly weight. I walk beside the donkey carrying Georgie and our cat, ‘Skinny Winnie’,

follows behind. Quite a cavalcade. The other day I got so exasperated with Joseph that

I took Ann off and I got on. Joseph tottered a few paces and sat down! to the huge

delight of our farm labourers who were going home from work. Anyway, one good thing,

the donkey is so lazy that there is little chance of him bolting with Ann.The Moltenos spent Christmas with us and left for the Lupa Diggings yesterday.

They arrived on the 22nd. with gifts for the children and chocolates and beer. That very

afternoon George and John Molteno left for Ivuna, near Lake Ruckwa, to shoot some

guinea fowl and perhaps a goose for our Christmas dinner. We expected the menfolk

back on Christmas Eve and Anne and I spent a busy day making mince pies and

sausage rolls. Why I don’t know, because I am sure Abel could have made them better.

We decorated the Christmas tree and sat up very late but no husbands turned up.

Christmas day passed but still no husbands came. Anne, like me, is expecting a baby

and we both felt pretty forlorn and cross. Anne was certain that they had been caught up

in a party somewhere and had forgotten all about us and I must say when Boxing Day

went by and still George and John did not show up I felt ready to agree with her.

They turned up towards evening and explained that on the homeward trip the car

had bogged down in the mud and that they had spent a miserable Christmas. Anne

refused to believe their story so George, to prove their case, got the game bag and

tipped the contents on to the dining room table. Out fell several guinea fowl, long past

being edible, followed by a large goose so high that it was green and blue where all the

feathers had rotted off.The stench was too much for two pregnant girls. I shot out of the front door

closely followed by Anne and we were both sick in the garden.I could not face food that evening but Anne is made of stronger stuff and ate her

belated Christmas dinner with relish.I am looking forward enormously to having Marjorie here with us. She will be able

to carry back to you an eyewitness account of our home and way of life.Much love to you all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 5th January 1935

Dearest Family,

You cannot imagine how lovely it is to have Marjorie here. She came just in time

because I have had pernicious vomiting and have lost a great deal of weight and she

took charge of the children and made me spend three days in hospital having treatment.

George took me to the hospital on the afternoon of New Years Eve and decided

to spend the night at the hotel and join in the New Years Eve celebrations. I had several

visitors at the hospital that evening and George actually managed to get some imported

grapes for me. He returned to the farm next morning and fetched me from the hospital

four days later. Of course the old A.C. just had to play up. About half way home the

back axle gave in and we had to send a passing native some miles back to a place

called Mbalizi to hire a lorry from a Greek trader to tow us home to the farm.

The children looked well and were full of beans. I think Marjorie was thankful to

hand them over to me. She is delighted with Ann’s motherly little ways but Georgie she

calls “a really wild child”. He isn’t, just has such an astonishing amount of energy and is

always up to mischief. Marjorie brought us all lovely presents. I am so thrilled with my

sewing machine. It may be an old model but it sews marvellously. We now have an

Alsatian pup as well as Joseph the donkey and the two cats.Marjorie had a midnight encounter with Joseph which gave her quite a shock but

we had a good laugh about it next day. Some months ago George replaced our wattle

and daub outside pit lavatory by a substantial brick one, so large that Joseph is being

temporarily stabled in it at night. We neglected to warn Marj about this and one night,

storm lamp in hand, she opened the door and Joseph walked out braying his thanks.

I am afraid Marjorie is having a quiet time, a shame when the journey from Cape

Town is so expensive. The doctor has told me to rest as much as I can, so it is

impossible for us to take Marj on sight seeing trips.I hate to think that she will be leaving in ten days time.

Much love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 18th February 1935

Dearest Family,

You must be able to visualise our life here quite well now that Marj is back and

has no doubt filled in all the details I forget to mention in my letters. What a journey we

had in the A.C. when we took her to the plane. George, the children and I sat in front and

Marj sat behind with numerous four gallon tins of water for the insatiable radiator. It was

raining and the canvas hood was up but part of the side flaps are missing and as there is

no glass in the windscreen the rain blew in on us. George got fed up with constantly

removing the hot radiator cap so simply stuffed a bit of rag in instead. When enough

steam had built up in the radiator behind the rag it blew out and we started all over again.

The car still roars like an aeroplane engine and yet has little power so that George sent

gangs of boys to the steep hills between the farm and the Mission to give us a push if

necessary. Fortunately this time it was not, and the boys cheered us on our way. We

needed their help on the homeward journey however.George has now bought an old Chev engine which he means to install before I

have to go to hospital to have my new baby. It will be quite an engineering feet as

George has few tools.I am sorry to say that I am still not well, something to do with kidneys or bladder.

George bought me some pills from one of the several small shops which have opened

in Mbeya and Ann is most interested in the result. She said seriously to Kath Wood,

“Oh my Mummy is a very clever Mummy. She can do blue wee and green wee as well

as yellow wee.” I simply can no longer manage the children without help and have

engaged the cook’s wife, Janey, to help. The children are by no means thrilled. I plead in

vain that I am not well enough to go for walks. Ann says firmly, “Ann doesn’t want to go

for a walk. Ann will look after you.” Funny, though she speaks well for a three year old,

she never uses the first person. Georgie say he would much rather walk with

Keshokutwa, the kitchen boy. His name by the way, means day-after-tomorrow and it

suits him down to the ground, Kath Wood walks over sometimes with offers of help and Ann will gladly go walking with her but Georgie won’t. He on the other hand will walk with Anne Molteno

and Ann won’t. They are obstinate kids. Ann has developed a very fertile imagination.

She has probably been looking at too many of those nice women’s magazines you

sent. A few days ago she said, “You are sick Mummy, but Ann’s got another Mummy.

She’s not sick, and my other mummy (very smugly) has lovely golden hair”. This

morning’ not ten minutes after I had dressed her, she came in with her frock wet and

muddy. I said in exasperation, “Oh Ann, you are naughty.” To which she instantly

returned, “My other Mummy doesn’t think I am naughty. She thinks I am very nice.” It

strikes me I shall have to get better soon so that I can be gay once more and compete

with that phantom golden haired paragon.We had a very heavy storm over the farm last week. There was heavy rain with

hail which stripped some of the coffee trees and the Mchewe River flooded and the

water swept through the lower part of the shamba. After the water had receded George

picked up a fine young trout which had been stranded. This was one of some he had

put into the river when Georgie was a few months old.The trials of a coffee farmer are legion. We now have a plague of snails. They

ring bark the young trees and leave trails of slime on the glossy leaves. All the ring

barked trees will have to be cut right back and this is heartbreaking as they are bearing

berries for the first time. The snails are collected by native children, piled upon the

ground and bashed to a pulp which gives off a sickening stench. I am sorry for the local

Africans. Locusts ate up their maize and now they are losing their bean crop to the snails.Lots of love, Eleanor

January 28, 2022 at 1:10 pm #6260In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

- “The letters of Eleanor Dunbar Leslie to her parents and her sister in South Africa

concerning her life with George Gilman Rushby of Tanganyika, and the trials and

joys of bringing up a family in pioneering conditions.

These letters were transcribed from copies of letters typed by Eleanor Rushby from

the originals which were in the estate of Marjorie Leslie, Eleanor’s sister. Eleanor

kept no diary of her life in Tanganyika, so these letters were the living record of an

important part of her life.Prelude

Having walked across Africa from the East coast to Ubangi Shauri Chad

in French Equatorial Africa, hunting elephant all the way, George Rushby

made his way down the Congo to Leopoldville. He then caught a ship to

Europe and had a holiday in Brussels and Paris before visiting his family

in England. He developed blackwater fever and was extremely ill for a

while. When he recovered he went to London to arrange his return to

Africa.Whilst staying at the Overseas Club he met Eileen Graham who had come

to England from Cape Town to study music. On hearing that George was

sailing for Cape Town she arranged to introduce him to her friend

Eleanor Dunbar Leslie. “You’ll need someone lively to show you around,”

she said. “She’s as smart as paint, a keen mountaineer, a very good school

teacher, and she’s attractive. You can’t miss her, because her father is a

well known Cape Town Magistrate. And,” she added “I’ve already written

and told her what ship you are arriving on.”Eleanor duly met the ship. She and George immediately fell in love.

Within thirty six hours he had proposed marriage and was accepted

despite the misgivings of her parents. As she was under contract to her

High School, she remained in South Africa for several months whilst

George headed for Tanganyika looking for a farm where he could build

their home.These details are a summary of chapter thirteen of the Biography of

George Gilman Rushby ‘The Hunter is Death “ by T.V.Bulpin.Dearest Marj,

Terrifically exciting news! I’ve just become engaged to an Englishman whom I

met last Monday. The result is a family upheaval which you will have no difficulty in

imagining!!The Aunts think it all highly romantic and cry in delight “Now isn’t that just like our

El!” Mummy says she doesn’t know what to think, that anyway I was always a harum

scarum and she rather expected something like this to happen. However I know that

she thinks George highly attractive. “Such a nice smile and gentle manner, and such

good hands“ she murmurs appreciatively. “But WHY AN ELEPHANT HUNTER?” she

ends in a wail, as though elephant hunting was an unmentionable profession.

Anyway I don’t think so. Anyone can marry a bank clerk or a lawyer or even a

millionaire – but whoever heard of anyone marrying anyone as exciting as an elephant

hunter? I’m thrilled to bits.Daddy also takes a dim view of George’s profession, and of George himself as

a husband for me. He says that I am so impulsive and have such wild enthusiasms that I

need someone conservative and steady to give me some serenity and some ballast.

Dad says George is a handsome fellow and a good enough chap he is sure, but

he is obviously a man of the world and hints darkly at a possible PAST. George says

he has nothing of the kind and anyway I’m the first girl he has asked to marry him. I don’t

care anyway, I’d gladly marry him tomorrow, but Dad has other ideas.He sat in his armchair to deliver his verdict, wearing the same look he must wear

on the bench. If we marry, and he doesn’t think it would be a good thing, George must

buy a comfortable house for me in Central Africa where I can stay safely when he goes

hunting. I interrupted to say “But I’m going too”, but dad snubbed me saying that in no

time at all I’ll have a family and one can’t go dragging babies around in the African Bush.”

George takes his lectures with surprising calm. He says he can see Dad’s point of

view much better than I can. He told the parents today that he plans to buy a small

coffee farm in the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika and will build a cosy cottage which

will be a proper home for both of us, and that he will only hunt occasionally to keep the

pot boiling.Mummy, of course, just had to spill the beans. She said to George, “I suppose

you know that Eleanor knows very little about house keeping and can’t cook at all.” a fact

that I was keeping a dark secret. But George just said, “Oh she won’t have to work. The

boys do all that sort of thing. She can lie on a couch all day and read if she likes.” Well

you always did say that I was a “Lily of the field,” and what a good thing! If I were one of

those terribly capable women I’d probably die of frustration because it seems that

African house boys feel that they have lost face if their Memsahibs do anything but the

most gracious chores.George is absolutely marvellous. He is strong and gentle and awfully good

looking too. He is about 5 ft 10 ins tall and very broad. He wears his curly brown hair cut

very short and has a close clipped moustache. He has strongly marked eyebrows and

very striking blue eyes which sometimes turn grey or green. His teeth are strong and

even and he has a quiet voice.I expect all this sounds too good to be true, but come home quickly and see for

yourself. George is off to East Africa in three weeks time to buy our farm. I shall follow as

soon as he has bought it and we will be married in Dar es Salaam.Dad has taken George for a walk “to get to know him” and that’s why I have time

to write such a long screed. They should be back any minute now and I must fly and

apply a bit of glamour.Much love my dear,

your jubilant

EleanorS.S.Timavo. Durban. 28th.October. 1930.

Dearest Family,

Thank you for the lovely send off. I do wish you were all on board with me and

could come and dance with me at my wedding. We are having a very comfortable

voyage. There were only four of the passengers as far as Durban, all of them women,

but I believe we are taking on more here. I have a most comfortable deck cabin to

myself and the use of a sumptuous bathroom. No one is interested in deck games and I

am having a lazy time, just sunbathing and reading.I sit at the Captain’s table and the meals are delicious – beautifully served. The

butter for instance, is moulded into sprays of roses, most exquisitely done, and as for

the ice-cream, I’ve never tasted anything like them.The meals are continental type and we have hors d’oeuvre in a great variety

served on large round trays. The Italians souse theirs with oil, Ugh! We also of course

get lots of spaghetti which I have some difficulty in eating. However this presents no

problem to the Chief Engineer who sits opposite to me. He simply rolls it around his

fork and somehow the spaghetti flows effortlessly from fork to mouth exactly like an

ascending escalator. Wine is served at lunch and dinner – very mild and pleasant stuff.

Of the women passengers the one i liked best was a young German widow

from South west Africa who left the ship at East London to marry a man she had never

met. She told me he owned a drapers shop and she was very happy at the prospect

of starting a new life, as her previous marriage had ended tragically with the death of her

husband and only child in an accident.I was most interested to see the bridegroom and stood at the rail beside the gay

young widow when we docked at East London. I picked him out, without any difficulty,

from the small group on the quay. He was a tall thin man in a smart grey suit and with a

grey hat perched primly on his head. You can always tell from hats can’t you? I wasn’t

surprised to see, when this German raised his head, that he looked just like the Kaiser’s

“Little Willie”. Long thin nose and cold grey eyes and no smile of welcome on his tight

mouth for the cheery little body beside me. I quite expected him to jerk his thumb and

stalk off, expecting her to trot at his heel.However she went off blithely enough. Next day before the ship sailed, she

was back and I saw her talking to the Captain. She began to cry and soon after the

Captain patted her on the shoulder and escorted her to the gangway. Later the Captain

told me that the girl had come to ask him to allow her to work her passage back to

Germany where she had some relations. She had married the man the day before but

she disliked him because he had deceived her by pretending that he owned a shop

whereas he was only a window dresser. Bad show for both.The Captain and the Chief Engineer are the only officers who mix socially with

the passengers. The captain seems rather a melancholy type with, I should say, no

sense of humour. He speaks fair English with an American accent. He tells me that he

was on the San Francisco run during Prohibition years in America and saw many Film

Stars chiefly “under the influence” as they used to flock on board to drink. The Chief

Engineer is big and fat and cheerful. His English is anything but fluent but he makes up

for it in mime.I visited the relations and friends at Port Elizabeth and East London, and here at

Durban. I stayed with the Trotters and Swans and enjoyed myself very much at both

places. I have collected numerous wedding presents, china and cutlery, coffee

percolator and ornaments, and where I shall pack all these things I don’t know. Everyone has been terribly kind and I feel extremely well and happy.At the start of the voyage I had a bit of bad luck. You will remember that a

perfectly foul South Easter was blowing. Some men were busy working on a deck

engine and I stopped to watch and a tiny fragment of steel blew into my eye. There is

no doctor on board so the stewardess put some oil into the eye and bandaged it up.

The eye grew more and more painful and inflamed and when when we reached Port

Elizabeth the Captain asked the Port Doctor to look at it. The Doctor said it was a job for

an eye specialist and telephoned from the ship to make an appointment. Luckily for me,

Vincent Tofts turned up at the ship just then and took me off to the specialist and waited

whilst he extracted the fragment with a giant magnet. The specialist said that I was very

lucky as the thing just missed the pupil of my eye so my sight will not be affected. I was

temporarily blinded by the Belladona the eye-man put in my eye so he fitted me with a

pair of black goggles and Vincent escorted me back to the ship. Don’t worry the eye is

now as good as ever and George will not have to take a one-eyed bride for better or

worse.I have one worry and that is that the ship is going to be very much overdue by

the time we reach Dar es Salaam. She is taking on a big wool cargo and we were held

up for three days in East london and have been here in Durban for five days.

Today is the ninth Anniversary of the Fascist Movement and the ship was

dressed with bunting and flags. I must now go and dress for the gala dinner.Bless you all,

Eleanor.S.S.Timavo. 6th. November 1930

Dearest Family,

Nearly there now. We called in at Lourenco Marques, Beira, Mozambique and

Port Amelia. I was the only one of the original passengers left after Durban but there we

took on a Mrs Croxford and her mother and two men passengers. Mrs C must have

something, certainly not looks. She has a flat figure, heavily mascared eyes and crooked

mouth thickly coated with lipstick. But her rather sweet old mother-black-pearls-type tells

me they are worn out travelling around the world trying to shake off an admirer who

pursues Mrs C everywhere.The one male passenger is very quiet and pleasant. The old lady tells me that he

has recently lost his wife. The other passenger is a horribly bumptious type.

I had my hair beautifully shingled at Lourenco Marques, but what an experience it

was. Before we docked I asked the Captain whether he knew of a hairdresser, but he

said he did not and would have to ask the agent when he came aboard. The agent was

a very suave Asian. He said “Sure he did” and offered to take me in his car. I rather

doubtfully agreed — such a swarthy gentleman — and was driven, not to a hairdressing

establishment, but to his office. Then he spoke to someone on the telephone and in no

time at all a most dago-y type arrived carrying a little black bag. He was all patent

leather, hair, and flashing smile, and greeted me like an old and valued friend.

Before I had collected my scattered wits tthe Agent had flung open a door and

ushered me through, and I found myself seated before an ornate mirror in what was only

too obviously a bedroom. It was a bedroom with a difference though. The unmade bed

had no legs but hung from the ceiling on brass chains.The agent beamingly shut the door behind him and I was left with my imagination

and the afore mentioned oily hairdresser. He however was very business like. Before I

could say knife he had shingled my hair with a cut throat razor and then, before I could

protest, had smothered my neck in stinking pink powder applied with an enormous and

filthy swansdown powder puff. He held up a mirror for me to admire his handiwork but I

was aware only of the enormous bed reflected in it, and hurriedly murmuring “very nice,

very nice” I made my escape to the outer office where, to my relief, I found the Chief

Engineer who escorted me back to the ship.In the afternoon Mrs Coxford and the old lady and I hired a taxi and went to the

Polana Hotel for tea. Very swish but I like our Cape Peninsula beaches better.

At Lorenco Marques we took on more passengers. The Governor of

Portuguese Nyasaland and his wife and baby son. He was a large middle aged man,

very friendly and unassuming and spoke perfect English. His wife was German and

exquisite, as fragile looking and with the delicate colouring of a Dresden figurine. She

looked about 18 but she told me she was 28 and showed me photographs of two

other sons – hefty youngsters, whom she had left behind in Portugal and was missing

very much.It was frightfully hot at Beira and as I had no money left I did not go up to the

town, but Mrs Croxford and I spent a pleasant hour on the beach under the Casurina

trees.The Governor and his wife left the ship at Mozambique. He looked very

imposing in his starched uniform and she more Dresden Sheperdish than ever in a

flowered frock. There was a guard of honour and all the trimmings. They bade me a warm farewell and invited George and me to stay at any time.The German ship “Watussi” was anchored in the Bay and I decided to visit her

and try and have my hair washed and set. I had no sooner stepped on board when a

lady came up to me and said “Surely you are Beeba Leslie.” It was Mrs Egan and she

had Molly with her. Considering Mrs Egan had not seen me since I was five I think it was

jolly clever of her to recognise me. Molly is charming and was most friendly. She fixed

things with the hairdresser and sat with me until the job was done. Afterwards I had tea

with them.Port Amelia was our last stop. In fact the only person to go ashore was Mr

Taylor, the unpleasant man, and he returned at sunset very drunk indeed.

We reached Port Amelia on the 3rd – my birthday. The boat had anchored by

the time I was dressed and when I went on deck I saw several row boats cluttered

around the gangway and in them were natives with cages of wild birds for sale. Such tiny

crowded cages. I was furious, you know me. I bought three cages, carried them out on

to the open deck and released the birds. I expected them to fly to the land but they flew

straight up into the rigging.The quiet male passenger wandered up and asked me what I was doing. I said

“I’m giving myself a birthday treat, I hate to see caged birds.” So next thing there he

was buying birds which he presented to me with “Happy Birthday.” I gladly set those

birds free too and they joined the others in the rigging.Then a grinning steward came up with three more cages. “For the lady with

compliments of the Captain.” They lost no time in joining their friends.

It had given me so much pleasure to free the birds that I was only a little

discouraged when the quiet man said thoughtfully “This should encourage those bird

catchers you know, they are sold out. When evening came and we were due to sail I

was sure those birds would fly home, but no, they are still there and they will probably

remain until we dock at Dar es Salaam.During the morning the Captain came up and asked me what my Christian name

is. He looked as grave as ever and I couldn’t think why it should interest him but said “the

name is Eleanor.” That night at dinner there was a large iced cake in the centre of the

table with “HELENA” in a delicate wreath of pink icing roses on the top. We had

champagne and everyone congratulated me and wished me good luck in my marriage.

A very nice gesture don’t you think. The unpleasant character had not put in an